BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

To close the achievement gap, some schools take a holistic approach

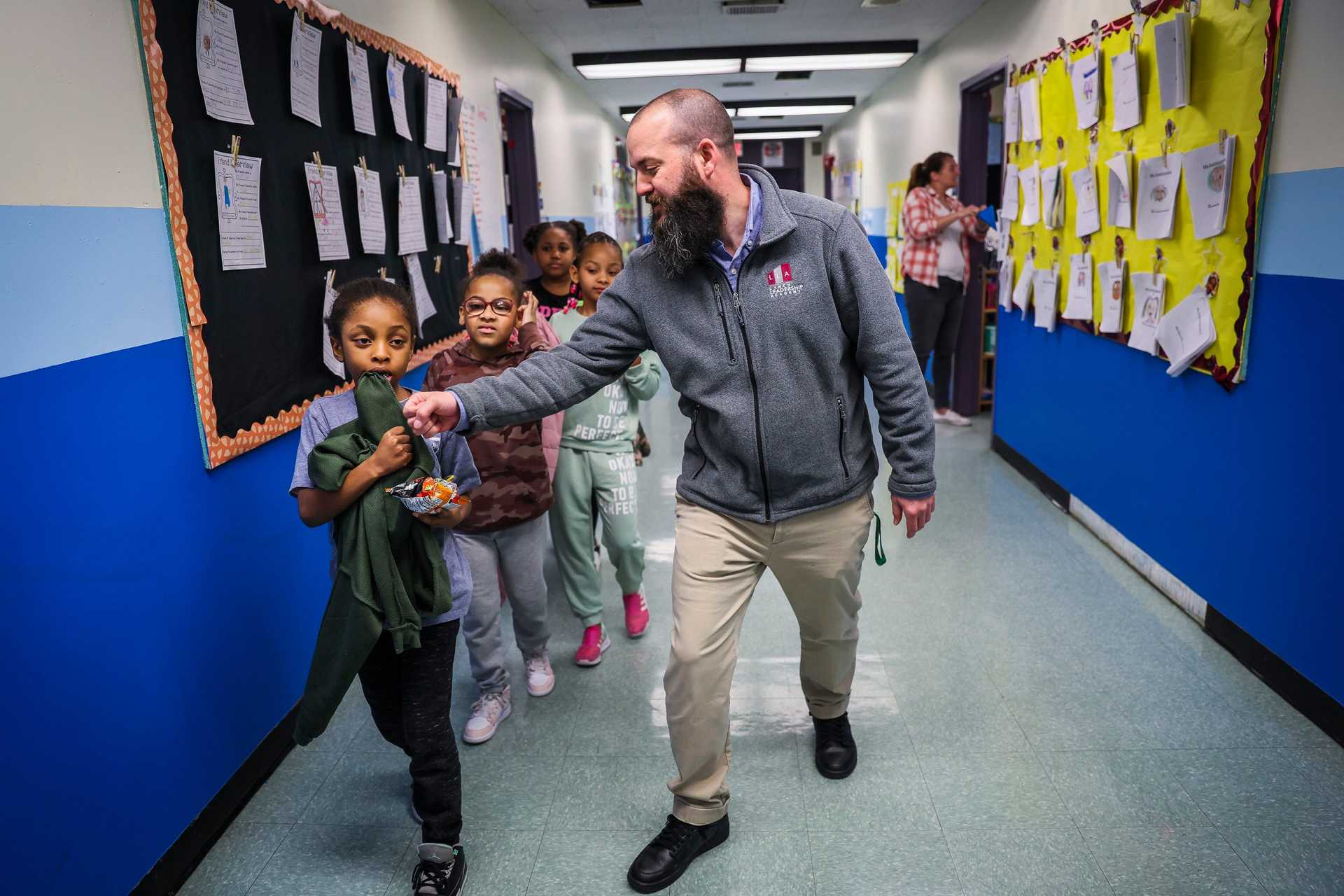

Walking through a corridor of the Joseph Lee K-8 School in Dorchester, principal Paul Kennedy opened a classroom door and beckoned visitors to look inside. The room was filled with racks of clothing and shelves of home goods, all of it free for school families to take.

“It’s an opportunity to come in and shop. You pick what you want,” he said. Everything is new, the tags still on. “It’s really about dignity.”

As he walked the hallways — stopping and picking up any stray piece of paper or napkin discarded on the floor — he pointed out other non-academic services. At a desk under a staircase, an occupational therapist guided a student’s hand as she learned to write. He said two clinicians sent by Franciscan Children’s hospital come to the school every day to provide students mental health counseling.

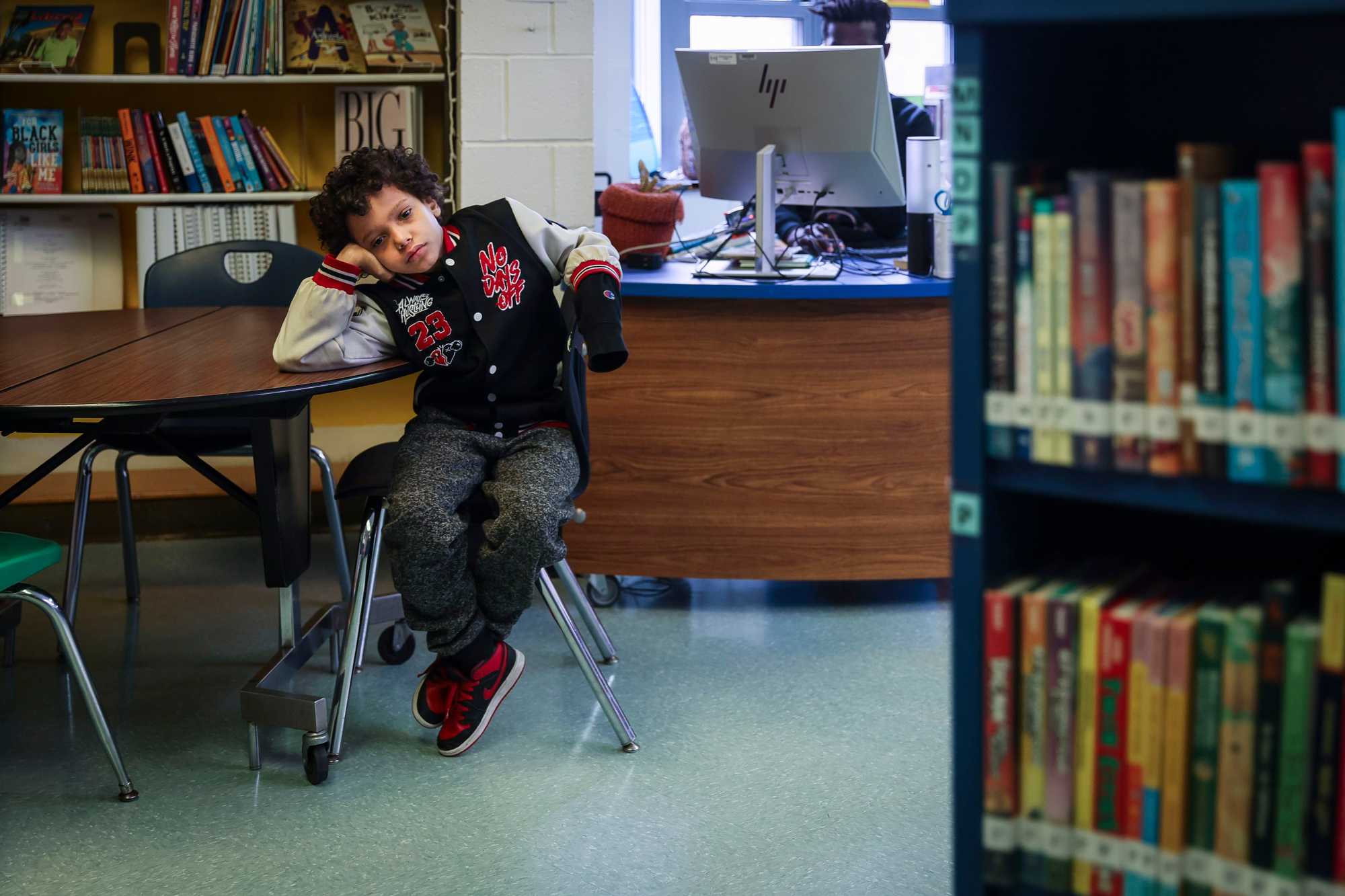

For Kennedy, the disadvantages his students face mean the school can’t just be a school. “We know that there’s a lot of factors outside of our control that are impacting [our students’] educational outcomes,” he said. “How do we support them and support their families?”

Hardships students face outside school walls, experts say, are the root causes of educational disparities. They argue that school districts will not achieve their goals of closing achievement gaps between the privileged and the disadvantaged until they remove, or at least minimize, the obstacles that hold so many students back.

At left, mural painted on the wall of Joseph Lee K-8 School honors two students who passed away in recent years. A room at the Lee is filled with racks of new clothing and shelves of home goods, all of it free for school families to take. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Advertisement

More than two-thirds of Boston Public Schools students are low-income, 23 percent have disabilities, and about 34 percent are still learning English. Most alarming of all: Approximately one in 10 students were homeless for at least part of this school year.

“We have a fundamental problem in this country with disparity of wealth and poverty,” said Mossik Hacobian, a longtime Boston organizer who helped found the nonprofit Higher Ground, which offers extracurricular services to families in Roxbury, Mattapan, and Dorchester.

“You have better-resourced families in better-resourced communities, providing enrichment programs for their kids without batting an eye just because they can afford it,” he said. “And you have families in Boston that are barely making ends meet. And we have not figured out as a system how to provide them what they need to succeed.”

There are different visions of what a school system, or a city, should do about that. Some favor antipoverty programs run by City Hall. But others argue that Boston should help young children and teenagers where they already are: at school.

In another hallway at the Lee, Kennedy flagged down Emma Furlong, a coordinator placed in the school by a nonprofit called City Connects. Furlong has no classroom duties. Her job is to evaluate the needs of every student at the school, and then address them. It could be filling out Medicaid forms so a student can access medical treatment or helping a homeless family find a place to stay.

Kennedy summed up the central challenge of Furlong’s job: “How are we going to give [families] what they need so we can give their child what their child needs?”

Studies have shown that the program works. Students at City Connects schools — there are more than 100 across the United States and in Ireland — score better on tests and graduate at higher rates than their peers at similar high-poverty schools. And the results persist. One study found that City Connects reduced the dropout rate of Black and Latino boys by half, while another found it increased college completion rates by half.

BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper is rolling out something similar called the Community Hub Schools model. Like the City Connects program, hub schools also strive to meet students’ urgent non-academic needs — medical treatment, food insecurity — and also provide extracurricular activities that low-income families might not be able to afford. She is also planning to provide special education services in every classroom. That way students with disabilities don’t have to bus to schools with specialty programs.

The long-term goal is for every school in the district to offer these services.

These kinds of programs are evidence-based and education leaders broadly agree they should be expanded. But they’re not magic.

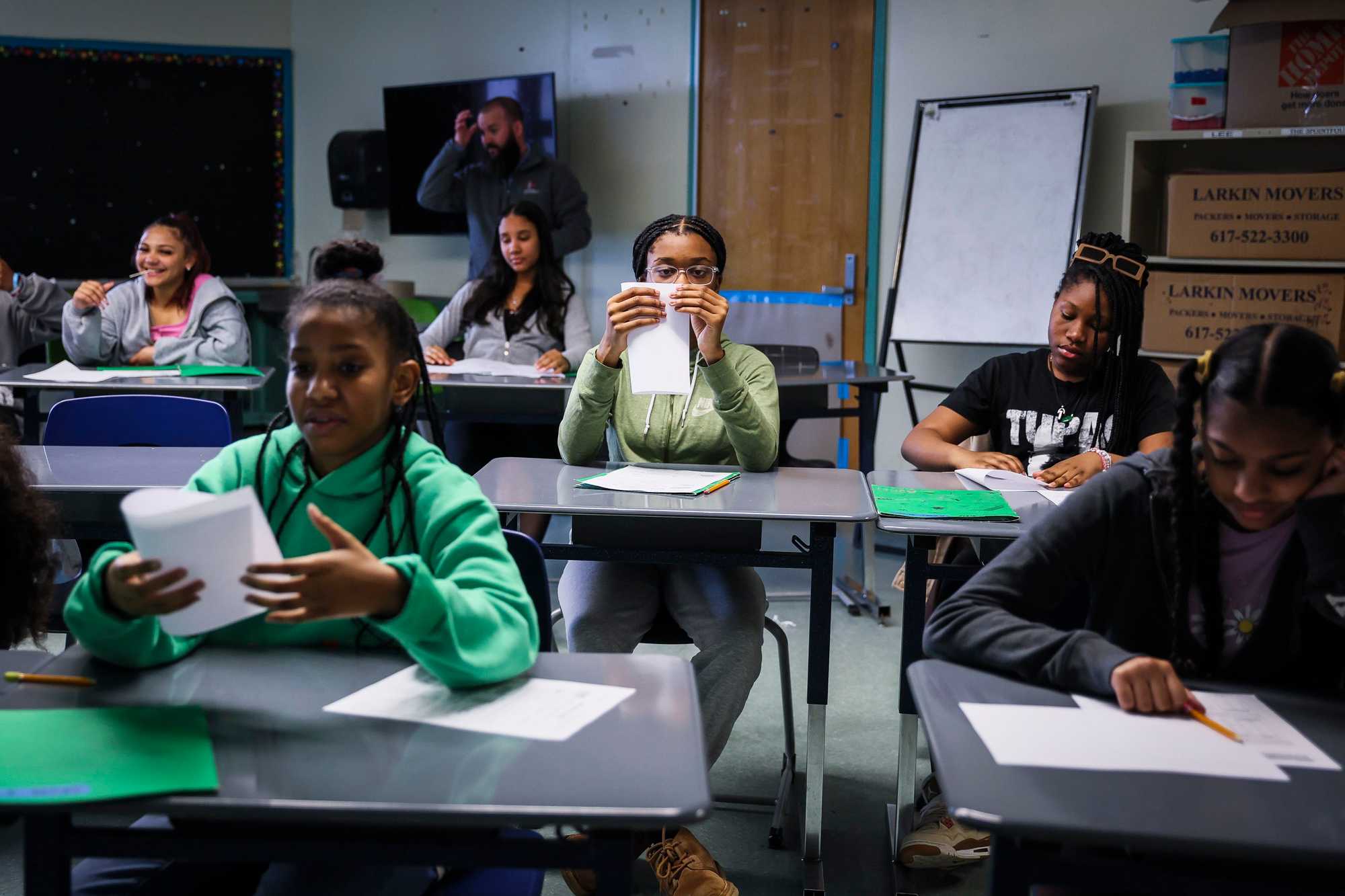

The Lee has shown that. Its staff is full of people desperately trying to provide a good education to the city’s children, but faculty and students are contending with decades worth of structural racism that created and propped up the economic segregation affecting families in surrounding neighborhoods.

The school was built in the early 1970s for the express purpose of creating an integrated and, it was hoped, fairer and higher performing Dorchester school. The brand new, multimillion-dollar building with a large auditorium for the arts and a brand new gym was supposed to attract both white and Black students. But white families revolted; they demanded to stay in their majority-white schools.

Advertisement

How much has the Lee changed since then? Its staff is much more diverse — about 40 percent are Black and Latino. Its funding, more than $35,000 per student, is high. It offers in-school services that were unheard of in the district 50 years ago.

But issues abound. It remains segregated; nearly 90 percent of its students are Black and Latino. More than three-quarters of the students are low-income. The average student at the Lee missed more than three weeks of school last year. During standardized testing in 2023, only 7 percent of the school’s students demonstrated grade-level proficiency in English. Only 2 percent tested at grade level in math.

Kennedy said the non-academic services the Lee offers are only a fraction of what would be needed to help the school’s students catch up.

And despite the services the school does offer, many local parents believe the Lee is not good enough for their children.

Kennedy, the school’s principal, doesn’t blame them. There are those who love his school, he said. “But that doesn’t mean that they haven’t had experiences with education in Boston that left them distrustful.” He wonders how he fits into that history himself.

“Am I truly changing things?” he said. “Or am I doing more of the same?”

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC