BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

They sued Boston’s public schools for better education for Black children. Instead, they got busing.

Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. delivered a verdict in the plaintiffs’ favor. But it wasn’t a victory.

Earline Pruitt was still blocks away from Hyde Park High School when the screaming started.

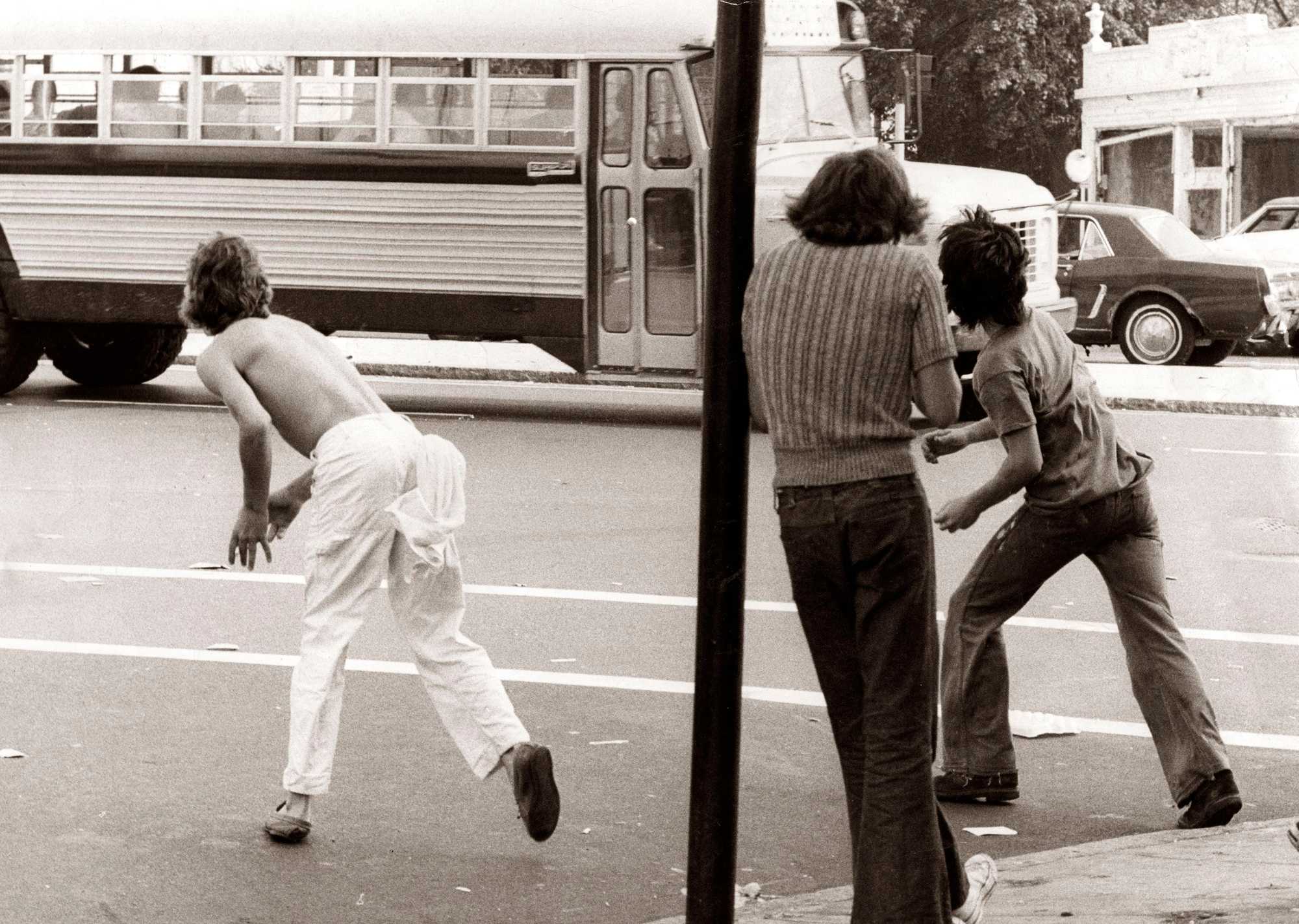

Hordes of parents, grandparents, and neighbors mobbed both sides of Metropolitan Avenue early on the first day of school, a corridor of hatred seemingly without end.

She was less than four miles from her house in Dorchester, but as she watched residents yelling racial slurs and spitting on her children’s school bus, she felt far from home. Gripping the steering wheel of her station wagon, she trailed slowly behind the caravan of buses and law enforcement escorts, struggling to keep her children’s bus in sight until a police blockade forced her to turn back.

At home, she attempted to quiet her fury and fear, pushing away the thoughts of the nightmare her children had just experienced. But as she tried to do her usual chores around the house, her fists clenched tight as if they were still squeezing the wheel. The weight of countless “what-ifs” was unbearable.

Finally, she took a seat at the kitchen table and prayed fiercely for her children’s safety. Then her mind filled with renewed resolve. This was not what she wanted, but there was no going back.

“It’s never what I wanted for them,” she said. “I wanted them to be able to just walk up the street and go to school and get the education [white kids] were getting out there.”

She was like so many Black parents living through their first traumatic day of court-ordered desegregation. But unlike theirs, her feelings were mingled with a very personal guilt: She was a plaintiff in the historic busing case, Morgan v. Hennigan, one of the 14 parents who helped win the 1974 federal desegregation order.

In their quest for better neighborhood schools for Black children, Pruitt and 13 other families, including 43 children, inadvertently landed at the center of one of the most contentious civil rights battles in Boston’s history. Busing would leave its mark on the city, changing its demographics as many families fled the city after the decision, and creating a national reputation that, to this day, leads many outside observers to see Boston as an unsafe place for people of color.

For Pruitt and other parents involved in the lawsuit the question struck closer to home: Was Boston safe for their children? Would hope survive? Would they?

Advertisement

In the 1970s, Pruitt was a single mother of eight who considered a good education a necessity, the gateway to a lifetime of opportunity. She took after her own mother, a disciplinarian who expected nothing below a B on her children’s report cards.

In high school in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Pruitt attended Boston’s prestigious Girls Latin, then on Huntington Avenue in the Fenway, a public school that admitted only students who scored high enough on the entrance exam. (Then, Boston Latin was the exam school for boys. Girls Latin evolved into today’s Latin Academy.)

She remembers enjoying those years, sticking close to one of her best friends from her neighborhood in Roxbury as she navigated the predominantly white school. She believed the city owed the same quality education that she received at Girls Latin to all its children.

Tired of the dingy hand-me-down books and of teachers who failed to give students the attention they deserved, she wanted her children to have the same updated coursework, clean classrooms, and modern equipment afforded to white students. The differences between Black and white high schools became even more noticeable as Pruitt’s three eldest daughters enrolled in Metco, a voluntary integration program launched in 1966 that bused Black students to some of the finest high schools in the state in communities such as Sudbury, Marblehead, and Newton.

“The quality of the work was more intense, more elevated, just greater,” said Pruitt, 90, in a recent interview in her Dorchester home. “And I wanted that for all my children, without having to get on a bus.”

The concern that Black students were being shortchanged was well founded: Schools in some Black neighborhoods in the 1950s were funded at a fraction of school funding in white neighborhoods. In the 1960s, a Harvard report found that two-thirds of Black schools were in poor condition and should be closed immediately.

Year after year, the efforts of Black parents were thwarted by the all-white School Committee and other school administrators, who refused to offer any meaningful investment in predominantly Black schools while systematically preventing Black students from entering majority-white schools. The persistent defense of these unlawful inequities made the committee and its chair, James Hennigan, the primary target for the civil rights lawsuit.

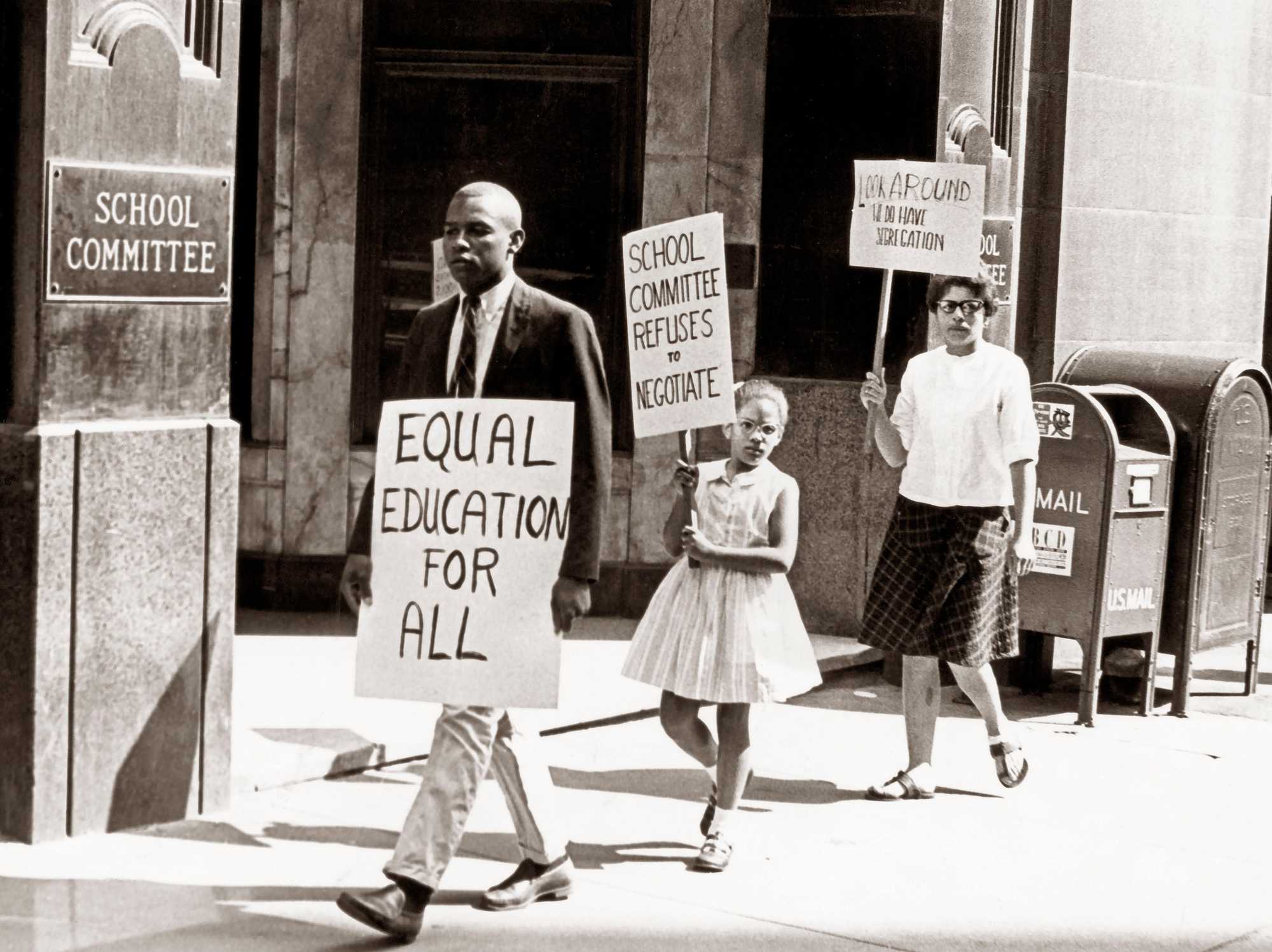

For a decade before federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled in the case, parents had marched, protested, and rallied, desperate to improve the conditions of Black schools in the city. Some dutifully attended School Committee meetings where they were either taunted or ignored altogether, while others participated in daylong boycotts of BPS, sending their children to unofficial “Freedom Schools” hosted by Black community organizations around Dorchester and Roxbury.

By 1972, Black families were ready to try a new tactic. The Boston NAACP and two Dorchester nonprofits looked for families to sign onto a lawsuit that would demand a school system “free of racial discrimination, segregation, and unequal educational opportunity.”

Advertisement

The NAACP, in partnership with Freedom House and the Dorchester Council for Community Schools, spread the word to friends and family, looking for families with children old enough to be in public school who had experienced, or risked experiencing, racial discrimination in the district.

Pruitt learned of the complaint through her older sister Salena, who worked the front desk at the Freedom House in the 1970s. When she learned that civil rights attorneys were looking to file a discrimination lawsuit against the Boston School Committee, she was eager to sign onto what seemed like a promising opportunity to make real change on behalf of her children.

Other families desperate to make public education better for Black children also joined in, each with reasons and experiences of their own.

Diane Bassett, who learned about the lawsuit from her then-brother-in-law, imagined the judge ordering a total overhaul of the district. She was incensed about the reports she heard of schools where children were shuffled from grade to grade, even as they struggled to master basic reading skills.

“They didn’t care if you were educated, they just wanted you to move through the system,” she said. “I didn’t want that to happen to my children.”

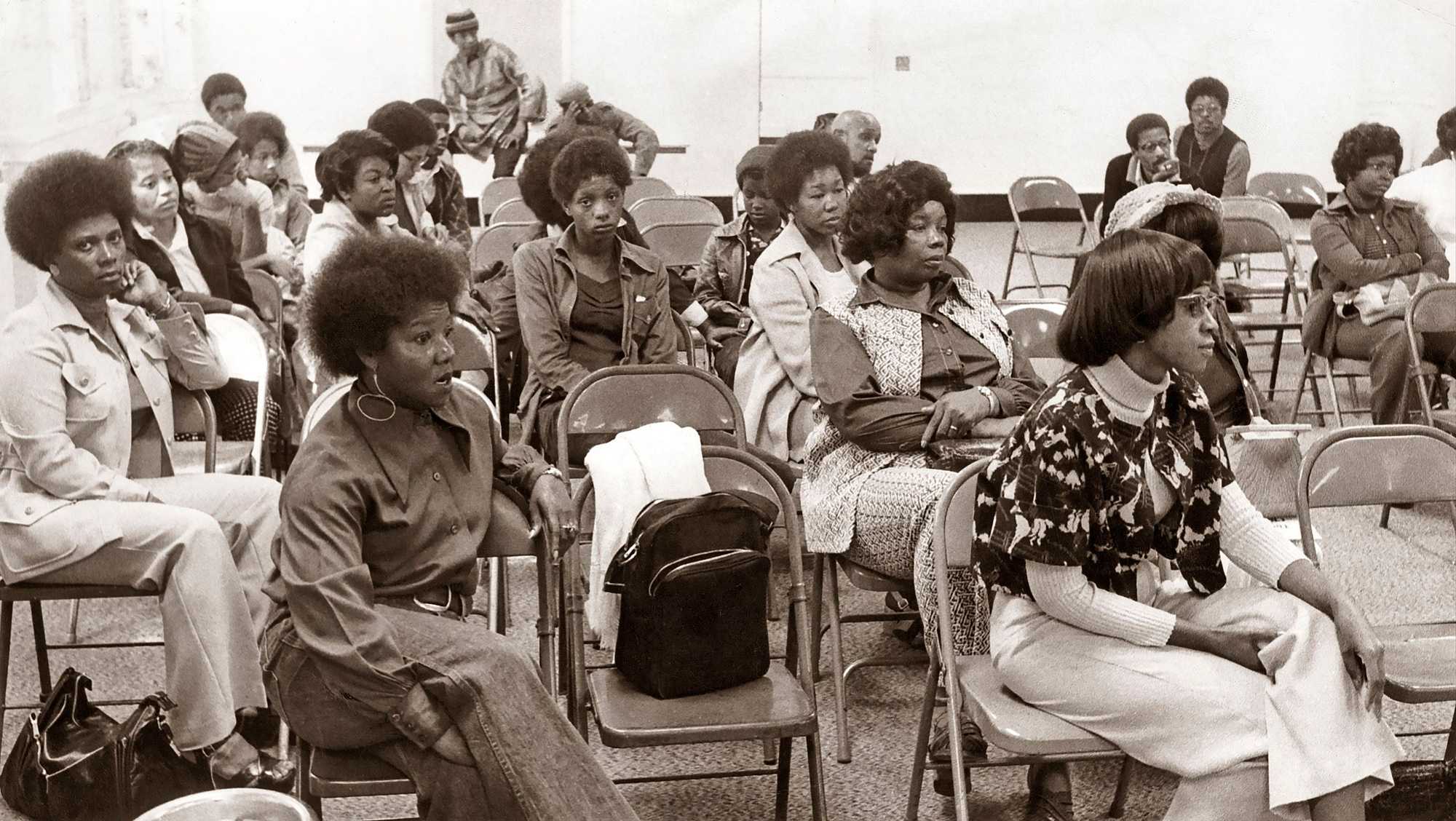

Bassett dreamed of public schools in Roxbury with new books and clean classrooms that rivaled Berea Academy, the private school then located by Franklin Park where she could afford to send only the two oldest of her five children. Determined to find ways to improve the public schools her toddlers would soon be expected to attend, she dutifully attended School Committee meetings. If school leaders wouldn’t respond to activism, she thought, perhaps legal action would work.

Lorraine Johnson-Graham, another plaintiff, saw joining the lawsuit as part of her civic duty.

“It’s just like voting,” she said. “You have to fight for those that don’t have people to fight for them ... for equity and justice.”

Growing up, Johnson-Graham endured racist treatment during her own years at BPS. She spent many of her early years in predominantly white schools where she was made to feel less-than because of her skin color. As a lighter-skinned Black girl, Johnson-Graham remembers one of her white peers saying that her skin “wasn’t too bad.”

“It was like ... ‘You look almost like us,’” but not quite enough, she said.

At 16, she dropped out of high school, feeling that BPS had failed her. But raising her own three children, she believed it was possible to change the system.

And then there was Tallulah Morgan, the lead plaintiff in the case. Morgan, who died in 2020, also attended BPS schools after moving to Boston from Georgia, and graduated from Jeremiah Burke High School. Morgan’s children declined to speak to the Globe for this story, but other plaintiffs remembered her as among the most spirited and determined of the group.

When the plaintiff group was set, they gathered periodically at the Freedom House to give depositions to attorneys. Parents described dilapidated buildings with peeling paint, Black children crowded three or four to a desk, and classrooms where students received passing grades on quizzes when the only correct answer on the page was their name.

And yet, as the case plodded along over the next two years, a seed of doubt began to take root among many of the families.

“I don’t know [if I was] so much excited as skeptical: not believing it was going to really happen, but hopeful that it might,” Pruitt recalled. “How else can I put it? I still had that little something bothering me, that this isn’t going to be what you want. And it wasn’t.”

Advertisement

Pruitt was huddled with her children around the living room television watching the nightly news when word of the decision in the court case finally came down.

On June 21, 1974, Judge Garrity resolved Morgan v. Hennigan by ordering that students be bused to schools outside of their neighborhoods to reach racial parity and end de facto segregation and racial discrimination in the school system.

Pruitt was disappointed. The plan — to bus white students into predominantly Black schools, and Black students into predominantly white ones — contained no mention of improved curriculum, not a word about new textbooks or smaller class sizes or more experienced teachers. Nothing to suggest that her younger children would receive their choice of honors classes, in an environment that would both challenge and encourage. The future the plaintiffs had yearned for, a guarantee of high-quality education, had once again eluded Black families in Boston.

But the judge had made his decision. Now the original plaintiffs, like every other parent of a school-age child in Boston, had their own decisions to make. Would they stay and participate in Garrity’s experiment? Or pull their kids out of Boston, in favor of a school district where a good education was a promise, not a dream?

Of the plaintiff families, at least three of the 14 ultimately left Boston, the city they had hoped to change.

Bassett and her husband were among them, packing up the family and moving to Middleborough the year after the decision.

Of the plaintiff families, at least three of the 14 ultimately left Boston, the city they had hoped to change.

Like many other parents, Johnson-Graham stayed living in Boston, but soon pulled her children out of BPS and enrolled them in Metco. After so many painful years fighting for their rights, she didn’t feel safe sending her sons to Boston schools.

Pruitt and a few others, however, committed to facing whatever uncertain future lay ahead at Boston Public Schools. Pruitt had no idea what she might be sacrificing, but she held tight to a fragment of hope that busing could be a good thing for her four younger children and the community.

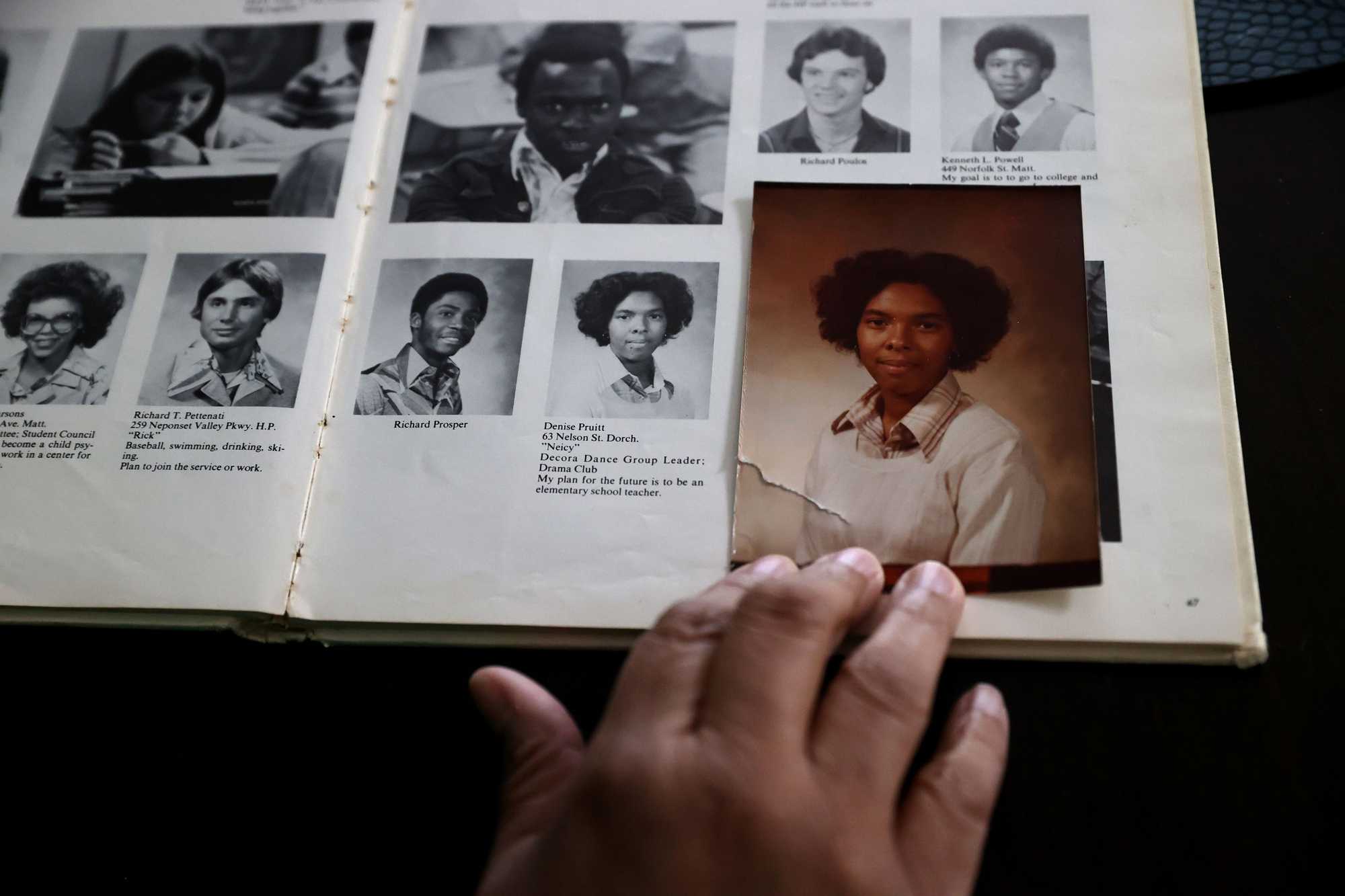

Garrity’s plan rolled out in phases. In the first year of court-ordered busing, Pruitt’s two middle children, Denise and James, remained at their neighborhood schools. She found out the following year, however, that the two were assigned to start at Hyde Park High School in September 1975.

She knew little about the neighborhood except that it was residential, quiet, and populated with middle-class families. She imagined it not too different from her own, a tight-knit corner of Dorchester where residents looked out for one another.

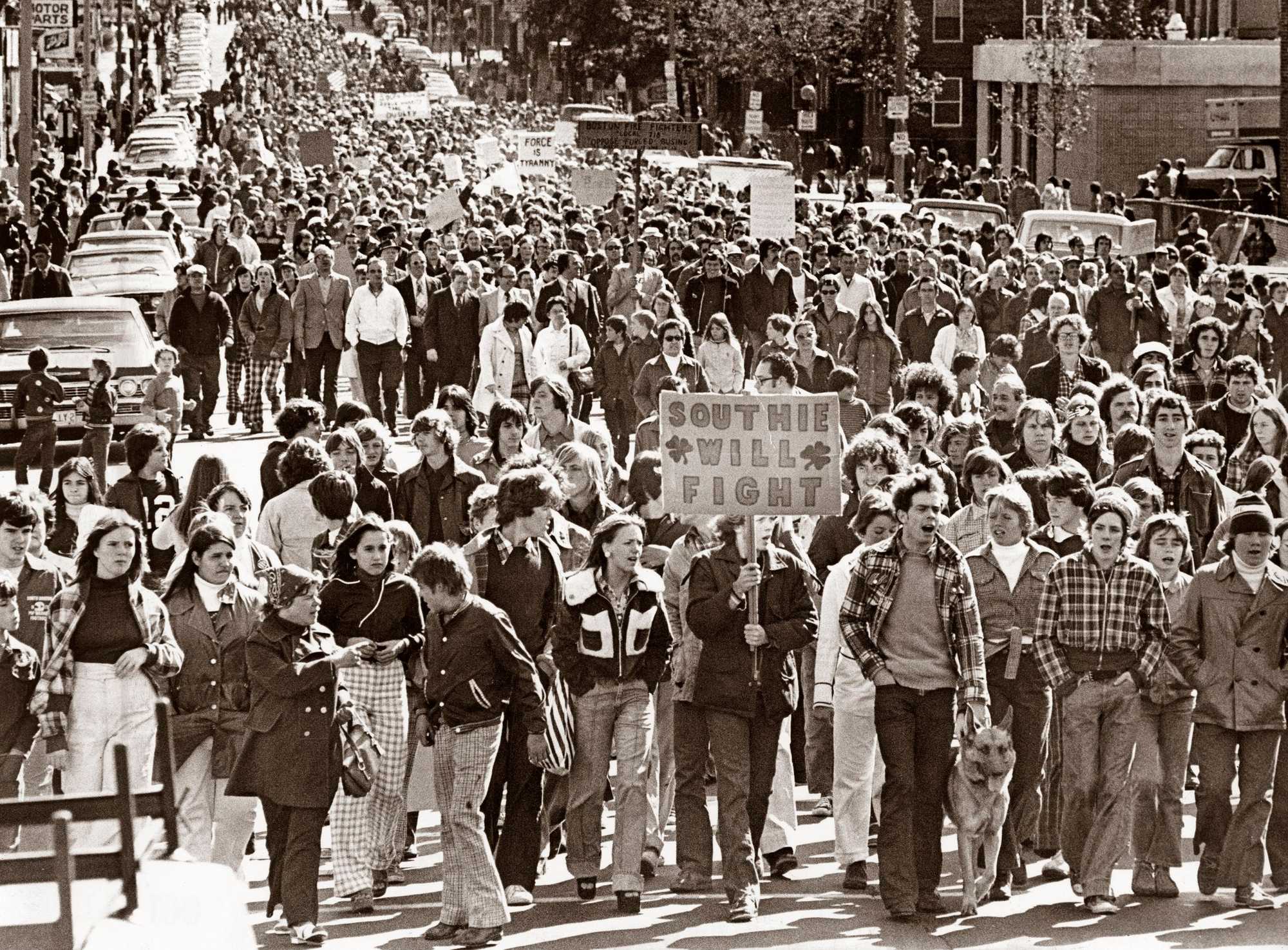

As the first day of school drew nearer, Pruitt drove Denise and James to the high school. The brick building seemed magnificent with its wrought-iron fence and sprawling lawn. This wasn’t going to be like the integration of South Boston High School the year before, where antibusing protests continuously roiled the neighborhood, where angry white people dared Garrity to take back his decision and hoisted signs emblazoned with “WHITES HAVE RIGHTS.”

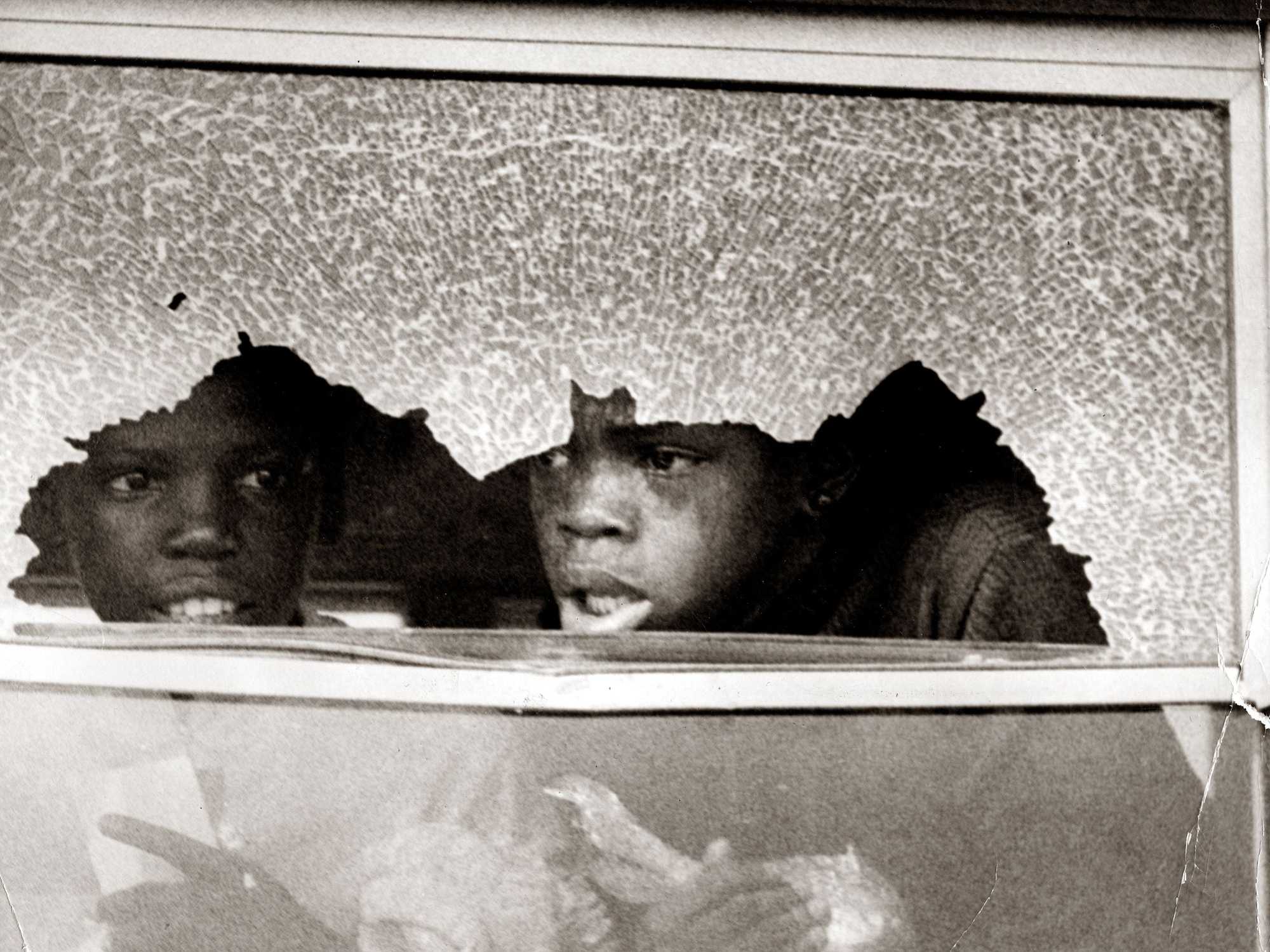

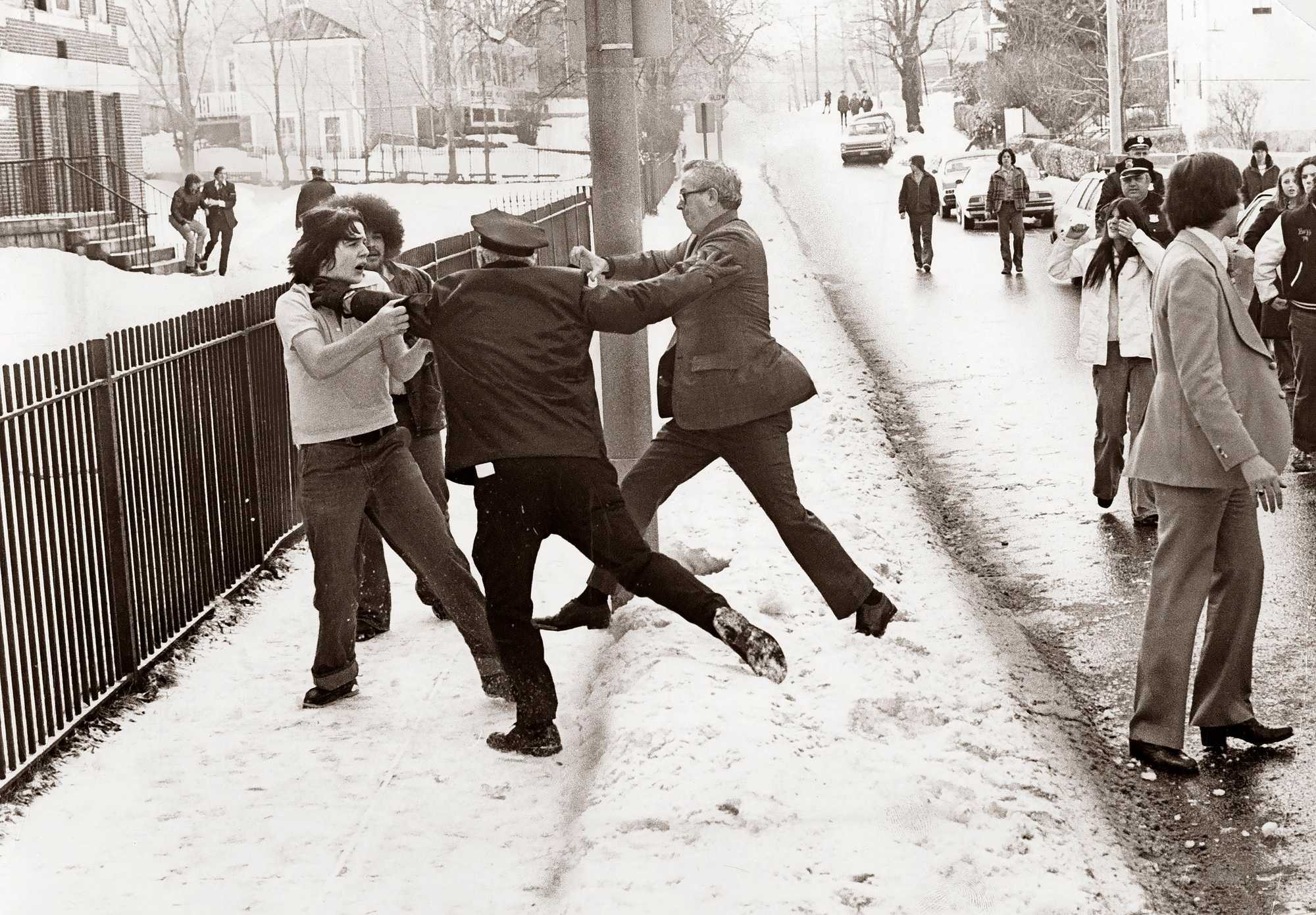

At left, protesters participated in an antibusing march in South Boston on Oct. 4, 1974. Two Boston students looked out of a broken school bus window on Sept. 12, 1974. (Ted Dully/ Globe Staff, Boston Globe File)

She took the kids to buy new first-day-of school outfits. The usual restrictions of price and style were replaced by words rarely spoken in the Pruitt household: Get anything you want. She just wanted her babies to feel about themselves the way she saw them: confident and beautiful. For James, this meant a sharp pair of slacks with a shirt to match, and for Denise, a brown skirt and crepe blouse with vines creeping over every fold of fabric.

By the first day of school, Pruitt had managed to channel some of her daughter’s excitement about starting high school — Her own locker! A cafeteria! — as she waved goodbye at the bus stop, flanked by a cluster of news cameras and police officers.

She longed to get on the bus with them, to personally escort them inside the unfamiliar school. But the best she could do was rush home, hop in her station wagon, and follow behind the convoy of buses out of Dorchester and into the chaos ahead.

In the months and years that followed, Pruitt gathered her children around the dinner table after school to talk about their days. Once, Pruitt’s daughter described a protester who broke through the barricade of police officers and lunged at a group of Black students, his eyes wild with rage. Another day, Pruitt learned someone had thrown a giant trash barrel into the air, sending debris sailing over her daughter’s head as she tried to hurry onto the school bus.

Pruitt sought to protect her children however she could, taking a job as a reading program aide at the high school a few months into her daughter’s freshman year. It brought a small sense of relief to be mere feet from her children. But it also brought fresh challenges, as she experienced firsthand the trauma her teenagers faced each day.

Depending on where you walked throughout the building, the muted roar of demonstrators outside swelled and faded, a steady din for weeks on end. On at least one occasion, fights between Black and white students forced the school to end class early.

She encouraged her children to be strong, invoked images of Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and Ruby Bridges, and reminded them they could do anything they set their minds to, no matter what anyone said.

Students and school buses lined up outside of Hyde Park High School in Boston following a campus evacuation due to a bomb threat on April 29, 1976. (Ed Jenner/Globe Staff)

Privately, the stress chipped away at her. Every new horror story, every awful anecdote sent her blood pressure skyrocketing. It was almost too much to bear, so many individual pinpricks of pain year after year.

So it seemed a rare moment of hope when a thick envelope from Wheelock College arrived in the mail for Denise one day in the spring of her senior year.

She was proud that her daughter’s top choice was also her alma mater. Only a few years earlier, Pruitt graduated from Wheelock with a degree in early childhood education, the victorious end to countless evenings spent at the kitchen table, doing homework elbow to elbow with her children.

Denise was eager to tear open the letter right away, but Pruitt insisted her daughter wait until her grandparents arrived in town a few days later, so they could celebrate the good news together.

The big day came quickly, and Pruitt gathered the family around the dining table to watch Denise open the envelope, peering eagerly at its contents as her daughter yanked out the papers inside.

Suddenly, Denise’s face fell.

Rejected.

Thank you for applying, the letter said, in effect. You’re a great student, and you would do well here in the future. Please consider a two-year school and apply to us again in two years.

“I was crushed,” Denise Pruitt said in a recent interview. “It was heart-wrenching because I really thought I had gotten in ... [but] they just did not think I would be successful at their institution.”

Her mother called the school to demand an immediate meeting with the admissions office. Pruitt had invested everything, sacrificed everything, to ensure her daughter could receive a college education. When she stormed into the office, she resolved that she would not leave without an explanation.

The one she received shocked her.

The constant turmoil around desegregation had given schools like South Boston and Hyde Park a reputation. In the newspapers, her daughter’s school was painted as “a scene of tension” plagued by “scattered fighting,” and colleges couldn’t be sure that students were really learning amid such a disruptive environment. Denise was welcome to apply again as a transfer student in two years, the school officials told her, but would not be accepted as a freshman.

Recognizing Denise’s grades were excellent, and her SAT scores were among the best in her grade, Pruitt couldn’t help but wonder, Would life have been different if she’d made different choices for her children?

“She could have gone to any school she wanted to go to,” she said ruefully.

Advertisement

The rejection from Wheelock, followed by similar rejections from Simmons and Emmanuel, bruised Denise. But Pruitt was determined that her daughter stay the course, and so together, they decided that Denise would go to Salem State. Her brother, James, was there, as was her older sister Betty, who had graduated from Marblehead High a few years earlier.

Today, Pruitt beams recalling how her daughter excelled at college, earned both master’s and doctoral degrees, and went on to become a professor at both Mass Bay Community College and Tufts University. Her son James, meanwhile, became a skilled artist and craftsman. Many of the other child plaintiffs have become business owners, teachers, researchers, and computer scientists. Each, in their own way, has passed on the value of education to their families.

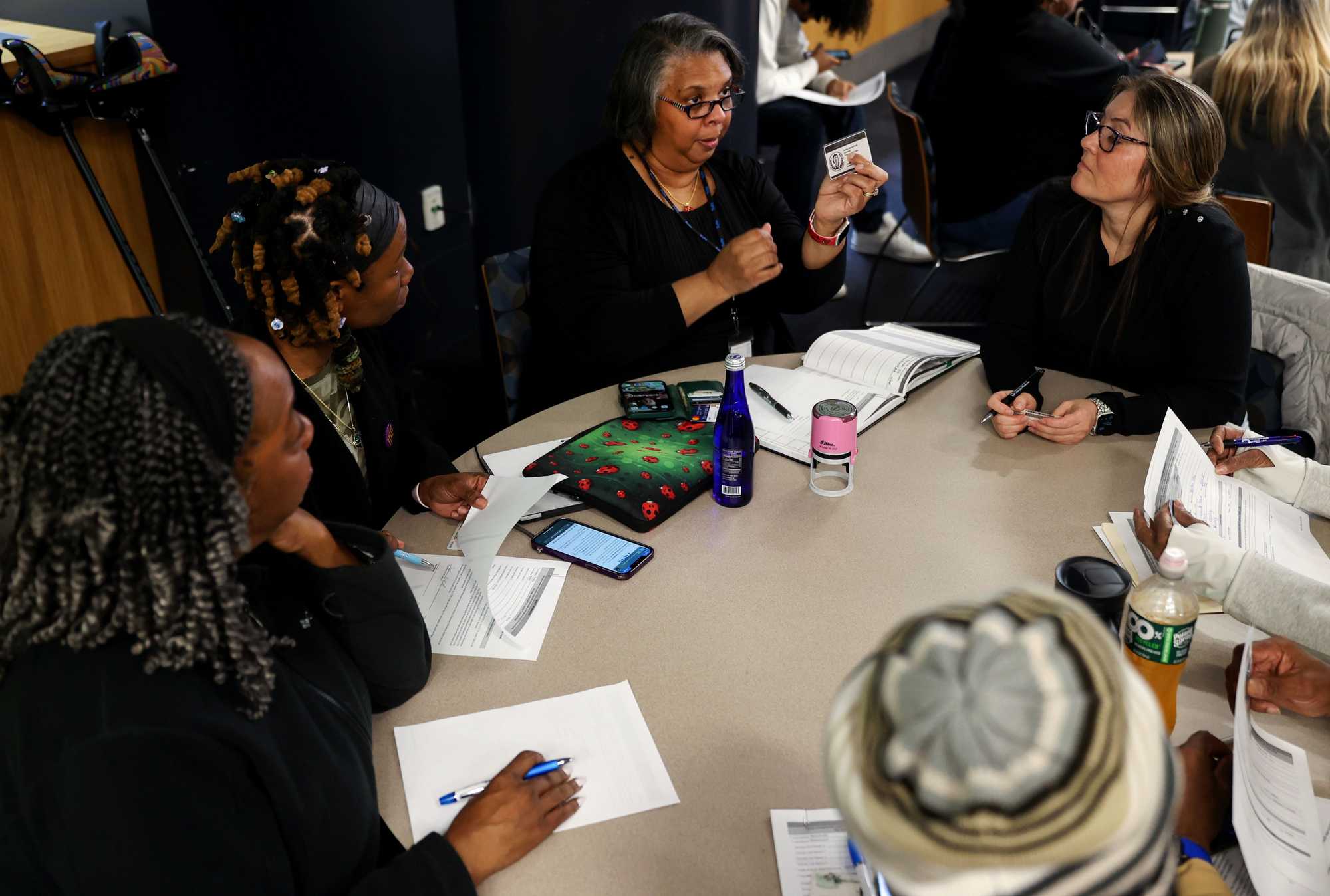

At left, Denise Garrow-Pruitt is a part-time instructor at Tufts Medical School in Boston and a professor at MassBay Community College. Earline Pruitt enjoyed a laugh on her 90th birthday at home with her daughter Betty Weeks, at right. (Jonathan Wiggs/Globe Staff)

Pruitt was proud and grateful that her daughter did not crumple beneath the weight of busing. But she was also pleased Denise chose to raise her own family in Brookline, and that most of her other children had chosen similarly well-resourced suburbs.

When she looks outside her front window onto Maxwell Street, Pruitt can still see the site of the old Frank V. Thompson Middle School, closed two decades ago in no better condition than when her own children went there. In its final years, the student body was more than 75 percent Black, and nearly half the eighth grade received “warning” or “failing” grades in math and science. For the schools in her neighborhood, busing didn’t change much.

“They thought it was going to help, and you see how much it helped,” Pruitt said. “Zero.”

Other plaintiffs have also wrestled with the rippling effects of their decision to sue, and on the legacy of busing in Boston.

Watching desegregation play out as a school counselor in the 1970s, Lorraine Johnson-Graham couldn’t help but feel that Black children were on the front lines of a conflict they’d never asked to be part of, “a battle that wasn’t really theirs.”

It’s a battle, Johnson-Graham contends, that intensified with each passing year and still shapes the city today.

“I felt I was like a little stone in a big big pond,” she reflected recently. “But ... it gave me a sense of purpose, to be a part of trying to make change.”

In Pruitt’s mind, busing was a story of sacrifice, of overcoming, but it was not a story of victory. Reflecting on the aftermath of the ruling, she tries not to feel bitter, and reminds herself of all she didn’t know — couldn’t have known — at the time.

“This isn’t what I’d hoped,” she said, “but I did [try] something to help people, and that makes me feel proud of myself, just a little.”

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC