A decade after the Marathon bombing, reflection and renewal

It was a perfect spring afternoon 10 years ago when two young men dropped homemade bombs amid the Marathon throng and history swerved. Five lives were lost; many more, changed. A new story for an old town, built of sorrow and resolve, with still no finish line in sight.

TEMPLE, Texas — It’s mid-afternoon at a Mexican chain restaurant. The guy at the next table settles in for lunch with a pistol conspicuously strapped high on his hip. “There’s something you don’t see in Massachusetts,” Marc Fucarile says with a grin.

Here outside Austin, where Fucarile lives about half the time, an armed diner enjoying a fajita is part of the tableau.

Gray patches are pushing into Fucarile’s short brown beard. The Stoneham native and Marathon bombing survivor is now 44. Ten years after the bombing, he walks with a little dipsy-do in his gait. His prosthetic right leg fits around the rounded bit of what’s left of his thigh. “My stump,” he calls it. He’s not delicate about getting his leg blown off. His other leg is a quilt of scars. There is constant dull pain in his surviving leg and phantom pain in the one he lost.

He’s a talker, ebullient, one story flowing into another. Over his T-shirt he wears a 1-inch cross on a neck chain, a gift from his wife, Niki. Fucarile has become more religious since the bombing. He sees God’s fingerprints everywhere. “He literally puts people in my life and it’s undeniable,” he says.

People like Niki Browder. They met through Fucarile’s social media posts about his volunteer work with people with missing limbs. Niki, 41, was born without arms and one leg. At lunch, Fucarile feeds her a forkful of tamale, and then lovingly sweeps a wandering lock of hair from her face.

A decade ago, Fucarile was a roofer with aspirations of getting a real estate license. That became his phantom life.

The bombing on April 15, 2013, propelled him into a different world, one filled with people he otherwise never would have met, or, in one special case, fallen in love with.

It is not too much to say the Boston Marathon bombing and subsequent manhunt changed everyone touched by it. Those most profoundly affected will spend the rest of their lives mourning those taken from them, or a lifetime living with injured bodies that may have scarred over but will never be the same.

Their lives were abruptly rerouted; some are still finding their way.

For those not physically harmed by the blasts, the lingering effects are subtler, but still profound. The trauma reordered the way they look at the world and their own part in it. It propelled people off in new, uncertain directions.

What also becomes clear now, in a moment of reflection after 10 years, is that time gives contours to our pain and grief. Some deeply affected by the bombing didn’t want to speak at all at this anniversary, and, in fact, are dreading it. For others, though, time unlocks doors to conversations that wouldn’t have, couldn’t have happened 10 years ago, revealing pain and vulnerability that diverge from the “Boston Strong” narrative of resilience, strength, and goodwill.

Fucarile’s new road is as an evangelist for people with mobility impairments. It is his life’s work. It dates to when he woke in the hospital to the overwhelming generosity of the community. “I was famous, in a sense,” he says. “People were calling, trying to help. Most people who lose a limb don’t get that kind of help. I realized that fast.”

He sees fixable problems everywhere: Doors too narrow for wheelchairs, handicapped parking spaces too close together. He rattles off organizations for which he has volunteered or raised money, such as Camp No Limits, for kids with missing limbs and limb differences. His phone is full of photos of children in wheelchairs or with prosthetics, skiing or shooting baskets. “I think there might be one leg in this whole group,” he says of one photo of a handful of grinning kids.

Fucarile’s son, Gavin, was 5 when Marc was injured. He’s 15 now. A year after the bombing, Fucarile married Gavin’s mother. They were desperate to give their boy stability. A year later they were headed for divorce.

Fucarile swore off marriage forever. So he thought.

He first met Niki in person in October 2018. She’s a Texan, born and raised. When he had plans to be in the state for a celebrity softball game, he invited her. She came with a friend.

“When I met him I wasn’t looking for anyone,” Niki says. “I had just gotten out of a relationship. I had almost canceled on him.”

Fucarile had seen Niki’s picture online but was not prepared for seeing her in person.

“She lit up the room,” he says. “I was taken aback by how beautiful she was.”

‘I was put through a big shock to the system’

Dic Donohue is a trim guy with a youthful vibe who laughs a lot, as if laughter is punctuation. He’s joking about balky hips and pulled muscles.

“I try to stay active and do stuff, but I’m getting old,” he says.

Old? Come on, man, you’re 43.

“But inside I’m like 107, you know?” he says. “I was put through a big shock to the system.” He laughs.

Ten years ago, Donohue, then a transit police officer, passed about as close to death as medically possible while managing to survive, after being shot in the right femoral artery during the chaotic gun battle with the Marathon bombers in Watertown on April 19. The date is memorialized on Donohue’s shoulder, in an edgy tattoo of the Grim Reaper, marking the moment he escaped the grave and his life was irrevocably changed.

There is a long surgical scar on his right thigh where the bullet entered. He’s got scars on his left leg, too, where surgeons harvested veins to repair his damaged artery. His left leg hurts all the time and occasionally fails him, sending him slipping down the stairs. He was a runner once but can’t really do that anymore, not without days of pain.

“It is what it is,” he says. “I live with it — I hung up the track spikes, so to speak.”

He had thought everything would just go back to the way it was. But that was wrong, on several counts.

After it was clear he would survive, Donohue went hard at returning to work. It took two years of rehab to get back. It took less time to recognize he no longer belonged. With his injuries, many of the physical demands of the job were out of reach. He couldn’t do hours on his feet. Even worse, what might happen if a fellow officer in an emergency needed him here and now, and Donohue couldn’t get there?

“I felt like I had failed,” Donohue says. Making peace with the loss of his policing career was tough. It took perhaps a hundred conversations with family, colleagues, his former chief, and deputy chief. “They’re all like, ‘Look where you came from. You made it back. You made it back for a minute, a day — you did it.’ And, eventually, you just gotta settle with that and be proud.”

Donohue’s wife, Kim, recalls those difficult days. “We realized, whatever road we were on before, it was gone,” she says. “We had to find road B. Being a police officer was his dream. So what’s the next dream?”

Donohue threw himself back into school, pursuing a Ph.D. in criminology and criminal justice from the University of Massachusetts Lowell. He graduated in 2019.

Today, Donohue is a policy researcher at the RAND Corporation, a global think tank, where he works on homeland security and law enforcement issues. It is meaningful work on topics important to him. The couple had two more sons after Dic Donohue was wounded, and now have three boys. Their suburban home north of Boston is packed with enough hockey and lacrosse equipment to stock a used sporting goods store.

“Do I think about it every day?” he asks himself. “No. I don’t think about 10 years ago every single day. I can’t dwell on what happened in April 2013 for the rest of my life. ... Um — my leg hurts.”

He laughs but there is no joke in sight. “I know when I wake up in the morning until the minute I go to sleep, my leg is going to hurt. I know that. But it’s just life.”

A fifth life lost

A parting sequence at the end of the 2016 film “Patriots Day” is seared in the mind of Nicole Simmonds-Jordan.

The series of photos commemorate those who died in the terror spree. First, Krystle Campbell, then Lingzi Lu, then Sean Collier, and then Martin Richard. The screen fades to a dedication page. And then the credits roll.

No mention of her brother, a Boston Police officer named Dennis “DJ” Simmonds, who died of a brain aneurysm a year after one of the attackers’ homemade pipe bombs exploded near his head during the firefight in Watertown. He was 28. A state panel recognized his passing as a line-of-duty death, citing his persistent injuries from the shootout.

But getting the rest of the city to acknowledge Simmonds as the fifth life lost hasn’t been as easy. It’s become something of a full-time job for his sister, an executive director at Morgan Stanley, by day. The blockbuster film — directed by Peter Berg of “Friday Night Lights” fame and starring Boston icon Mark Wahlberg — documents and celebrates law enforcement efforts that week but does not mention Simmonds. During the press tour, the film’s producers and stars skirted questions about why Simmonds wasn’t acknowledged in the credits or as an influence on the main cop character, who responded on Boylston and in Watertown, just like Simmonds did.

The omission is one of many slights Simmonds-Jordan has felt over the years. While other families of victims and survivors are hounded by the media and swarmed with donations, she finds out most of her information about Marathon-related events through the Collier family.

“It may seem petty, but DJ was a man who took so much pride in being a Boston cop, who called us to say, ‘They will not take our f****** city,’ when the bombs first went off. And for him not to get the recognition he deserves? It hurts,” she says.

Humans are defined as much by their singularity as their mortality. Most struggle for decades before finding which single life they want to live. Some never find it at all. But DJ Simmonds?

Simmonds knew when he was a toddler and went for it with a laser focus. One of his early words, which came sputtering out, was “p-p-police officer.” In high school, he interned with his future employer and came home from a ride-along with fire in his eyes. Next came a degree in criminal justice from Lasell University. Then, the police academy, where he graduated as the youngest in his class.

“He wanted to be the chief of police for Boston one day,” Simmonds-Jordan says. “I mean, he wanted to go all the way to the top.”

On the day of his death, she walked into her brother’s apartment to find a desk strewn with study materials for the sergeant exam, remnants of a dream interrupted.

“Each year on my birthday, I feel a little guilty for outliving my older brother, who knew exactly what he wanted from this world,” she says. “And almost every day, I grieve the life I could have had if there was no Boston Marathon bombing, no shootout in Watertown. If my brother was still alive.”

This is the life Martin could have been living

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — Nolan Cleary is running the Boston Marathon this year, full of that air of invincibility that comes with being 18. He stretches for all of one minute inside his dorm room before setting out for a 20-mile training run. In the pockets of his BC High gym shorts, a set of keys jingle, and a Purdue University student ID card pokes out. His hands are full, one with a water bottle and one with an iPhone, which buzzes every 10 minutes with Snapchat notifications.

Has he considered one of those belted fanny packs strapped around the waist of other runners preparing for the Boston Marathon? He laughs at the very thought of it.

“That would be so embarrassing,” he says. Then his long legs quicken, taking him from a saunter to a jog, and he starts on a loop that will take him through much of West Lafayette.

Ten years have passed since Cleary’s parents called him downstairs to tell him the news that Martin Richard had died. The two had been inseparable growing up, roaming the streets of Dorchester and chasing after one another in flag football. But now that big-eared, gapped-tooth, olive-eyed kid was gone. Cleary remembers hearing the words, burying his head in his mother’s chest and crying, but still not really grasping what had just happened. Eight-year-olds aren’t wired to understand death, especially one so devastatingly out of the natural order of things.

A decade later, Cleary is an adult (albeit a teenage one), who decorates his own room (with thumbtacked flags), devours podcasts (of the Joe Rogan variety), and arranges interviews with outlets like CBS and CNN (though only after 10:30 a.m. on weekends). He’s running the Marathon for the Martin Richard Foundation this year alongside two other childhood friends, Ava O’Brien and Jack Burke. All are eligible to enter this year as freshly minted 18-year-olds. The trio has been speaking to the press for more than half their lives, for two more years than Richard was given.

“It’s like he’s frozen in time,” says Cleary. “It’s strange. I don’t generally talk about that day or Martin. I don’t, like, volunteer it up in conversation with my friends. The only times I ever really discuss it are on television or to a reporter.”

Part of him wonders why the reporters keep calling. He’s just a regular 18-year-old, consumed by 18-year-old things, like navigating his first year of college, missing his hometown, contemplating his major, texting his girlfriend, and plotting a possible semester abroad.

But perhaps it’s this teenage banality that keeps the cameras coming. This is the life Martin could have been living.

By now, Cleary has reached the halfway mark of his 20-mile run. A group of friends beckons him to the nearby quad. He waves back and saunters over, having hardly broken a sweat.

All the inequity made clear

There’s a story trauma surgeon Tracey Dechert didn’t tell the sea of cameras in the ambulance bay of Boston Medical Center in the days after the bombing. But a decade later, as she sits in a shabby, plant-filled office at the start of a 24-hour shift, she’s ready to tell it.

“I recognize that it wasn’t the right time then,” she says. “But now, maybe enough time has passed.”

When she starts, it’s like no time has gone by at all. It spills out of her in starts and stops, little pauses that steel her from being overcome by the torrent of emotion bottled up over the last decade.

The story goes like this: In the wake of the bombing, Dechert’s trauma unit — whose patients include many of the city’s most vulnerable residents — was flooded with an unprecedented burst of donations from anonymous donors. But those dollars came with an asterisk: They were only for the 19 admitted patients injured in the Marathon bombing. There were roughly a dozen other gunshot victims in Dechert’s trauma unit that day. And one of them lost his leg. But because that trauma resulted from bullets rather than shards of shrapnel on Boylston Street, the trays of doughnuts, boxes of coffee, offers for free prosthetics, and procession of celebrities never made it to his bedside. Instead, the man wrestled with his state insurance plan over whether they’d cover his prosthetic limb and physical therapy.

“And that made me really angry. Just because your trauma isn’t a public event, that doesn’t mean it isn’t tragic. It is still awful. It is still life-changing. In real-time, we had this one group of patients who got it all. So much. More than they could even use. And then we had this group of other patients who got no attention, no resources, less everything,” says Dechert.

In the decade since the bombing, Dechert has become surgical trauma chief at BMC, the first woman to head a Level 1 adult trauma center in the state’s history. Not bad for the daughter of a maintenance worker in Pennsylvania’s coal country, the first in her family to complete college.

Like her peers in trauma medicine, she regularly logs 24-hour shifts, doing her best to give the possibility of life to those cut down by violence. Still, some of her patients die, a point made clear each day when she slips into a pair of fading Dansko clogs stained with the blood of a patient stabbed by her own child, a woman whom Dechert couldn’t save. Sometimes, she reasons, it’s good to let the grief and anger loiter if only to fuel the fire for the next day. And still, she and her colleagues don’t say the word “marathon” — for them, it is always the “m-word.” The memory of that day and its aftermath — all the inequity it made clear — festers in her mind, a reminder of how society selectively chooses who is worthy of empathy.

“I still don’t know if people can hear this,” she admits. “It’s not the feel-good story. It doesn’t fit the Boston Strong narrative. But it is the truth.”

‘There is absolutely a world ... where things are a lot more difficult’

Andrew White was 2,500 miles away in Portland, Ore., when one of the bombs exploded outside Marathon Sports, near his entire family. His brother, Kevin, and mother, Mary Jo, were showered with shrapnel. His father, Bill, bled profusely, nearly dying and ultimately losing a leg. White, a clinical psychologist, received the news from his receptionist.

“The Boston Strong narrative was about how the city persevered, and I think that was the right attitude in the moment as far as recovery and resiliency. And I think it was authentic. But it is sort of all-consuming,” recalls White.

Ten years later, just Mary Jo and Andrew White are left. Kevin died from a sudden illness in 2015. And Bill passed last winter from complications related to Alzheimer’s disease. Both had found fraternity and support in the Boston Strong community, which they discussed openly in essays and on camera.

But there were also moments not fit for broadcast, when that strength withered. An agonizing mental health battle for Kevin. The insidious creep of dementia for Bill.

“It’s easy to see the interviews and the smiles and think everyone else must be getting on great. And then if you’re not getting on great, it’s easy to think, well, ‘There must be something wrong with me,’” says Andrew White. “But the good can exist with the bad. There is absolutely a world behind that world where things are a lot more difficult.”

‘You can focus on the loss, or you can focus on the light’

Jimmy Plourde looks like a Boston firefighter straight out of central casting. Buzzed, graying hair. The jaw of a superhero. Broad chested. A megawatt smile. Wise-cracking. Quick-talking.

And right now? Crying.

He blames the tears on a song playing on the speakers of this Roslindale coffee shop. A 2015 bittersweet ballad about Peter Pan called “Lost Boy.”

“That is so weird. I haven’t heard this in years,” says Plourde, brown eyes pooling. The song was playing on the radio as he pulled into the parking lot for the funeral of Victoria McGrath. Three years prior, he’d carried her from the finish line to safety after the bombing. A photograph of the pair — a close-cropped, burly Plourde, grimacing and defiant, and McGrath, blonde with ballet flats and blood-soaked legs — quickly went viral. Initially, Plourde had balked at the idea of visiting McGrath in the hospital. As a rule, he tended to shy away from the individual media attention — “It’s about the ‘we,’ not the ‘me’” — and, like many first responders, preferred to separate his professional dramas from his personal life.

“If I were friends with everyone I met on the job, it’d be too much,” he says. Too much weight. Too many tears.

But, eventually, his wife convinced him to go, and McGrath’s sunny charm and quick wit won him over. The two became like newfound siblings. Their families spent Christmas together. Plourde became McGrath’s self-appointed bodyguard as she endured surgery after surgery — six in all — and the barrage of media attention that came with being a survivor. She did her laundry at Plourde’s house, attended his daughters’ birthday parties, and called him for help when her car was towed.

But in March of 2016, Plourde got a call from McGrath’s father. Victoria had been killed in a car crash while on vacation in Dubai. She was just 23 years old.

It was random, senseless, brutally unfair. Which is why Jimmy Plourde finds himself crying to a pop song in a coffee shop in Roslindale. He is surprised at himself but not embarrassed.

“I’ve learned to appreciate these moments. Maybe it’s the gray hair talking, but you’ve got to take the time to look for the signs. You can chalk something like this up to coincidence, or you can choose to take some value from it.”

The Plourdes and the McGraths, who still spend Christmas together, live by a motto shared by the families of the victims of the Sandy Hook massacre: “You can focus on the loss, or you can focus on the light.”

For years, Jimmy Plourde has been all about the light. He has used his vacation time to build playgrounds across the United States — and one in Rwanda — for a Sandy Hook organization called “Where Angels Play.” He’ll be on the road to southern New Jersey in just a few hours for a build.

McGrath’s parents focus on good works with a similarly dogged — and exhausting — enthusiasm. They’ve poured themselves into acts of service, serving on boards and charities and running a foundation in Victoria’s name. It’s a way to honor their daughter — a zealous philanthropist before and after the bombing — but also, they acknowledge, to stave off the negative thoughts. Of which there are, inevitably, many.

“We’ve felt it all. Abandonment. Sadness. Anger. Shock,” says Jill McGrath. “But we’re not going to let the negative emotions consume us. We’re not going to wallow in grief. If we can make something positive come out of all this, then we have a reason to live.”

Exactly where I want to be

Sometimes life’s road seems so obvious that you don’t exactly choose it, you just stay the course, like a needle in a record groove.

“My original path was super clear cut to me,” says Bobby O’Donnell, a trim 29-year-old, built to run. “I was going to go to college, do four years, go to medical school, be an emergency room doctor, have kids, and that’ll be it. I had it figured out at 18.”

Ten years ago, he had barely ever ventured beyond New England. He was a middle-class kid from Easton who had never really struggled at anything. “And then the Boston Marathon bombing happened.”

He was 0.7 miles from completing his first Boston when the police stopped the race. O’Donnell’s entire family was waiting for him near the finish line. For a brief time, he feared that everyone he loved might be dead.

His family was fine; O’Donnell, however, was not. After the race, he was beset with anxiety. His heart raced at the simple act of lacing his running shoes. He broke into sweats if he went too long without hearing from his parents. To see a bag on the ground brought panic. Counseling didn’t help. “I’d get in this dark spot like, well, what is gonna work and will it ever stop?” he recalls. “And then I had this immense feeling of guilt, like I didn’t have it that bad. Tons of other people lost everything. I didn’t feel like I had the right to be as upset or disturbed as I was.”

What O’Donnell ultimately did to turn his life around was completely out of character. While finishing studies to be a paramedic, in 2015, he accepted a 10-day volunteer opportunity in a rural village in Nicaragua, providing medical training and services. “I normally would never do this,” he says. “The old me wouldn’t have.”

That trip knocked the needle out of the groove. It enabled O’Donnell to create his post-trauma life.

“I met all these people all from around the world and had these very intellectual, thoughtful and meaningful conversations with people who I’d never meet otherwise,” he says. While there, he discovered a deserted beach and set out for a run. “It was this amazing, primitive feeling of running just for the sake of doing something that I loved to do. And I wasn’t thinking about bombs. … And I just had this revelation — there has to be places like this all over the world that I can go and do this.”

Since then, O’Donnell has recast himself as a global hunter of aerobic thrills. He has run marathons on all seven continents, including a penguin-littered course on Antarctica. He has raced throughout the US, in Iceland, England, Scotland, Tanzania, and Nepal. He climbed Mount Kilimanjaro and trekked to Everest Base Camp. In 2018, he through-hiked the Appalachian Trail. He summited all 48 mountains in New Hampshire above 4,000 feet, and all 67 in New England. The 2,600-mile Pacific Crest Trail is on his agenda.

Today, O’Donnell, newly engaged, is a flight paramedic on a med-flight helicopter in Manchester. He serves others and feels useful. “More than a lot of jobs in health care, we get the best opportunity to help sick people every single day,” he says, “because people don’t call a helicopter unless they need a helicopter. And it’s exactly where I want to be.”

A chance to give others hope

In Nicole O’Neil’s case, mental trauma was not an “invisible injury,” as it is often called. It was obvious.

In 2014, ahead of the first anniversary of the Marathon bombing, O’Neil agreed to be interviewed by the Globe about her struggles after the attack. She opened her door to find two reporters when she had anticipated only one. Her eyes went wide with what looked like shock and fright at being confronted by something unexpected, no matter how ordinary.

More conspicuous was the way her right leg involuntarily bounced when she sat, like the needle on a sewing machine. She joked that her leg ought to be super-toned for all that exercise. “The leg was the constant,” she says now. “It became sort of the thing I was known for.”

O’Neil was a race spectator on Marathon day 2013, watching from Boylston Street. The explosions were frighteningly close. She was not physically hurt, but within days a debilitating anxiety took charge, punctuated by panic attacks. And of course, the shaking leg.

She was open about her struggle, even blogging about it. There was no secret trick to get better, just work.

“I hit it from all angles and I think that’s really important,” she says, in an interview at her home, now in Reading. “I saw a trauma specialist at Beth Israel that deals specifically with acts of violence and trauma from violence. There were specific Marathon group support programs that I was participating in. I was lucky to have great support around me, just family and friends.”

The bouncing leg finally went away, some 20 months after the bombing.

In 2016, after the Pulse nightclub shooting in Florida, O’Neil joined a group of Boston Marathon survivors on a trip to Orlando, to speak about the road to recovery with therapists, counselors, and survivors of the attack.

“There was just something really powerful about being able to give them hope,” she says. That feeling stuck. Today, O’Neil, a professional photographer, is making plans to go back to school at age 43. She wants to be a trauma therapist.

An image indelibly linked with the attack

Two years after the bombing, at the 2015 Boston Marathon, a battle unfolded on the streets between two unusually fast octogenarians.

Bill Iffrig went out hard, clocking a zippy 1:56:26 for the first half of the race, taking the lead in the 80-plus age group.

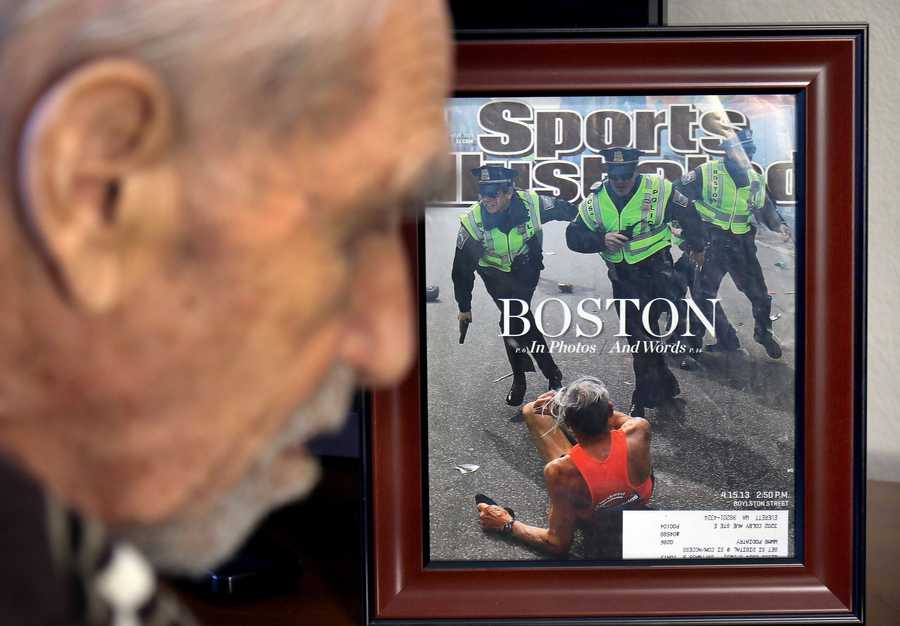

It was Iffrig’s first Boston Marathon since 2013, when he became indelibly linked with the attack. Then 78 and lanky, like an aerobically fit Ichabod Crane, Iffrig was a few strides from the finish when the first bomb exploded. The force turned his legs to noodles, as he later put it, and he collapsed. Globe photographer John Tlumacki captured the famous image of him sprawled at the feet of three police officers. Sports Illustrated would publish the photo on its cover.

Iffrig, from Lake Stevens, Wash., would skip the race in 2014, when he was 79, according to his son, Mark. He wanted to win his age group and figured he’d have a better shot once he graduated from the 75-79 division to 80-plus.

Six minutes behind Iffrig at the halfway point of the 2015 race was Harold Wilson, then 82, from Tyler, Texas. Wilson was a 140-pound, white-haired, road-racing Terminator. In 2013, Wilson was the only runner in the 80-plus group to complete the race before it was stopped, according to official records. “I finished, sat down, had time to pull my shoes off to get my pants on when the bomb went off,” Wilson says, in his soft Texas twang. He recalls waves of people running toward him, faces twisted in terror.

Iffrig led for more than 20 miles in 2015, over Heartbreak Hill, when the bottom fell out. By Kenmore Square, Wilson had the lead. He won the 80-plus group for the third straight time, in 4:18, about five minutes ahead of Iffrig.

In the years since that race, the relentless footsteps of time, still undefeated, have caught up with the two athletes who outran it longer than most.

Wilson is 90. His knees forced him to quit running five years ago. He doesn’t regret using up his cartilage on something he loved. “Two things come with growing old — loss of memory, and I forget what the other one is,” he says. He sells the joke well, but the laughter fades. “I’m pretty healthy now. I know all that can change overnight. You don’t go forever.”

Iffrig, 88, is in memory care. He has largely lost the ability to communicate, but still recognizes family. He’s still him, Mark Iffrig says. The one totem in his room from his running days is a framed copy of that Sports Illustrated cover.

What Iffrig remembers of the bombing is anyone’s guess. But he is happy, according to his son. Perhaps he remembers the cheers, not the smoke, the three cops, or the screams.

‘Even in the most difficult situations, it can get better’

That day in 2018, when bombing survivor Marc Fucarile met Niki in Texas, they had dinner and a couple drinks, and saw a Texas high school football game. It was fun. Then they met for lunch. As Fucarile tells it: “When the waiter asked, ‘Is there anything else I can get you?’ Niki says, ‘Two arms and a leg?’” Fucarile could not stop laughing. “I thought she was just the coolest thing.”

They chatted on the phone just about every day after that, and then met for a dinner date in Austin on New Year’s Eve, at a big, romantic place on Lake Travis. Two years later, Fucarile proposed in the same restaurant. Their perfect day is squeezing onto one big chair together, drinking homemade sweet tea, and watching their shows. “And I’m feeding her popcorn or M&Ms,” he says.

Fucarile spends about half his time in Massachusetts with his son, during which Niki lives with family. Sometimes Fucarile flies between Boston and Austin, other times he drives — doable in 29 hours, if you don’t mind peeing in bottles. The travel is a grind but it’s not forever. Once his son heads to college, Fucarile intends to move to Texas full time. “I want to build a handicapped accessible house geared to all our disabilities,” he says.

Near the end of lunch, Fucarile pulls out his phone to show some more photos. His tone hardens, like things have suddenly gotten real. “My wife doesn’t like these pictures,” he warns.

They are photographs of Fucarile, taken moments after the explosion. He’s on the sidewalk, lying on his side. His severed thigh simply terminates in an indistinct red smear. It is hard to imagine how anyone could survive that much damage.

“I keep these pictures because it shows where I came from,” he explains. “It is a reminder that in life, even in the most difficult situations, it can get better.”

It is never easy to pull on a fake leg in the morning. Does he get angry and upset sometimes? Hell, yes. “But I don’t let it control my life,” he says. Ten years distant from the crime that sent him down a new road, Fucarile is happy, having found both love and purpose.

“What more can you ask for?”