Tyla Ordonez (left) and Skye Foote sat at the grave site of their friend G Araujo in Gloucester. Araujo died in 2018 after running away from a group home. (Erin Clark/Globe staff)

600 kids go missing from state care a year. These are the lost children of Massachusetts.

There was only one bed available at Pathways, a Bradford group home for teens in crisis, when a state worker secured a spot there for G Araujo.

The home was supposed to be a haven for the vulnerable 17-year-old from Gloucester.

Araujo had begun gingerly embracing a gender transition, experimenting with makeup and women’s clothing, while leaning away from her birth name, Gustavo. At the same time, her home life was strained, and she struggled with drugs. Placed in a foster home, she kept missing curfew. The foster parents worried she needed more supervision than they could provide.

Araujo was uneasy as she arrived at Pathways and grew more so in the coming hours. The next day, she told staff she felt lonely. Repeatedly, she said she wanted to run and use drugs.

Yet her distress did not set off alarms. No one notified the home’s on-call administrator, who could have ordered crisis intervention for the teen.

That night, Araujo ran.

Two days after that, she was found dead of an accidental overdose following a house party, surrounded by drug paraphernalia and an empty bottle of alcohol.

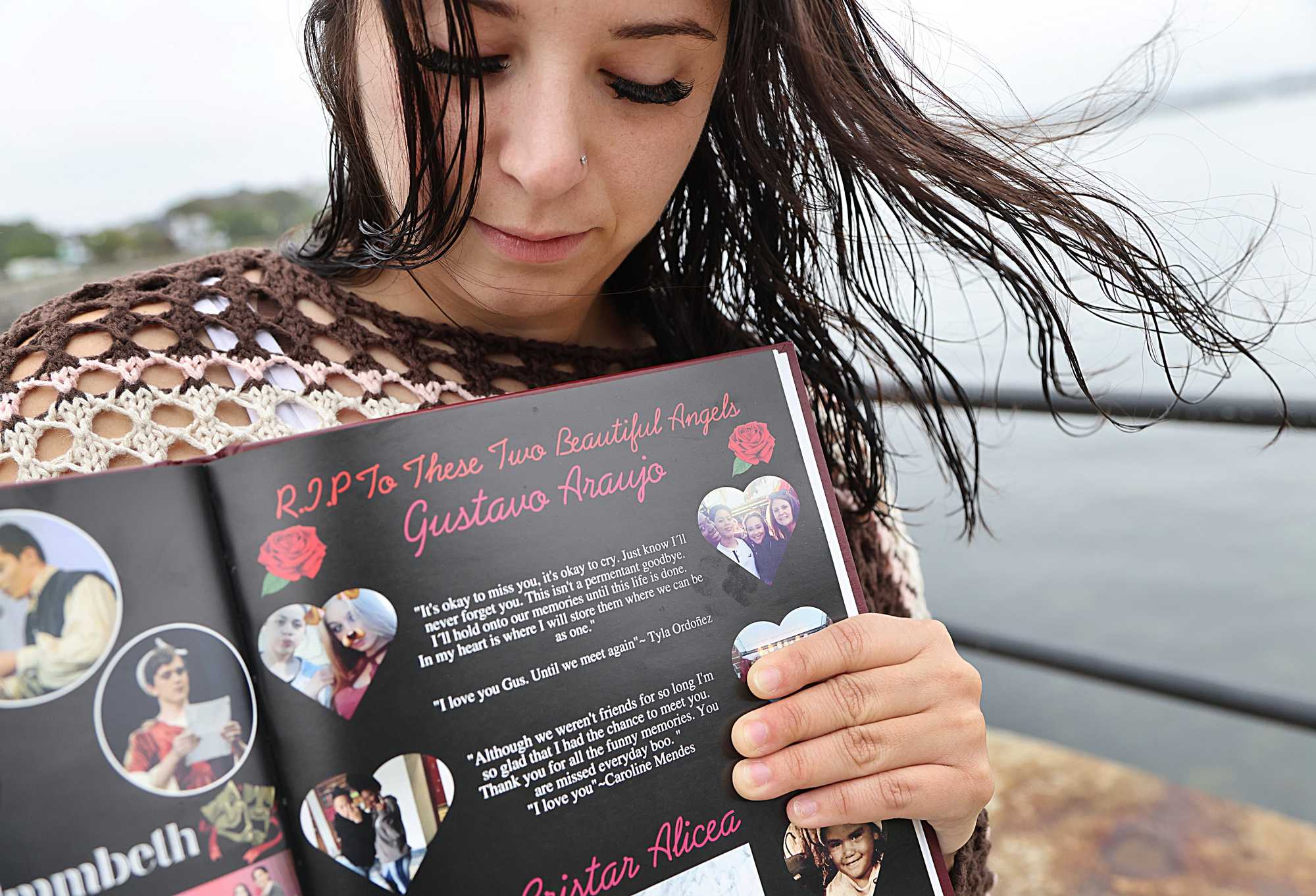

Alexia Thompson held a Gloucester High yearbook open to a page memorializing her friend G Araujo, who died after running away from a group home. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

“I read it as a cry for help,” Alexia Thompson, a friend of Araujo’s since middle school, said after reading the state’s report on her final days. “And they really weren’t seeing that.”

Araujo’s 2018 death, never before reported, represents the most alarming outcome of a near-daily occurrence for children in Massachusetts’s care. They run away. They go missing. And the consequences can be dire.

Some return quickly, while others spend weeks or months on the run. Others are never found. While gone, many are lured into the world’s darkest corners, becoming victims of sex trafficking.

The draw of those dangerous relationships can be strong.

“If you’ve been in and out of the system all your life, at 16, 17 years old you don’t feel like a person,” said Audra Doody, who was exploited as a teen and is now an advocate for women hoping to escape the sex trade. “Someone who offers clothes and makeup? You step into a whole different world. It is like a family.”

Kids in the custody of DCF, in particular those placed in group homes, are among the state’s most vulnerable. Many come from shattered homes or difficult circumstances. They carry extraordinary burdens. And the social service safety net too often fails them.

The Globe reviewed dozens of investigations from the past decade involving kids who went missing from group homes. In numerous cases, lax supervision, poor training, or other lapses by staff contributed to a child’s flight.

The cases identified by the Globe include a young boy who despite chronic running was left unsupervised only to leave again; two children who fooled staff by stuffing pillows in their beds and fleeing out a window that was supposed to be locked; and teens obtaining contraband cellphones and sneaking out for all-night parties.

Staverne Miller, commissioner of the Department of Children and Families, noted in an interview with the Globe that group homes are not locked facilities and said her agency is responsible for a population that is at a high risk of running.

Advertisement

Mary McGeown, undersecretary for the Office of Health and Human Services, said running is “their way of dealing with grief, of dealing with conflict, fear.”

“All of these kids have experienced trauma,” she said.

Miller said the agency created a missing or absent unit as a pilot in 2019 and expanded it statewide this year. She said that team has built bridges with children who otherwise might have been completely out of touch with the state agency. Due to their work, Miller said, DCF is “in contact” with roughly 80 percent of missing kids.

Agency officials, however, wouldn’t say whether “in contact” meant speaking with a child daily, monthly, or less often than that. And they provided no evidence that those kids are being returned to care more quickly.

Federal data show scores of Massachusetts kids go missing from state care for three months or longer every year.

“Their work is not to prevent them from going missing at all,” Miller said of the missing kids unit. “The work is, once they are missing or absent, to help us to locate them and to prevent them from running in the future.”

Their experiences can be haunting.

In a 2021 case from Springfield, a 13-year-old girl using a cellphone unnoticed by staff asked a 48-year-old man for a ride to Boston.

“I’ll bring you to Boston,” replied the man, Carlos Casillas, court records show, “if we do something first, baby.”

The next day, Casillas told the teen he was nervous about picking her up outside the group home. But the girl had fled before and wasn’t concerned.

“Start to run,” he texted once he had pulled onto the street.

She darted into his sedan. He took her to a motel.

Last year, Casillas was sentenced in federal court to 18 years in prison for sex trafficking of a minor.

The Springfield home where the teen stayed, Greylock, closed earlier this year after a worker was charged with repeatedly raping a child living there. A Globe investigation in June identified 10 credible reports of child abuse or neglect among dozens of instances of child mistreatment at Greylock since 2019.

The Greylock youth home in Springfield, pictured in February, shortly before it closed. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

Greylock was among the most-cited homes in the state, but a few others were worse, state inspection records show. Over the past five years, 10 closed after extensive violations, according to the Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care, which licenses group homes.

Charles Lerner, director of the Massachusetts CASA Association, which supports children with DCF cases, said too often people cast judgment on the young people who run rather than on the system that drives them to flee.

“It just might be because we’ve done a really crappy job as their custodian,” he said.

‘I ran from her out of fear’

The child welfare system in Massachusetts is under strain. The state has among the highest rates of abuse or neglect committed against children in care, is more likely than other states to bounce kids between placements in their first year, and relies more heavily on group homes.

Those trends exacerbate the state’s struggles with kids going missing. Research shows children are more likely to run if they’ve cycled through multiple placements or have been placed in group settings rather than with a foster family.

All this occurs despite relatively robust state spending. Massachusetts is one of only 11 states that spends over $1 billion on its child welfare system, 2022 data show. And of those states, Massachusetts has the smallest child population.

That money fuels an agency with extraordinary authority. DCF investigates allegations of child abuse or neglect and can work with families, or, if the agency determines it’s unsafe for a child to remain in the home, seek to break them up. The agency had oversight of nearly 39,000 children at the end of 2023, one in five of them separated from their parents.

Most of these kids end up in foster homes or with relatives. But among teenagers, well over a third are sent to residential facilities, including the state’s roughly 130 group homes, a recent DCF count showed. At their best, group homes offer therapeutic environments for young people exposed to severe trauma and mistreatment. All too often, though, advocates and former residents say, they fall far short.

Destiney, 26, of Holyoke, told the Globe she entered the child welfare system at age 9 and frequently ran away. At first, she said, she took off to be near her mother, though she struggled with addiction and had exposed Destiney to the sex trade. By 12, she herself was being sexually exploited.

“I very much felt like I had the control,” said Destiney, who asked that only her first name be used to protect her privacy. “That was a very, very large factor for me.”

Destiney recalled group home staff making light of how often she ran away, nicknaming her “Happy Feet.”

Miller, the DCF commissioner, said that the state aims to place children in the least restrictive setting possible and called residential homes a “last resort” for those with complex needs. She said group home workers are “up to the task.”

But state records from the past decade show numerous examples of group home staff falling short, giving children the opportunity to flee.

Advertisement

At a Jamaica Plain group home for young children in 2018, a boy who was known to run when frustrated was left alone to calm down from a fight. Without supervision, he took off again. State investigators found that while the boy had escaped or attempted to at least 10 times in a year, the home never created a plan to address his chronic running.

At a Falmouth group home for teens, investigators documented numerous alarming incidents over five weeks in 2017, including residents obtaining cellphones to send explicit messages and leaving for all-night parties. The investigators found staff had no guidance on preventing residents with histories of sexual exploitation from habitually running.

At an Ipswich home for adolescents the same year, the state found more than a dozen violations after two children escaped out a window in the middle of the night and snuck back in without staff noticing. A supervisor who later tried escaping out of the window told an investigator, “I did it in 10 seconds.”

Advocates say the conditions within group homes are a key driver of why so many children run.

“We were always lucky when we could get kids into one of the group homes that had really strong reputations,” said Carol Erskine, a retired Worcester County juvenile court judge. “There just aren’t that many that fit into that category.”

Alexia Feliciano, 18, said she ran from a DCF employee in June 2023 rather than be taken back to a troubled group home in Springfield where she had been assaulted by an employee.

Alexia Feliciano said she ran from her Department of Children and Families social worker rather than return to a group home where she said she was physically abused. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Maple Home, a group home in Springfield, closed last year after being cited for numerous violations by the state. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Eight months later the residence, Maple Home, would close. Among the string of alarming violations found there by state investigators: Staff punched and spit on residents; employees failed to report potential abuse in violation of the law; and the home was unsanitary and unsafe, with windows on upper levels open and missing screens, a mattress sitting on the floor, and sheets used as curtains.

Once, Feliciano remembered, she called 911 from the home to report that staff there were physically abusive. A dispatcher asked to speak to an employee, who assured him Feliciano was overreacting, then ended the call.

Audio from the call, obtained by the Globe through a public records request, matches Feliciano’s recollection.

A spokesperson for Gandara Mental Health Center, the nonprofit that operated Maple Home, declined to comment.

Feliciano said she pleaded with her social worker not to be taken back to a place where she’d been traumatized.

“She told me, ‘We have nowhere else for you to go, Alexia. You have to go. Get in the car,’” Feliciano recalled.

Instead, she bolted.

“I ran from her,” she said, “out of fear for my safety.”

Counts underestimate problem

By the state’s tally, hundreds of kids go missing each year. But that understates the true scale of the problem. In reality, some programs operate in a constant cycle of residents running and returning, police call logs show, a reality DCF data don’t capture.

For instance, in 2023, an Ashland group home called police five times in a week to report a missing kid, even once calling about a new runaway before the previous missing child had returned. From 2019 to 2024, the residence reported a missing kid to police more than 150 times. DCF recorded just 29 runaway incidents.

Another group home in Fitchburg reported a missing child to police at least 60 times in six years. DCF data show nine such incidents.

By way of explanation, DCF officials said that while case workers keep notes on all kids who go missing, the official tally may not include those missing only briefly. It also does not include kids who leave and return while their social workers are off duty, even if the child was gone for an entire weekend.

But even short periods on the run can have dire consequences.

Iliana Beltzer, 23, of Worcester, said she often ended up in dangerous situations when she ran from the group homes where she spent much of her adolescence. Once, she recalled fleeing to New York City when she was 17; within four days she had been solicited for sex and sexually assaulted. Another time, she fled a Rutland group home for Brockton. Having nowhere to sleep, she went home with a worker at an area bar. She felt trapped and assumed he would kick her out – or worse – if she didn’t have sex with him.

“I figured if I said no, he was just going to do it anyway,” she said.

Despite the dangers, Beltzer said, running often seemed more appealing than staying in a home.

Advertisement

She recalled a teacher at the Walden Street School, a group home in Concord, who touched her inappropriately. The teacher, Francis Castillo, is awaiting trial on charges that he repeatedly sexually assaulted a teenage student at a school in Providence, according to court records.

A spokesperson for the Justice Resource Institute, a nonprofit that operates 10 youth homes in Massachusetts, confirmed Castillo had worked at Walden Street for about eight months but said she could not disclose the circumstances of his 2020 departure. A person with knowledge of the case said Castillo was fired for inappropriate conduct, and his behavior was reported to both DCF and local police. Castillo, whose declined to comment through his lawyer, has not been charged in that case.

‘All of our best friend’

The Bradford group home Araujo ran from, a white triple-decker that faces a strip mall, was intended for adolescents in crisis.

Araujo learned she was being moved there on a Friday with just a few hours notice, according to Michelle Lipinski, principal at Northshore Recovery High School. Araujo had attended the small alternative school for a few weeks and blossomed during that time, Lipinski said, using her birth name when she arrived but soon adopting female pronouns and asking to be called G. She recalled it being “beautiful to watch a person find themselves.”

Lipinski said the teen was upset about the move to Pathways.

“She was going from a foster home to a group home,” Lipinski said. “And that’s a hard switch.”

G Araujo is pictured in a photo posted to her Instagram account on Aug. 17, 2018, two months before her death.

When she arrived at Pathways, Araujo was so distressed that a worker there decided to skip a standard questionnaire about the new arrival’s history, a state investigation documented. Araujo was also “immediately uncomfortable” with her room assignment, which was with a person of the opposite gender, the investigator wrote. The nonprofit, in a statement, said Araujo was placed with another transgender youth. The investigator called it an “inappropriate” fit.

Araujo told an employee she did not like the person’s “vibe.” The next morning an argument between the roommates grew so volatile that staff had to restrain Araujo. Later that day, Araujo tearfully told an employee that she felt no one wanted her.

Workers offered distractions, getting permission for Araujo to attend a movie with her peers and gathering residents for a beauty group when they learned she enjoyed cosmetics. Araujo seemed to appreciate the staff’s kindness, according to the state’s investigation, but continued to struggle.

Numerous times, she told employees she wanted to run and use drugs.

A state investigation concluded staff should have notified the home’s on-call administrator about the teen’s precarious state and provided crisis intervention. The administrator later told an investigator that if they had been contacted, they would have considered having the teen psychiatrically screened.

Instead, around 7 p.m., Araujo persuaded a worker to give her back her cellphone. Araujo’s intake paperwork said she had a history of running, especially if she had access to social media. She went outside to make a call.

From there, she took off.

Though staff should have notified police immediately, the call didn’t go out for more than an hour. That evening, the home’s administrator learned of Araujo’s distressing statements and drafted a safety plan for when she returned.

On Monday morning, Araujo was pronounced dead at a house in Billerica, about 25 miles away. According to death records, she died from a mixture of prescription medications. She and two other teens who had separately gone missing from Pathways had been there for a party, where people had gathered to watch the Red Sox win the final game of the World Series, according to police and state records.

In a statement, Amy Kershaw, commissioner of the Department of Early Education and Care, called Araujo’s death “heartbreaking and unacceptable.”

Over the ensuing months, state regulators kept a close eye on the nonprofit that operates Pathways, NFI Massachusetts. That spring the nonprofit agreed to administrative reforms across its group homes, according to the Department of Early Education and Care. Within the next year, NFI fired two employees at its Pathways group home, one accused of buying alcohol for residents and another accused of being in an inappropriate relationship with a resident, investigative records show. The investigators found that both employees had received prior warnings about keeping appropriate boundaries with kids.

The nonprofit closed Pathways in 2021, citing staffing shortages, then reopened it in Amesbury in 2023.

In a statement, the nonprofit’s executive director, Eric Klingaman, said Pathways cares for among the most challenging youths, including those “whose behaviors cannot be managed elsewhere.” He said there has been a “precipitous drop” in missing child reports at Pathways since it reopened. He pointed to new activities to engage residents, enhanced training for staff on addressing trauma, and increased wages.

“The loss of any young person is deeply tragic,” he said of Araujo’s death.

At her funeral, Araujo’s casket was open, her makeup wiped clean and face once again boyish. Her nails were still painted black but clipped short.

Friends Tyla Ordoñez (left) and Skye Foote wore shirts honoring G Araujo, a teen who died in 2018 after running away from a group home where she had been placed by the Department of Children and Families. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Childhood friends said they hadn’t known how deeply Araujo was struggling. They remember their friend instead as outgoing and quick to make others laugh. Asked to read a passage during class, Araujo would break into a dramatic rendition. The friends loved acting out scenes from “High School Musical,” with Araujo insisting on playing Sharpay, a teen who masked her insecurity with a shield of confidence.

Skye Foote and Tyla Ordoñez still regularly visit the grave in Gloucester where Araujo is buried beneath a plaque bearing her birth name. Foote recently decorated the site for fall, planting mums and swapping out the vases of fake flowers for ones in hues of deep red and yellow. Often, she sees newly left trinkets and knows others have been visiting, too.

Araujo, she said with a laugh, “was all of our best friends. We would all fight over who was the best friend.”

Ordoñez said she thinks often about still having Araujo in her life, ordinary moments like making dinner together and watching Araujo play with her 3-year-old son. When she slips into seeing an older version of the boy she grew up with, she catches herself, straining to envision the person her friend would be today.

G Araujo’s gravesite in Gloucester is adorned with seashells, flowers, and candles. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Development by John Hancock. Graphics by John Hancock and Scooty Nickerson. Quality assurance by Nalini Dokula. Tricia L. Nadolny can be reached at [email protected]. Jason Laughlin can be reached at [email protected]. Scooty Nickerson can be reached at [email protected].

Advertisement

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC