The Great Divide

Lost in a world of words

Learning to read is the greatest gift a school can give a child. And yet here, in the birthplace of public education, outmoded teaching methods leave thousands of students struggling to gain this critical skill.

First in a series of stories examining the literacy crisis in Massachusetts

LOWELL — Rosalinda wants to be an astronaut when she grows up. Every time she says it, her mother, Maritza Alvarado, feels a gust of pride in her chest — and then a twist of dread in her gut. Rosalinda, who is 10 years old, is reading well below grade level.

Alvarado doesn’t know what to do. She is a chef and a single mother; for her daughter, she wants a future of boundless possibility. The teachers at school have said not to worry, Rosalinda, a fifth-grader, doesn’t have a learning disability. But her report card for reading said “2″ — “partially meets expectations” — all last school year, same as the year before.

In the evening, with Alvarado busy at the stove, Rosalinda begrudgingly reads aloud at the kitchen table, skipping words she doesn’t know. When Alvarado pauses to help, Rosalinda slams her book shut. Without quick improvement, Alvarado knows how tough it will be for Rosalinda to do well in upper grades and get into college — in short, to set her life’s course.

“It breaks me,” Alvarado said. “It breaks me, because I want her to be where she needs to be.”

It is a disaster hiding in plain sight: Every year, thousands of children across Massachusetts miss a crucial milestone and predictor of their ability to thrive later in life — being able to read proficiently by the end of third grade. A kind of mass academic drowning, this system failure is plainly apparent in state test score data.

Massachusetts is the birthplace of public education, and students here outperform their peers nationally in virtually every measure of academic achievement. But pride in those numbers obscures the other side of the picture: Before the pandemic, only about half of public school third-graders had adequate reading skills. Post-pandemic, the story is even worse.

Scores for all third-graders have slipped below the 50 percent mark, and the most vulnerable kids are in serious trouble; 75 percent of low-income third-graders could not pass the reading comprehension test on last spring’s MCAS exam. Roughly 70 percent of Black third-graders, 80 percent of Latino students, and 85 percent of children with disabilities couldn’t understand grade-level reading passages well enough to answer questions about them accurately.

It bears repeating: The vast majority of Black and Latino children and kids with disabilities are being sent off to the fourth grade — where students start reading to learn instead of learning to read — hobbled by this major deficit, which has cascading effects on spelling and writing as well. Some can’t sound out words on the page. Others can’t understand what they’re reading. Many never catch up; they drop out of high school or fail to finish college. The social and economic rifts in our society widen.

And how have Massachusetts’ Legislature and educational establishment responded to this appalling state of affairs? By largely failing these neediest learners, an investigation by the Globe’s Great Divide education team shows.

Yes, the Legislature approved a law aimed at improving third grade reading proficiency more than a decade ago, but little came of it. At least 30 states, but not Massachusetts, have since passed literacy reform laws addressing this crisis.

Here, there is no requirement that schools use instructional methods grounded in the science of how children learn to read, an approach which teaches kids to sound out words phonetically rather than guess, and helps them build a store of knowledge about the world early on, instead of skipping from topic to topic. These methods are often called “structured literacy,” or “evidence-based” reading instruction. They mark a return, in many ways, to a system of nurturing young readers familiar to earlier generations.

A Globe survey found nearly half of the state’s school systems last year stuck with another approach to reading instruction, using curriculums marketed by educational publishers — lessons the state calls “low quality.” Some of these schools are in cities and towns renowned for their public schools; in those communities, too, the most vulnerable students are too often left struggling to read.

The state department of education is working hard to reverse this trend, and making progress, but lacks the authority and money it needs to hasten change and to overcome resistance from administrators in some districts.

“Honestly, the pace of that adoption is too slow,” said Jim Peyser, former state education secretary. “And in particular for low-income communities and where the reading gaps are the greatest, I don’t know if we have the time to waste.”

Many factors influence a student’s reading skills — from preschool preparation to whether their basic needs are met — which makes it all the more imperative that schools deliver on excellent instruction.

A better curriculum, though, is just a start; the state also needs teachers trained in the latest instructional methods. But many teacher education programs are turning out graduates without a grounding in the most effective way to build reading skills. At the same time, the state has not invested in roles like literacy coaches, which experts say are crucial for sustaining lasting change, especially among the students lagging furthest behind.

The Legislature in 2018 did pass a law that led to mandatory early testing of children for reading problems — it finally took effect this fall — but lawmakers have not directed money toward kids with dyslexia and older students still struggling to read, to make sure they get the tailored, intensive help they need.

The pandemic shook the entire education system to its core. While other states have since funneled huge sums of state money into early literacy initiatives — including $115 million in North Carolina and $174 million in Ohio — Massachusetts’ 2024 budget allocates just $5.3 million in state revenue to this pressing need. Here, also, districts haven’t been required to spend any of the billions they’ve gotten in state and federal money since the pandemic on improving reading instruction.

Beacon Hill’s relative indifference has resulted in some wounding comparisons with states with more aggressive literacy initiatives. Poor children learning to read are now slightly better off going to school in Florida or Mississippi — states that got serious about early literacy years ago — than they are in Massachusetts.

The serious lag in reading attainment is evident in all corners of the state. In Plymouth, reading tutor Patricia Smith’s “first job is to break bad habits” wrought by ill-informed instruction. In Reading, Lauren Andreottola’s 7-year-old son melts down in the mornings before school because his friends can read and he can’t. And in Springfield, April Brown-Lebron said her 14-year-old sister, whom she cares for, was not given special instruction at all last year, other than a computer program, despite reading at a mid-elementary level.

“The walking wounded are all over the place — kids that have been crippled and damaged,” said Richard McManus, a longtime reading tutor on the South Shore.

Now, many advocates are calling on Massachusetts to pass its own comprehensive literacy law to help schools improve faster. But teachers unions oppose state mandates on curriculum choices, and it’s not clear whether lawmakers, with their entrenched deference to local control, have the will to tackle the full dimensions of the state’s reading problem.

“The walking wounded are all over the place — kids that have been crippled and damaged.”—Richard McManus, a longtime reading tutor on the South Shore

What is clear: Every year, thousands of kids are scraping by, moving to the next grade, and then the next, without a good grip on the most important tool they need to succeed in life.

“I really do have that question in my head of like, how the hell did this child get to the 10th grade and they can’t read?” said Cambridge high school teacher Lily Rayman-Read. “That’s a whole systemic failure.”

Nine-year-old Isaac Osorio wants to read bigger books, books with longer sentences and harder words. But he’s stuck, unable to move on from beginner texts, whose pictures and predictable word patterns help signal what the jumbles of letters he sees on the page say.

“Winter is here,” he read one recent evening, opening a picture book to a page he’d memorized. “Sleep, bear, sleep. Winter is here. Sleep, snake, sleep.”

It’s something most people take for granted, the ability to read. But for the tens of thousands of Massachusetts children like Isaac who struggle to decipher the words in front of them — whether at school or on a McDonald’s menu — it is a brutal test of self-esteem, day in and day out.

Isaac feels calm and confident in math, but when his Lowell elementary school class switches to reading, he gets nervous, unless a teacher is right by his side.

“It’s kind of difficult,” he said, tugging at his black curls.

Advertisement

His mother, Gardenia Osorio, still in scrubs from her job as a medical assistant, listened nearby, tending to a scalding pan of fried ribs. She worries for her boy, who is just starting the third grade.

“I don’t think how they’re teaching kids to read is working,” Osorio said.

That’s just it. How schools teach students to read matters, and in a big way.

Reading, unlike speech, doesn’t come naturally to humans. Over decades, cognitive scientists studying the brain’s inner workings have discovered a reading circuit. To turn it on, many early readers require explicit instruction in how to sound out words using phonics. The phonics lessons work best if they’re sequential, building from one skill to the next.

It’s not just phonics, though. Early readers need to understand what they’re sounding out. Research has found that teachers need to push kids to read demanding texts and help them build a rich vocabulary and broad understanding of the world around them.

Structured literacy combines these two elements — phonics and knowledge building. A wide body of research, often referred to as “the science of reading,” shows this kind of instruction works best for most kids.

But in Massachusetts and across the country, reading research often hasn’t trickled down to classrooms. Many teachers, deprived of this knowledge in their degree programs, do the best they can with what they know, but the methods they have been told to use can set kids up for frustration, or failure.

Beginning in the 1980s, many schools dropped phonics, viewing it as overly didactic and boring. If kids spent enough time with books that interested them, the thinking went, they’d pick up reading on their own. Children should have room to explore what interests them, rather than being micromanaged by a teacher, according to this well-intended school of thought.

By the late 1990s, most Massachusetts districts were incorporating some phonics, switching to a hybrid approach known as “balanced literacy.” In recent years, many districts, including Lowell, have intensified their phonics instruction.

The problem is, many balanced literacy classrooms hold fast to the belief that all children learn to read differently, and still deploy instructional strategies that are not backed by research. Some prompt young children to use pictures or guess at unfamiliar words based on the context, which can discourage them from sounding out the words they see.

They also ask teachers to divide students into skill-level groups — often based on unreliable reading tests — and give them a wide range of unrelated texts rather than ones that build upon each other and expose kids to more complex language. The weakest readers, those who urgently need to expand their vocabularies and background knowledge, get the most babyish texts with the least academic value.

Balanced

Structured

Different reading approaches

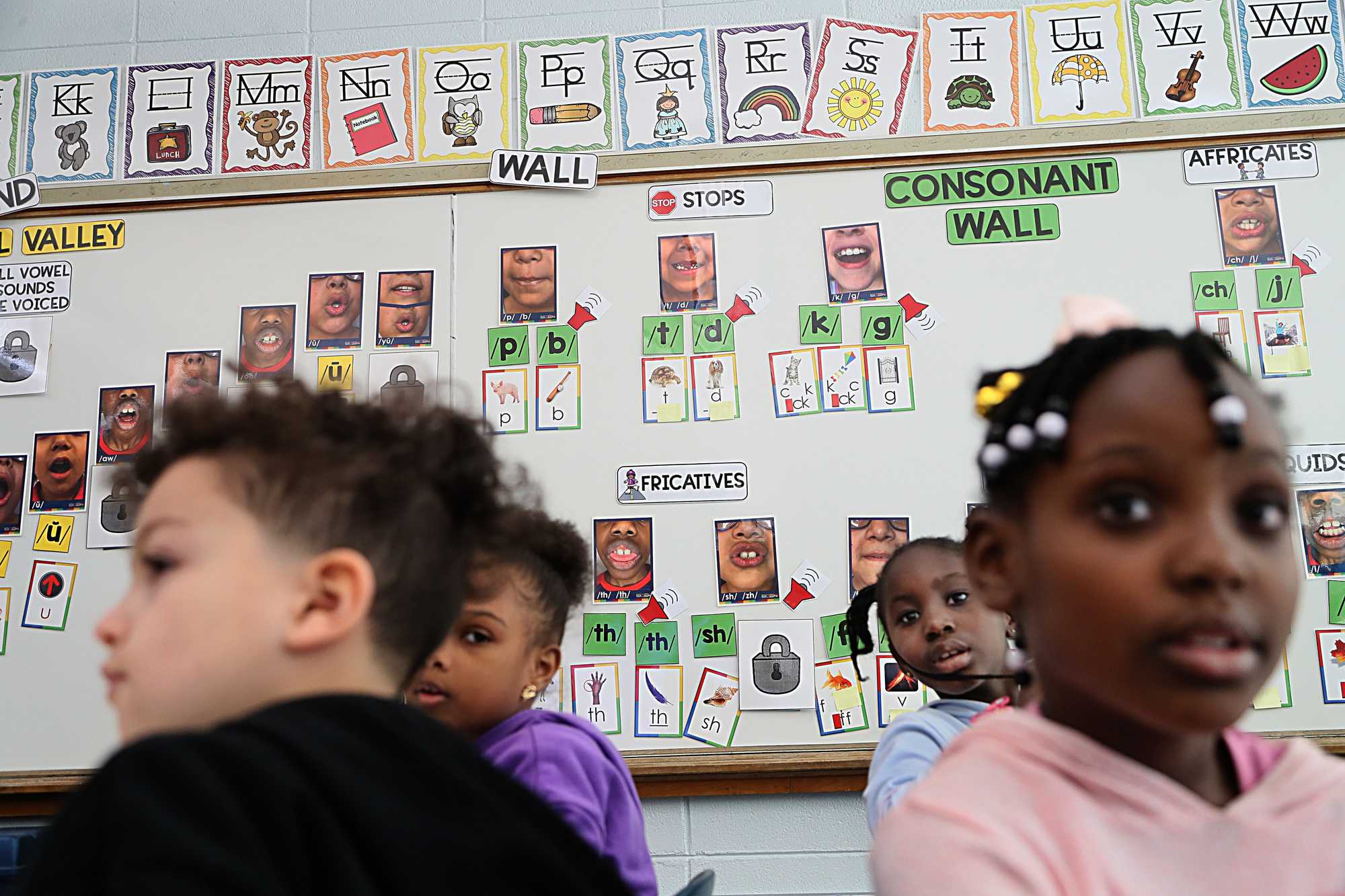

In Massachusetts schools, there are two main approaches for how to teach reading: balanced literacy and structured literacy.

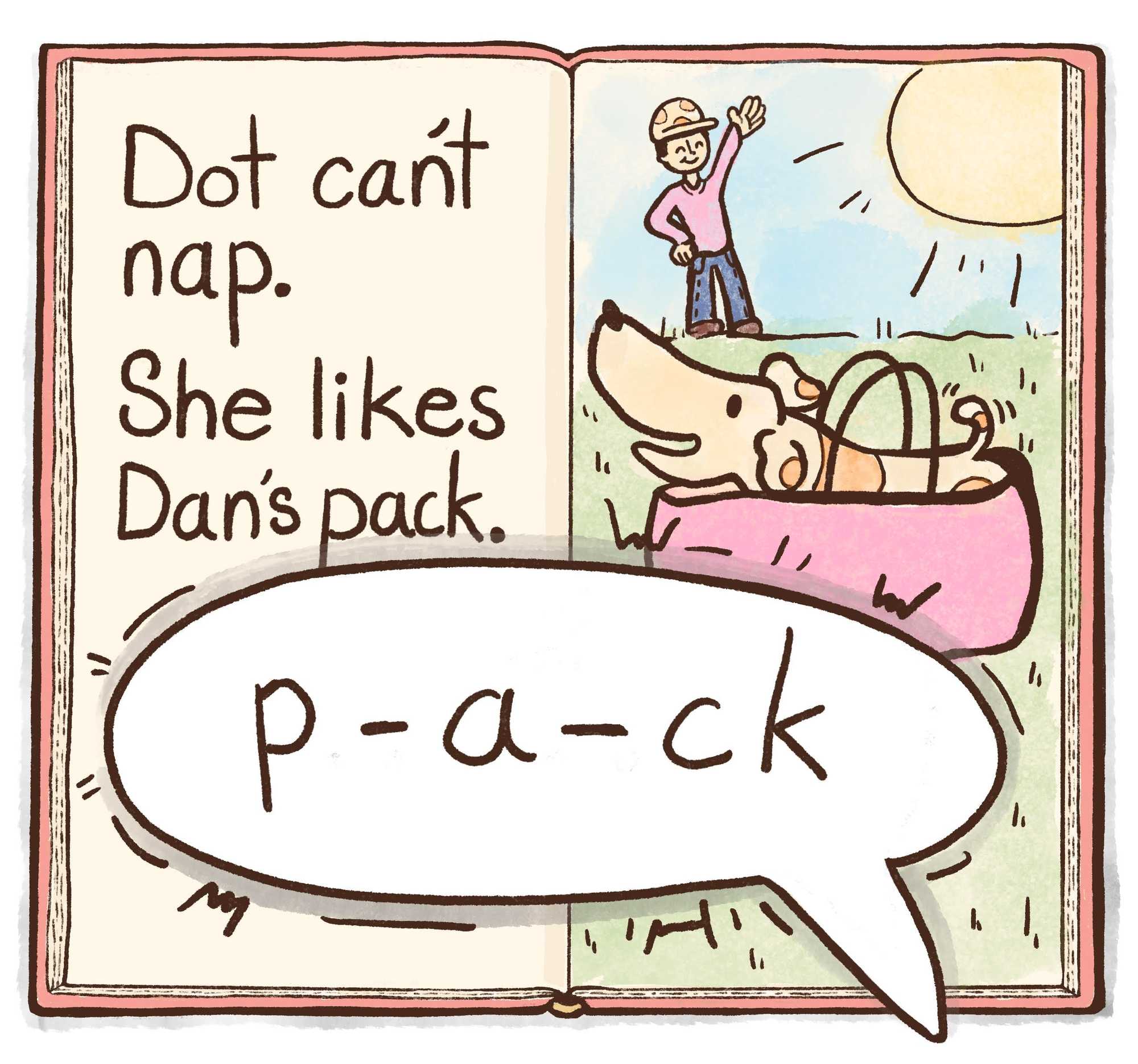

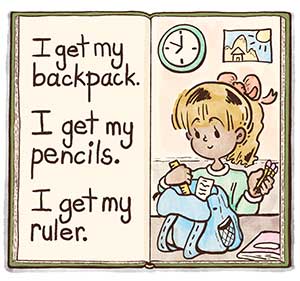

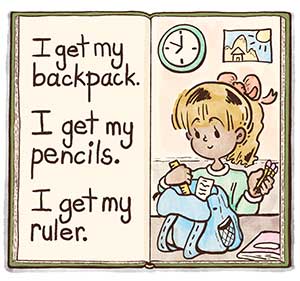

Context versus phonics

Many balanced literacy curriculums encourage kids to use context to figure out unknown words, such as guessing based on a picture. In structured literacy, kids are instructed to use phonics skills to decode, or sound out, unknown words.

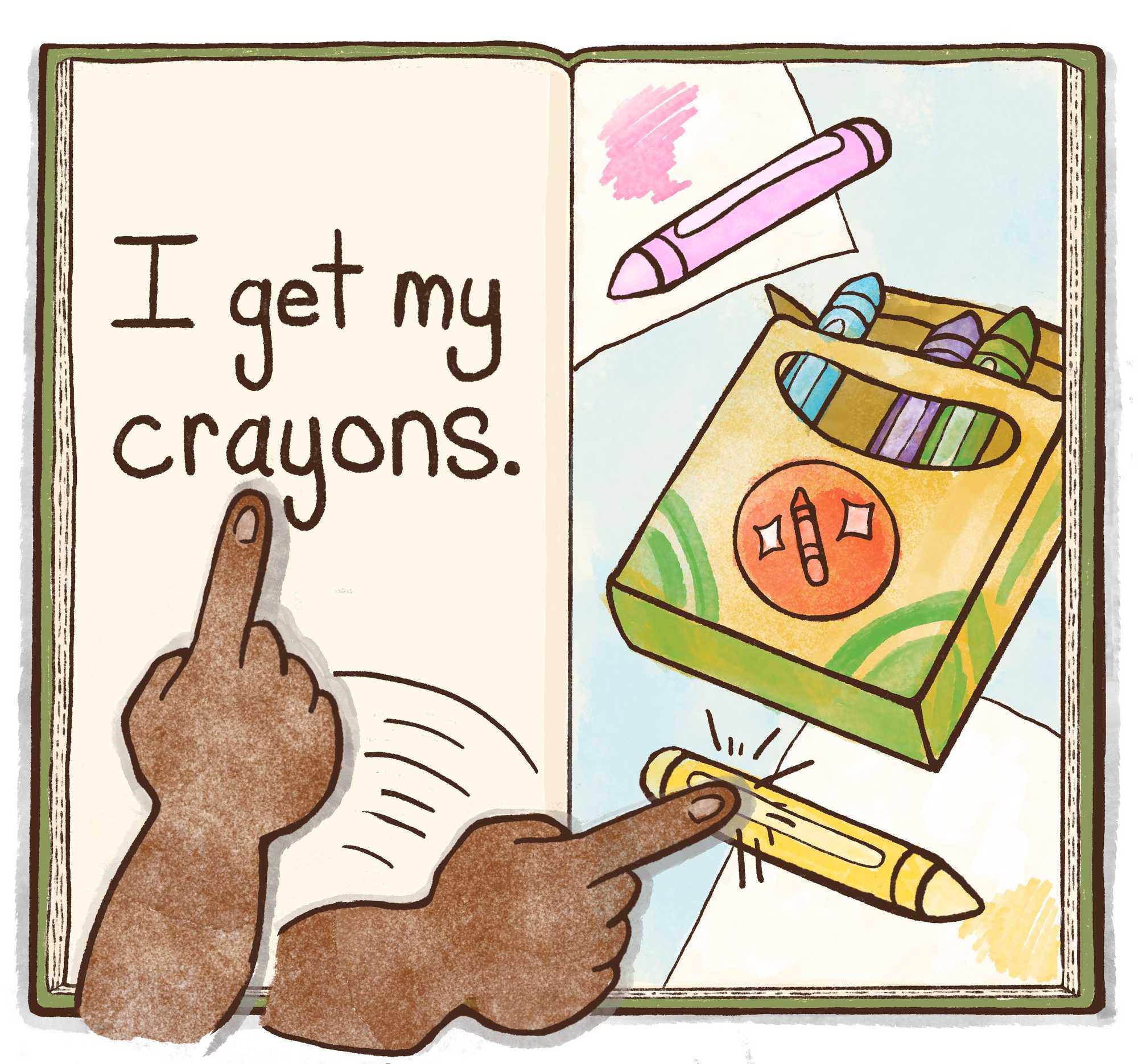

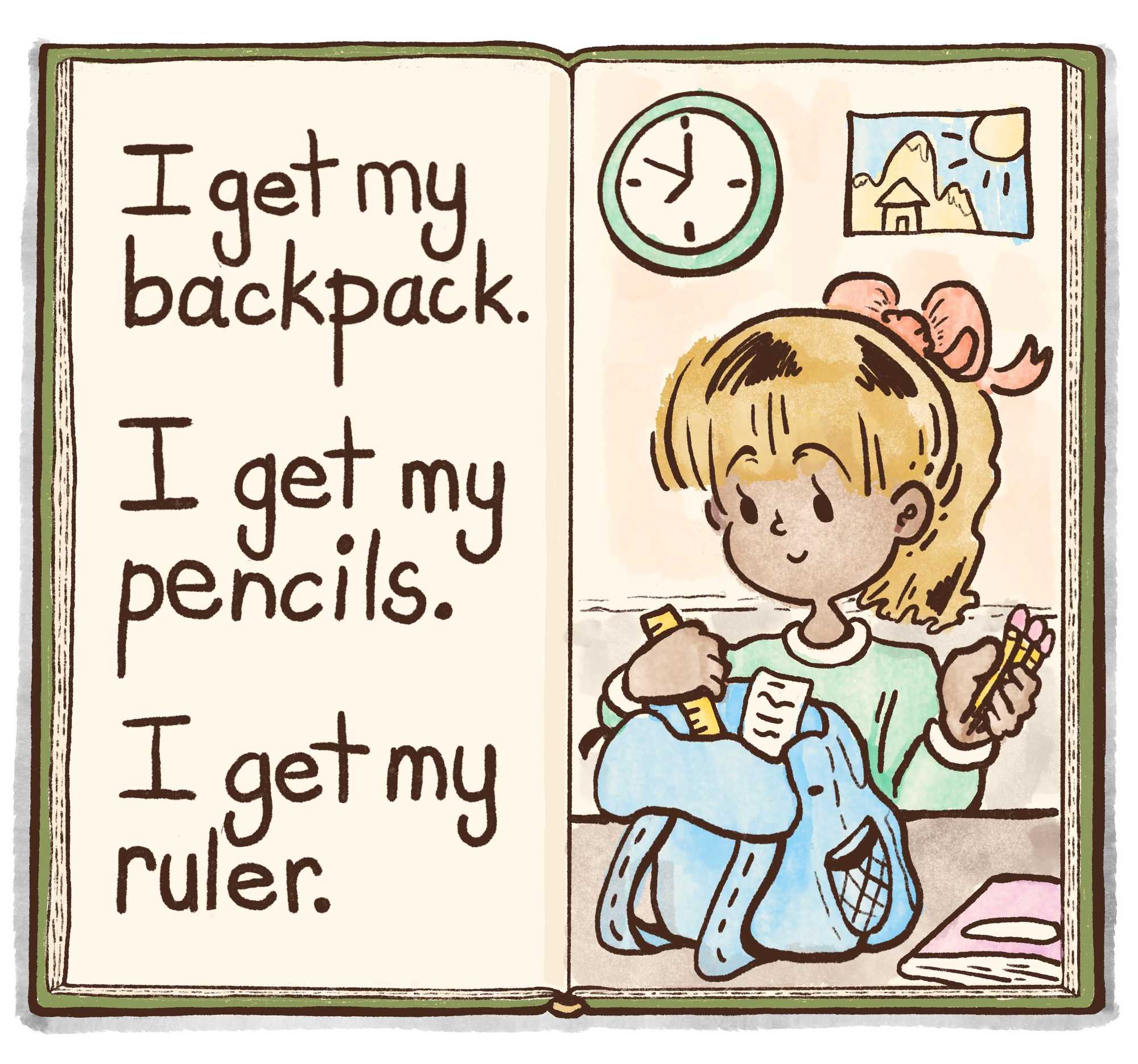

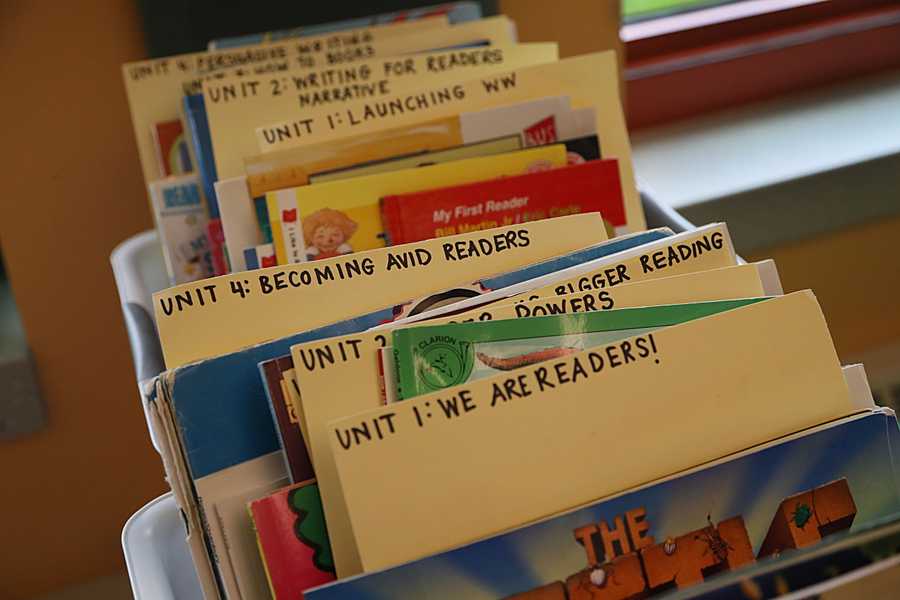

Patterned versus decodable texts

Balanced literacy programs often have patterned, or predictable, texts for early readers. These texts encourage kids to memorize, not decode. In structured literacy, kids practice their phonics skills using decodable texts, which are written for this explicit purpose.

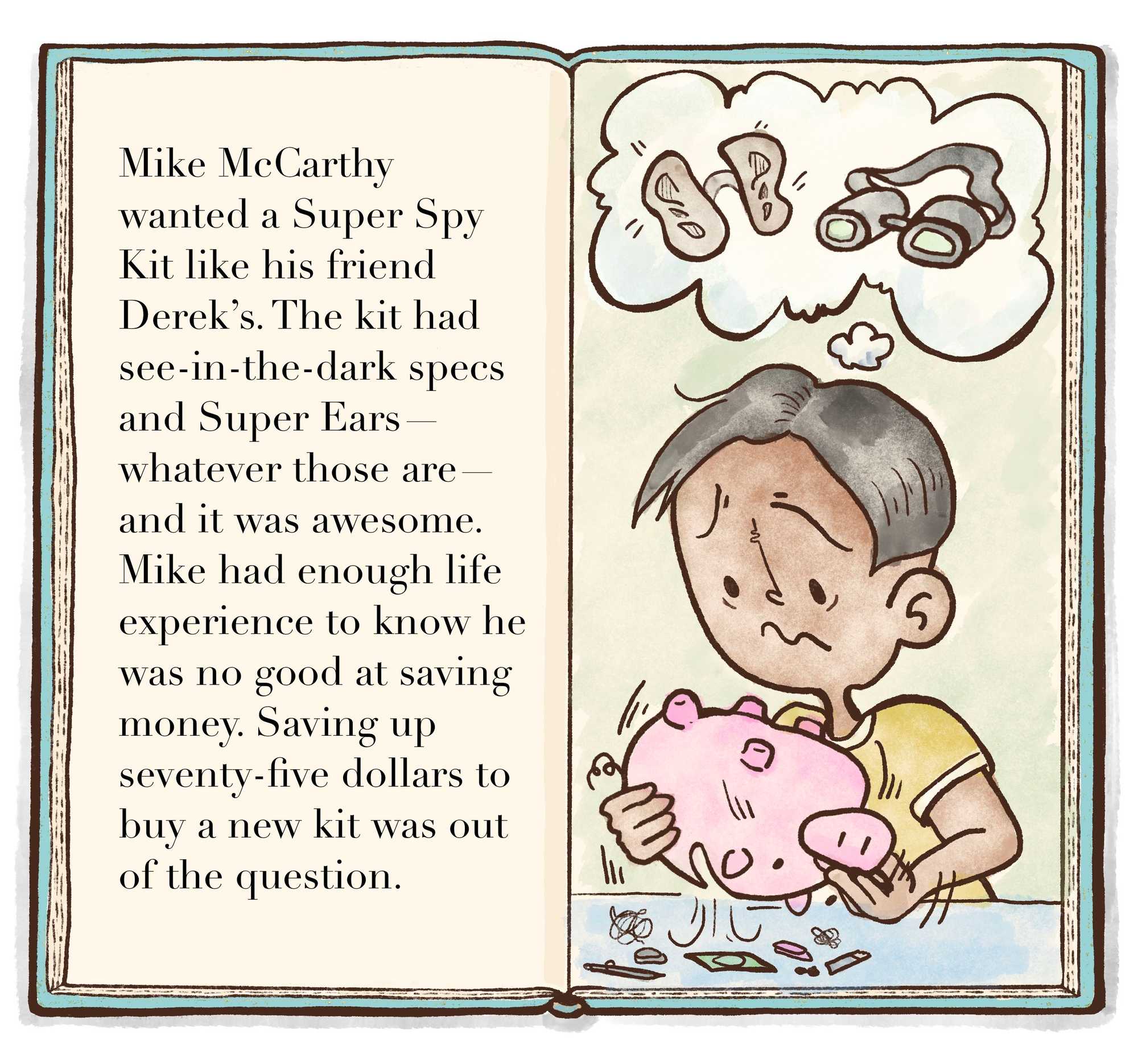

Leveled versus complex books

Balanced literacy often groups kids into reading levels. Kids then read “just right” books — not too easy, but also not too challenging. In structured literacy, the whole class reads complex, grade-level texts, which exposes them to rich vocabulary, grammar, and syntax.

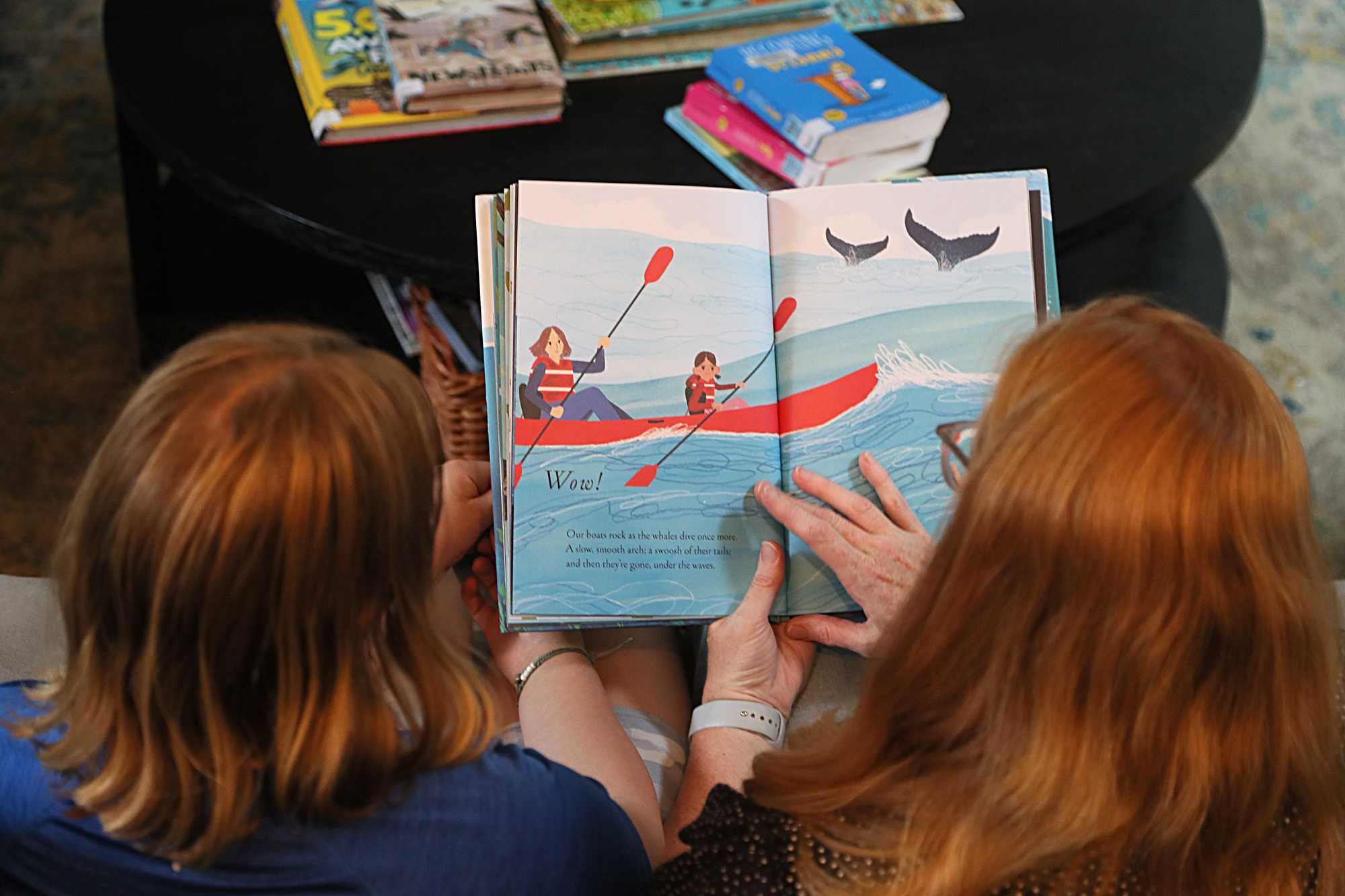

Illustrations by Ally Rzesa, Globe Staff, and adapted from Maria Goes to School, by Susan Hartley; Dot and Dan, by Laura Appleton-Smith; Who Likes Lemonade, by Karen Mockler; and Galileo’s Starry Night, by Kelly Terwilliger.

Brent Conway is assistant superintendent for the Pentucket Regional School District, a relatively advantaged system serving 2,200 students near the New Hampshire border.

Conway, who oversaw an overhaul of the district’s literacy instruction that led to significant improvements in test scores — the district’s statewide English-language arts ranking rose from 245th to 119th between 2017 and 2023 — said merely adding phonics lessons to balanced literacy materials isn’t good enough.

“Like dieting, right? If I cut out the sodas, clearly my health is going to be a little better,” he said. “But if I’m still eating a cheeseburger every night, it ain’t going to be that much better.”

The structured approach that relies on phonics and challenging texts is especially important for students with learning disabilities, those still learning English, and kids from disadvantaged backgrounds who’ve had less exposure to rich language and text.

Left: Balanced literacy materials in the kindergarten class at the Dr. Thomas J. Curran Early Childhood Education Center in Dedham. Right: A book vending machine at Donovan Elementary in Randolph. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

But kids from all different socioeconomic backgrounds need instruction that works, as Brookline dad Ben Kelley, a small business owner, knows. As a first-grader in a Brookline public school, his daughter struggled. In her balanced literacy classroom, she wasn’t getting the high dose of phonics she needed.

So Kelley bought the phonics-focused book “Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons,” and, with his wife, successfully taught the girl at home. He knows not every parent can do the same, though, and it’s made him an outspoken advocate for structured literacy.

“If your school district can’t teach kids to read, then anything else they do is almost meaningless,” Kelley said.

Back in Lowell, Gardenia Osorio isn’t familiar with different types of reading instruction, or the brain research it draws on. She trusts her son’s school knows what it’s doing. Isaac’s father died six years ago, and she’s trying to do her best.

“I’m trying to work, I’m trying to pay my bills, I’m trying to make sure my son learns in school, I’m trying to come home, cook, clean, you know, do all these things,” she said.

“I’m not a teacher. I’m just going by what [school staff] are telling me.”

Marci Amorim, a veteran teacher in Randolph, once went by what she was told, too. She taught using the balanced literacy approach. And she wondered why so many of her students were struggling.

Her classroom walls were adorned with colorful posters of Skippy the Frog, who encouraged young readers to skip words they didn’t know, and Eagle Eye, who nudged kids to make a guess based on the pictures they saw. When her district began the transition to structured literacy a few years ago, she realized that she’d once assumed some students just didn’t have the aptitude to become strong readers.

“I was guilty of this myself for years,” said Amorim, a reading specialist with 21 years of teaching experience. “We’d say, ‘Poor little Timmy is just low [in reading]. We’ve tried all these things, but he’s just not reading. He’s just always going to be low and struggling.’ And no. We just weren’t teaching little Timmy how he needed to be taught.”

The new posters Amorim uses say things like: “Look at the word. Look through the whole word. Read the sounds….”

Rather than picture books with predictable word patterns, which can encourage guessing, Amorim now gives kids texts that let them practice phonics skills. Across Randolph, skill-leveled reading groups are out; instead, kids read about things like fossils and pollinators together as a class, learning new words and expanding their understanding of the world along the way.

Nine-year-old Randolph student Yezlinet Arias put some of that new understanding to work as she toiled away one morning last spring planning a pollinator garden for her school’s courtyard. She thought a penstemon plant would lure in bees — something she had learned about through her extensive reading.

“If we didn’t have any bees, then we won’t have any food,” Yezlinet said.

Randolph paid for its new reading curriculum with a grant from the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, which has taken an unequivocal stand on the merits of structured literacy. As part of its Mass Literacy campaign, the department procured $20 million in federal grant money and now offers districts up to $200,000 to trash their balanced literacy curriculums and buy new materials. Governor Maura Healey’s administration, which declined to make its education secretary or commissioner available for interviews, released a statement pledging commitment to evidence-based reading strategies.

But the grants aren’t big enough to fuel rapid progress, many observers say, especially given the profound disruption the pandemic caused. There also remain many holdout districts: Of the 263 noncharter Massachusetts districts for which the Globe obtained data, 123, or 47 percent, used a curriculum last year the state education department describes as low quality because it includes discredited balanced literacy strategies. More than 100,000 children in grades K-3 attended classes in those districts.

Advertisement

Part of the problem is that there’s only so much money. In most cases, $200,000 doesn’t cover everything districts need to make the curriculum swap.

Some districts can’t even get their hands on those grants. Teachers in Dedham, which applied but lost out to other districts, made do with discredited teaching materials last year, working around their deficiencies as much as they could, despite the desire to dump them and start anew.

Dedham, like many districts, now faces a financial cliff as COVID relief funding disappears. New materials and training for teachers will come at a “tremendous cost,” said Heather Smith, who oversees curriculum for the district.

“We’re in this situation where we’re saying, how are we going to get this done?” Smith said.

Other districts, however, don’t want to change.

The Legislature is now considering a literacy bill that would require districts to use high-quality structured literacy curriculums approved by the state, but it is facing fierce resistance from unions and some school officials. Max Page, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, called the legislation “a flawed, one-size-fits-all approach to a complex task.”

The literacy coordinator for the Lowell Public Schools testified against the proposal at a June hearing.

“This bill, if passed, will reveal the negative impacts on learning when mandates and legislation tell individual districts what to do . . . instead of relying on the expertise in our districts,” Melissa Newell told lawmakers.

Lowell schools use a curriculum that is on the state’s “low quality” list. In 2023, just a quarter of Lowell students met MCAS reading expectations in the third grade.

“We’re in this situation where we’re saying, how are we going to get this done?”—Heather Smith, curriculum director for Dedham Public Schools

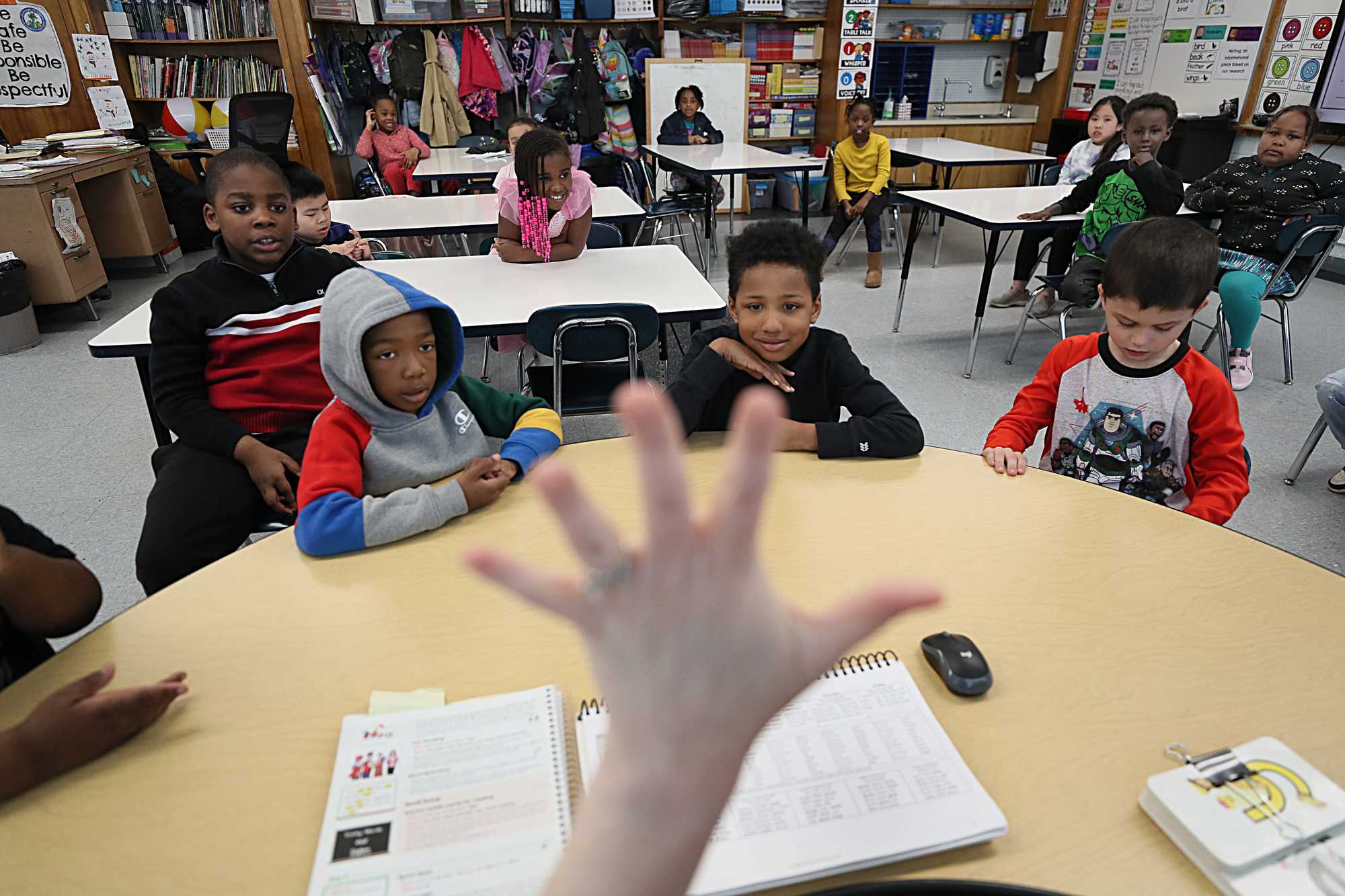

In an interview, Newell said the district’s teachers are trained in evidence-based instructional methods, and have added comprehensive phonics lessons, but the curriculum they use allows teachers to choose culturally appropriate books that reflect Lowell’s diverse population. She attributed the poor scores to poverty and pandemic disruption, and said the district’s internal assessments show kids are making good progress.

“Why,” she said, “would I switch to something that I don’t even know if it’s going to help my students?”

Even though researchers have not studied which brands of the new curriculums work better than others, those favored by the state are grounded in science of reading principles, which are backed by robust research.

The Mohawk Trail Regional School District, in the eastern shadow of the Berkshires, won $400,000 in grants to retrain teachers and switch to K-8 reading lessons that put rigorous texts in kids’ hands. Last spring, fifth-grader Jared Lanoue said his class had recently finished reading a book about Jackie Robinson.

“I like reading. That’s fun,” Jared said, his cinnamon red hair tucked under a trucker hat. “Most of the books have been interesting and give a lot of facts about real stuff that is happening.”

Jared’s mother said she’s seen explosive growth in her son’s love of reading. When the family left for vacation this summer, Jared grabbed a book to take along, something he wouldn’t have done before, Jenni Lanoue said.

Literacy coach Valerie Vasti hears stories like this across the Mohawk district. It’s a far cry from earlier years when Vasti, a former teacher, felt like she couldn’t reach all of her students, despite extraordinary amounts of work.

It felt like “a Sisyphean task,” she said, “pushing the rock uphill every day . . . but not getting anywhere.”

Beyond resistance to adopting a reading curriculum known to work, many districts in the state also lag badly when it comes to detecting and addressing a common reading disability — dyslexia.

The tears in Ali Lynch’s 11-year-old daughter’s eyes are testimony to that.

Claire came home from school one day this spring feeling disconsolate and dejected. She’d been assigned to read “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” C.S. Lewis’s classic novel for young readers and, unlike most of her classmates, she simply couldn’t do it.

Lynch was heartsick but not surprised; her daughter’s dyslexia had long gone undetected, and now, like many of the children in Massachusetts with the language processing disorder — 5 to 20 percent of all children, estimates vary widely — she was scrambling to catch up. Even before the pandemic, just 16 percent of children with disabilities in grades 3-8 met the state’s bar for reading proficiency. Like Claire, these are mainly children who are up to the work but need the right help.

As a preschooler, Claire loved to curl up next to her parents and listen to them read aloud to her; the Judy Moody series was a big favorite then. Independent reading, though, was a terrible struggle, from kindergarten on.

Lynch pleaded with her daughter’s Lexington elementary school for help. At home, Claire’s anxiety over reading and writing spilled out in heaving sobs. By fifth grade, she depended on audiobooks and voice-activated writing software, accommodations her school offered her instead of the intensive immersion in phonics she needed.

This spring, her school finally concluded Claire had a reading disability, but only after Lynch paid $2,850 for an outside evaluation and confronted school leadership with the results.

Advertisement

“I knew there was a disconnect between what she was able to do at school and how smart she is,” Lynch said. “I couldn’t have told you that was dyslexia.”

Lexington Public Schools said it uses a variety of assessments, including a state-approved screener, to identify struggling readers, and Superintendent Julie Hackett said the district is “committed to providing each student what they need to be successful.”

In 2010, before Claire was born, Harvard University researchers published a report that could have changed her life — if it had been acted on promptly. It warned of an entrenched “cycle of academic failure” if Massachusetts did not get better at teaching kids to read. There was no silver bullet, but there were plenty of sensible strategies to pursue, the report said.

“The gap between what we knew then and what we were doing was staggering,” said Nonie Lesaux, a Harvard literacy professor who authored the 2010 report.

A key recommendation: Every student in preschool through Grade 3 should be screened regularly for reading disabilities.

The report sounded an alarm on Beacon Hill, and in 2012, when Claire was a baby, Massachusetts passed a law targeting third grade reading proficiency. Governor Deval Patrick signed it in the library of a Stoneham elementary school, flanked by leading Democratic lawmakers. It created a panel of experts who were supposed to recommend strategies for attacking the early literacy problem from five different angles: early screening for reading problems, teacher training, curriculum, instruction, and family involvement.

It sounded bold and promising, but the panel had no authority to make changes and no political champion. The panel’s work ended in 2019. It ultimately issued five reports; its principal recommendation was that early screening was essential.

“We definitely raised awareness and scared everybody” with the 2010 Harvard report, said Amy O’Leary of the Boston-based advocacy group Strategies for Children, which commissioned the report. “But when it came to solutions, we never implemented (them).”

Advocates for an enhanced response to dyslexia, meanwhile, were fighting their own determined battle to strengthen services for kids with reading disabilities. In 2018, after years of lobbying, the Legislature approved a bill that led to a regulation requiring all school districts to repeatedly check students in grades K-3 for reading problems using a state-approved test. Many already were doing some early screening but not always using a reliable test or testing regularly.

That rule finally took effect this school year — an astounding 13 years after the Harvard report — as Claire began middle school.

“It is frustrating to see that it took over a decade for the one significant recommendation issued by the panel, annual screenings for K-3 students, to go into effect,” said Representative Alice Peisch, the assistant House majority leader, who co-chaired the Joint Committee on Education when the 2012 law passed.

The long-delayed change came only after an exhausting fight: Unions and other critics argued that early screening requirements would lead to too much testing for teachers to administer and students to endure, said Peyser, education secretary from 2015 to 2023.

“We definitely raised awareness and scared everybody. But when it came to solutions, we never implemented (them).”—Amy O'Leary, Strategies for Children

There was a “suspicion that this is just like a camel’s nose under the tent for extending MCAS down to kindergarten,” Peyser recalled.

Some administrators, meanwhile, balked at the higher costs districts would incur when more children were identified as needing special education.

Claire is now getting extra support at school; Lynch has also hired a private tutor, and she’s paid for her daughter to see a therapist as well. Claire’s anxiety around reading has caused her to develop what may be selective mutism, according to the neuropsychological evaluation underwritten by her concerned parents.

“She’s felt stupid, she’s felt inadequate, she’s felt like a failure for so long, and so she protects herself by not talking,” Lynch said.

Dwayne Nuñez understands the implications of the state’s failure to react forcefully to this literacy crisis. Now 41, he grew up in the Boston Public Schools, where, he says, his teachers never taught him to sound out words. Thanks to a strong memory and an outgoing personality, Nuñez made it to UMass Boston, but as a college student, he often suffered the humiliation of having to ask for help with a word while reading aloud in class.

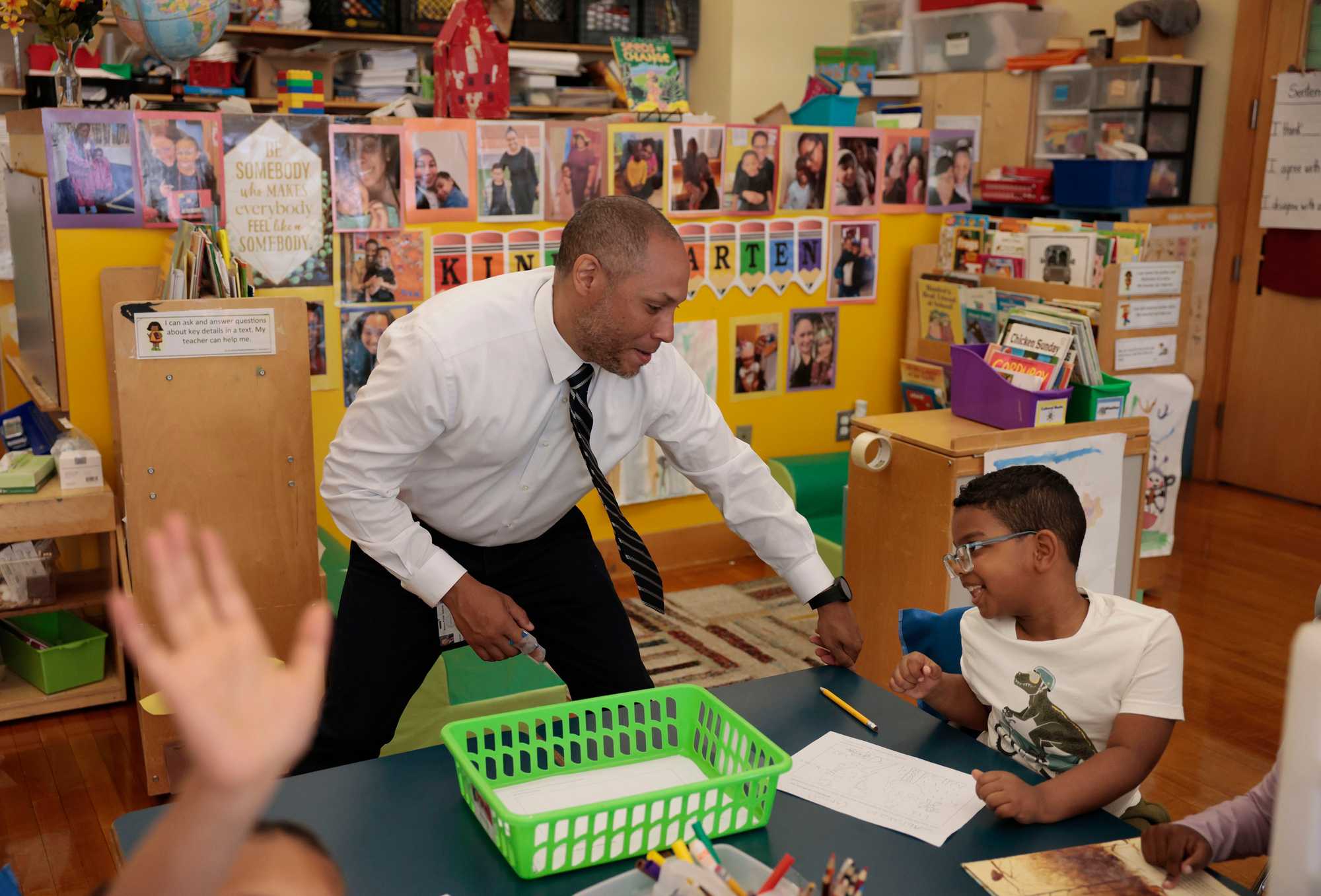

Nuñez didn’t fully learn to read until he started teaching kindergarten and first grade. His teacher training program never taught him how to teach phonics. He put in extra work to learn this skill on his own, and he finally discovered what he’d been missing all these years.

Now an elementary school principal in Boston, he sees himself in the district’s dismal reading scores, especially those for Black and Latino kids. Less than 20 percent of children in those groups passed state reading tests last spring.

“Even to this day, I get this trauma around reading out loud,” he said. “I want to make sure that kids don’t experience what I experienced.”

As a literacy specialist who trained teachers in the science of reading for Boston Public Schools last year, he would carry tissues into tearful conversations with veteran teachers, some of whom were scared of trying something new, fearing the shift would do more harm than good. Others had regrets for using instructional methods deemed ineffective.

“I had one teacher who actually verbalized it and said, ‘I have been doing kids a disservice for 20-something years,’” Nuñez said.

With teachers who resist, he is understanding, but only to a degree.

“I can come off as very pushy,” he said. “I have high expectations, because this is real for me. These kids mean a lot to me.”

Boston, like the state’s other two largest districts, Worcester and Springfield, is in the process of a massive transformation of its literacy instruction, which will require teachers to be trained in the science of reading. The state education department has created remedial online courses for working teachers, but landing a spot is competitive. Some districts, like Boston, shoulder the cost, spending $600,000 on literacy training for its educators.

It’s a price that will have to be paid for years, because even newly minted teachers don’t always arrive knowing about structured literacy. The National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, ranked Massachusetts in the bottom half of the nation in preparing educators to teach reading. Some of the state’s largest teaching colleges received Ds and Fs for not spending enough time on foundational reading skills, according to the council’s syllabus review. The state, through changes in teacher licensing and course standards, is trying to force the colleges to do better.

After deciding to switch careers in her late 40s, Laura London attended one of the state’s most prominent teacher training programs, at Cambridge-based Lesley University, graduating in 2015. While taking classes for her $30,000 master’s degree in special education, London felt she was missing something crucial.

“Like, wait a minute, when are they actually going to teach me how to teach kids to read?” recalled London.

So she shelled out another couple thousand dollars to become certified in a structured phonics program before taking a full-time teaching job in Brookline. She doesn’t think new teachers, entering the profession in their 20s, should have to follow in her footsteps.

A spokesperson for Lesley said the university equips teachers with a “variety of tools to help children learn to read,” including phonics. Lesley’s head of education, Stephanie Spadorcia, said that since 2018, coursework for special education candidates has been revised to focus more on foundational reading skills.

It was Andrew Boucher’s first week of high school, and his legs were still pocked with scratched bug bites, a reminder of a summer that had come and gone too soon. In between helping his mom look after his three younger siblings, he had spent a week at Worcester Polytechnic Institute learning computer programming. His dream of designing video games was starting to feel within reach.

Though Andrew, 14, is exceptionally bright, he has a challenging path ahead. Testing for certain critical reading skills found him worse off than 90 percent of children his age, according to an outside evaluation his mother secured last year.

Top: Tashena Marie sat with her son, Andrew Boucher, in their North Brookfield home. Bottom left: Andrew Boucher (center), 14, swung in his backyard after school with his siblings, Austin (left) and Raymond. Bottom right: Marie watched her children play in their backyard. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Andrew’s school district, tiny North Brookfield, a system of about 450 students, uses two of the reading curriculums Massachusetts considers low quality. The district is shifting to a new structured literacy curriculum, but it can only afford to do so one grade level at a time. Without additional state support, it will take the district years to complete the transition, school officials said.

Andrew doesn’t know what curriculum his teachers used when he was young. He only remembers being asked to pick a book and read — as if it would all just click. It never did.

He worries about his younger brothers. Austin will be starting kindergarten next year, and Raymond, a second-grader, is already grappling with reading difficulties. Reading is a “huge part of life that you need to know,” said Andrew.

He’s counting on the grown-ups who run the schools to do better. It seems simple enough to him.

“Just find the right way” to teach reading, he said. “And do it.”

The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide. Sign up to receive our newsletter, and send ideas and tips to [email protected].

© 2023 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC