Over the past two decades, a sea of asphalt on the South Boston Waterfront has transformed into the Seaport, a bustling neighborhood full of office buildings, shopping, and high-end housing that has powered the city's tax base. But its prosperity is at risk due to rising seas. (David L. Ryan/Globe staff)

Water is coming for the Seaport; the whole city will be poorer for it.

Buildings in the Seaport fund one-tenth of Boston’s property-tax base. Flood waters and sea level rise will soon put that at risk.

Nearly half a century ago, Boston’s civic leaders faced a choice.

The city was nearly bankrupt, but the Big Dig and Boston Harbor cleanup promised to transform downtown. Just across Fort Point Channel sat roughly a thousand acres of parking lots and old warehouses on which developers were eager to build.

Read more

- If Massachusetts can’t fix floody Morrissey Blvd., how will it keep all our roads and rails dry?

- Behind the levee: The forgotten communities at risk in Massachusetts

- Small towns, high tides: Across Mass., coastal communities grapple with rising seas.

- Hull or High Water: When climate change hits home

- Interactive map: Do you live in a flood zone?

Yes, those parking lots sat on filled-in mud flats just barely above sea level. Even in the 1980s, there were worries about storms and floods and melting ice caps, but the effects seemed far in the future. In the near term, a small old city that needed tax revenue fast had open land and the will to transform it.

What became the Seaport was born, and it helped usher in a period of unprecedented prosperity for Boston. Today, that thousand acres is home to white-shoe law firms and white-coat-wearing scientists, multimillion-dollar condos with stunning harbor views, beer gardens, and high-end boutiques. Nearly $20 billion worth of real estate, in all.

Last year, those buildings together generated $343 million in property taxes for Boston, according to a Boston Globe analysis. That’s about 10 percent of the city’s tax base, from less than 4 percent of its land. (The estimate does not include residential exemptions for homeowners.)

What's now the Seaport, in 1984. (Bill Brett/Globe Staff)

The Seaport’s taxes enrich every corner of Boston. For context, $343 million is enough to fund the city’s Public Health Commission two times over. It’s nearly three times the budget for Public Works, which keeps streets clean and potholes filled. It would pay a year’s salary for every police officer patrolling Boston’s streets.

“You could make the case that the Seaport has become a cash cow for the rest of the city,” said Larry DiCara, a former City Council member.

That cash cow, however, is increasingly at risk. Rising seas threaten to reclaim those old mud flats, and, together with more frequent and severe storms, could swamp the neighborhood that has risen atop them. In all, 99 percent of what’s been built in the Seaport in the last quarter-century is at risk of flooding by 2050, according to a recent analysis from the Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

A flooded sidewalk off Congress Street along Fort Point Channel, in 2018. (John Tlumacki/Globe staff)

Even if the buildings are designed to withstand flooding — as many are, their developers stress — the streets and tunnels that connect them to the rest of Boston are vulnerable. Sea water coursing down Seaport Boulevard and storm drains spilling up onto Northern Avenue will inevitably make even the best-designed condo tower hard to reach, the swankiest restaurant unappealing. As waters keep rising, the value of those buildings could decline, and with it a tax base that pays for services all over Boston.

In that sense, the mistakes of the Seaport will cost us all.

“Everyone knew that there was a risk in developing that area,” said longtime civic leader Ted Landsmark. The question, then, was how to balance that risk while wringing out as much benefit to Boston as possible.

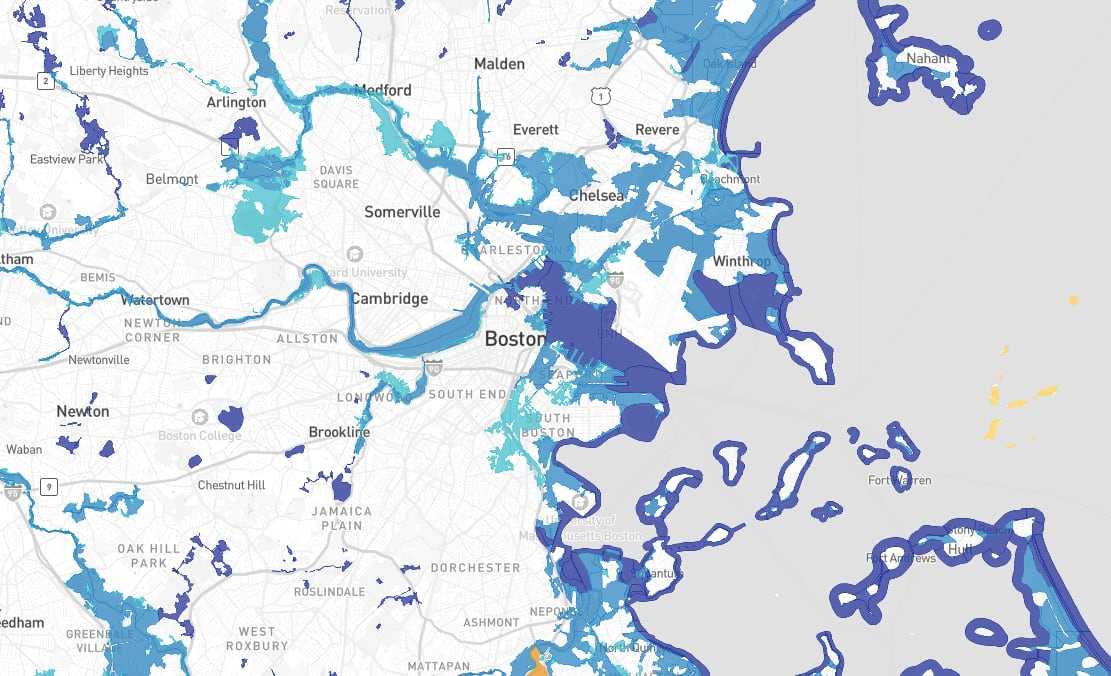

- 100-year flood plain

- Regulatory floodway (100-year)

- 500-year flood plain

- Undetermined flood hazard

- Area not included

A modern dilemma

Many of Boston’s low-lying waterfront neighborhoods sit in flood plains. One of every seven Bostonians — about 100,000 people — will be exposed to flooding as soon as the 2050s, according to estimates from Arup, a multinational engineering consultancy. In downtown, East Boston, South Boston, and the South End, flooding could force about 9,000 people to leave their homes and seek public shelter.

While many of those neighborhoods were built more than a century ago, much of the Seaport is a modern creation.

The easiest way to protect the Seaport from flooding would have been early on, and all at once, said Paul Kirshen, a University of Massachusetts Boston professor who has spent decades researching climate change and coastal management. Safeguards such as elevating the whole neighborhood or building sea walls around it were contemplated but ultimately nixed as too expensive.

The Moakley Federal Courthouse, and behind it Fan Pier, were the first big developments to go up in the Seaport. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

In the late 1980s, the state planned for sea level rise at the Deer Island sewage treatment plant in Boston Harbor by raising portions of the facility nearly two feet. And yet a decade later, when the Moakley Federal Courthouse opened in the Seaport, it was not elevated. Today, the facility’s multistory wall of glass offers eye-popping downtown views, while its harborfront path is often splashed by sea water.

At the time, the courthouse’s planners spoke of its economic impact and architectural beauty. Rising seas simply weren’t on the radar, said Vivien Li, a longtime advocate for public access to the waterfront.

Shortly after the courthouse opened in 1998, The Fallon Co. proposed what would become the Seaport’s first large-scale mixed-use project: Fan Pier, a nine-building, 3 million-square-foot development that would cement then-Mayor Thomas Menino’s ambition for an “Innovation District” to rival Cambridge’s Kendall Square. It took another dozen years to land Vertex Pharmaceuticals as a tenant. By then, the Seaport’s building boom was on.

“They wanted to get the projects underway,” Li said. “And climate change seemed to be a long ways away.”

But as the Seaport expanded, so too did recognition of climate risk. In 2010, Menino launched the Green Ribbon Commission to study Boston’s vulnerability.

A woman watched as waves crashed into Fan Pier in the Seaport District during a nor'easter on March 3, 2018. (Keith Bedford/Globe Staff)

That vulnerability was made especially clear in 2018, when back-to-back nor’easters submerged stretches of Seaport Boulevard. To some, video of a dumpster floating through an alley off Farnsworth Street symbolized the hubris of building so much, so quickly, so close to the sea.

Kairos Shen, Menino’s chief planner who returned to that role last year under Mayor Michelle Wu, said it was often difficult in the Seaport’s early days to convince a skeptical real estate development industry that climate protections were worthwhile investments. Though the city pushed developers to build more protections than what the law required, climate science was also not as advanced as it is today.

“I’m not excusing that,” Shen said. “The practice that we were pushing in the Planning Department was the best knowledge that we could get agreement on.”

Advertisement

The Seaport’s growth, and benefits

For Boston, going all-in on the Seaport — adding essentially a third downtown neighborhood in less than 20 years — has led to immense growth in tax revenue, with property taxes ballooning to 16 times their prior value, a Globe data analysis shows.

After Vertex moved in, a wave of companies followed — from Amazon to Reebok to now Hasbro — bringing thousands of good white-collar jobs. Those workers fill the restaurants that line Seaport Boulevard, and some of them rent apartments that fetch $4,000 a month or more. On weekend nights, 20-somethings pack The Grand nightclub and toast on the roof-deck bar at The Envoy hotel.

All those buildings pay far more in taxes than the warehouses and parking lots they replaced. Consider a low-slung building on Fid Kennedy Avenue that was once a bakery and corporate office for Au Bon Pain.

An under-construction condo building on Pier 4, reflected in the windows of a new office building, in 2018. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

In 2019, as Au Bon Pain was winding down operations, the building owed around $36,000 in property taxes. The next year, development firm Marcus Partners paid $25 million to acquire the site and then built an eight-story life-science lab. Today that building is leased to Gingko Bioworks, a biotech company, and this year the tax bill will total nearly $3.7 million.

That’s nearly enough to cover the city’s portion of the Boston Public Library’s annual book-buying budget, which has grown around 85 percent since 2010, said Melissa Andrews, the system’s chief of collection management. The library system needs more money if it hopes to serve the needs of its many readers across 26 branches.

One of those readers is 77-year-old Marie-Lourdes Jean-Jacques, who comes to the Mattapan branch nearly every day. Originally from Haiti, she checks out books in English and French, and recalls the branch’s construction 16 years ago. The library gives a place for respite, community, and family, she said. On a recent weekday afternoon, Jean-Jacques spoke with her granddaughters Janaysia and Olivia, who came by after school, before pulling out a laptop for a video call.

For all the critiques of the Seaport as a playground for wealthy, mostly white renters and corporate workers, the kind of tax revenue it generates also helps fund resources to help people stay in Boston, including a downpayment assistance program the city launched nearly 30 years ago that gives out $4 million a year in grants.

Jorgelina Uribe, a doctoral student at UMass Boston and administrator at Northeastern University School of Law, used around $15,000 from the program to buy a subsidized condo on Williams Street in Jamaica Plain for herself and her 3-year-old daughter. Uribe grew up in the South End, served with AmeriCorps at The Curley school on Centre Street, and always dreamed of living in JP.

“I certainly would not have been able to buy without the down payment assistance,” she said. “It was kind of surreal to be like, ‘I just bought a condo in JP,’ which I thought last year was absolutely impossible.”

Advertisement

‘Water deep enough for people to kayak through’

For real estate developers working in Boston, Hurricane Sandy was a wake-up call. After the 2012 storm walloped Manhattan, flooding data centers and office buildings, leaders here were struck — their buildings were vulnerable, too.

In the aftermath, many Seaport developers refashioned their buildings, moving electrical infrastructure from basements to the upper floors. They elevated whole sites and invested in rapidly deployable flood barriers to protect the entrances of underground garages and other vulnerable spots. Some even designed their first floors to be re-installed after damage from a foot or two of floodwater.

“Every new building that’s built in the Seaport is arguably one of the most resilient buildings in the country, based on how forward it is looking,” said Boston climate chief Brian Swett.

In 2021, Boston wrote flood resistant design into its zoning code, requiring many of these things in new construction. It remains the only large city in the US to do so, Swett said. Of course, by 2021, much of the Seaport had already been built.

The property-by-property approach taken since the late ’90s could soon effectively lead to a patchwork of islands surrounded by flooded streets, said Derek Anderson, who leads civil and water work in Boston for Arup.

“It would be water deep enough for people to kayak through,” Anderson said. “When private developers say, ‘We’ve made our buildings resilient,’ they’re not talking about making the neighborhood resilient.”

Deployable barriers protected the MBTA's Aquarium Blue Line station on Long Wharf ahead of a nor'easter earlier this month. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

Now, finally, the city has begun to erect broader defenses.

From the North End to Dorchester, waterfront parks and playgrounds are being elevated and protected to, in turn, stand as a first line of defense for whole neighborhoods behind them. The city is racing to protect vulnerable stretches of property in five waterfront neighborhoods where flood damage as early as 2030 is predicted. Boston has $150 million in its budget for initiatives to reduce coastal flood risk.

The city is investing more into projects incorporating coastal resilience than it has in its history, said Chris Osgood, who leads Boston’s office of climate resilience. His office has been working with the US Army Corps of Engineers to craft a plan to protect waterfront neighborhoods. They hope to have it ready by 2028.

Jeff Herzog, program manager for the Army Corps’ New England District, said he’s seen few cities across the country as focused on the issue as Boston. That focus is crucial, given that the Army Corps project likely won’t even break ground until around 2030.

“Some of these flood pathways are anticipated to be a problem by 2030,” Herzog said, “so it’s important to start today to prepare for those immediate, near-term risks.”

It’s too early to know how much the broad Army Corps plan might cost, though it’s likely to be far beyond what Boston alone can pay. Help from the federal government, of course, would need to be approved by Congress, and that’s hard to rely on right now. The Trump administration has already begun cutting federal grant programs that aimed to help bolster climate defenses, including $35 million in funding that was to go toward projects in South Boston and Dorchester.

Money may be more likely to come from state and local government and private developers. The city’s Climate Resiliency Fund, for example, launched in 2021 by asking developers to voluntarily match city investment toward protections like flood berms in the Raymond L. Flynn Marine Industrial Park.

A sea wall on Shoreline Road in the Seaport District. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

It’s a smart idea, said Anthony Flint, a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in Cambridge, one that builds on mutual interest to help keep the Seaport ahead of rising seas.

“The owners want the asset to stay dry,” he said. “And the city wants to continue getting the tax revenue.”

But four years in, the city has not yet activated the fund. While several developers have budgeted for the program, no one pays in until owners of 50 percent of the real estate in the district agree; they’re at 34 percent now. Four lab projects that would get closer to that threshold are stalled amid a broader slowdown in new development.

That highlights one challenge of relying on new development to finance climate defenses. Development sometimes slows down, but sea level rise won’t.

Advertisement

‘It’s not something I think about’

On a recent evening, Seaport Boulevard and Congress Street buzzed with an energy that didn’t exist 20 years ago. Runners curved around the Harborwalk while conference-goers still wearing nametags settled in for dinner and drinks at waterfront restaurants. Young professionals walked their dogs or lugged bags of groceries from Trader Joe’s.

One of those young professionals, Alexa Ferreira, was out walking her 4-month-old cavapoo, Teddy. Ferreira, who has rented in the neighborhood for three years, said she notes the high tides when water creeps up the amphitheater-style steps outside the Pier 4 condo building, which are designed to accommodate the ebbs and flows of the tide. But generally, flooding’s not on her mind.

“I don’t own and am probably not going to be here long term,“ she said. ”It’s not something I think about.”

Renters may not always be contemplating sea level rise, but the companies that own the neighborhood’s billion-dollar buildings — and the watchdogs supervising Boston’s fiscal health — are beginning to.

Pedestrians along Seaport Boulevard on a winter afternoon in 2023. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

The Harborwalk along Fort Point Channel. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

In May, when S&P Global Ratings reaffirmed the city’s AAA bond rating, it added a warning about Boston’s perch at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean: “significant portions of [Boston’s] tax base are in areas prone to flooding or projected to be exposed in the coming years.”

Landlords are also taking note. Alexandria Real Estate Equities, a major developer of life science lab space, acknowledges that climate change poses many risks to its portfolio, which includes buildings in waterfront communities from Boston to San Francisco. Those risks range from construction delays to reduced tenant demand to, as it says in its recent corporate responsibility report, “our inability to operate the buildings at all.”

One flood likely won’t swamp Alexandria’s bottom line; like many big property owners, the firm hedges weather risk by insuring its buildings in big, diverse portfolios. It, too, has installed site-specific protections, like elevating the ground beneath the $700 million research lab it built for drugmaker Eli Lilly along Fort Point Channel.

But despite that, Alexandria warned that climate change could outstrip its efforts. “There can be no assurance that our insurance will cover all our potential losses,” the report noted.

Owners of far smaller businesses are also eyeing the water.

Larry Jimerson runs a barbecue joint on a plaza off D Street where he moved from Chelsea in 2012. He remembers the 2018 storms, how the water made the sidewalks and streets outside his business impassable.

“Water is one of those things — you just can’t mess with it," he said. “It’s relentless.”

He had to close for a few days, then things went back to normal. On a weekday afternoon last month, things felt pretty normal, too. A pleasant breeze rustled tree leaves as trucks rumbled toward nearby seafood processing plants.

Jimerson’s not too concerned about his own business, which sits on an upward slope. But he sees the flat expanse all around, and he worries about what’s coming.

“Everybody will be underwater to some degree,” he said. “Water, it’s heavy. You cannot stop it. And for anybody that lives down here or works down here, keeps building down here, who thinks that that’s going to change, you gotta be crazy.”

Credits

- Reporters: Catherine Carlock and Yoohyun Jung

- Editors: Tim Logan, Cristina Silva, and Francis Storrs

- Data editor: Yoohyun Jung

- Photographers: David L. Ryan

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Design, development, and graphics: John Hancock

- Interactives editor: Christina Prignano

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Audience: Dana Gerber and Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC