This story is best experienced with audio.

176 days, 25 officers: The pursuit of Robert Card proved a case study in how not to prevent a mass shooting.

Wherever he went, Robert R. Card II thought he heard people talking about him. Behind his back coworkers, longtime friends, people he just met were calling him a sex offender and a pedophile. He could hear them, he said, and he was becoming increasingly angry and paranoid. Also drinking heavily. A trained marksman in the Army Reserve, Card talked of committing a shooting. And he had access to guns. Lots of them.

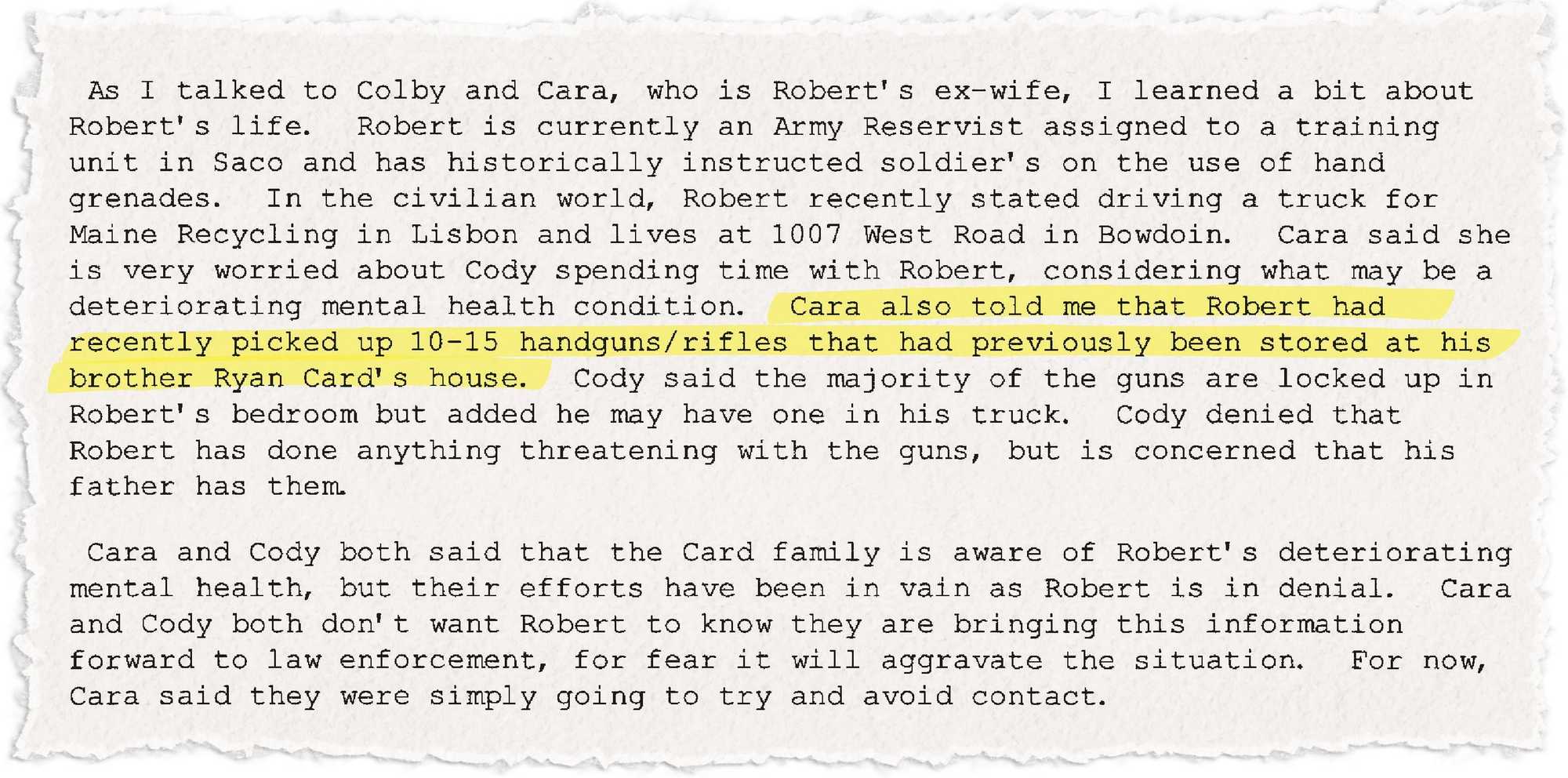

His son, Colby, a senior at Mt. Ararat High School, was worried. He had watched his father’s mental health spiral down and knew his father had 10 to 15 guns in his bedroom, maybe even one in his truck. Colby and his mother, Cara, shared their concerns first with a school resource officer, and then a Sagadahoc County sheriff’s deputy summoned to the school.

That conversation at the high school last May marked the beginning of a nearly six-month span in which at least 25 police officers were repeatedly alerted to warnings from family and Army colleagues about Card’s erratic behavior and his rantings about shooting people. In one encounter with police, Card chillingly told officers, “I am capable.”

There were at least two opportunities for authorities to take his guns away.

Law enforcement officials, however, never detained him or took away those guns. On the night of Oct. 25, months after his son asked for help, Card picked up a rifle equipped with a scope and a laser sight, walked into the Just-In-Time Recreation bowling alley in Lewiston, and fired 18 rounds in 45 seconds, fatally shooting eight people and injuring three more. Shortly after, he drove four miles to Schemengees Bar and Grille, where he fired three dozen rounds in 78 seconds, killing 10. Ten others were injured.

A commission appointed in November by Maine’s governor to investigate the killing spree gathered extensive evidence and took testimony at seven public meetings. It concluded, in a report issued March 15, that law enforcement had plainly failed in its duty to try to stop Card from doing what he had said loud and clear he might do.

Local police failed to take Card into protective custody, the commission said in the report, and delegated the job of securing Card’s weapons to his own family — which the report said “was an abdication of law enforcement’s responsibility.”

The Boston Globe, meanwhile, conducted its own review, and found an even more disturbing picture.

Shooting suspect, and his troubles, well known in his communityAn examination of 36 hours of police video, audio transmissions, and commission testimony and more than 600 pages of publicly released documents yielded the most comprehensive tally yet of how many times officers were warned about Card’s intentions, and how explicit some of those warnings were ― including those from Card himself.

It was failure on a mass scale.

What follows is a day-by-day recounting of the recorded moments when law enforcement and military officials were asked to take action and stop Card. The Globe contacted each of the 25 officers who were warned about Card. Most did not respond to repeated attempts for comment. The few responses the Globe received were in defense of the officers’ actions.

Advertisement

May 3, 2023 - 176 days until shootings

Topsham, Maine

The first warning seemed scary enough, by itself. In the office of the school resource officer at Mt. Ararat High School in Topsham, Colby Card and his mother, Cara Card, told Sagadahoc Sheriff Deputy Chad Carleton that Colby had watched his father becoming paranoid and angry over the last few months for no apparent reason. When the two were out in public together, Card claimed people were talking about him, or calling him a pedophile, even while no one was nearby.

Army personnel file shows Maine reservist who killed 18 people received glowing reviewsCara Card, who divorced Robert Card in 2013, said her ex-husband had also recently picked up 10 to 15 guns from his brother’s house.

They agreed on a plan of action: Carleton would reach out to Card’s Army Reserve unit, which is based in Saco, Maine, to get them involved in trying to get Card some help.

Audio: Call from school resource officer

00:00

00:00

In later phone calls with Cara Card and Card’s brother, Ryan, Carleton learned that Robert Card had been ranting about having to shoot someone — in records, it’s unclear whether Card was referring to anyone in particular.

Ryan Card had seen the heavy drinking and heard the rants, though he didn’t know the extent of his brother’s paranoia or that he might have been hearing voices.

First Sergeant Kelvin Mote, one of Card’s Army supervisors who is also an Ellsworth police officer, told Carleton that Card had been accusing other soldiers of calling him a sex offender. It’s unclear what, if anything, provoked those claims.

A training exercise involving the use of weapons and grenades was coming up soon. Mote said he’d reach out to another supervisor to develop a plan to get Card some help, and he’d keep in touch.

On the night of May 3, Ryan Card and his sister Nicole visited their brother. He answered the door holding a gun. People were outside, casing his house, he told them.

But there was no one there.

May 4 - 175 days until the shootings

Bowdoin, Maine

In Carleton’s report of these discussions, he said he warned Mote to be careful, because Card had answered the door with a gun the day before.

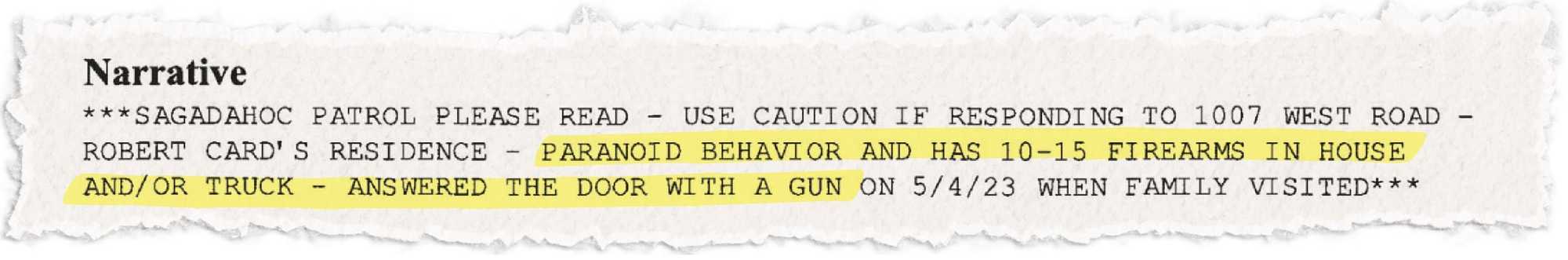

Maine authorities could have moved to seize gunman’s firearms before shootings, experts sayAt the top of his report, Carleton offered this warning to fellow officers about Card: “USE CAUTION... PARANOID BEHAVIOR AND HAS 10-15 FIREARMS IN HOUSE AND/OR TRUCK - ANSWERED THE DOOR WITH A GUN.”

In March, months after the shooting, Mote told the state commission that he was not aware of any follow up efforts by the Army to get Card mental health help. Mote never spoke to Carleton again, he told the commission.

June 2 - 146 days until the shootings

Carleton received a call from Ryan Card, who told the officer that his family was concerned about his brother’s behavior and wanted to try to get him admitted into a Veterans Affairs hospital. Carleton texted Mote, who never got back to the deputy or Card’s family, according to records. Mote did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

July 6 - 112 days until the shootings

Poland, Maine

Card legally purchased a .308 Ruger SFAR semi-automatic rifle from Fine Line Gun Shop in Poland, Maine. The rifle was later used in the shootings.

July 15 - 103 days until the shootings

Cortlandt, N.Y.

While at Camp Smith — a military installation in Cortlandt, N.Y., operated by the New York Army National Guard — Card and some other soldiers headed to a convenience store for beer. In the store’s parking lot, Card accused three reservists of calling him a pedophile. He got in the face of one of them — a longtime friend — and shoved him. The soldiers calmed him down enough to get him back into the car.

On the way back to the hotel where the soldiers were staying, Card repeatedly said he would “take care of it.” When asked what he meant, he didn’t respond, and he locked himself in his hotel room for the night.

Mote and others got a key to Card’s motel room and opened the door. Card responded by trying to slam the door in Mote’s face.

Card told the group he wanted people to stop talking about him. Mote assured him that no one was talking about him.

Among the reservists present that night were two police officers. The next morning, Mote reported the incident to the New York State Police.

July 16 - 102 days until the shootings

Cortlandt, N.Y.

New York State Police troopers called to Camp Smith were told that Card had been drunk the night before and had threatened his fellow soldiers. His mental health had been in decline, they told the troopers.

The troopers met with Card, informing him that his colleagues were concerned about his welfare and that the camp staff had ordered Card to receive a mental health evaluation.

“Oh, because they’re scared because I’m going to, freaking, do something,” an agitated Card replied. “Because I am capable.”

“What do you mean by that?” one of the troopers asked.

“Nothing,” Card replied.

On video, Lewiston shooter told N.Y. authorities he was ‘capable’ of violenceCard was evaluated that day by a psychologist at Keller Army Community Hospital in West Point, then taken to the Four Winds mental health hospital in Katonah, N.Y., for evaluation and treatment. After 14 days, he was released with a recommendation to his unit Army Captain Jeremy Reamer that his access to military weapons be restricted.

The staff also recommended that his firearms at home be taken away. The commission found that Reamer did not share this information with Maine law enforcement.

August 3 - 84 days until the shootings

Bowdoin, Maine

Card returned to his home in Maine. Card’s company commander was notified by Army officials that while on military duty Card should not have access to a weapon, handle ammunition, or participate in live-fire activity. Card was declared “non-deployable.”

August 5 - 82 days until the shootings

Auburn, Maine

Card went to Coastal Defense Firearms in Auburn, Maine, to pick up a silencer he had purchased online.

On a form at the store, Card marked “yes” to a question asking whether he had “ever been adjudicated as a mental defective or committed to a mental institution.” Card was told he could not take the silencer home.

September 15 - 41 days until the shootings

Bowdoin, Saco, and Ellsworth, Maine

2:04 a.m.

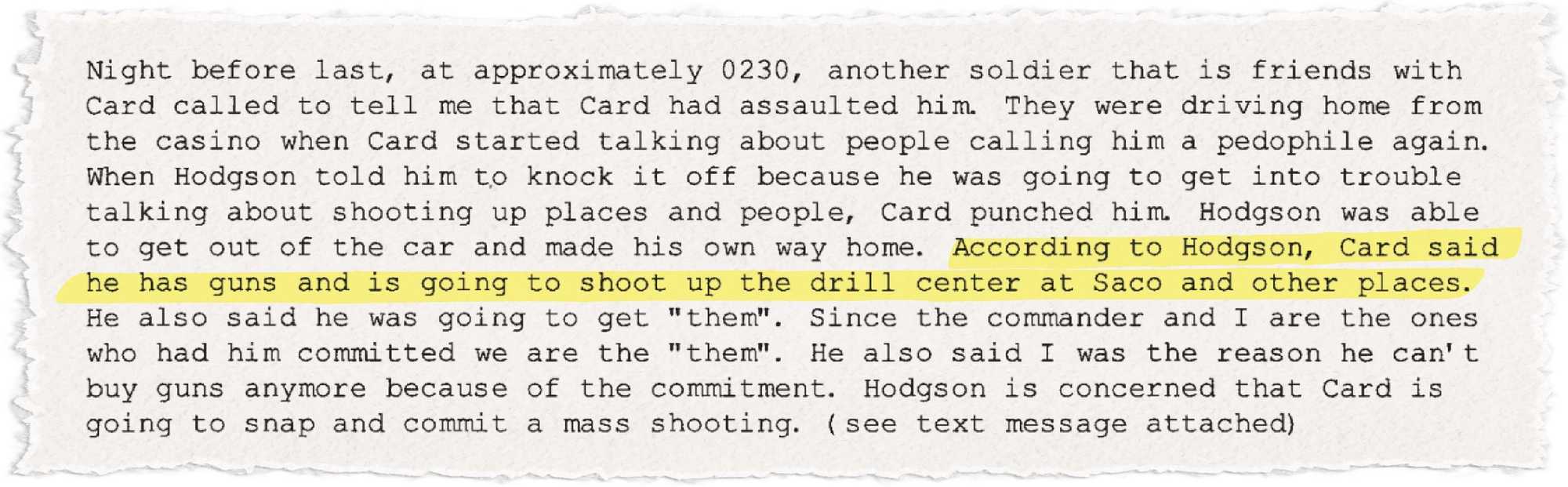

Army reservist sent texts before Maine attack warning gunman would ‘do a mass shooting’Sean Hodgson, a staff sergeant in Card’s unit, texted Mote to warn him that Card might snap and commit a mass shooting. The two had been driving home from a casino in Oxford when Card started talking about people calling him a pedophile and “shooting up places and people” including the Army Reserve base.

Hodgson, a close friend, told Card to knock it off. Instead, Card punched his friend in the face.

“Change the passcode to the unit gate,” Hodgson texted to Mote.

A state commission investigating the shooting later said Hodgson was “at a minimum” an assault victim. But he was never interviewed by the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office, even though the office was told about the incident.

Card could have been taken into custody and criminally charged for the assault, and prosecutors could have requested bail conditions that prohibited Card from having weapons, the commission found.

When Mote saw the texts, he reached out to a senior supervisor, who is also a Maine state trooper, who told Mote to ask police to conduct a welfare check on Card at his home in Bowdoin.

Sheriff’s deputies who received warnings about Lewiston shooter acted appropriately, outside review findsIn a memo that he drafted about Hodgson’s concerns, Mote said he would prefer to err on the side of caution, because Card “is a capable marksman and, if he should set his mind to carry out the threats made to Hodgson, he would be able to do it.” The memo was shared with the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office.

A member of the Ellsworth Police Department, acting on behalf of Mote, contacted the sheriff’s office about the Army reserve unit’s concerns about Card’s mental health and Card’s threat to “shoot up” the Army reserve facility in Saco.

Audio: Ellsworth police Detective Bagley calls Sagadahoc County Sheriff's office

00:00

00:00

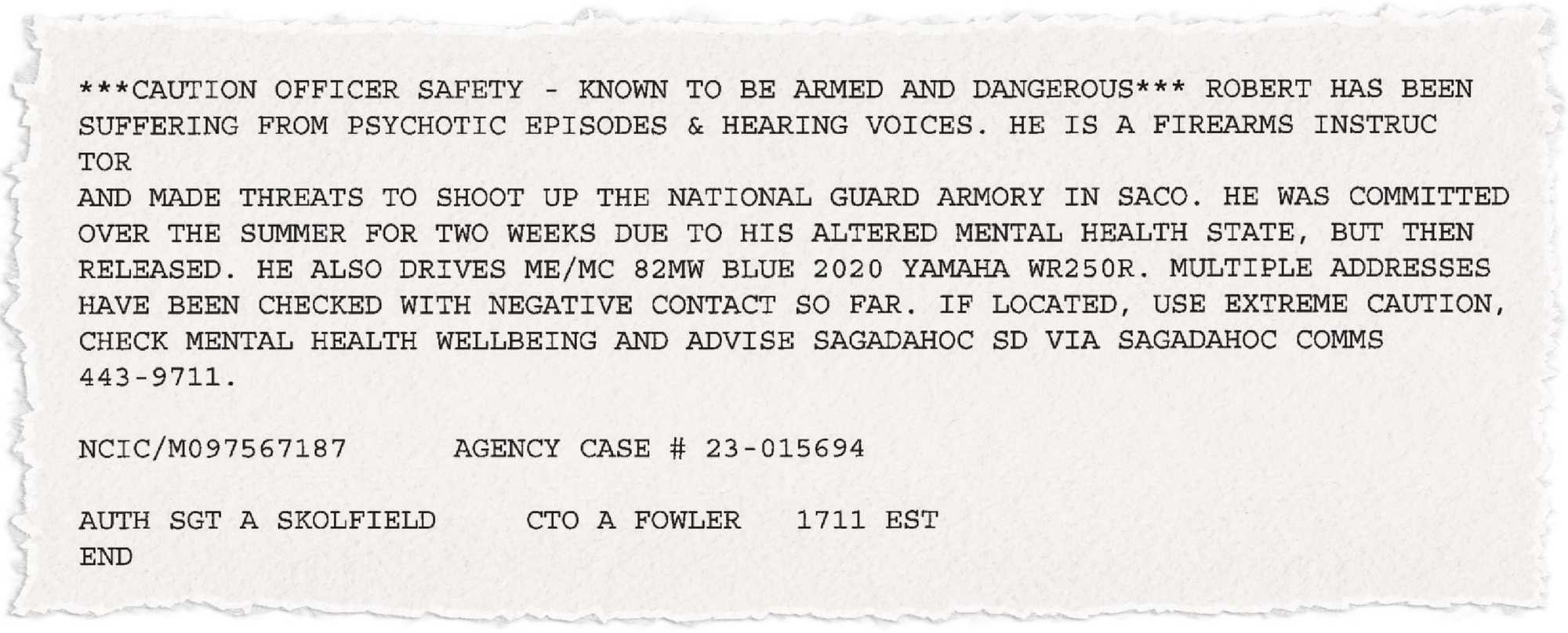

Sergeant Aaron Skolfield of the sheriff’s office was assigned to conduct the well-being check. While he later wrote in a report that the threats should be taken seriously, his words at the time suggested he considered it a routine assignment.

“I’m going to [do] a welfare check on Robert Card,” Skolfield was heard saying on a recording of the police transmission. “And he’s flagged in-house, ‘Known to be armed and dangerous. Blah, blah, blah.’ "

Audio: Welfare check on Card

00:00

00:00

Skolfield drove to Card’s trailer in Bowdoin, but no one was home. He asked two officers on the department’s evening shift to check on Card, but they did not find Card either. There is no record Card was ever confronted by the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office.

Maine gunman’s ex-wife, son warned authorities in May he was hearing voices, had arsenal of guns, documents showSkolfield requested an alert about Card, known as a File 6, be sent to every law enforcement agency in Maine. The alert asked police to keep an eye out for Card, but it didn’t grant permission to detain him.

File 6 alerts are relatively common and rarely trigger a special response on their own.

The Card alert got no response. Five days after the shootings, a spokesperson for Lewiston police said they had not yet found Card’s File 6, which would have been buried under hundreds of others.

September 16 - 40 days until the shootings

Saco, Maine

2:17 a.m.

Audio: Army Lieutenant Yurek calls Sergeant Monica Fahy, Saco police

00:00

00:00

Another member of Card’s reserve unit called the Saco Police Department about Card’s threat the previous day to shoot up the base.

The reservist, who is a police officer in Brunswick, warned that the base’s gate limits access and that police wouldn’t be able to get in quickly if they had to. “We’ll do what we have to” on the base, he said, if Card showed up.

Audio: Sergeant Fahy, Saco police

00:00

00:00

6:45 a.m.

Saco police officers in patrol cars are stationed around the Army base. But Card never shows.

7:46 a.m.

Two Saco police officers admitted to the base interviewed Reamer, a captain in Card’s unit and a Nashua police officer. The officers hoped to do a “well-being check” because of Card’s threats.

Reamer said he didn’t think the Saco officers needed to keep watching for Card. If Card were to appear at the base, the reservists would call police, he told them.

“We’ll do our best to kind of de-escalate and handle it on our end,” Reamer said.

Reamer downplayed the warnings about Card. The warnings came from a source who “is not the most credible of our soldiers,” he said.

8:45 a.m.

County sheriff’s office defends response to warnings about Lewiston shooterSkolfield and a Kennebec sheriff’s deputy arrived at Card’s trailer to speak with him.

The officers heard Card moving around inside the trailer, but he refused to answer the door. According to Skolfield, the officers were in Card’s line of sight, and therefore at risk, so they backed away. The Kennebec officer left.

Skolfield parked his car within view of Card’s driveway and waited. He tried calling Card.

Officer Jeremy Reamer, Nashua police, on left, Sergeant Aaron Skolfield, of Sagadahoc sheriff's office on right

10:46 a.m.

Skolfield reported to Reamer that Card wouldn’t come to the door. The two talked about Card’s guns: No one knew if his family had secured them.

Maine law enforcement knew shooter posed a threat but were concerned about confronting him, video showsThe two men talked warily about the risks of moving more forcefully to persuade Card to get help — or to detain him.

“I don’t think this is gonna get any better,” Reamer said. ”He’s refusing any real medical treatment. I mean, we got it as much as we could. But you know, you can lead a horse to water but if he’s not gonna drink it, then there’s not much we can really do.”

Skolfield replied, “there’s the yellow flag laws. So when there’s someone who’s a danger to themselves or others, there’s a process which we’re supposed to go through to seize their weapons if they are deemed a danger to themselves or others.”

Audio: Sergeant Skolfield calls to Army Captain Reamer

00:00

00:00

“At the same time, we don’t want to throw a stick of dynamite into a pool of gas either and make things worse,” Skolfield said.

The state commission investigating the shooting determined that the Sagadahoc Sheriff’s Office had sufficient information at that point to start the process for securing a yellow flag order against Card. The process requires police to take someone into protective custody and be evaluated by a mental health professional before they ask a judge to restrict their access to weapons.

11:34 a.m.

Skolfield left Robert Card’s property late that morning.

He visited the Bowdoin home of Card’s father, Robert Card Sr., in an attempt to contact Card’s brother. Card’s father did not appear familiar with the status of Card’s weapons, and Skolfield said he would try contacting Robert Card again.

Full coverage of the Lewiston shootingsThomas Nolan, a policing expert who served as a Boston officer for 27 years and who has no connection to the Card response, told the Globe that the Sagadahoc Sheriff’s Office “dropped the ball.” He faulted the office for not ensuring they made contact with Card.

“Cops just don’t turn around and walk away just because someone doesn’t come to the door,” Nolan said. They call for assistance, he said.

September 17 - 39 days until the shootings

On this day, a little more than a month before the mass shooting, Skolfield spoke briefly with Card’s brother about the status of Card’s guns. Ryan Card told Skolfield that his family would move Card’s weapons from a safe at the family farm to a place where he would not have access to them.

At that point, Skolfield, who was scheduled to leave for vacation the next day, determined that Card’s case was resolved. His office, he believed, had done all it could at that point.

Skolfield told Card’s brother that if the family ever thought Card needed a mental health evaluation, they should call the police.

There is no record of further contact between the sheriff’s office and the Card family until the night of the shootings. The investigative commission determined that putting the responsibility of securing Card’s weapons on his family was an “abdication of law enforcement’s responsibility.”

October 18 - 8 days until the shootings

More than two weeks after returning from vacation, and having had no further contact with the Card family, Skolfield canceled the File 6 warning about Card.

The Sagadahoc Sheriff’s Office later explained that the warning was canceled because the department had received no further concerns or calls about Card from his family or from the Army.

October 25 - Day of the shooting

Lewiston, Maine

There were more than 60 people inside, including 20 children, when Card entered the Just-In-Time Recreation bowling alley before 7 p.m. Eight would die of gunshot wounds; three were wounded.

At Schemengees Bar and Grille, Card killed 10 and wounded 10 more.

The victims ranged in age from 14 to 76.

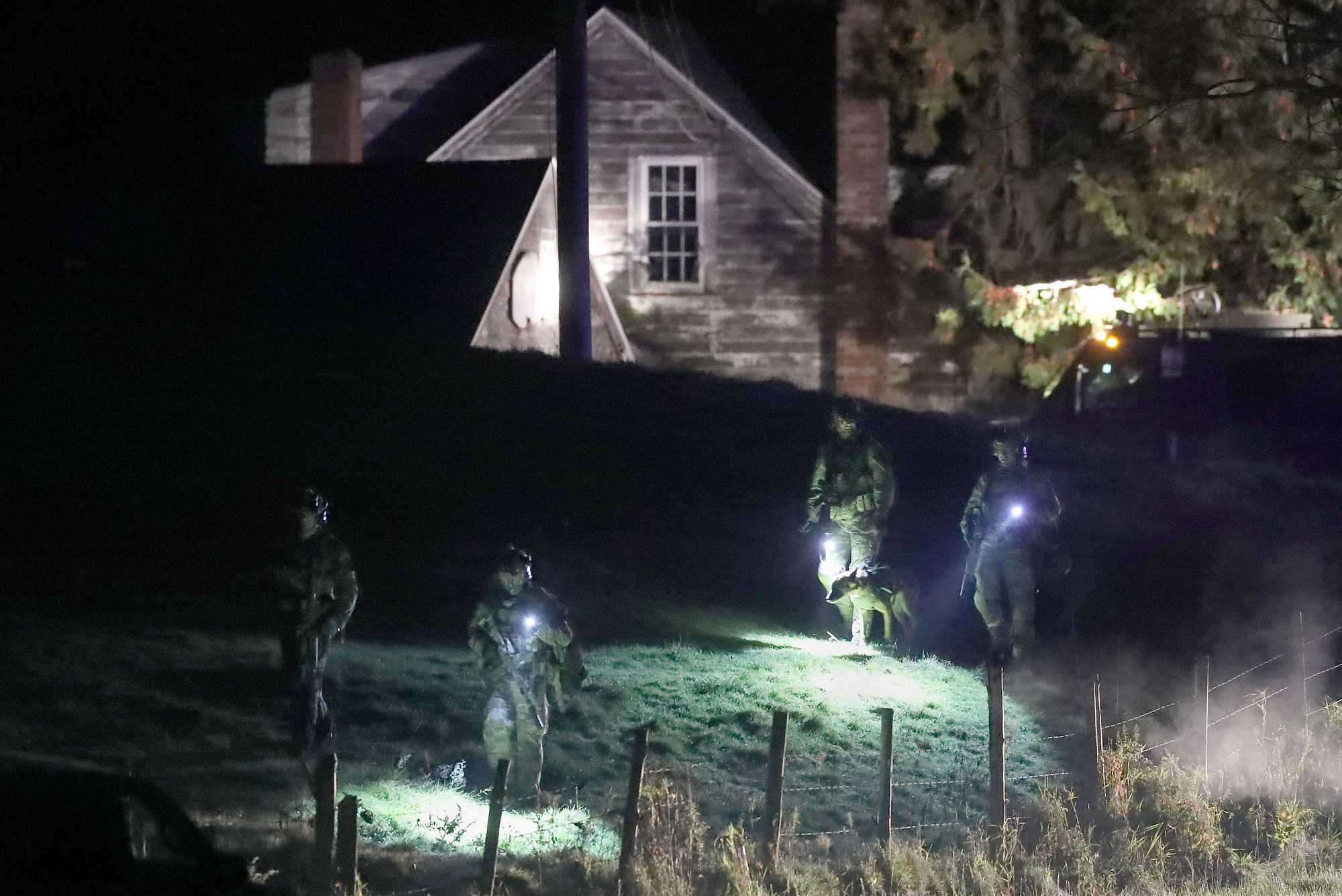

Following a two-day search, authorities found Card dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in nearby Lisbon.

Maine shooter had signs of traumatic brain injury before Lewiston rampage, according to BU studyThe Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center at Boston University found that Card’s brain showed evidence of significant traumatic brain injury at the time of the shootings and likely contributed to his symptoms.

In a preliminary report released on March 15, the state’s independent commission determined that the Sagadahoc County Sheriff’s Office failed to use its legal authority to place Card into protective custody and take his guns.

Many of the survivors and victims’ loved ones have demanded the commission take steps to prevent a future tragedy and hold authorities who failed to act accountable.

Danielle M. Jasper, who survived the shooting at Schemengees along with her husband, John, who was wounded, testified before the commission. They attended the funerals of seven friends killed in the shooting.

“Let that sink in: seven funerals. Who goes to seven in a year,” she said through tears, “let alone weeks?”

Jasper ended her remarks with a plea.

”When there is someone who is a danger to themselves, or to the community, do the uncomfortable task and protect us,” she said.

Travis Andersen, Laura Crimaldi, Sean Cotter, John R. Ellement, Samantha J. Gross, Hanna Krueger, Victoria McGrane, Emma Platoff, Sarah Ryley, Ivy Scott, and Nick Stoico of the Globe staff, and correspondent Daniel Kool contributed to this report.

Design and development by Ryan Huddle and Daigo Fujiwara.

Advertisement