BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

With new busing curriculum, BPS tackles its own history. But will all students get a chance to learn?

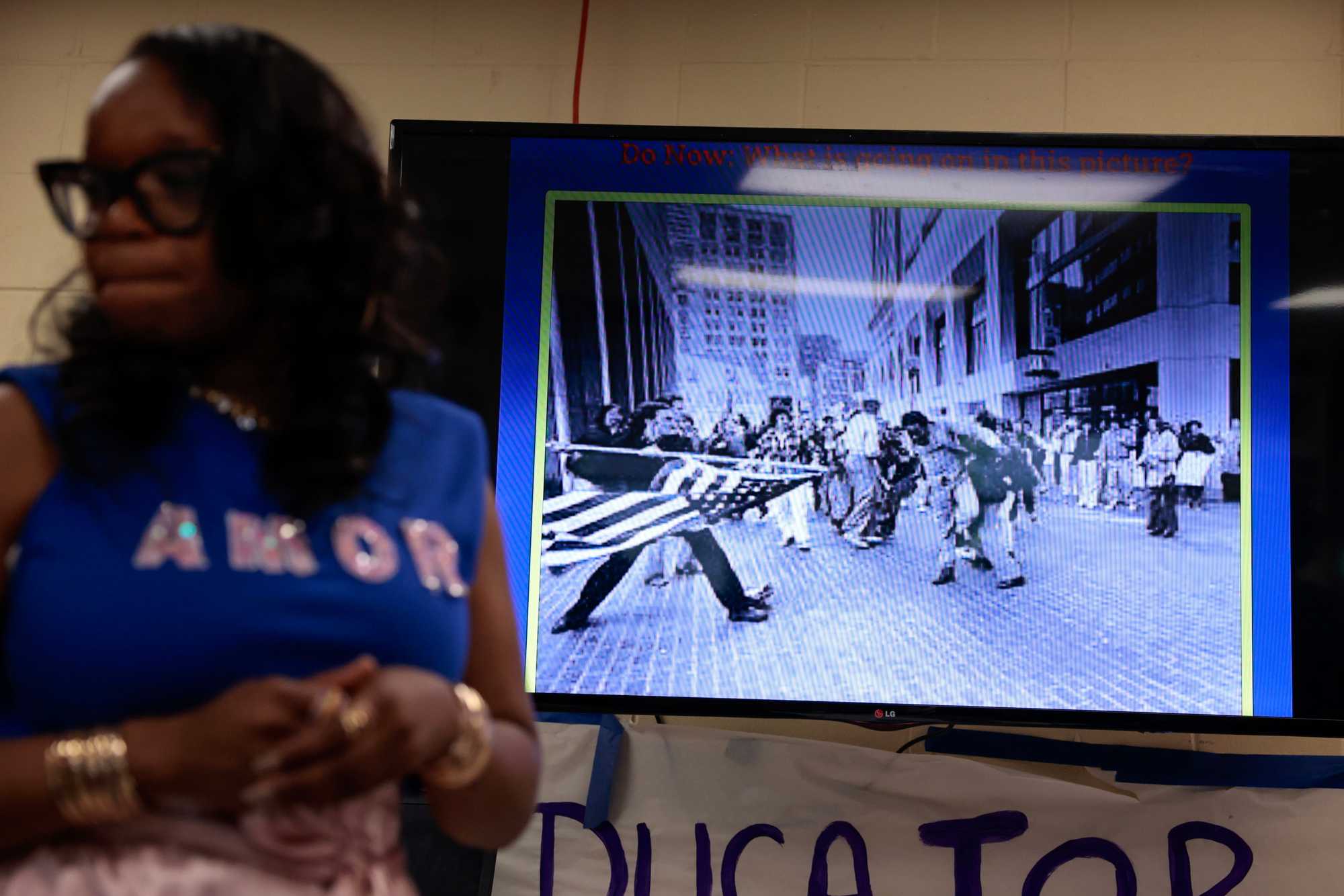

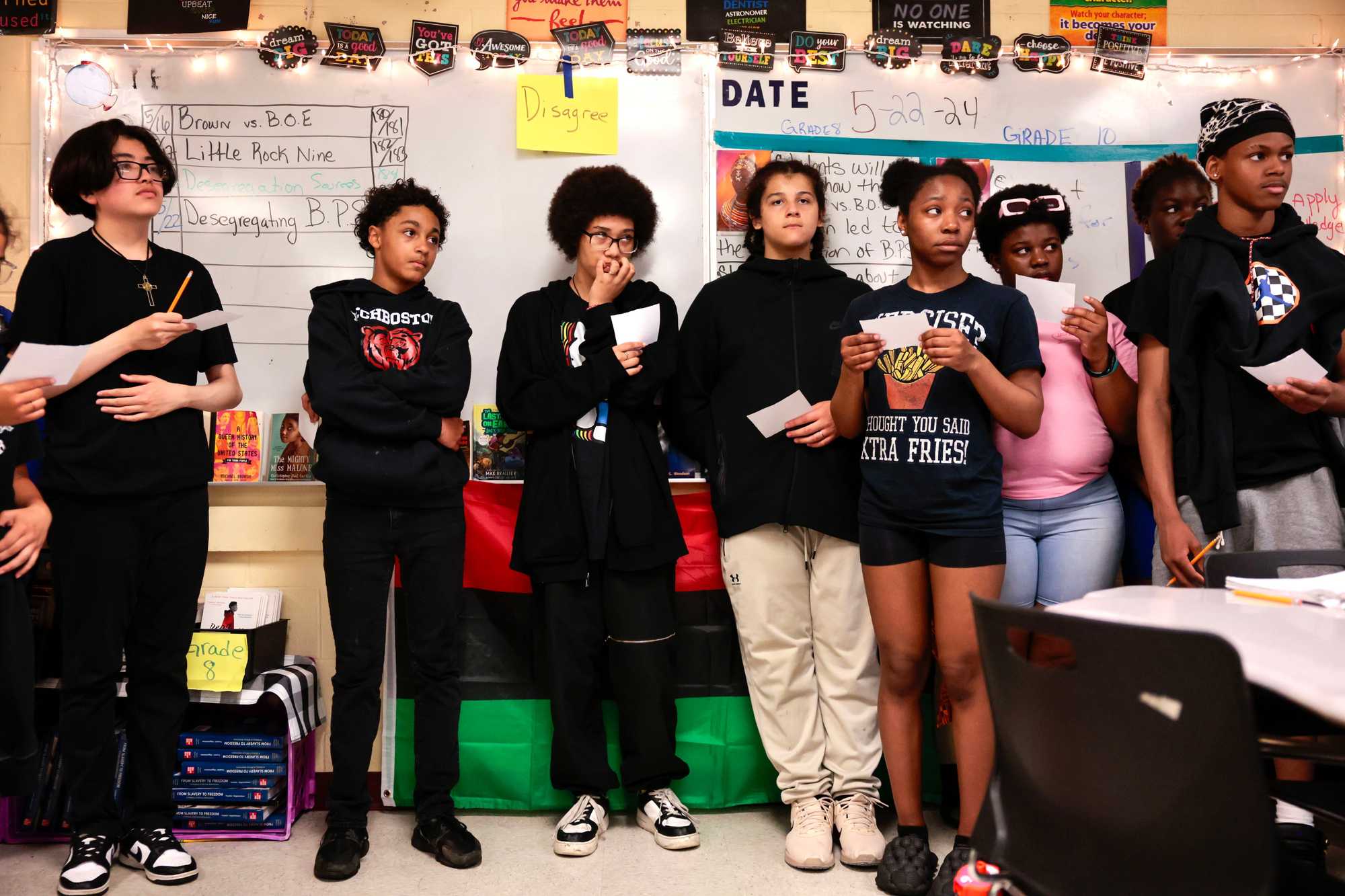

It wasn’t the obvious brutality, or even the unrestrained racism, of the old black-and-white photo that left the students in Tanisha Milton’s eighth grade civics class aghast. Sitting in their classroom at Dorchester’s TechBoston Academy one day this spring, it was how close the photo hit to home.

“Does anybody want to infer where they think this is at?” Milton queried, pointing to the infamous 1976 photo of a white teen nearly impaling Black attorney Ted Landsmark with a flagpole bearing the American flag. Landsmark had just rounded the corner of the plaza on his way to a meeting, when he happened upon a mob of white antibusing protestors.

“This is downtown — City Hall, Government Center,” Milton explained.

“Ohh!” several students exclaimed in unison. Others were stunned silent, slack-jawed.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning photo served as an entry point for an hourlong lesson on the desegregation of Boston Public Schools, an era pivotal to understanding the city’s past, present, and, arguably, its future. However, Milton’s lesson, which she voluntarily designed, has been the exception, not the norm.

Advertisement

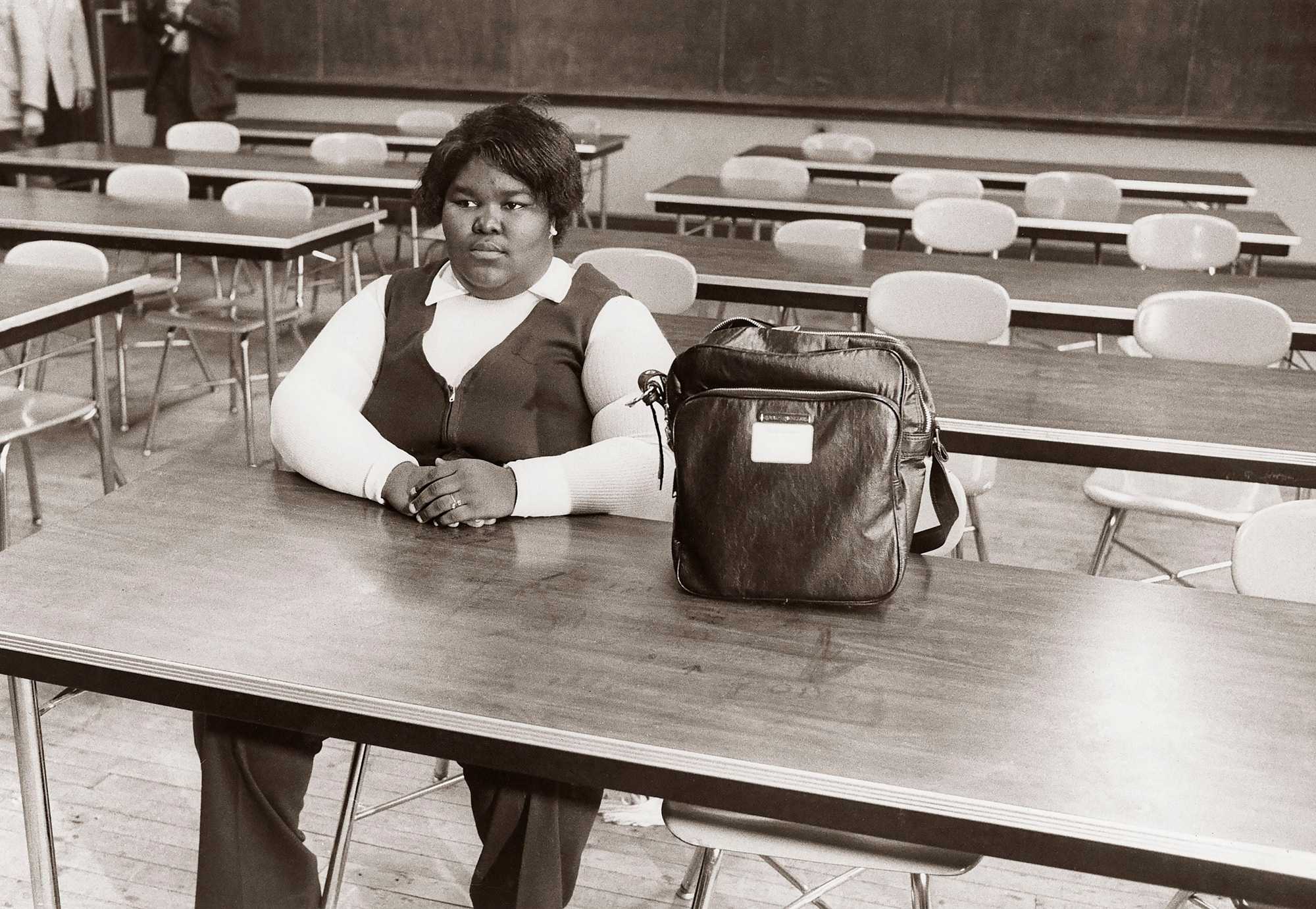

For decades, BPS teachers, who have long prized their autonomy in crafting lessons, have been reticent to teach students about the tumult that followed the 1974 federal busing order, preferring instead to focus coursework on Southern integration battles. While Boston’s busing struggle has been a state-recommended topic in high school since 2018, it’s not being taught to all BPS high schoolers. Some students say they have never been exposed to Boston’s history of busing and desegregation in their classrooms.

“I haven’t heard anything about it,” said Simone Frederick, who graduated this month from Boston Latin Academy, one of the city’s most academically demanding high schools.

Milton created her BPS busing lesson, she said, to address what the district wasn’t teaching. Now, as the city marks 50 years since the busing era strife, the district is attempting to expose more students to its painful history with a new curriculum spanning multiple days.

Through a partnership with the Boston-based curriculum developer Facing History & Ourselves, BPS is encouraging history teachers to incorporate lessons on the integration order and its fallout into their classes, including eighth grade civics, a required course for all middle school students.

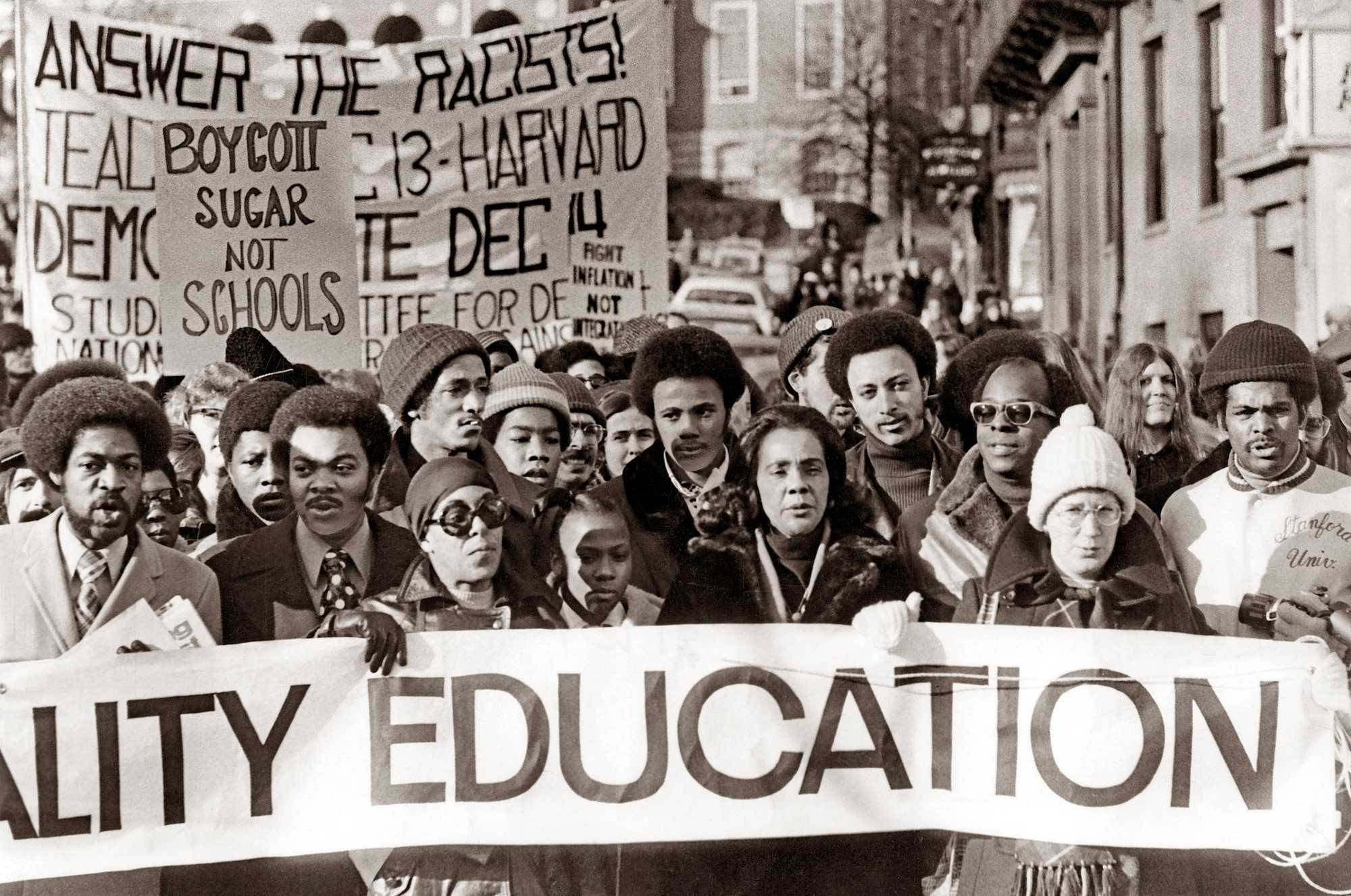

The new curriculum provides a broader picture of Boston’s history, going beyond the violent antibusing protests that rocked South Boston and Charlestown to highlight the decades-long quest by Boston’s Black families to get equal access to public education. The curriculum will also expose students to the perspectives of Latino and Asian American families, who also faced disruptions and prejudice during those years.

BPS is providing free training on the new curriculum to its teachers, but the district will not require its educators to teach it — a decision advocates who pushed for the curriculum call disappointing.

School integration was a “major chapter” in Boston’s history and teaching about it is an “opportunity that shouldn’t be missed,” said Lewis Finfer, a member of the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative, a community advocacy group.

“This is the most important event that’s happened in Boston in the second half of the 20th century, and it still reverberates today in how Boston looks at itself and how other cities see Boston,” he said.

Milton, a former BPS student who was bused from her predominantly Black neighborhood during the 1980s, recalls being angry that her teachers avoided the topic.

“As an educator, you have the responsibility to teach students, especially when this is your community, where you were born, were raised, where you go to school,” she said. “So for me, it’s my responsibility, because I never was taught it.”

During the busing lesson, Milton, a veteran educator and former BPS teacher of the year, explained the consequences of Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr.’s decision like a preacher in church, her arms in perpetual motion, her voice buoyant as music.

Fourteen-year-old Mark Pedro-Deas was rapt. With his classmates, he analyzed more photos from the era — protesters with cold stares and bold signs: “Charlestown against forced busing” and “Southie will fight.”

“People think, like, this only happened in the South,” said Mark, who lives in Hyde Park.

Angela Hedley-Mitchell, executive director of humanities for BPS, said she hopes all kids in the district will experience a lesson like Milton’s. She trains all new BPS teachers on the district’s history, but forcing educators to use the new busing curriculum could lead to halfhearted lessons, she said.

A young girl looked out of a bus window on her way to a new school in Boston on Sept. 12, 1974, the first day of school under the new busing system put in place to desegregate Boston Public Schools. (Bob Dean/Globe Staff)

“Instead of, ‘You have to come to this! You have to do that!’ I think you can get to people’s hearts and minds by the opportunity to engage,” she said.

BPS students whose teachers adopt the roughly two-week-long set of lessons will wade into Boston’s violent history of racism and exclusion, primarily focusing on the protests, boycotts, and legal actions organized by Black, Latino, and Chinese American Bostonians pursuing desegregation in the 1960s and 1970s. Students will draw connections between those efforts and the challenges to equity and justice in BPS today.

Peggy Kemp was a history teacher in her early 20s at the Solomon Lewenberg Middle School in Mattapan during the initial years of busing. She recalls giving her students, who were visibly shaken from watching the brutality, time to ask questions.

“There’s no way that you could really ignore it,” said Kemp, now retired.

But her classes didn’t spend a lot of time learning about the events that preceded the court order. She was instead focused on creating a welcoming classroom environment for both her Black neighborhood students and the white students bused in from nearby West Roxbury.

“What was most important was to convey to students that you heard their concerns and that, in your classroom, they were safe,” Kemp said.

Advertisement

By the turn of the millennium, many BPS educators still weren’t ready to talk about the district’s own history, said Fran Colletti, executive director of Facing History & Ourselves New England, a nonprofit curriculum developer.

“It was the elephant in the room at every meeting I went to,” Colletti said. “The trauma of that moment — of the violence, actually — and of two communities pitted against each other, people were reluctant.”

Hedley-Mitchell said the district is providing educators with instructional strategies for tackling the difficult conversations that can arise when teaching about busing and its legacy. Lessons in the new curriculum will culminate in student-led projects delving into challenges they see in their own communities.

“It’s a way for them to start thinking about justice: What do I see in my experience in education? What would I like to change?” said Hedley-Mitchell.

Student Mark Pedro-Deas said he believes his peers throughout the district deserve to know their own history.

“Knowing that, like, once upon a time, this happened in your community — you can’t just shake this off.”

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC