Editing the Constitution

The Constitution is undergoing massive changes in the Supreme Court. It’s time to put the founding document in the hands of the people.

A year before he died, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had a warning for the nation. “True individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence,” he said in his State of the Union address. “People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”

Roosevelt gave that speech in 1944, but he could well have been describing our country today. Thirty-seven million people live in poverty; 64 million families — the bottom half — own only about one percent of total household wealth; 28 million people don’t have health insurance; a few wealthy donors can tip elections in their favor; and, as of this year, the peaceful transition of power is no longer a certainty.

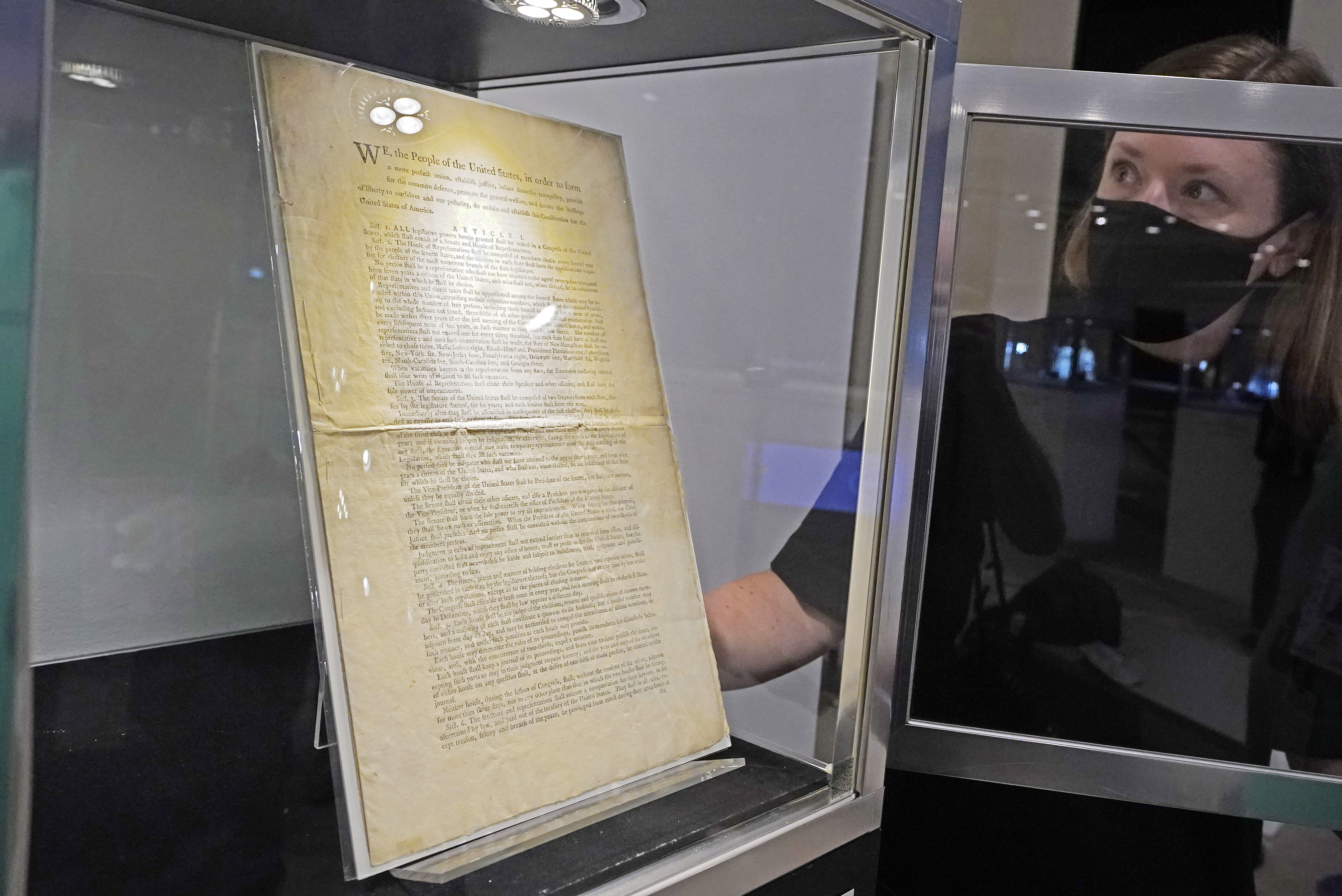

These problems are not independent of one another. Rather, they collectively reflect a government that is failing to deliver sufficient political and economic rights to its people. Some of these rights could be shored up through new laws and social programs. But the rot that is spoiling American democracy has spread from blemishes in our Constitution that we have allowed to fester for generations. If the preamble to the Constitution calls on us to “promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity,” how is it that the freedom of speech applies to corporations in a way that gives them more influence in elections than an actual voter? How is it that the right to vote is not expressly protected in the Constitution? How is it that slavery is still constitutional today if it comes in the form of punishment for a crime?

The Constitution, in other words, is in need of an update. That’s why Globe Ideas has put together this project, in which we asked legal experts, advocates, journalists, and members of the next generation what changes they’d make to the Constitution if they could. It’s a thought experiment to some extent, but it’s also meant to get conversations started about how the Constitution can be the living document it was intended to be.

The genius of the American Constitution does not only lie in its original text; it lies in the people’s ability to edit it.—

Even the Constitution’s biggest fans must admit that the text has key shortcomings. Parts of it are arcane and hard to parse in a modern context (what counts as a “well-regulated militia” today?), and it fails to say much if anything about some important subjects like privacy, health care, and the right to vote. Both problems inhibit progress because they lead to endless arguments over the interpretation of everything from gun rights to campaign finance laws.

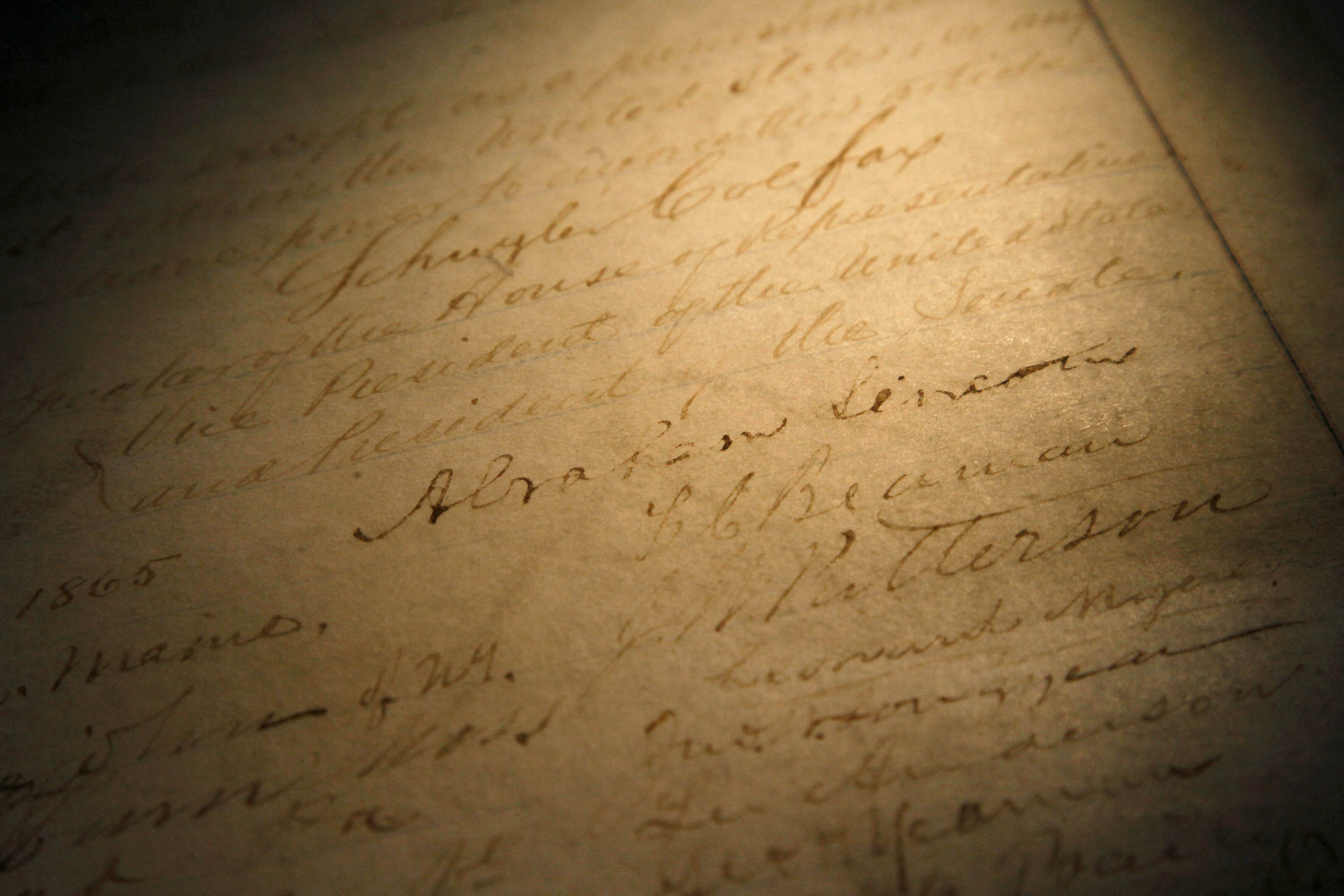

Fortunately, the Founders themselves showed us it didn’t have to be this way. Trying to address some of the deficiencies in the original Constitution, James Madison introduced the Bill of Rights, which was ratified 230 years ago this week. That first alteration enumerated in the founding document some of this country’s most cherished rights. And many decades later, when the nation abolished slavery and expanded the franchise by again changing the Constitution, activists and political leaders were heeding another call in the document’s preamble: That we, the people, ought to form a more perfect union, a goal that requires a never-ending commitment to updating our governing documents.

That work must continue now. In the same speech in which Roosevelt warned about the connection between economic security and the health of our democracy, he went on to argue for what he called a second Bill of Rights — guarantees from the federal government for a base level of economic comfort for every American. Among those rights were health care, employment, housing, social security, freedom from monopolies, and more. Roosevelt did not go so far as to say that these rights required constitutional amendments; they had already become economic truths that the nation “accepted as self-evident” as a result of the New Deal and therefore had to be guaranteed by the government if it sought to truly fulfill the political rights enshrined in the Constitution.

In some respects, Roosevelt was right to omit the idea of amending the Constitution. The nation did, after all, establish a new economic floor, and even the Supreme Court began manifesting Roosevelt’s sentiments in some of its interpretations of the Constitution.

But in other ways, Roosevelt was wrong. In the end, the country did not take his economic truths to be self-evident, even as his second Bill of Rights helped shape constitutions around the world and informed the United Nations’ international standard for human rights. In fact, a sustained effort to roll back the social safety net ensued after his death, and by the 1990s, a president from Roosevelt’s own party vowed to “end welfare as we have come to know it.”

There’s a reason Roosevelt didn’t say it was necessary to enumerate his second Bill of Rights in the Constitution: Amending the Constitution is an incredibly difficult undertaking — one that requires the support of a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress and three-quarters of state legislatures.

But the difficulty of passing amendments should not have stunted Roosevelt’s — or the nation’s — imagination.

When people argue for changing the Constitution, be they liberal or conservative, they tend to be dismissed, even by those who sympathize with their cause. That’s because Americans have reached the point of viewing the Constitution almost as a religious document.

The belief that the Constitution can’t and maybe shouldn’t be changed is so pervasive that unconstitutional ideas are generally seen as not worth putting up a fight for. For example, some 700,000 residents of the nation’s capital remain unequal citizens, paying federal taxes without getting full representation in Congress, all because that’s what the Constitution dictates. For decades, people have sought a convoluted legislative fix for the problem — which, in an ideal world, would be dealt with directly in the Constitution.

But Americans shouldn’t be averse to talking about making changes to the Constitution. Rigid texts, be they religious or secular, have the potential to be misused and to breed extremism. And that’s exactly what’s happening with the Constitution today.

Take a look at the Second Amendment — probably one of the most sloppily written rights ever endowed to a people. There are many people, including conservatives, who believe that the Second Amendment is unclear but too few who speak seriously and earnestly about updating and clarifying it. As a result, the United States has the distinction of having the most heavily armed population in the world.

If you’re skeptical of changing the Constitution — you believe new amendments would be nice, ideally, but aren’t realistic enough to fight for — here’s something to consider: We are already living in an age of profound constitutional change. Except it’s not happening through legislative action in Congress and state legislatures; it’s taking place through judicial interpretations of the founding document in the least democratic branch of government.

In 2008, for example, the Supreme Court fundamentally changed the meaning and application of the Second Amendment in District of Columbia v. Heller, which recognized an individual right to possess a firearm in a 5-4 vote. Before then, the Second Amendment had not been interpreted as the protection of a person’s right to own a gun. In a 1939 decision that was affirmed in 1980, the Court made clear that individuals did not, in fact, have the right to possess firearms that do not have “any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia.” But Heller effectively changed the Second Amendment to mean that a person has a right to keep and bear arms, regardless of whether they are part of a well-regulated militia.

Another example of how the Constitution is quickly changing today is the fate of Roe v. Wade. Itself a landmark decision that was based on shaky ground, it attached the right to abortion to an implicit constitutional right to privacy. That’s why the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued that abortion rights would have been more easily understood and protected had they instead been framed as a matter of equal protection.

Now, Ginsburg’s fears may well be realized. After Texas implemented a law that severely restricted abortion access — one that is a clear violation of Roe and its interpretation of a person’s right to privacy — the Supreme Court refused to block the law, effectively nullifying Roe in Texas. And next spring, the conservative-majority court has the potential to overturn Roe outright when it rules on a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks. Essentially, one of America’s constitutional rights hangs in the balance, and if it’s eroded there isn’t much promising recourse.

Rigid texts, be they religious or secular, have the potential to be misused and to breed extremism. And that’s exactly what’s happening with the Constitution today.—

This is not to say that the Court should never change its interpretations of constitutional rights. To the contrary, landmark decisions are a critical mechanism through which the country can prevent the Constitution from becoming a rigid or quasi-religious text. As then Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in a 1958 decision that deemed it unconstitutional to revoke citizenship as a form of punishment, the Eighth Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment, “must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

By the same token, Americans should always view the Constitution as a document that ought to reflect today’s values rather than those of long-ago, slave-owning men. And if the Constitution is undergoing these massive changes in the courts anyway, why not build movements to update it through amendments that would better articulate Americans’ rights — ones that would better reflect the values of the public?

The Founders had good reason for making our Constitution difficult to amend. After all, if a constitution is too easy to tinker with, then it creates conditions that are ripe for autocracy. One party could win a majority, for example, and quickly change the rules in order to stay in power.

But that doesn’t mean the Founders did not want Americans to change the Constitution ever or at all. Thomas Jefferson, for example, firmly believed that the Constitution ought to be amended at regular intervals so that it could “be handed on, with periodical repairs, from generation to generation, to the end of time.” And liberal democracies outside the United States, such as those in Western Europe, amend their constitutions much more frequently in order to adapt to modern times without sacrificing their stability.

There is no denying that new amendments have little chance of passing given today’s political landscape. But even so, we should always be thinking about how to improve the Constitution rather than dismissing the idea altogether. Amendments have almost always required time and a crusade: In 1848, at the Seneca Falls Convention, the right to vote was propelled to become a central tenet of the women’s rights movement. Thirty years later, the first women’s suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress. But the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote, did not become law of the land until 1920. Who knows what the government’s makeup will be in 20, 50, or 80 years? If it’s hard to imagine that more amendments will pass even then, not trying all but guarantees that they never will.

In the end, the genius of the American Constitution does not only lie in its original text; it lies in the people’s ability to edit it. That’s how Americans got their first Bill of Rights. It’s how slavery was abolished. It’s how women got the right to vote. And it’s how we, the people, can secure a more robust, equal, and just democracy for posterity.

Abdallah Fayyad can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @abdallah_fayyad.