Secrets & Lies | Chapter 2

Investigators assumed Sandra Birchmore took her own life. What did they miss?

Surveillance video from Sandra Birchmore's apartment building shows Matthew Farwell entering the building the last night she was seen alive. (Photoillustration by Maura Intemann)

Content warning: This story uses strong language and includes descriptions of violence, suicide, and the sexual abuse of children. (To read Chapter 1, click here.)

In early March 2021, after Sandra Birchmore’s body was autopsied by the state medical examiner, and then cremated, her family held a funeral Mass at Immaculate Conception Church in Stoughton. It was a small gathering, and somber.

Around that time, relatives also went to clean out Birchmore’s apartment in Canton, gathering up possessions she had unpacked just months before.

It had not been long since police officers had stood in the same rooms, surrounded by the same things, and seen clear signs Birchmore had killed herself. But as her family looked around, they saw testaments to a life Birchmore meant to go on living: the new stroller; a baby car seat, still in its box; the joyful sign she’d made to tell Matthew Farwell her news.

There was the half-done wash, one load in the washer, one in the dryer. Why would somebody who had decided to kill herself bother with laundry?

On February 1, the last day she was seen alive, she’d set about finding someone to care for her beloved cats while she gave birth, even though her due date was seven months away. Would Sandra really have suddenly left them to fend for themselves?

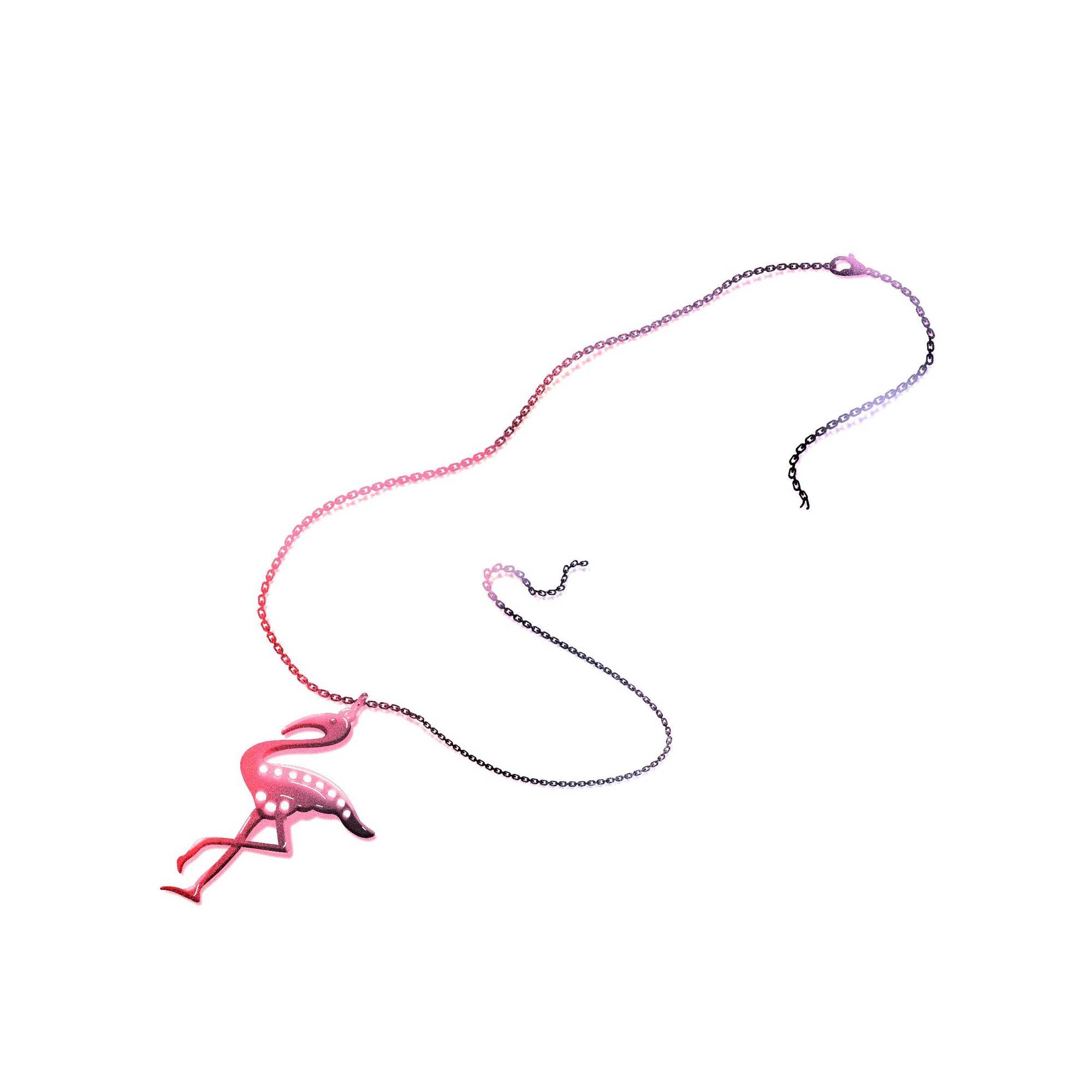

And then a relative found something on the floor of Birchmore’s bedroom, something that was never noted in police reports: Her precious pink flamingo necklace, the keepsake from her grandmother. A tangle of hair was caught in its chain. It was broken in the middle, not at the clasp. They later gave the necklace to police.

If investigators missed Sandra’s broken necklace, what else were they missing?

A lot, feared Birchmore’s friends and family.

From the beginning, everyone who knew Birchmore seemed convinced she would never do this, especially not like this. They found it impossible to believe that a woman who was constantly talking and texting about her life, who reached out every day for approval and affirmation and help, would end her own life without a word to anyone.

“This was a young woman who wouldn’t have a sandwich without posting it on three different social media platforms,” says her cousin Angelique Pirozzi. If Farwell had broken up with her, “she would have been on the phone to 15 different people. But no one heard from her again.”

Pirozzi, 53, is a union field organizer. Two days after Birchmore was found dead, she got to organizing. She posted on Birchmore’s Facebook page, urging people to contact the authorities with anything they knew.

Early on, at least 11 people left messages with authorities: a former college classmate, Birchmore’s hairdresser, and even the woman who had called the Stoughton police station to complain Birchmore owed her money. Many had information to share from Birchmore’s stories about Matthew Farwell, and the pregnancy about which she was so excited.

From the first days of the investigation, Pirozzi herself had been in direct contact with the state troopers assigned to the case. “My message from the gate was she was having a sexual relationship with a married police officer,” Pirozzi recalls. “She was excited about being a mom. No one thinks she killed herself, so you need to be looking at this very closely.”

For the longest time, it felt like those pleas came to nothing.

When police found Sandra Birchmore's body, her cellphone was nearby. (Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe)

When Canton officers found Birchmore’s body on the morning of February 4, 2021, they immediately called the office of the district attorney, which under Massachusetts law oversees all death investigations. The call was relayed to Trooper Matthew Dunne, one of the State Police detectives assigned to Norfolk District Attorney Michael W. Morrissey.

A preliminary theory had already taken hold. Canton officers were investigating an “apparent suicide death,” Dunne was told. He headed to Birchmore’s apartment.

Despite the initial appraisal, Dunne was keeping an open mind. “The cause and manner of death are pending further study,” he wrote in his report. That evening, Dunne’s supervisor, John Fanning, emailed Morrissey.

“There is more investigative work to be done on this case,” he wrote.

“I agree that this needs more help and work,” Morrissey replied.

In the ensuing weeks, records released to the Globe show, state troopers interviewed 20 people, half of whom had contacted Morrissey’s office themselves. The troopers followed up on some of their suggestions but none of it pointed them toward a murder charge.

In a 2022 statement, Morrissey’s spokesperson said the investigation “found no evidence of foul play” in Birchmore’s death. Eventually, his office gave up on a charge of statutory rape, which they had initially considered on the basis of texts they discovered between Birchmore and Farwell. That crime would be difficult to prove because the main witness, Birchmore, was dead, the 2022 statement said.

In late December of that year, state investigators began to focus on whether the texts showed Farwell could instead be charged with larceny — stealing from taxpayers, essentially — for meeting Birchmore for sex while he was on the clock, at Costco and Five Guys parking lots and elsewhere.

There is more investigative work to be done on this case.”—State Trooper John Fanning

A spokesperson for state Attorney General Andrea Campbell says that her office’s white-collar crime section has a case open, suggesting the larceny investigation is still being pursued.

How aggressively did state authorities investigate Birchmore’s death as a possible murder? It’s hard to say. Investigating agencies have withheld key records on the grounds that the matter is still open. And the leaders of those agencies — Morrissey; Dr. Mindy Hull, the chief medical examiner; and Colonel Geoffrey Noble, the head of the State Police — all declined to be interviewed for this story.

But a Globe analysis of the voluminous investigative record, obtained through dozens of public records requests, has revealed a number of missed clues — such as that broken necklace — along with red flags passed over, and investigative avenues not fully pursued.

None, on its own, was proof of murder, but together they form a body of evidence that experts say should have pushed authorities to fundamentally reconsider their suicide theory.

Should Farwell be convicted in federal court of killing Birchmore — he has pleaded not guilty — Morrissey will certainly face tough questions about how his office let him walk free for so long. And if Morrissey’s investigation failed Birchmore, a role may have been played by confirmation bias, the tendency to interpret new evidence as reinforcing an initial impression. Experts say investigations of apparent suicides are also often bedeviled by a kind of circular logic: She took her own life, so she was clearly struggling. She was struggling, so she clearly took her own life.

It’s apparent from records that state investigators heard and saw evidence that encouraged them to believe Birchmore was troubled, and troubled people are more likely to take their own lives.

But there’s another truth to consider in these cases: Sometimes, what look like symptoms of mental illness are also signs of abuse.

Advertisement

The first impression of suicide traveled fast, starting around 11 a.m. on February 4. Canton police officers told a detective that Birchmore had “hanged herself,” according to one report.

An officer made a call to Sheanna Isabel, a school resource officer in Stoughton, who’d known Birchmore for years. She told him the young woman had struggled after the deaths of her mother and grandmother. According to a Canton police report, Isabel also said Birchmore “had a history of claiming she was pregnant when she actually was not.” (Isabel says the context for her comment is redacted in the report, and she can’t elaborate.)

The officers would hear other stories about how Birchmore could exaggerate, or outright lie. This time, she was telling the truth. She had told friends she’d suffered at least one miscarriage, so she was considered high-risk. But her weekly blood tests suggested a healthy pregnancy.

Officers also met the building’s property manager, Erin Porter, to review security video from the lobby. The snippets from the day of the snowstorm show Birchmore picking up food, on the phone, and — the last time they saw her — coming in with the snowbrush, wearing the clothes they’d found her in that Thursday morning.

Soon, other police, including Dunne, were in Birchmore’s apartment, recording impressions for their reports. Dunne noted Birchmore’s messiness in some detail: clutter on every surface, a rug that looked like it hadn’t been vacuumed for a while, medications and trash on the counter.

Investigators who went to Birchmore's Canton apartment in February 2021 initially suspected she had killed herself. (Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

There was “no sign of a struggle,” according to Dunne’s report. No scuff marks or indentations on the wall, no drag marks on the floor. Birchmore’s body showed no defensive wounds. He noticed no bruising, swelling, or external trauma, nor any markings that would show she was trying to loosen the strap around her neck.

Trooper Kevin Tufts began to prepare a standard form for the medical examiner. Next to the field labeled “homicide,” he filled in “No.” Next to possible manner of death, he wrote “suicide.” And next to possible cause of death, “Intentional self-harm (suicide).”

Not everyone accepted the theory, however. That afternoon, an officer called Birchmore’s closest relative, her aunt Darlene Smith, to say Sandra had killed herself. Smith’s immediate reaction was disbelief. Suicide didn’t add up, she said. Her niece — her twin sister’s only child — was pregnant, and absolutely thrilled about it.

After police left that day, and the medical examiner’s staff took Birchmore’s body away, something clearly wasn’t sitting right with Porter. The property manager decided to study the security footage again.

This time, she spotted a man she didn’t recognize.

He entered the lobby — tall, wearing a COVID mask, his black hoodie pulled up over his baseball cap. He stepped into the elevator at 9:14 p.m. and came out 29 minutes later.

Porter alerted investigators. If not for her, they might not have seen Birchmore’s last visitor — a man they eventually determined was Matthew Farwell.

By the time police returned for another review of the video, Porter had passed on another tip.

A woman had called the complex’s emergency line, saying Birchmore told her that her police officer boyfriend wanted her to get an abortion — or “he would take care of the problem himself.”

A lot was happening on Friday, February 5, the day after Birchmore’s body was found. The state troopers were gathering evidence and conducting interviews. At the office of the chief medical examiner in Boston, pathologist Maria Del Mar Capo-Martinez was conducting an autopsy on Birchmore’s body. And in Stoughton, Police Chief Donna McNamara was entrusting her deputy chief with a sensitive task.

That morning in Sharon, Troopers Dunne and Tufts arrived at East Elementary School to interview Birchmore’s colleagues. According to Dunne’s report, principal Darrin Reynolds told them Birchmore’s aunt had mentioned a name to him on the phone: Matthew Farwell.

Dunne repeatedly asked the same question as he interviewed co-workers: Did Birchmore ever say she was afraid somebody would hurt her? Again and again, he heard no. “[I]f there were any safety or abuse issues in their relationship,” said a recess monitor who had become friends with her, “Birchmore would ‘definitely’ have shared that information.”

In Boston, meanwhile, it was up to Dr. Capo-Martinez to begin to determine the cause and manner of Birchmore’s death. Detectives routinely attend autopsies amid death investigations, but none from the Norfolk County DA came to the medical examiner’s office that day, according to visitor logs released to the Globe.

Dr. Capo-Martinez was still looking more closely at Birchmore’s case than is typical for a suspected suicide. The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner usually doesn’t perform autopsies in such cases — over the last decade, pathologists did them in only 1 in 4 of the nearly 6,000 deaths they deemed suicides, according to data from the state Department of Public Health. In deaths judged suicidal hangings, autopsies were performed in only about 1 in 7 cases.

In Stoughton, Chief McNamara ordered her second-in-command, Brian Holmes, to launch an internal affairs investigation. One of her detectives had apparently been having a sexual relationship with a woman, a former Explorer, who was pregnant and now dead. Holmes would be given wide latitude, and significant resources. McNamara also gave him as long as he needed to do it right. He would end up investigating for 19 months before releasing a report that would change everything.

Stoughton Police Chief Donna McNamara, shown at a 2022 press conference, entrusted her second-in-command to investigate the behavior of Matthew Farwell. (Jonathan Wiggs/Globe Staff)

By Saturday afternoon, Troopers Fanning and Dunne were ready to speak with Farwell. They’d heard he had been having sex with Birchmore and that her pregnancy was a problem for him. By then, they may also have suspected he was the man on the security video the last night she was seen alive.

They met Farwell around 3 p.m. in a Stoughton elementary school parking lot. The discussion was not recorded. It was also apparently collegial: Throughout Fanning’s 2½-page written summary, he refers to Farwell as “Matt.”

Farwell said he’d known Birchmore since her days as an Explorer. She’d “had a troubled life and he felt bad for her,” he explained, and he “would keep tabs on her over the years.”

Farwell admitted to having sex with Birchmore, but said it started in early 2020, when she would have been 22. He’d been drinking that first time, he told the troopers, and they’d only been together two or three times since. He couldn’t possibly have been the father of her child, Farwell noted — they hadn’t had sex since October 2020, and “the timeline didn’t add up.”

Investigators would eventually find evidence to suggest all those statements were false, as was his claim that he’d been trying to distance himself from Birchmore. In fact, he’d just asked for a key to her apartment, which troopers would soon learn from one of Birchmore’s cousins.

Farwell said Birchmore had been “sectioned” multiple times — involuntarily hospitalized for mental illness. That was an exaggeration, the FBI later determined. He also told the troopers that Birchmore “was having sex with other people during their entire time together.”

That she’d had multiple partners stuck with Fanning, who recorded that fact both in his report on the Farwell interview and, months later, in a memo to a supervisor about examining Birchmore’s laptop. “It appeared that Sandra had sexual relationships with other men in the months leading up to her death,” he wrote. “There were no threats of harm by any of these individuals, including Matt.”

As to the night he last saw her, Farwell told Dunne and Fanning he’d gone to her apartment to end the relationship — to tell Birchmore she was “crazy,” and the baby wasn’t his. They’d had “a pretty nasty argument” — she called him “a dick,” he said — but she was not despondent. He said she was standing in the kitchen when he left.

A married police officer’s admission that he’d been having sex with a woman he met when she was a child should have been “an immediate red flag,” says Tom Nolan, who was with the Boston Police Department for 27 years, and now teaches criminal justice at Suffolk University.

“There are limits to how much courtesy should be extended to a fellow officer. This guy is creeping around the scene at the time she died. Why aren’t we looking at him?” Nolan says. “And I mean a good hard look, not a conversation in the school parking lot that’s not recorded.”

Advertisement

The following week, Trooper Dunne was following up on leads, interviewing people who called the Norfolk district attorney’s office after Pirozzi’s post on Facebook. He asked them, as he’d asked Birchmore’s co-workers, whether they had seen any signs that she was being abused, or feared for her safety.

One friend volunteered to Dunne that Farwell was angry when, just after Christmas, Birchmore told him about her pregnancy–they’d fought so bitterly she’d kicked him out of her apartment. According to a State Police report, Birchmore told this friend Farwell said something like, “I wish you would kill yourself,” or “I wish you were dead.”

By this point, investigators were learning things that Fanning thought the medical examiner should know. On the morning of Tuesday, February 9, he emailed the pathologist’s office, hoping to speak to Dr. Capo-Martinez. Someone in the office suggested they talk Friday.

“Is there anyway we can do earlier in the week?” Fanning replied by email. “There are some issues that I’d like [the] doctor to know before then.”

This guy is creeping around the scene at the time she died. Why aren’t we looking at him?”—Tom Nolan, criminal justice professor

They made plans to talk, but authorities have declined to say what Fanning’s news was, citing the pending case.

A couple of hours later, Farwell came into the Norfolk district attorney’s office to turn over his personal phone at the troopers’ request, so they could download data from it. Farwell told them he’d deleted messages from Birchmore, but signed the consent form.

Later that day, Farwell apparently had second thoughts about cooperating. Using his department-issued phone, he made two Google searches, according to federal prosecutors.

First, he wrote, and then deleted, “can delete imessage be recovered hy cellebrite.” Cellebrite makes tools that help investigators study data from mobile devices.

Then, rethinking the form he’d just signed, Farwell made a second search: “can you revoke consent in Massachusetts.”

He deleted that question, too.

Chief McNamara outside federal court in Boston in August, after Matthew Farwell's indictment was announced. (Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

It’s common for friends and family to be in denial in the days after somebody takes their own life. But when the pushback continues, experts say, authorities should pay attention.

“Families saying ‘They would never suicide’ happens a lot, but I find that sort of feeling dissipates pretty quickly,” says Claire Ferguson, a forensic criminologist and associate professor at Queensland University of Technology in Australia, who studies homicides staged to look like suicides. “After the initial shock wears off, families start to see the signs a little clearer. When they don’t, it is very important that they are not ignored.”

Long after the initial shock wore off, the certainty that Sandra did not take her own life endured among those who knew her.

“I did not believe it for a second, because of the sole fact that she wanted a baby,” says her cousin Joshua Nee. “She always wanted better, she always wanted more out of life.”

She’d made it through far more trying times — to the wonder of those who knew her. “She didn’t want to die,” says Sue Rockwood, who taught Birchmore in high school English and later became a friend. “If she was going to commit suicide, she would have done it with all those obstacles and tragedies and family members dying, and just the struggle of everyday life. She persevered.”

Pirozzi, possessed of the same unshakeable conviction, would speak regularly to Fanning for months. He’d listen patiently as she proposed theories, she says. But, “There was always a plausible reason why it wasn’t what I thought it was.”

She wanted Fanning to get a DNA sample from Farwell, and have it tested to determine, once and far all, if he was the father of the baby Birchmore was carrying. The trooper seemed reluctant to do so. Farwell had already admitted to having sex with Birchmore, she recalls him saying, so what would a DNA link prove?

“I said, ‘It proves he’s a liar, and he could be lying about other things,’” Pirozzi says. “But it didn’t seem persuasive to him.”

Advertisement

As it happened, the answer to Farwell’s query about deleted messages was yes. Deleted iMessages, like Google searches, could indeed be recovered, though it would take some luck.

Pirozzi recalls Dunne saying they were having trouble unlocking Birchmore’s iPhone. She recommended the trooper try her laptop, explaining that the messages could also be found there. She was right.

Records suggest the State Police cracked the security on Birchmore’s MacBook fairly quickly. Her password was a variation of the name Matthew Farwell.

For a long time, Farwell had warned Birchmore to erase their most troubling exchanges, the FBI alleged much later in an affidavit. After one conversation, in which he said he wanted her to pretend he was raping her, he instructed her to “clear out this text.”

After he told her he wished he’d first had sex with her sooner, he texted “clear that part out baby.”

But there was something Farwell didn’t know, it seems: Although he and Birchmore had been scrubbing their phones, their messages had in fact been syncing automatically to Birchmore’s MacBook.

Investigators eventually recovered nearly 33,000 messages between them in the 14 months leading up to her death.

Their texts were in a massive data file, which one investigator described as “overwhelming” and “all over the map.” The conversations were so jumbled it was hard to tell who was talking to whom. Fanning and others spent weeks reviewing them all, looking for evidence of criminal conduct related to Birchmore’s death.

One thing they were able to make sense of was the conversations where the two talked about first having sex in April 2013, when Birchmore was 15.

On February 24, 2021, the Stoughton department placed Farwell on paid leave, pending the internal affairs investigation. Everything he’d wanted to avoid was happening. His secrets were coming out.

Matthew Farwell, shown in a 2017 post, joined the police department in his hometown of Stoughton in 2012. (Facebook)

A co-worker who met him at a bar around this time later told investigators that Farwell admitted having a sexual relationship with Birchmore. But he didn’t express any sadness about her death. Instead, he seemed annoyed that State Police were scrutinizing him.

Records show that troopers did in fact seek Farwell’s DNA shortly after Birchmore’s death. If they had obtained it, they could have compared it with samples from Birchmore’s clothing, her fetus, and the ligature around her neck, for example.

But by March 8, Farwell was done cooperating with police. He refused to provide a DNA sample, or submit to another interview with a polygraph test.

Those measures were “far outside the norm for a mere witness,” his attorney, Patrick Hanley, wrote to Fanning. “My client had no role in Ms. Birchmore’s death. He certainly never encouraged her to take her life, nor did he have any reason to fear she would take her own life.”

Troopers had other ways of getting a DNA sample, pursuing it surreptitiously or via a judge’s order. But it appears they dropped the effort.

“It is confusing, in light of all they knew, that they took his refusal to give a DNA sample at face value,” says Saul Kassin, distinguished professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “One can’t help but wonder how this would have played out if he was . . . not a cop.”

In some states, medical examiners send their own investigators to unattended deaths. They examine a body for signs of trauma, and search the scene for medication, notes, and other revelatory information. They also take their own photos, instead of relying on a State Police crime scene photographer, as happened in Birchmore’s case.

In deaths such as hers, evidence from the scene can be exceptionally important. It is often difficult to distinguish between self-hanging and strangulation via autopsy alone, experts say, because the same physical signs can be interpreted in different ways.

For example, the hyoid bone in Birchmore’s neck was broken. Some research suggests that’s less likely to happen in suicide by hanging — especially if a female victim is slight, as Birchmore was — and that the hyoid bone is more likely to break during strangulation. But it’s not conclusive.

“There are plenty of [research] papers out there that show overlaps between hanging and strangulation,” says Dr. James Gill, who heads the Connecticut medical examiner’s office. “You can’t always distinguish the two from an autopsy, so then it’s a question of looking more at the circumstances.” (Gill would only speak generally, not about the work of investigators in this case.)

Birchmore's cherished pink flamingo necklace was broken when investigators photographed her body. (Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe)

At the scene in Birchmore’s apartment, investigators appear to have missed a crucial piece of evidence: her flamingo necklace, found later on her bedroom floor by her family. In one photo taken by police that day, it was visible around her neck but already broken — the chain to the left, the charm to the right. It likely fell off her body when it was being prepared for transport by the medical examiner.

Although the necklace is in the photo, State Police never highlighted it in their reports. There was no note that it was broken.

“You wouldn’t expect a necklace to be broken in an intentional suicidal hanging,” Gill says.

Experts also note that women who hang themselves tend to first move their hair out of the way of the ligature. Birchmore hadn’t done that, according to a later review of photos by her family’s hired forensic expert, Dr. Michael Baden.

It was a long time before those pivotal photographs from Birchmore’s apartment made it to the Massachusetts medical examiner, internal emails show. Dr. Capo-Martinez did not request them until May 1, 2021, three months after Birchmore was found dead and just days before the pathologist would make her determination.

A spokesperson for the medical examiner’s office says a request for additional information that late in the process is not unusual. She declined to say whether Dr. Capo-Martinez had seen all of the photographs taken by State Police, and in particular the picture where the broken necklace was visible around Birchmore’s neck, referring questions about evidence to federal and state prosecutors.

Norfolk District Attorney Michael W. Morrissey in court. (Greg Derr/Pool)

By mid-May, emails show, Dr. Capo-Martinez had made up her mind, pending a review by the chief medical examiner. If the available evidence is murky in a case, the medical examiner has the ability to rule the cause of death “undetermined.” Dr. Capo-Martinez did not do that.

On May 21, 2021, Birchmore’s death certificate made it official. Cause of death: “Asphyxia by hanging.” Manner of death: “Suicide.”

If Morrissey’s office was ever seriously considering a murder charge, that suicide determination would be an obstacle to building a case. But the ruling was in line with how troopers saw the case as well. In a 2023 affidavit describing Birchmore’s death as a suicide, Fanning noted the medical examiner’s findings, as well as “physical evidence from the scene,” Birchmore’s mental health history, including “her past suicidal ideations which resulted in involuntary commitment to a health facility,” and “personal notes discovered.”

After the medical examiner’s ruling, Morrissey’s investigation into Birchmore’s death began to focus on the suspected larceny.

Pirozzi recalls Fanning assuring her they were still trying to hold Farwell accountable somehow. She was appalled. “It was just desperate,” she says now, “and not enough.”

But the district attorney’s investigation wouldn’t be the last word.

Advertisement

That spring, Stoughton Police Deputy Chief Brian Holmes had been building a team for his internal affairs investigation. He’d hire two private detectives and an IT expert — all retired state troopers — to help him conduct interviews and analyze phone data.

They would dig deep, but their scope was limited. Holmes’s job was not to investigate a possible crime, but to instead answer a question: Had Matthew Farwell violated the Police Department’s rules and regulations?

Before he was done, he’d find himself asking the same about William Farwell and Robert Devine.

On September 30, 2021, about eight months after Birchmore’s body was found, troopers provided Holmes with her texts — 50,000 pages of jumbled conversations. Holmes and his team set about examining them closely.

He was required to share any findings relevant to the State Police investigation, which took precedence, and so was in frequent touch with Fanning. Before too long, they got a better organized version of the messages, which made it easier to tell whom Birchmore was texting.

William had already told State Police he had sexual encounters with Birchmore, and that she’d told him she was pregnant with his brother’s baby. The internal affairs investigators eventually found William and Birchmore had been exchanging photos and videos “of a very sexually graphic nature,” while William was working, according to their report. William repeatedly “encouraged” her “to secretly record her sexual encounters with others” and then send them to him — a crime in Massachusetts. He also sent her images and videos of him having sex with a woman, “believed to be his spouse,” according to the state agency that stripped him of his police certification.

They also saw evidence in Facebook messages to suggest that Devine was seeking sex with Birchmore by 2020, according to the judge in the civil suit.

By the next spring, Holmes had assembled voluminous and potentially damaging evidence against the Farwells and Devine, and the men seemed to sense it.

Matthew Farwell remained on paid leave — he’d collected nearly $89,000 by then. But he was already beginning a new career, earning a commercial driver’s license and starting his own trucking business. He resigned from the Stoughton force April 1, 2022, right before Holmes was set to interview him.

A few days later, after a story in the Globe revealed the connection between Matthew Farwell and Birchmore, Devine and William Farwell were also placed on paid leave by the Stoughton department.

William Farwell resigned before Holmes could interview him. While he was on leave, he and his wife sold their house in Stoughton and moved to Maryland. On the day he was sworn in as a Transportation Security Administration agent in Baltimore, he quit the Stoughton police force. In his resignation letter, he denied “any/all allegations of misconduct,” and wrote, “I do not have confidence in the independence of the town’s investigation.”

The investigators spoke to Devine in mid-April of 2022. By that time, he’d graduated from law school and earned his license to practice law.

The interview appears to have been contentious. Asked when he first heard about Matthew Farwell having a sexual relationship with Birchmore, Devine snapped: “When he got put out on leave.”

He then corrected himself, admitting that Birchmore had in fact told him about it. He took care to note that she was describing sex between consenting adults. (He said she also told him about having sex with William Farwell, but that he didn’t believe her.)

Devine admitted to flirting with an Explorer in his program, though her name is redacted in the internal affairs report. But he said he didn’t know about the Farwell brothers impersonating police officers as teenagers, saying “that must have been before my time.”

That was “untruthful,” Holmes wrote in his report — it was documented that William Farwell said Devine counseled him after he pulled over the car.

Devine said he’d known Birchmore, and about her difficult home life, since she was a teen. She had an “obsession with police officers,” he said — she was always stopping by to chat when he was working, and offering to bring him coffee.

At some point in the interview, the investigators mentioned to Devine that they hadn’t found any direct communications between him and Birchmore. “Because you won’t find it,” he shot back.

But they did. On May 17, Holmes, his tech specialist, and Fanning analyzed Birchmore’s Facebook messages and connected Devine to “Marty Riggs.” He allegedly used the account to arrange meetings with Birchmore, one at the Chateau restaurant in Stoughton just weeks before she died. Marty Riggs–the person Hailee Sousa had once seen Birchmore messaging with constantly–is the name of the reckless but principled officer played by Mel Gibson in the Lethal Weapon movies.

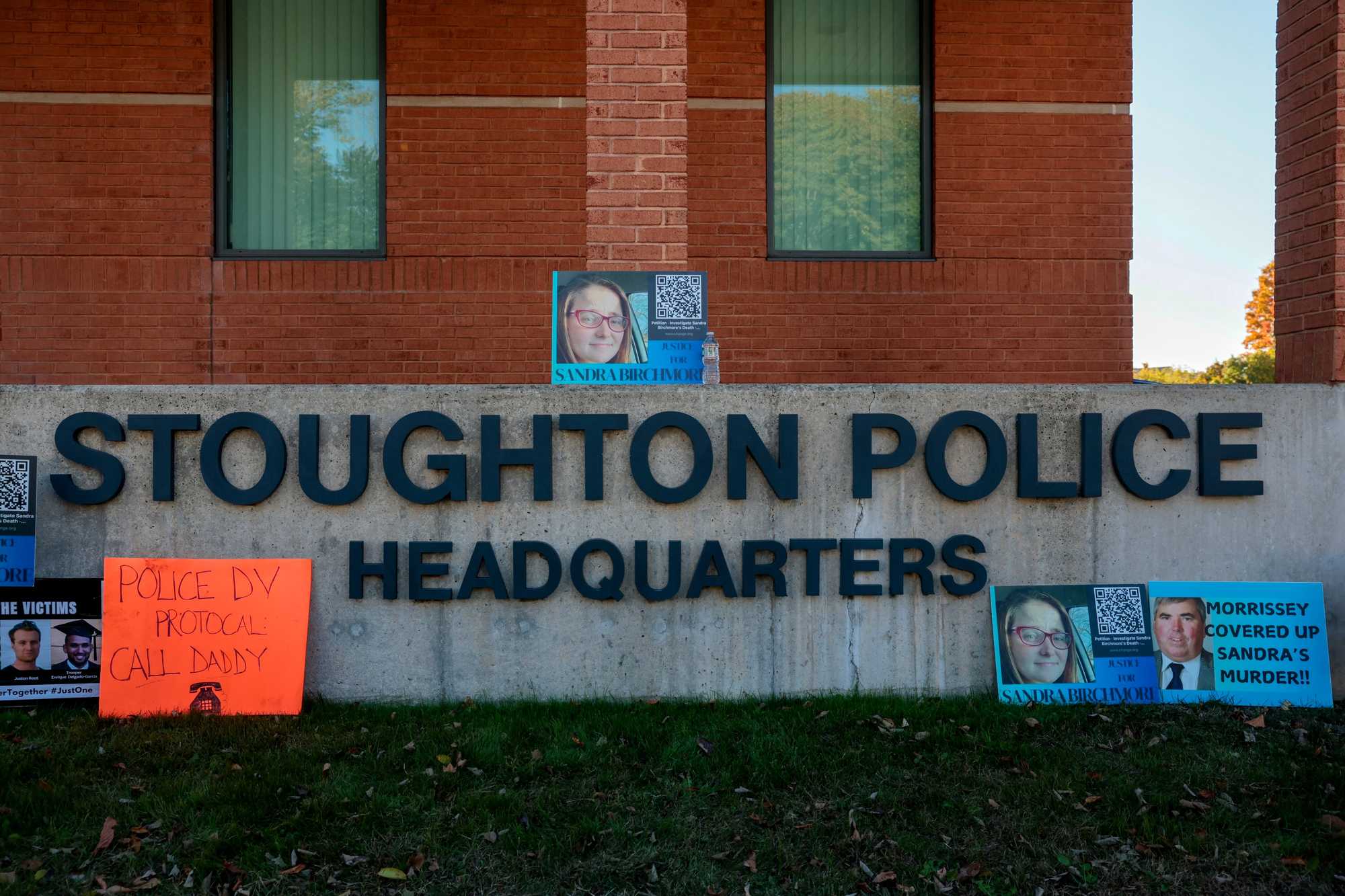

Community members held an event outside the Stoughton police station in October seeking "Justice for Sandra Birchmore." (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

“I do not view Robert Devine to be a credible person,” Holmes concluded in his final report. In Devine’s interactions with Birchmore, he detected echoes of the behavior that got him demoted from deputy chief years earlier.

Both inquiries found “exploitive, misogynistic and risk-seeking behavior that superseded his professional responsibilities,” Holmes wrote. ��“In both cases, Devine violated his inherent position of the public trust.”

Before a second interview could take place, Devine retired. “To be clear, I was completely truthful in my [internal affairs] interview,” he wrote in his resignation letter to Chief McNamara. “I had no personal relationship with Sandra whatsoever.”

He had a law practice now.

“I should caution you,” Devine continued, “should you try to defame me at the end of this, I am prepared to resort to every legal means at my disposal to fight you.”

A few weeks later, in September 2022, the allegations against the three officers came crashing into public view.

“All three men — the Farwell brothers and Devine — violated their oaths of office and should never have the privilege of serving any community as a police officer,” McNamara said at a press conference. She described Birchmore as a “vulnerable person” who idolized police and military members. She “was failed by, manipulated by, and used by people of authority that she admired and trusted right up until her final days.”

Those who loved Birchmore, most of whom knew only part of her story with the officers, were shocked by the extent of the exploitation McNamara described.

“She didn’t know what love was really, and she was just giving these guys whatever they wanted when they wanted, just to get some kind of attention, affection, whatever it is,” says Kellie Nee, Birchmore’s cousin. “They got their hands on her, they groomed her . . . and they’re like, ‘Oh, we can get away with this, because she’s got no family. She’s got no one to care for her.’”

Barbara Wright (at right), one of Birchmore's cousins, holds a sign near Stoughton Town Hall in October. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Birchmore’s estate — led by her aunt Darlene Smith — filed a lawsuit accusing the three former officers of wrongful death, assault and battery, and negligence, and accusing the Town of Stoughton of negligence for failing to supervise them adequately.

“This is a young woman who never had a chance,” said the family’s lawyer, Steven J. Marullo. All three men and the town have denied the allegations.

After the release of Holmes’s report, the Farwell brothers agreed to be decertified by the commission that credentials law enforcement officers in Massachusetts. Devine is fighting efforts to strip him of his certification.

It might have ended there, as yet another scandal in a police department that has reliably produced them for many years. But in late 2023, the US attorney’s office in Massachusetts began looking at the case. (The US attorney declined to comment for this story.)

FBI agents combed through the same evidence state troopers had collected. In the texts, they found messages displaying Matthew Farwell’s penchant for role-playing rape and incest fantasies, and for choking Birchmore during sex. In his iCloud account, they saw memes where the punch lines were about violence against women, choking, and necrophilia.

They also found reasons to interview people that other investigators hadn’t. Among them was the Stoughton police employee who took the call when Birchmore’s friend let slip that Farwell was having sex with Birchmore. That employee told agents that Farwell had become uncharacteristically angry and ordered his colleague not to speak of it to anyone — a pivotal moment, according to the FBI affidavit.

Morrissey’s office says it has no records about the Stoughton employee who took the call. (Stoughton police declined to comment.)

Federal prosecutors also said the texts showed that Farwell had lied repeatedly to investigators. He’d claimed he only had sex with Birchmore two or three times in the past year or so, but they found evidence suggesting it was at least 10 times. Regarding Farwell’s claim she’d been sectioned multiple times, they found only one instance — after the May 2020 blowup with her aunt — and she’d been evaluated at the hospital and deemed not at risk.

Even Farwell hadn’t thought she was in a bad place that day, the texts showed. “I wasn’t worried,” he’d written, immediately after she left the hospital, “I know you are fine.”

Birchmore’s longtime therapist had screened her for signs of depression and suicidality just days before she died and found none, the FBI noted.

The agents also detected a shift in Farwell’s tone in the weeks before Birchmore’s death, from controlling to something even more sinister, as Birchmore began demanding things from a man used to taking — that he get her pregnant, that he sign the birth certificate, that he support her child.

They saw, too, a motive for murder.

“You have threatened me from the word go if I didn’t do and give you what you wanted you would ruin me,” Farwell messaged Birchmore after she made her ultimatum. “I made a deal with you and you changed the terms at every turn.”

Three people told FBI agents that Birchmore said Farwell was so angry about the pregnancy that he had assaulted her. She told one friend that he had put her in a headlock, another that he had pushed her to the ground, and she confided in her therapist that he shoved her.

This past June, Dr. Michael Baden, the forensic pathologist hired by members of Birchmore’s family to review the state medical examiner’s determinations, made an explosive finding: This was a case of homicide, he said. Soon, another expert hired by the federal investigators, Dr. William Smock, came to the same conclusion.

In this image taken from video, Dr. Bill Smock, a Louisville physician in forensic medicine, testifies in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

Dr. Smock found that the fracture in Birchmore’s neck was inconsistent with the position in which she’d been found. In Dunne’s report from that day, he wrote he had seen no signs of trauma on her body. But Smock saw in photos an imprint on Birchmore’s chest from the strap buckle, though the buckle was up near her ear when she was found. The imprint “suggested blunt force trauma from an assault,” Dr. Smock determined.

And then there was that necklace she wore so often, broken at the chain, not the clasp. “The breaking of Birchmore’s necklace chain is consistent with a struggle,” Dr. Smock found, according to the FBI affidavit.

Perhaps the most ominous evidence came when the FBI looked at the health app on Birchmore’s iPhone, which tracks a user’s steps — an analysis that does not appear to have been done by State Police. The last movement it recorded was eight steps, around 9:40 p.m., a few minutes before Farwell was seen leaving on the security footage.

Farwell had said Birchmore was standing in her kitchen when he left. If that was true, she never again touched her phone, which was found on the floor of her bedroom days later, its battery long spent.

On the morning of August 16, 2024, federal investigators and Dr. Smock met with State Police, Dr. Capo-Martinez, and Dr. Hull, the chief medical examiner, to go over their findings.

The meeting — blocked out for three hours on Hull’s calendar — was a chance to compare their vastly different conclusions about Birchmore’s death: suicide from the State Police, the Norfolk district attorney, and the state medical examiner; homicide from Dr. Smock, the FBI, and the US attorney.

It was a chance, perhaps, for the state medical examiner to re-evaluate the cause and manner of death based on new evidence.

But nothing significant appears to have changed as a result of the meeting with federal prosecutors. The medical examiner stood fast.

Eleven days later, a federal grand jury indicted Matthew Farwell for allegedly strangling Birchmore and then staging it to look like suicide. He was charged with a single count of killing a witness, allegedly to prevent her from disclosing information on his possible federal crimes — civil rights violations and wire fraud among them.

Pirozzi was packing up her South Boston house, surrounded by boxes, when a federal agent called to tell her the news.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she says. “I still can’t believe it, that we actually might get justice.”

In response to questions from the Globe, a spokesperson for the medical examiner said that cause and manner of death are decided “based on the evidence available” at the time. She added, “We recognize that new information may arise as investigations progress,” and noted that any new evidence is reviewed by the medical examiner.

So far, the ruling of suicide remains in place.

On August 28, 2024, Matthew Farwell, now making a living in trucking, left his house before dawn, as he often did for work. But on this Wednesday, the last day of summer vacation in Easton, his elementary school-aged son climbed into the truck beside him.

Farwell’s arrest likely could not be delayed. A grand jury had handed down the indictment a day earlier, and word could travel fast. But the place they made the arrest was important, too: Usually, police try to do it away from a suspect’s home, especially if children might be there, or a suspect may have guns — there were 10 registered to his home address.

Around 10:45 a.m., Farwell pulled his gravel hauler into a parking lot near the McDonald’s at the Northgate Shopping Center in Revere. As he got out of the truck, agents — some in tactical gear — swarmed him. Guns drawn, they took the former police detective down to the pavement.

Shaky cellphone footage from a bystander shows Farwell, in ripped jeans, a black T-shirt, and work boots lying face down, surrounded by officers, his hands behind his back. He surrendered quietly.

On a curb nearby, two women, both agents, tried to comfort the boy. He sat with his head in his hands as his father was taken away.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Laura Crimaldi and Yvonne Abraham

- Editors: Francis Storrs and Gordon Russell

- Project managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Craig Walker, Suzanne Kreiter, Pat Greenhouse

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Video producer: Randy Vazquez

- Design: Ryan Huddle and Maura Intemann

- Illustrations: Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe

- Development and graphics: Kirkland An

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Carrie Simonelli

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Research assistance: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC