Secrets & Lies | Chapter 1

Sandra Birchmore put her trust in the police. They broke it.

Sandra Birchmore was 23 years old when she was found dead in her Canton apartment in 2021. Initially, investigators suspected suicide. (Family photo, photoillustration by Maura Intemann)

Content warning: This story uses strong language and includes descriptions of violence, suicide, and the sexual abuse of children.

It was deep into a long pandemic winter, but Sandra Birchmore was happy. She’d long dreamed of being a mother, and now she was pregnant.

On Monday, February 1, 2021, a nor’easter was sweeping into Massachusetts, threatening to drop a foot of snow. The school where the 23-year-old worked had let out early, around 12:30 p.m., and now she was busy at her Canton apartment, cozy in teal leggings and a fleece, her long hair pulled into a high bun. Around her neck, she wore a pink flamingo charm on a thin gold chain, a keepsake from her late grandmother.

With her afternoon free, Birchmore was planning for the future. She decided to send out a pregnancy announcement on Valentine’s Day. She contacted a newborn photographer, and arranged for somebody to care for her cats when she was in labor, though her due date was seven months away. She was impatient to give her own baby the carefree childhood she’d never had.

Birchmore needed this. Her adolescence had been difficult, with the money troubles and stress that came with her single mother’s constant health challenges. But the last few years had been exponentially harder. When her mother died in 2016 — followed by the grandmother she adored just weeks later — Birchmore felt lost. With no immediate family left, her “support network had essentially broken down,” a cousin recalls.

She’d had big plans, but none had panned out. She washed out of the Army Reserves, and was let go from her job as a mall security guard. She looked up to police — she’d been in Stoughton Police Explorers, a junior academy for teens — but her lifelong goal of becoming an officer seemed to be slipping away, too. And really, some who knew her wondered, what kind of cop would she have been? She was just 4 feet 10 inches tall, and when someone got in her face, she seemed to shrink even smaller.

But here Birchmore was, 10 weeks or so along in her pregnancy, and it felt like she was finally turning the corner. She’d been taking courses for nursing school, had a new job, and was settling into her first apartment. She was already talking about upgrading to a bigger unit when the baby came.

Birchmore’s colleagues at the elementary school, where she’d recently been hired as a teacher’s aide, called her an “oversharer.” But she didn’t tell everybody everything.

She’d told only a few people that the baby’s father was Matthew Farwell, a 35-year-old police detective in Stoughton who looked the part — 6 feet 4 inches, 225 pounds, cop haircut. His wife was due to deliver their third child the next day, February 2.

In 2014, Sandra Birchmore (far right) and her fellow Stoughton Police Explorers. (Stoughton PD Facebook)

Birchmore told still fewer people that she and Farwell had been having sex since she was 15 — under the age of consent — when he was one of her mentors in Explorers. She knew Farwell would be ruined if that got out. For a decade, he’d had all of the power in their relationship. Now Birchmore felt like she had some too.

Farwell didn’t like that. When she told him she was expecting, just after Christmas, he was angry. Though he’d agreed to have unprotected sex, he accused her of blackmailing him into it. Birchmore said Farwell had become violent, putting her in a headlock and grabbing her phone out of her hand. Then, a friend called the Police Department and said the two were having an affair, which further enraged Farwell. He demanded to know who else she’d told.

“Take your baby and run,” another confidante had warned her.

But Birchmore didn’t take her baby and run. And now, suddenly, Farwell had seemed different: calmer, kinder, more open to the commitment she was asking for. He’d even requested a key to her apartment, something he’d previously resisted.

So, when Farwell unexpectedly texted on the night of the snowstorm, to see if he could “come by for a second,” Birchmore would have been pleased. He already had the code to get into her building. She told him she’d leave her apartment door unlocked.

The security camera in the lobby recorded him walking in four minutes later, wearing a baseball cap, his hood pulled up over it. Covering his face, he wore one of the COVID masks he was known to despise.

Advertisement

She had been gone for days by the time they found her.

Her colleagues at East Elementary School in Sharon were worried because she hadn’t shown up for work. Nobody had been able to reach her since that Monday night, and now it was Thursday morning. They called the police.

There was no answer at her apartment, so two Canton police officers got a key from the property manager to let themselves in. The place seemed empty, apart from the two cats padding around. Then they opened her bedroom door.

It looked like a suicide.

Birchmore was seated on the floor, up against her closet. Her skin was blue. A strap was attached to the handle of her closet door, and pulled tightly around her neck — so tightly that a forensic pathologist later said she would have lost consciousness in under 10 seconds, and died within minutes.

On the floor, 12 inches from her right hand, lay her cellphone. It had locked at 9:13 p.m. on Monday, investigators later determined, and stayed that way. Her phone was like a part of her — ”her third hand,” as a friend described it. She was on it constantly, talking and texting, narrating her days.

Birchmore’s whole life passed across that little screen. And the whole story of her death, if only someone looked closely enough.

Her loved ones would spend years trying to make someone look closely enough.

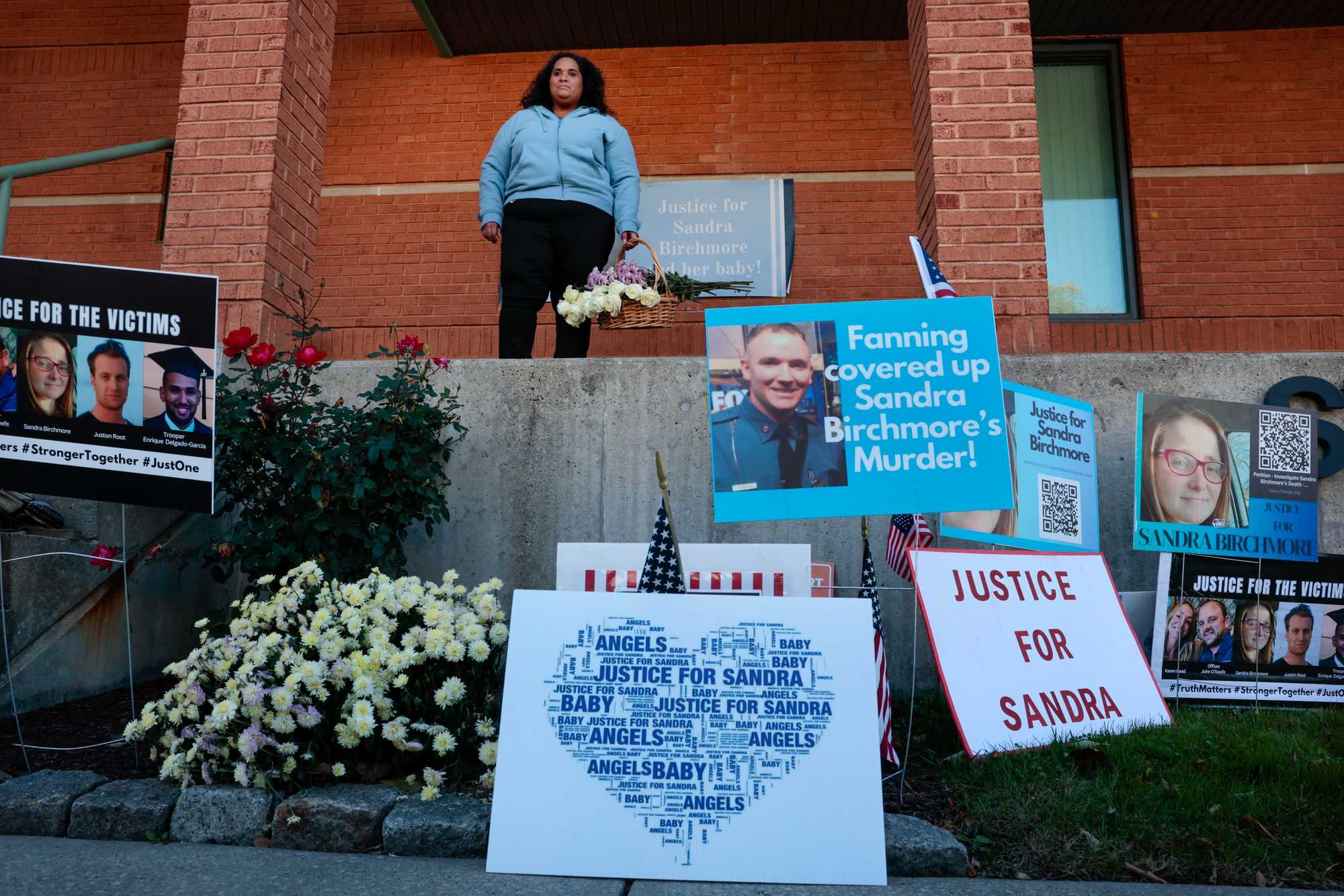

Community members gathered outside Stoughton police headquarters in October demanding "Justice for Sandra Birchmore." (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

As the news of Birchmore’s death spread from relative to relative and friend to friend, they connected the pieces of the stories she’d shared, and one overriding suspicion quickly took root: No matter how it looked, Sandra didn’t take her own life — Matthew Farwell took it from her.

“Sandra’s pregnancy was a ticking time bomb for this guy,” says Birchmore’s cousin Angelique Pirozzi. “His personal life was about to implode.”

Questions about Birchmore’s death — and what had been happening to her in the days and years leading up to it — would spawn three separate but intertwined investigations.

The first was an inquiry into her death, conducted by the state medical examiner and State Police detectives assigned to the office of Norfolk District Attorney Michael W. Morrissey. After four months or so, that investigation concluded Birchmore’s apparent suicide was an actual suicide, infuriating those who loved her. To some, it seemed as if the detectives accepted everything at face value.

The second was a Stoughton police internal affairs examination of Matthew Farwell’s interactions with Birchmore. That one would eventually bring a cascade of ugly and shocking revelations into the open, not just about Farwell, but also two other Stoughton officers — his twin brother, William, and their mentor, former deputy chief Robert Devine. The blistering report would expose what they and others had allegedly been doing to Birchmore for years, and prompt a civil suit from her family.

They “passed her around like a toy,” is how an attorney for Birchmore’s family put it in a court hearing.

The third investigation didn’t begin until almost three years after Birchmore’s death, when agents at the FBI’s Boston office took the unusual step of opening their own inquiry. They used much of the same evidence the previous two teams had unearthed, but also found key details that had been missed.

From left/top: Matthew Farwell, Robert Devine, and William Farwell, all formerly of the Stoughton Police Department. (Stoughton Police Department, Associated Press)

This past summer, federal prosecutors announced they had enough evidence to support what Birchmore’s loved ones had been saying from the beginning. They charged Matthew Farwell, now 39, with strangling Birchmore to protect his secrets and staging the scene to make it look like she’d taken her own life. The federal charge carries a potential sentence of death.

“He allegedly attempted to cover his tracks to literally try and get away with murder,” Joshua Levy, then acting US attorney, said at a press conference in Boston on August 28. “And he almost did — until today.”

Farwell has pleaded not guilty and is in a Rhode Island detention facility awaiting trial. His public defenders say rules of conduct “expressly forbid” them from commenting on the allegations, or the evidence in his case, and from disputing assertions in this story. “We ask your readers to reserve judgment until they have all the facts,” they wrote in an email.

William Farwell admitted he also had sex with Birchmore when she was an adult. As for Devine, the internal affairs report included Facebook messages from 2020 in which he “asks her for sex acts and discusses rendezvous locations,” according to a judge in the civil case. Devine denies this. Neither man has been charged with a crime, but the Birchmore family’s suit seeks to hold them and Matthew Farwell accountable for her death. William Farwell, Devine, and their lawyers did not respond to requests for comment. All three men have denied wrongdoing.

The brothers resigned from the Stoughton police and agreed to be stripped of their ability to work in law enforcement by an oversight commission; Devine, 52, chose to retire and is fighting efforts to take his certification away.

But all of that was years away from that cold February day in Canton in 2021.

To understand why and how it took so long for investigators to get from there to here, the Globe obtained thousands of pages of court filings, police reports, and internal investigative records. Since April 2022 — when the Globe first exposed Birchmore’s pregnancy and her 10-year alleged relationship with Matthew Farwell — Globe reporters have interviewed dozens of people who knew Birchmore, or dealt with the aftermath of her death.

Acting US Attorney Joshua S. Levy, at right with Stephen J. Kelleher of the Boston FBI office, revealed in August that Matthew Farwell had been indicted. (Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

The investigations, charges, and recollections tell a story that is, in some ways, sickeningly familiar: An alleged predator chose his victim well, before she had the capacity to know what was happening to her, and leveraged her vulnerabilities against her — for a decade. The damage done to Birchmore left her open to exploitation by others, too.

But there is more here.

The immense power imbalance that Birchmore endured in her life persisted long after she was gone. Time and again, investigators gave the benefit of the doubt to the police officer now accused of killing a young woman who was rarely, if ever, granted the same consideration.

That is how the story of Sandra Birchmore’s life and death might have remained, if not for the cellphone — the vessel into which she poured all of her dreams and dramas — lying on the floor beside her body.

The Stoughton police had been part of Birchmore’s life — and a vital part of her family’s support system — since she was little. She and her ailing mother, Denise, had it tough at times, and police were there at some of their most difficult moments. Birchmore idolized them.

And, like so many other children victimized by authority figures their struggling parents trusted, the girl’s vulnerabilities left her susceptible to abuse.

Denise was a widow at 31. Her husband, Warren Birchmore, died in 1995 after being hit by a truck in a Boston crosswalk. A year and a half later, Sandra was born. The name of her biological father isn’t on her birth certificate — that had always bothered Sandra, friends say — and he was not part of her life.

“I think it was hard for her, not having a father,” says Earl Carter, a family friend.

Denise had constant health problems that kept her out of work, so money was tight. “I don’t remember a day when she wasn’t sick with something,” says Barbara Wright, a cousin.

Relatives recall Sandra, an only child, tending to her mother from a very young age, keeping Denise on track with her medications. To some, it seemed like Sandra was the mom, rather than the other way around. “She was never brought up like a child,” says Kellie Nee, who married into the family. “She was a young adult at an early age.”

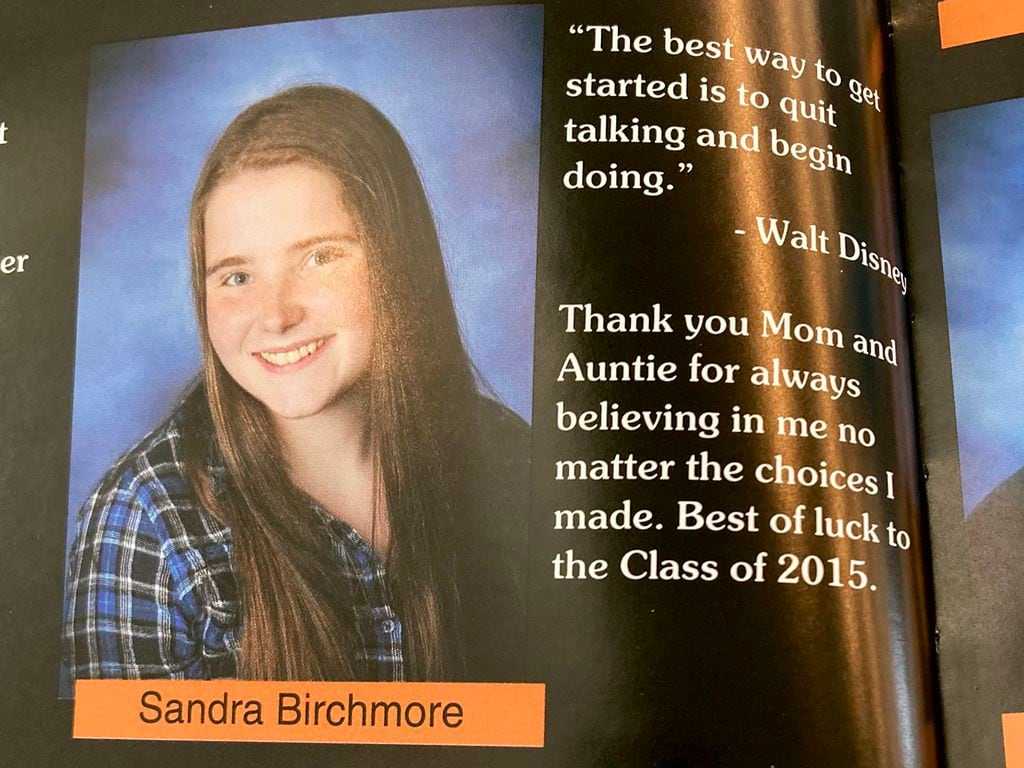

Birchmore's senior portrait in the Stoughton High School yearbook. (Laura Crimaldi/Globe Staff)

The Birchmores lived in a Stoughton apartment, but a split-level house nearby on Holbrook Avenue felt most like home. It was owned by Denise’s aunt and uncle, Claire and Gerald Gaudet, who’d raised Denise and her siblings as their own.

The Gaudets also lavished love and attention on Sandra, who thought of them as grandparents. They rented a bouncy house for her First Communion, hosted her friends at their aboveground pool, and surrounded her with a big, sprawling family that converged on their home every Christmas.

“Her grandmother was her best friend,” recalls William Kilroy, who dated Sandra Birchmore when they were students at Massasoit Community College.

Sandra was fiercely protective — as a kid, she insisted to a friend they get off their bikes and walk them through crosswalks — and unfailingly loyal. That continued through her adulthood, where she could be exhausting to be around, but was also generous: happy to drive for hours to pick up a stranded friend, or check in on a sick relative, or to comfort somebody after the loss of a beloved pet.

As she was growing up, she was also “a handful for her mother,” Nee says.

Wright, her cousin, recalls a family gathering when Sandra was 6 or 7. “She almost ran into me, and I said, ‘Hi, Sandy.’ And she looked at me, and she stamped her feet. She said, ‘Don’t call me Sandy. My name is Sandra!’ " Wright says. “That was my first introduction to her feistiness.”

In 2006, when Sandra was 9, she and Denise participated in the town’s Strengthening Families Program, designed for “high-risk” children and their parents. Each week for 14 weeks, families met at a Stoughton church to learn communication and coping skills.

Denise seemed to most appreciate the tips on keeping the peace at home. “I liked the fact that they showed you what your tools are,” she told a local reporter. “For example, instead of yelling at your child, sit down and talk it out.”

The workshop was sponsored by OASIS — a Stoughton consortium of juvenile court officials, schools, police, and others — which counted Robert Devine among its cofounders. He was also director of community policing for the force, a job that involved forging personal connections among officers and the people they serve and protect.

At the time, leaders sorely needed to rebuild trust in a department tarnished by an extortion scandal and other controversies. “We’re not here to hurt [residents], flex muscles, or overuse authority,” Devine promised at a department open house, which drew some 200 neighbors.

In 2010, Devine ran an announcement for his Explorers program in the Stoughton Journal. “OASIS and the Police Department believe in your kids and wishes to give them a positive foundation from which to build future success,” it read, touting how graduates went on to military academies, Ivy League colleges, and successful careers.

To Denise, Explorers sounded like a place where Sandra “would be surrounded by role models within this field that she was interested in,” Pirozzi recalls.

Sandra signed up that year, when she was 12.

Advertisement

A decade earlier, when Matthew and William Farwell were recruits in Devine’s first class of Explorers, the twins sorely needed structure.

They’d been having a hard time in Stoughton schools. Whenever Matthew’s middle school classmate Devin Howell got sent to the principal’s office, it seemed like Matthew was already there. “He had, like, his own desk,” Howell says. “It was bad.”

William, who went by Billy, cycled through four high schools.

When Devine was ordered to take over the Explorers program — originally an offshoot of the Boy Scouts — the Coast Guard veteran turned it into a paramilitary operation, with uniforms, calisthenics, and drill instructors.

He could be tough, exhorting Explorers to do push-ups and sending them on runs across town. “We had to say ‘Yes, sir!’ We had to really be obedient,” recalls A.J. MacQuarrie, an Explorer from that time. But Devine also had a gentler side. “He had this paternal energy and, like, this safe energy.”

Over time, Devine’s personnel file would swell with testimonials from grateful parents and students. “I just want to say thanks to Sergeant Devine for believing in me when I tried to quit,” wrote one Explorers graduate, who hoped to become a police officer after college.

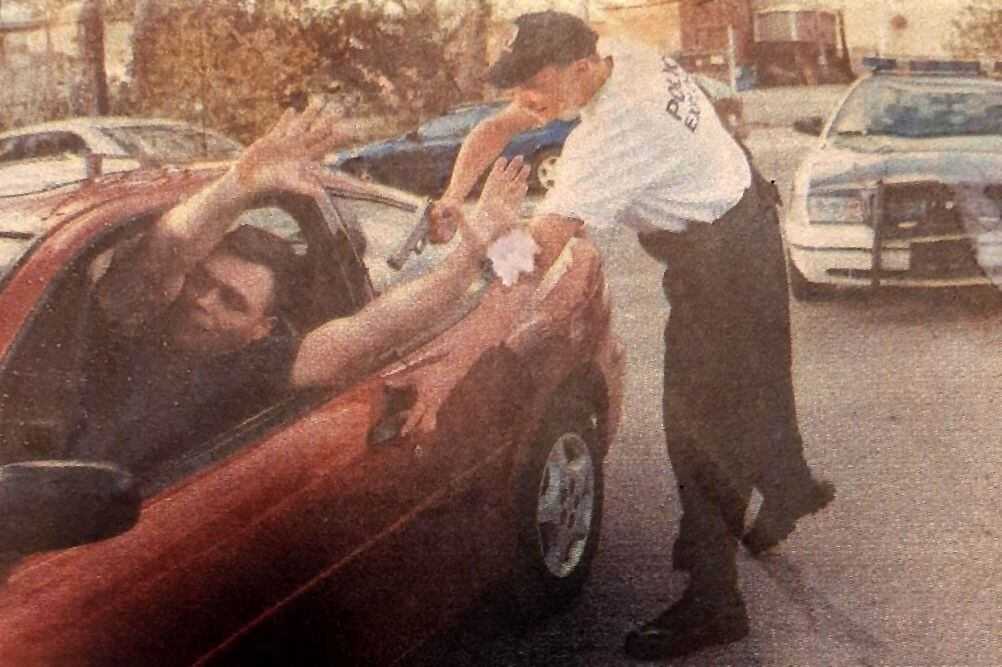

The Farwells had also long wanted to be police officers, and they took to Devine’s lessons with enthusiasm. A 2002 photo for a newspaper story about the program shows Devine, playing a driver, leaning out a car window with his arms raised. Matthew, then 16, stands behind him, playing the role of the officer — and pointing a replica gun at Devine’s head.

At age 16, in 2002, Matthew Farwell posed for a photo holding a replica weapon while demonstrating a traffic stop with Robert Devine. (Jim Walker / USA TODAY NETWORK)

The exercise was intended to teach Explorers how to safely conduct a traffic stop. “My favorite part is when we practice what we’ve learned,” Matthew told the newspaper.

The brothers apparently did just that: While still a teenager, William was accused of pretending to be a police officer and pulling over a real driver.

He’d bought a white Crown Victoria, the kind popular with police departments, complete with a flashing light. As the brothers were tooling around town one day, another driver cut them off. William turned the light on — it was “a scare tactic,” he later said. He insisted he never got out of his car.

Stoughton officer Shawn Faria, however, remembered it differently, as detailed in police records. Seeing William outside the car and thinking he was a cop in plain clothes, Faria pulled up. “Are you all set?” he asked. That’s when he realized William wasn’t an officer, but “a kid from the Explorer program.”

Impersonating a police officer is a serious offense, but little seems to have come of it at the time. William later said he was “counseled” by another officer and by Devine, his Explorer mentor.

If Devine took care of the brothers, that wasn’t surprising to those who knew them. Ashley Bell, an Explorer during those years, says they “were under his wing.”

Decades later, a Stoughton police internal affairs report would put it more bluntly: The brothers were Devine’s “understudies.”

Both brothers dropped out of high school before graduation, though Devine invited them back to Explorers as volunteer instructors, and they eventually earned their GEDs. And both eventually became Stoughton police officers — though each needed the benefit of a second chance at applying, and a decisive assist from Devine.

“They grew up right before my eyes,” Devine told a reporter in 2012, just after Matthew was hired. “If we played even a small part in their success, I’m proud of that.”

By 2010, when Birchmore was accepted into Explorers, her struggles were well-known around town. Her mother’s health was failing, and kids in middle school mocked the odor of cigarettes wafting off her clothes. One night in June, she and Denise had to go to the police station — girls from school had called their home three times, threatening to beat up Sandra.

“There was nothing easy for her,” says Christine Wahl, one of Sandra’s school friends.

Sandra took medication for ADHD and asthma, and sometimes visited the school nurse three times in a single day. A guidance counselor was teaching her strategies for making and keeping friends, and there were frequent calls home to Denise.

“She needed some extra support; mom needed support, too,” recalls Matt Colantonio, who was then an assistant principal at Sandra Birchmore’s middle school. “They were that family you work with a little bit to get them through.”

But in Explorers, Birchmore found a place to belong. She wore her black uniform T-shirt with pride and excitedly told friends about running laps and racing other recruits, as fast as her asthma allowed.

“She loved it,” says a friend from childhood. “She was really working on herself, you know? And there was camaraderie — she was making friends.”

(Some of the people who knew Birchmore requested anonymity for this story, either because they said they fear police retaliation or professional repercussions for discussing her publicly.)

There was nothing easy for her.”—Christine Wahl, one of Sandra’s school friends

When Birchmore was starting in Explorers, Matthew Farwell had just become a police officer in Wellesley. With Devine’s encouragement, he’d enlisted in the Army, serving nearly four years — including six months in Afghanistan — and rising to sergeant. Farwell then applied for the Wellesley job, and Devine gave him a glowing recommendation. “My own opinion of Matt could not be any higher,” he wrote, citing Farwell’s “strong moral character,” “courage to do the right thing when most people might not,” and his “uncanny way” of putting people at ease.

Still, Farwell was eager to transfer to his hometown department. Stoughton Police Chief Paul Shastany passed him over the first time, after Farwell canceled his interview at the last minute. Farwell tried again and made it in 2012.

William Farwell was applying to Stoughton as well — the brothers were inseparable — but Shastany also rejected his first application, in 2011. His record — including being discharged from the Army for going AWOL for several months — was behavior “inherently incompatible with police work,” Shastany wrote. But William eventually distinguished himself as an explosives-disposal expert with the National Guard, including in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing. He was finally offered a job on the Stoughton force, too, which he accepted in 2017.

Shastany says he was persuaded to reconsider both brothers because of their military and other experience — and because Devine promised him they’d matured. “I was assured by Devine that those childhood pranks were cured when they went into the military,” Shastany says. “So I was willing to concede that, ‘OK, nobody is perfect.’”

Once Matthew Farwell became a Stoughton officer, it didn’t take long for him to become a regular presence in Birchmore’s life. He began meeting her at the town library, ostensibly to help her study. On October 28, 2012, he sent the 15-year-old a friend request on Facebook.

Farwell was building trust he would later exploit, federal prosecutors allege. Experts say this is how grooming works: A trusted authority figure takes an interest in one of his charges, stepping in to fill a void — an absent or overwhelmed parent, for example — and to outside observers, that looks healthy, even lucky.

At least one relative knew Birchmore was meeting with Farwell, but heard he was helping with her homework. “It can be really difficult to tell what’s going on” in grooming situations, says Judith Zatkin, an assistant professor at Bemidji State University in Minnesota who studies sex abuse in organizations that serve youth. “It can often seem like an adult helping out a kid who just needs a little bit of extra support.”

After Matthew Farwell joined the Stoughton department in 2012, he became involved in Birchmore's life, including meeting her at the local library. (Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe)

For six months, Farwell escalated his attentions. In April 2013, his interactions with Birchmore crossed into criminality, according to federal prosecutors: He had intercourse with her for the first time. Farwell has denied this.

Such an encounter would qualify as aggravated statutory rape under state law. She was 15; he was 27. The next month, Farwell married his fiancée.

Years later, Farwell and Birchmore looked back on that day in a series of explicit text exchanges, spelled out in an FBI affidavit. (In this story, the Globe is quoting electronic communications as they appear in documents.)

Elsewhere in the texts, Farwell said he’d wished “it had been a year sooner after helping you study at the library.”

Birchmore replied she’d wanted that as well, but was too scared to say anything, thinking he’d balk — ”cause of my age I didn’t want you to be like uhhh no wtf.”

Explorers pulled Birchmore into Matthew Farwell’s orbit, and provided cover for his allegedly predatory behavior, according to investigators.

The program gave plenty of kids discipline and direction, as intended, but in doing so brought adults and impressionable teens into close and frequent proximity. With little oversight, there came opportunities for the mentors to blur the lines with their young charges — unless the person running the operation was militant about boundaries.

Robert Devine was not that person, according to the 2022 internal affairs report by Stoughton police.

That report describes portents of trouble in the program dating to the early days of Devine’s leadership, including lax oversight and a tolerance for flirting. Those aren’t crimes, but the report paints a portrait of ethical lines stepped up to — and, in time, stepped over.

Ashley Bell, now a mom with her own 12-year-old daughter, belonged to the Stoughton Explorers at the same time as the Farwell brothers. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Ashley Bell was 12 when she enrolled in Explorers and an after-school program also overseen by Devine: open gyms at her middle school, where kids could gather to play basketball and hang out. Bell developed a crush on the charismatic officer — she thought he looked like Jon Bon Jovi — writing his initials on her hand with a gel pen and giving him cards and chocolates.

She believes Devine carried himself in a way that encouraged such attention. “He definitely seemed to be showing off,” she told investigators many years later, and “basking in kids admiring him.”

Bell was heartbroken in 2002 when she learned Devine, then in his early 30s, was engaged. When he saw her crying, he led her to a storage closet off the gym, out of view of the others. He lifted her up, and sat her down on a desk.

“You’re a knockout,” Bell recalls Devine saying. “When you’re 18, we’re gonna go out together. I’m gonna take you on a date.”

He kissed her forehead, gave her a long hug, and helped her down.

Bell left, followed outside by the Farwell brothers, who were in high school then but often hung around the middle school gym. They’d be given leadership roles with Explorers that year — Matthew as “deputy chief,” William as “lieutenant.” As Bell sobbed over Devine, Matthew, too, gave her a long hug.

Bell remembers feeling like Devine wasn’t really closing the door to her adolescent affections.

A teenage Ashley Bell left a love letter for Robert Devine at the police station. (Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe)

Jenn DeAngelis overheard her daughter talking to a friend about the note and immediately drove to the police station. She stormed into Devine’s office, saying, “Where’s the fucking letter?”

Devine said he had no idea what she was talking about, DeAngelis recalls. But she spotted a crumpled paper in his trash can and they both lunged for it. DeAngelis got it first and recognized Ashley’s handwriting.

“Let me tell you something,” she said. “You go near my kid again, I’m going to shoot you with your own gun.”

Bell, now 35, with her own 12-year-old daughter, makes clear that nothing sexual ever happened with Devine. She cringes at her younger self, but remains angry that Devine let her carry on her fantasy, rather than telling her it was inappropriate.

“A wrench was thrown into my coming of age — it was totally hijacked by Rob Devine,” she says. “My whole entire middle school life revolved around him because there was no oversight, there were no adults to say, ‘This is wrong.’”

At least once, an authority figure did notice something, and felt the need to speak to Devine about it. He had been seen visiting with a “scantily clad” female student, possibly an Explorer, in his office, according to the internal affairs report. The person who saw it — the name is redacted — ”confronted Devine about the optics of the visit and cautioned Devine about being smarter.”

Jenn DeAngelis (left) says she confronted Devine at the police station in 2002, after learning that her daughter, Ashley (right), had written him a love letter. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Despite the scolding, Devine continued to lead Explorers, until a major scandal became public. A 2015 Stoughton Police internal affairs investigation determined Devine — deputy chief at the time — had improperly used his power to address a personal matter.

In the fall of 2014, Devine was trying to end an affair with a local woman, whom he said he began seeing when he and his wife were separated. He claimed the woman became suicidal and threatening — he worried she would “expose the relationship to embarrass him and humiliate his family,” he later told investigators — and got a court order prohibiting her from contacting him.

Soon after, Devine began receiving anonymous harassing messages, and he directed a subordinate in the department to examine his phone. State Police and the Norfolk DA’s office investigated and arrested the woman on charges of violating the order. (The Globe is not naming the woman because the charges were dropped.)

During that investigation, Devine continued seeing the woman, police later learned. The internal probe concluded he had been “untruthful by omission,” improperly used his power to address a personal matter, and demonstrated “a distorted understanding of right and wrong.”

Shastany wanted Devine fired, but Stoughton officials feared civil service laws would protect him — perhaps even keep him in police leadership. The punishment the town ultimately decided on led Shastany to resign in disgust. Devine was demoted from deputy chief to patrolman, the department’s lowest sworn rank. After serving a 60-day, unpaid suspension, he was back at work.

But that was later, in 2016. For much of Birchmore’s time in Explorers, Deputy Chief Devine had a sterling reputation.

Advertisement

As Birchmore made her way through high school, her commitment to Explorers — and to Matthew Farwell — deepened. After their first encounter in April 2013, prosecutors allege, Farwell and Birchmore began to meet with some regularity for sex in his police car or truck.

In Explorers, she was always the first to show up, and among the last to leave. In June 2013, she was promoted to a leadership role. The photo she posted on Facebook showed her smiling proudly, arm-in-arm with Devine and Shastany. She captioned it: “Achieved sergeant :)”

A photo Birchmore posted on Facebook in 2013 shows her with Robert Devine (left) and former Stoughton Police Chief Paul Shastany. She captioned it "Achieved sergeant : )" (Facebook)

As a leader, Birchmore echoed the style of her mentors. “If people were goofing off, she’d be like, ‘Come on guys. Gotta focus!’” recalls one former Explorer. But she could also be protective of new recruits. “She would come up to me and she would be like, ‘Hey, you want some extra help?’” says another former Explorer, who was younger than Birchmore.

From the outside, Explorers looked like it was helping Birchmore thrive. In April 2014, her mother sent a letter to the Stoughton police thanking them — and Devine in particular — for all they’d been doing to help her daughter. But over time, Birchmore started to hint at what was going on out of public view.

She told the younger friend from Explorers that she was “kind of talking to” Farwell and they’ve “kind of got a thing going on,” recalls this person. Birchmore said she visited the home Farwell shared with his family at least once a week.

Then there were her stories of flirty exchanges and suggestive jokes in the program. A childhood friend, who was not in Explorers, assumed they involved other teens. Much later, the friend recognized that Birchmore was talking about Stoughton police officers crossing lines, and that Birchmore didn’t seem to understand how wrong that was. “Oh,” the friend finally realized, “She was only happy because she was being groomed.”

As the end of high school neared, Birchmore was so in thrall to Farwell that she happily skipped a rite of passage with her peers to spend it with him. “I loved prom night!” she told him years later in a text. “It was worth not going to prom.”

Farwell wasn’t the only one allegedly crossing boundaries with Birchmore. Over time, the younger friend from Explorers noticed that Devine’s interactions with Birchmore seemed to become flirtatious. “There was always just, like, little comments,” she says. “There would be little giggles exchanged between the two.” (A judge in the family’s civil suit, citing the internal affairs report, wrote that Devine “reportedly began engaging in inappropriate, suggestive conduct with Ms. Birchmore while she was in Explorers.”)

After graduation in June 2015, Birchmore headed to basic training for the Army Reserve — military experience had helped others become police officers. By August, however, she was already back home. She said she’d been kicked out because of her asthma, which she hadn’t disclosed. But she didn’t seem defeated by it.

Friends and family say Birchmore wasn’t the type to linger on failures. She’d just come up with a new plan, then put it into action. With the military path to policing closed, she enrolled in Massasoit Community College to study criminal justice.

She’d stick with it, even through the biggest losses of her life.

The 911 call came in at 4:32 a.m. on May 7, 2016. Denise Birchmore, then 52, had had a stroke. An ambulance sped her to Tufts Medical Center, where the prognosis was grim. Sandra remained “incredibly brave” through the ordeal, says Wright, her cousin. “She was just focusing on her mother and what to do.” Denise died less than two weeks later, five days after her daughter turned 19.

As Birchmore prepared for her mother’s funeral, Claire Gaudet, her grandmother, grew gravely ill. Soon, Birchmore was calling 911. Gaudet, 89, died at Brockton Hospital on June 24, just over a month after Denise.

The deaths of the two women closest to Birchmore left her unmoored and deeply depressed. A source familiar with her journals says her entries from this period expressed suicidal thoughts. For a while, she drank too much, says William Kilroy, her boyfriend at the time.

Despite all Birchmore was going through, she was determined to keep up at school. “Sometimes you see people come through who would crawl over glass to get their education, and she was one of those,” says Aviva Rich-Shea, one of Birchmore’s criminal justice professors at Massasoit. “She wasn’t going to let anything get in her way.”

When Birchmore graduated in 2018 with her associate’s degree in criminal justice, she wore a mortarboard decorated with yellow police tape and the words “CASE CLOSED.”

Sandra Birchmore holds up her degree from Massasoit Community College. (Family photo)

The real world did not bend to Birchmore’s formidable will as easily as her schoolwork did, however. Some who knew her had lingering doubts about whether she’d ever be a police officer. Kilroy suggested she try a related field: She would make a better lawyer than a cop, he thought. “She didn’t have that commanding presence,” he says.

Her boss at a shopping mall, where she worked as a security guard that year, also doubted she could “conduct herself mentally to be in that profession.” He eventually fired Birchmore because she and other employees were flirting and goofing off. Her “sociability” and “desire to fit in” undermined her, says the supervisor.

Braintree police came to a similar conclusion in early 2018 when Birchmore did ride-alongs with officers, to gain experience that might help her chances of eventually joining their ranks.

Birchmore treated the ride-alongs more like gossipy chats than career-development opportunities, according to police emails. She was overly personal with officers, venting to them about troubles with a college boyfriend and coming from a “difficult home,” and she came off “a little strange.”

A sergeant wrote, “I just think she is young, lonely, bored and looking for someone to listen to her.”

Eventually, a lieutenant recommended ending the ride-alongs. He feared Birchmore’s “seemingly poor judgement may place this town, department, and officers in potentially compromising situations.” That was enough for Shastany — who had become Braintree’s police chief after leaving Stoughton.

When Birchmore later inquired about the possibility of internships, or maybe a dispatcher job, she was told nothing was available.

Advertisement

Birchmore’s behavior on ride-alongs alarmed officers in Braintree. In Stoughton, however, where boundaries were often blurred, she appears to have absorbed the lesson that her value for police officers was inextricable from what she could offer them sexually.

Around 2018, Birchmore was driving for Uber. Her friend Hailee Sousa — a younger friend Birchmore took in for a time when she had nowhere else to go — sometimes tagged along. Birchmore liked to have another woman with her, for safety.

She spoke a lot about Matthew Farwell, with whom Birchmore said she was regularly having sex. She told Sousa and others that she sometimes baby-sat for Farwell and his wife. A friend from Explorers recalls that they once drove past Matthew’s house, a green Colonial with a farmer’s porch in Easton. But Birchmore said they couldn’t go in because his wife was home.

She also spoke about William, Sousa recalls, who came across as nicer than his brother in Birchmore’s stories. She described him as a best friend, someone she could turn to for advice when she needed it.

On January 19, 2019, Sousa and Birchmore visited a Stoughton soccer field, which Birchmore said was a regular hookup spot. A few nights earlier, she said, she’d been having sex with Matthew when William drove up. Hearing that, Sousa sent a Snapchat message to her boyfriend: “her bestfriend pulled up on her fucking his brother omg.”

In Birchmore’s telling, Matthew seemed more obsessive than William, and controlling. A friend of Birchmore says he periodically froze her out when she displeased him, blocking her on his phone.

After the soccer field run-in, Sousa says Birchmore “obsessively” messaged Matthew, anxious to know whether he was upset.

A snapchat photo of Hailee Sousa (right) and Sandra Birchmore in 2019.

She also seemed to Sousa to be in endless Facebook chats with a person calling himself Marty Riggs. “She used to speak to Marty Riggs on Messenger, almost all the time, almost every day,” Sousa recalls. She wouldn’t learn his identity until much later.

Around 2019, Birchmore also struck up a friendship with Joshua Heal, a Stoughton animal control officer. She’d met him at the town shelter when she adopted her second cat, Midnight, to keep her late mother’s cat, Lilly, company. After that, she kept returning to the shelter to visit the animals and talk with Heal about her struggles.

“I just happen to be that person that she needed to vent to,” Heal later told Stoughton internal affairs investigators. He knew the Farwells and Devine through work.

Birchmore’s professional and personal losses kept piling up. She’d been studying criminal justice at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, but took a leave in August 2019 after a car crash, and never went back. Looking for a police job in Stoughton, she took the civil service exam and made the list of eligible candidates, but was ranked so far down they never got to her.

That fall, an aunt, Alice M. McKain, died of breast cancer at the family home on Holbrook Avenue, where Birchmore had been living. Her closest surviving relative — her aunt Darlene Smith — eventually decided to sell the house, and told Birchmore she’d need to move out. This led to a blowout argument in May 2020, which ended with Birchmore storming out and her aunt calling 911, worried her niece was going to hurt herself. Birchmore was taken to the hospital, then released when she was determined at no risk of self-harm.

Five days later, records show, an ambulance was called to the home again for a report of a young woman unconscious and possibly suffering from anxiety. She was later transported to a Brockton hospital, the records show. The Globe was unable to confirm further details about the incident.

During her talks with Heal, according to court filings, Birchmore eventually also began to discuss her sexual relationship with Matthew Farwell. At some point, she told the animal control officer she’d also been having sexual encounters with William Farwell and Devine, sometimes in their police cruisers. And Heal, married himself, eventually admitted to investigators that he’d once engaged in a sex act with Birchmore, but insisted it was consensual and never happened again.

Both William Farwell and Devine were arranging to meet Birchmore for sexual encounters by 2020, according to a judge’s summary of allegations in her family’s ongoing civil suit. The judge also reviewed an unredacted copy of the Stoughton internal affairs report and other materials.

By April that year, the judge’s summary says, William was “meeting her for sex in his patrol car and at other places,” and had “encouraged Ms. Birchmore also to have sex with ‘other people at the department.’” That same year, the judge wrote, Devine allegedly “was having full-fledged sexual encounters with Birchmore at various locations.”

When these allegations came to light much later, Birchmore’s loved ones were appalled to learn she was being used in this way by so many men. She was “looking for appreciation, love, listening, compassion,” says a childhood friend. “And every single one of those men took advantage.”

Experts on child sexual abuse see this often, where victims abused by one person will then go on to be used by others, and may even seem to enter into other exploitative relationships willingly — because grooming normalizes those behaviors.

“It is this ongoing process of really confusing and shifting the way someone sees the world,” says Laura Palumbo, communications director at the National Sexual Violence Resource Center. “They have lost their ability to differentiate between what behaviors are healthy and what behaviors are abusive.”

After Birchmore died, Matthew Farwell would make a point of telling investigators about her many sexual partners. A state trooper would twice note this in his reports.

When she was alive, however, Farwell got jealous when Birchmore spent time with others, according to the FBI affidavit. He used rough sex to punish her for bad grades, and for turning off location monitoring on her phone, which he’d demanded she keep on “to gain back his trust for her alleged lies and infidelity,” the affidavit reads.

“I know your hiding shit,” Farwell texted on one occasion, “your location is off again.”

“I’m not doing anything I shouldn’t be,” Birchmore texted in July 2020, around the time the FBI claims he started to seem especially worried about secrecy.

You never knew what iPhones were recording, so you had to be careful, he said: “big brother is always watching.”

On October 5, 2020, Heal shared news with Birchmore that sent her reeling: Matthew Farwell’s wife was pregnant. Their third child was due in four months.

Any surprise Birchmore felt appears to have quickly turned to anger. She texted Heal that she and Farwell had been having sex for “almost 10 years” and that it began when she was 15.

She also shared a note with Heal that she’d drafted for Farwell’s wife: “I am just messaging to inform you that your husband Matthew has been out cheating on you since before you guys were even married.”

Birchmore didn’t send it, however. Instead, she developed a plan.

She had wanted a baby of her own for so long. She’d had at least one miscarriage, according to friends, and that seemed to make her want a child even more. She was starting a new path, taking courses for a career in nursing back at Massasoit. Becoming a mother would complete her transformation.

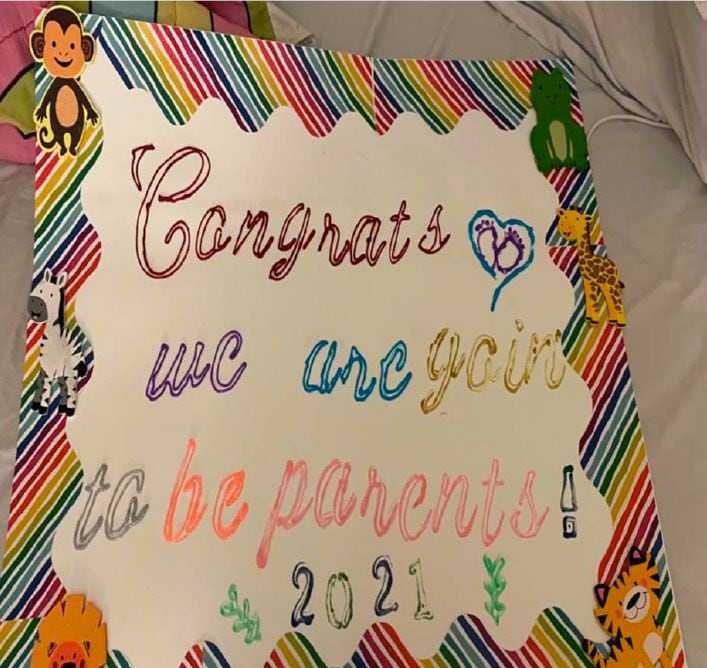

Birchmore sent Matthew Farwell a text message with a photo of a poster that she'd made to let him know that she was pregnant.

The day she found out Farwell’s wife was expecting, Birchmore spelled out what the FBI called an “ultimatum” for him: He would have unprotected sex with her to conceive a child. In return, she would keep the secrets about their relationship.

They both knew she had leverage, and not just because revealing their relationship could blow up Farwell’s marriage. Statutory rape is a crime, and Birchmore and Farwell had texted about them having sex before she was 16.

Birchmore also knew that meeting for sex while he was working could get the police officer into trouble. Ahead of one planned hookup, according to the FBI, she asked him to specify whether he’d be on duty. “Yes,” he responded, “I will be on the clock.”

She photographed her ovulation schedule and sent it to him.

The pair fought bitterly over the terms. Farwell insisted they would have unprotected sex only once, but Birchmore said it had to be more.

After Christmas, Birchmore got the news she had yearned for — she was pregnant. She labored over a handmade announcement. On a poster board, embellished with cutouts of baby animals and two little feet inside a heart, she wrote, “Congrats, we are goin’ to be parents! 2021″

She took a picture and texted it to Farwell.

“I literally have nothing to say right now,” he responded. “How could you express that in a text when I said I don’t appreciate it.”

He wanted to know how far along she was. She seemed to know what he was getting at.

Birchmore had other requests. She insisted Farwell had to put his name on her baby’s birth certificate, though his wife’s baby was arriving sooner. Birchmore’s baby’s “birth certificate is being signed,” she texted Farwell. “Or hers isn’t.” He would need to be there for the delivery, too, and figure out a way to be a real father, because “your kid should matter.”

He replied: “You are truly the worst person on the face of the earth.”

Over the years, some people were troubled by what they were hearing from Birchmore about her life, but they didn’t know what to do about it.

Birchmore’s friend, a former Explorer, says it’s not like she could go to the police. “The grown-ups were all fucking in on it,” she says. “Like, who was I supposed to tell?”

People recall Birchmore resisting appeals to move on from Farwell. “This is how you end up on Dateline,” her friend from childhood warned.

By late 2020, Birchmore tried to reassure some people that she wasn’t interested in a real relationship with Farwell, that he was just a “donor.” To others, it seemed like just the opposite.

She told them Farwell really did love her, and had promised to leave his wife. It just wasn’t the right time yet.

“I think she secretly hoped that he would flip the switch and leave [his wife],” says her childhood friend. “She was Sandra, you know? She was hoping that all the lies he had fed to her since she was 15 years old were going to, you know, finally come to fruition.”

Hailee Sousa, photographed at her home last month, noticed that Birchmore communicated regularly with someone on Facebook named "Marty Riggs." (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Hailee Sousa believes Farwell’s interest was “purely sexual,” and he had no interest in a real relationship. He “completely skipped over [that] she was looking for a romantic interest,” she says.

Sylvie Matte, a cousin, says she tried to get through to Birchmore. “Are you sure you want to be in a relationship with this guy? He’s married. He has kids,” Matte recalls asking. “I was trying to be her conscience a little bit, but I don’t think she heard anything.”

Zatkin, the psychology professor at Bemidji State, says Birchmore’s texts to Farwell reveal, most of all, a desire for commitment. “Clearly to me, it read that her motivations were a relationship with this man, because she thought she had a relationship with this man, right? And if they’ve been having sex for 10 years, that’s not a crazy thing to think.”

From an early age, Birchmore had learned if she needed something, she would have to get it for herself. As the deaths in her family mounted, she must have — at least on some level, Kellie Nee believes — made a realization: I have to find my own way. I have to build my own family.

“She wanted to have her own life,” Nee says. “She wanted someone to love her the way that she needed to be loved.”

On January 20, 2021, one of Birchmore’s friends called the Stoughton Police Department, fuming: Birchmore owed her $248, and hadn’t repaid it, despite promising to. The department employee said it wasn’t a criminal matter, but a civil one — and the police couldn’t help.

That’s when the frustrated friend blurted something out: That Birchmore was having sex with Detective Matthew Farwell.

When the police call-taker told Farwell what she’d said, he angrily ordered that person “not to speak about this to anyone and to never talk about it again,” the FBI affidavit alleges. The call-taker was surprised by his visceral reaction — it was unlike him to act that way.

Farwell texted Birchmore in a rage:

Within just a few days, however, Farwell seemed to have calmed down.

He dropped by Birchmore’s apartment, bringing her ginger ale, and they talked about getting him a key to the unit, even though he’d told her earlier it “wasn’t a good idea.” He also asked her for the access code to her building, making sure it wasn’t unique to her. They’d even started to have a “heart to heart” in her apartment, she told a friend, though it was interrupted when he got called in to work.

On one visit, Farwell spent some time looking around her apartment, inspecting the bathroom and the bedroom closet. Birchmore told a couple of friends that was a little weird. But she was happy his attitude had undergone a complete “180 from where we were at.”

“He’s coming around,” another friend observed.

“A lot more than I thought he was going to yes,” Birchmore replied.

But Farwell wasn’t coming around, according to federal prosecutors. There had been no 180.

FBI agent Chenee Castruita offered another explanation for Farwell’s apparent “shift in demeanor,” she wrote in an affidavit. It “was his attempt to appease Birchmore until he could kill her.”

The agent’s assessment of Farwell’s sudden interest in the bedroom closet: He was casing the apartment.

In her final days, Birchmore was hopeful, and focused on the future. She talked about baby names and visited her hairdresser, who’d heard about her conflicts with the baby’s father. She had lunch with a friend, who then bought her a $200 stroller at Walmart.

When the announcement came through that Sharon schools were closing early because of the storm, Birchmore immediately texted Farwell. He replied that he wasn’t going to be in the area that day.

She told him she wanted him to buy a coming-home outfit for the baby, once they learned if they were having a boy or a girl.

Birchmore had been planning months ahead for the birth of her baby, including looking for an outfit her newborn could wear home. (Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe)

She had a lot to do before then. She bustled around her apartment, doing chores and tapping at her phone. She contacted the photographer about the newborn photo shoot. She chatted with her aunt Darlene, and texted a friend about picking up baby clothes.

She went outside to her car, to get ahead of the snow. The lobby camera captured her coming back inside with her snowbrush at 5:33 p.m.

At 9:08 p.m., Farwell asked if he could “come by for a second” after all. He was already close by: He walked into the lobby a few minutes later.

Less than a week later, Farwell told a state trooper he’d gone there to tell her the baby wasn’t his and to end the relationship — to say “it was all over.”

After 29 minutes, the lobby camera picked up Farwell again, coming off the elevator, passing through the front doors, and walking out into the darkness. In 12 hours or so, his son would be born at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, and he hoped to get there to greet him.

Birchmore did not pick up her phone after Farwell left. She didn’t respond when, at 9:28 p.m., a co-worker messaged her. She left unanswered a text another friend sent just before midnight. Over the next couple of days, calls from Erin Porter, the property manager at her apartment complex, went straight to voicemail. Birchmore never called back.

Everyone who knew her knew that was impossible. Here was a fundamental truth about Sandra Birchmore: If she was breathing, she was on that phone, especially if she had news — good or bad — to share.

It would take more than three years until investigators finally understood her well enough to see that.

Credits

- Reporters: Laura Crimaldi and Yvonne Abraham

- Editors: Francis Storrs and Gordon Russell

- Project managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Craig Walker, Suzanne Kreiter, Pat Greenhouse

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Video producer: Randy Vazquez

- Design: Ryan Huddle and Maura Intemann

- Illustrations: Daniel Stolle for the Boston Globe

- Development and graphics: Kirkland An

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Carrie Simonelli

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Research assistance: Jeremiah Manion

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC