A playground in Hull was flooded in 2001.

Hull or high water: When climate change hits home

Town residents know flooding is a problem, but no one wants to leave.

Read more

- Water is coming for the Seaport; the whole city will be poorer for it.

- If Massachusetts can’t fix floody Morrissey Blvd., how will it keep all our roads and rails dry?

- Behind the levee: The forgotten communities at risk in Massachusetts

- Small towns, high tides: Across Mass., coastal communities grapple with rising seas.

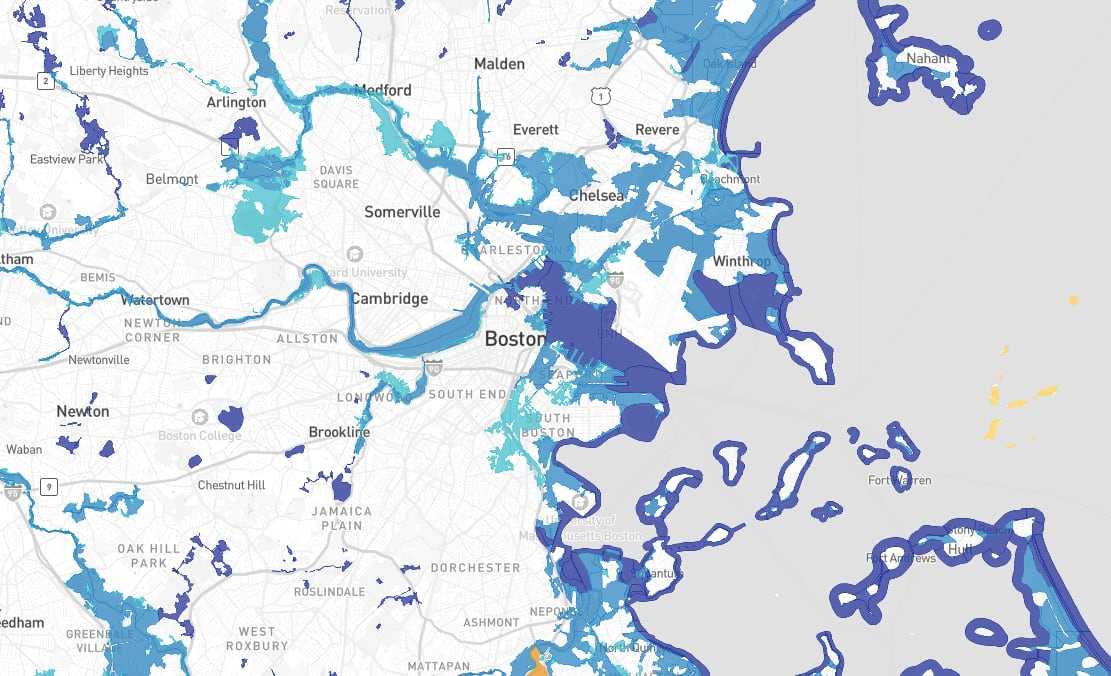

- Interactive map: Do you live in a flood zone?

Hull Massachusetts is a tiny beautiful beachfront community in a continuous battle against nature. The Massachusetts town sits on a low-lying, skinny peninsula prone to flooding from hide tides and storms. When it floods, homes can be damaged, residents may be cut off from the mainland, and emergency services can lose access to parts of the town.

Many residents agree this is a problem. But with climate change raising sea levels and increasing the likelihood of storms, Hull’s flood risk means residents are being forced to confront climate change, whether they believe in it or not.

In the latest episode for the Globe, four Hull residents share their experiences and perspectives on the changing nature of flooding.

Advertisement

Liz Kay: One of the things that drew me to this house in particular was being able to watch the sun move across the sky and set.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Liz Kay loves her view.

Liz Kay: And the light, the way the light moves through this house. Osprey will fly. We will have Canada geese move across. Those things are all really core to who I am.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Every day the sun paints an arc over Liz Kay’s picture window as her backyard endlessly welcomes the water. And every day Liz watches the forces that move that water.

Liz Kay: And that’s why I knew that my neighbor’s dock broke loose two nights ago and it floated on the 11 8 tide onto my property. Everybody deals with those issues differently for wherever they’re located.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Liz lives in Hull, Massachusetts, a town surrounded by water… and sometimes under it. The town of Hull is this unique, quirky, tiny spit of land about an hour long drive south from Boston, a seven mile peninsula in the shape of an upside down L. It juts into the capricious waters of the Boston Harbor. Roughly 11,000 people live in Hull. And the sandy Nantasket beach along Hull’s eastern ocean facing edge draws visitors from all over New England. And Hull residents are lucky to pass by the beach on the way home. But this magical town has a downside - a literal downside where parts of the town are lower in elevation than others, and during the storms and high tides, those areas flood.

Newsreel: Check out these waves in Hull Massachusetts.

Newsreel: This was from the latest high tide, and also causing some damage.

Newsreel: …that storm had the pressure and wind speed of like a hurricane.

Newsreel: Sometimes during high tide there isn’t much beach left and right now we’re at low tide and there’s not a whole lot of beach left.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Roughly ⅔ of Hull is in a coastal floodplain, so flooding is pretty much a fact of life in this community. And it has been for some time. But with climate change comes bigger and more intense storms. That, combined with rising sea levels and high tides, is forcing residents to confront it.

Chris Krahforst: I would say sea level rise is certainly a concern and it’s showing up as nuisance flooding elsewhere. That should be an indicator that our climate is changing

Bart Kelly: Climate’s always changed and it always will. If you live in a coastal community that’s in a flood zone, you’re vulnerable to coastal flooding.

Liz Kay: Hull is a long, narrow peninsula with lots of different neighborhoods So you actually find very different types of lived experiences environmentally.

Bryan Fenelon: The only two options you have if you don’t elevate is you try to get a bio from FEMA. But I just don’t know where I would go.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Today we have a story of a town in a continuous battle against flooding. One where residents and city hall employees all must reckon with the force beyond their control as they try to figure out how they will adapt to it. I’m Jazmin Aguilera, and this is The Globe.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): To live in Hull Massachusetts is to live through floods.

Bryan Fenelon: So far this winter, we’ve had one time where it’s egressed over the street. Before that, I believe I had a total of nine times in ‘24.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Bryan lives in Hampton Circle, A small neighborhood on Hull’s western side, the bay side.

Liz Kay: Brian lives up here and I live down here.

Bryan Fenelon: And this will probably help it a little bit more

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Around the corner and a few streets over is Liz Kay, who lives right on that shoreline. Liz and Bryan keep an eye on the tides and weather for possible flooding events.

Liz Kay: Brian there was an 11 8 tide last night, last two nights?

Bryan Fenelon: Yeah. I know

Liz Kay: The last -

Bryan Fenelon: …it peaked. It peaked at 12 2 because there was a tidal surge

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): In tidal terms 12 2 means 12.2 feet

Bryan Fenelon: I get affected when it reaches 13 2.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): When the tide is high, the backyards along Bay street can start to take on water.

Bryan Fenelon: This beach here at a 12.4 foot high tide the water will be up to the start of the asphalt and 12 5 to 12 6, it just starts to come over.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): And if there’s a storm surge or rain or heavy winds, any additional force that would push high tide waters or add to them, it floods.

[Sounds of water lapping a shoreline]

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Major floods in Hull are caused by a combination of high water levels and storms surges or torrential downpours.

[Sounds of rain and thunder]

The high tide saturates the ground and the rain drops excess water onto an already full drain system. This recipe, storms and high tides, is one of the conditions to pay attention to.

Advertisement

Bryan Fenelon: What will happen is that people that know, know that if it starts at a certain time, that this general area here where they are will move their vehicles. They have to move off the higher ground and then wait for the water to come in. And when the water goes out, they move their cars back. You have to walk around and say, Hey, listen, by the way, you should invest in either a tide chart or download an app because you have to watch out for these things.

Liz Kay: Because you, you can get lulled into believing that things are just really nice out here, but there’s a lot more going on.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host):Year-round residents like Brian and Liz have invested heavily in being prepared for the flooding.

Bryan Fenelon: Regular portable generators, the construction generators, that’s what I have. One of my…

Liz Kay: Wait, do you have, do you have like little 1400s, like little Hondas? I, you know, big ones?

Bryan Fenelon: No, I got two 8500s.

Liz Kay: Yeah. Okay.

Bryan Fenelon: It’s all a thing… is that you have to keep ahead of the water if you’ve got a basement and stuff like that.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Liz has a basement made of concrete block and her house has also been raised 4 ft.

Liz Kay: So I’ll take you into the basement of all of my appliances, everything is off the ground by four feet. I also have a sump and I can also put on a drive vac, and I also have a dehumidifier. But I have very little water that comes in, and so I deal with a very different experience than what Brian is dealing with.

Bryan Fenelon: So then naturally I’ve been here for 62 years. I’ve known over the years of what to do. When it’s predicting a 12 foot tide what I do, I go to, um, national weather service site for coastal projections to see what, like if we have a storm, what the rise will be. And if it’s telling me we’re gonna get a possibility of one and a half to two foot surge. I better start doing something because that means my cellar, my backyard, up to my front of my house is gonna be underwater. And people sometimes say I’m crazy because I’ll have sandbags pile up in my driveway and the pump’s running. When I’m all set with my pumps in my cellar, pumping away, then I’ll walk around the neighborhood and make sure the drains are open.

Bart Kelly: I lived in the area, gun rock area, my entire life on Atlantic Ave for 60 years.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Bart Kelly is the town’s building commissioner. He’s dealt with the floods his entire life too.

Bart Kelly: And I had my house for nine years and I lost three cars in nine years. Three different storms. Like I said, I lived down in Gun Rock. I bought my house in 1992 after the ‘91 storm.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): The Gun Rock neighborhood is one of Hull’s most southern neighborhoods. It’s surrounded by water, the Atlantic Ocean in front, and Straits pond behind, and it floods a lot. But that didn’t deter Bart…

Jazmin Aguilera: And you still kept living there for nine years?

Bart Kelly: Yeah, it…You get out when the storm’s coming.

Jazmin Aguilera: Yeah.

Bart Kelly: And I had to go get a, you know, to go get a bobcat and clean my driveway.

Jazmin Aguilera: Oh my God.

Bart Kelly: But it wasn’t a big deal.

Jazmin Aguilera: I mean, it’s a bobcat! I mean, I guess it’s not a big deal for you as a building person, but...

Bart Kelly: No, but I mean, me and my neighbors, we’d just split the cost.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): On the phone with me, Bart seemed kind of unfazed by the flooding issue, not like he didn’t care about it, he did, but more that he’d been dealing with it for so long that he just thought, well, it is what it is.

Bart Kelly: Like the blizzard of 78. The houses that got demolished in gun rock. They were a hundred years old. They were in an area that always flooded. So, uh, the best thing that you can do is to build to the resiliency standards and the building code and the, you know, the flood maps and make sure that you’re building to the proper code and the proper construction. Just like if you’re in an earthquake zone or you’re in a fire zone, or a heavy snow load zone, you gotta build to that code.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): And Hull has codes specific to flood compliance for most of the peninsula. Since 62% of Hull is in a 100 year flood plain, according to a Globe analysis of FEMA data, that means most of Hull is in the flood zone.

Bart Kelly: That’s why the town elevated the sea wall down there, ‘cause the town was constantly having to go down and clean the road after storms, you know, ‘cause of gravel and stuff washed across the road. That’s why they sent front end loaders down there, to clean it all up, push it back up against the sea wall and all that stuff. So they, you know, they got federal and state money to elevate the seawall by three feet. And that three foot and seawall elevation made all the difference in the world.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Sea walls are an important part of Hull’s infrastructure. They’re coastal defense structures, literally cement and stone walls made to deflect and disperse waves from eroding and flooding the land behind them. A few have existed here for generations already, and one is currently being rebuilt along Nantasket Avenue along Hull’s northern end. You can still see the remnants of the old sea wall there.

Kevin Mooney: The low wall, as we call it, that little wall that, so it was the worst condition. It collapsed and the wall needed to be moved.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Kevin Mooney is a civil engineer overseeing the project. It’s been in the works since 2014, and in fact, it was prioritized because of how crucial it was.

Kevin Mooney: One third of the town is past this point. If this wall went, one third of the town is cut off. There’s so much that goes on past this point: all the schools, coast guard station, ferry terminal.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): The $15 million project was funded by a combination of federal and state grants, and also by the taxpayers of Hull to the tune of $6 million. And it’s the first major sea wall in the state that has moved inward towards land, among other necessary fortifications.

Kevin Mooney: We are raising the road three feet. We are building up a vegetated barrier on the lagoon side, and we’re putting in a walkway. We had a lot of pushback from the townspeople because this road was a two-way road, and it’s now becoming one way. It’s a touchy issue for the people that use it. We’ve done the best we can to satisfy as many as we can. But overall, we’re looking for the protection of everybody. But we can’t do hard structures alone. We need to be able to integrate soft structures with it. If we still had beaches in front of our walls, we wouldn’t have all the issues we have with the hard structures. Bring back our beaches.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Beaches are a crucial part of Hull’s flood defense because they act as airbags that blunt the impact of storms and waves. So while seawalls deflect forces, beaches absorb them. And over on the eastern shore of Hull, along the stretch of Beach Avenue with no seawall protection, Chris Krahforst the town’s climate Director of adaptation and conservation was trying to protect the only natural defense that part of Hull has.

Chris Krahforst: I’m here to make sure that they’re not injuring the dunes and taking away or affecting the public’s interest in having those be protected.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): We met up with Chris on the sandy dunes off of W Street, where he was watching a crew that was cleaning up seaweed. As the crews on the beach scooped up the seaweed, Chris paid careful attention to the sand dunes underneath.

Chris Krahforst: This is the high area on the peninsula, at least in the flood plain. It’s the highest area, so if water gets through this area, it doesn’t just affect these homes, water migrates to the low areas, so all the homes behind have the potential to be flooded. So, we use the dunes as a very natural and inexpensive way to provide storm damage protection and flood control instead of building these big sea walls. Why not let nature help us? If they hit the dunes, they’re not hitting your house, so…

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): In fact, most of the peninsula of Hull was once a giant barrier beach. Barrier because it provided a barrier to the mainland protecting it from storms coming off the Atlantic ocean. And beach, because that’s exactly what Hull was, a big sandy marshy beach with dunes all the way across.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): But now that Hull has developed land with homes and buildings on it, the push and pull of the tides, the threat of storm surges and floods means Hull residents, like Bryan, have few options in the face of the flooding.

Bryan Fenelon: First off, elevation. Okay. This seems to be the, the new big thing. Let’s elevate the house. Okay. Awesome. So if you raise your house, put it up on stilts… now the real estate is selling you the water view. Say I have a water view, right? This house just went up. I don’t have my view anymore. Okay. So what’s gonna stop? Everybody starts raising the things now? And we have all these houses on stilts in the neighborhood? I mean, it really doesn’t look that great, you know? So am I happy? Not really.

Jazmin Aguilera: What’s the other option, if not elevation?

Bryan Fenelon: Well I, I guess the only two options you have if you don’t elevate is you try to get a bio from FEMA. And just leave.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): This option in climate adaptation terms is called planned retreat, and it’s a sticky topic for residents. No one I talked to wants to just up and leave. Back in the office for climate adaptation and conservation in Hull TownHall, Chris told me about the buyout program funded by FEMA, that the town coordinates on behalf of inquiring residents.

Chris Krahforst: FEMA offered a grant program that paid up to X amount of fair market value. Something like that. So there was that option too, and I’ve never actually engaged anyone on it.

Jazmin Aguilera: So no one’s taken the buyout yet?

Chris Krahforst: Well, not on their own, but they’ve expressed. I’ve had a couple of residents who said, “Hey, let’s, let me, let’s look at that a little bit more.”

Advertisement

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): For most people, retreat means leaving Hull entirely, although not for Chris.

Jazmin Aguilera: Aren’t you personally as a resident worried about flooding for your home or are you in the highland?

Chris Krahforst: I’m up on the highlands. Yeah. You know, out of the flood.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Turns out he’s done something of a retreat thing himself.

Chris Krahforst: I was in probably one of the worst spots, but I no longer am there. I used to be right on the beach.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): But making the decision to walk away from a big emotional and financial investment as buying a home almost always is, is not an easy thing to do, and that’s if you can find another home nearby.

Chris Krahforst: In our community, folks will say, well, Where am I retreating to? ‘cause we are a postage stamp, fully developed community. So for us to retreat means ‘See you later. I’m leaving the community.’

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Making the decision to move out of your home and hometown, that’s even harder. For Bryan, who has spent all 62 years of his life here, it’s almost impossible to imagine.

Bryan Fenelon: You’d probably have to move to another town, which doesn’t give you what you’ve strived for all your years, what you’ve worked for. And when you reach a certain age in your life and you try to re… reestablish yourself, I mean, I just don’t know where I would go.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host):All of these residents and local government employees agree that the town of Hull needs to respond to the flooding, but exactly how to respond and why dealing with the flooding is more urgent now than ever. Well, that’s a source of some contention.

Bryan Fenelon: Unfortunately, there’s too many committees.

Liz Kay: I am pretty convinced that that’s climate induced groundwater change.

Bart Kelly: The town misses opportunities because a NIMBY group says, oh, we don’t want that built there.

Chris Krahforst: Who am I answering to? And that’s the public. We’re actually managing climate change right now.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): That’s after the break.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): In Hull Town Hall, reminders of the ocean were all around us. In Chris’s office, the piles of Xerox paper smelled faintly of beachy mildew. And the file cabinets had a saltwater patina on them. On his computer Chris pulled up some graphs of sea level rise models.

Chris Krahforst: Let me see if I can show this to you quickly. And I did a little math exercise ‘cause that’s what I do sometimes. Um…[searching through files] conservation.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): The graph shows that flooding due only to sea level rise, as in the sea level rises so much that parts of Hull are permanently flooded by sea water, turning them into an island, is a danger could take decades to hit the community, maybe even less, it’s hard to say for sure.

Chris Krahforst: When would this curve hit 10?

Jazmin Aguilera: Oh.

Chris Krahforst: Year 2,150. But it could be, it could be instantaneous too. We could have glaciers severing off and falling into the ocean and getting a catastrophic foot rise too. So why not? I don’t know.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Right now Hull is like a pool deck, a bit of land that is meant to take on water. Hull has always been a flood-prone area that hasn’t changed. Hull has also had lots of big storms pass over through the years. That hasn’t changed. So the idea that climate change makes flood planning even more urgent than ever, for some, that’s harder to accept.

Bart Kelly: I’ve lived here my whole life. I don’t see that storms are more frequent. I see that it’s cyclical. It’s cyclical with the moon.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Bart Kelly doesn’t think climate change is responsible for flooding problems. He may not even fully buy into climate change at all.

Bart Kelly: I don’t think sea level rise is the cause. And it may or may not be happening. I don’t think that the dataset that they used at the UN climate study that they put out 20 years ago. And you know, Al Gore’s movie An Inconvenient Truth. Right? That movie, none of them came true.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): Gore’s movie, released in 2006, simply outlines the basics of what’s driving climate change, as well as the impacts of sea level rise. Gore wanted to alert people to the long-term predictions of what could happen to coastal communities if the world didn’t stop adding more greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere. Not guarantees, predictions. But predicting coastal flooding may not feel as scary in Hull, because Hull has always flooded.

Bart Kelly: And I can show historical photos of Hull, of Pemberton pier hundred years ago and Pemberton pier today. And you look like, you look at the rack line for the tide and it’s basically in the same spot. But I don’t know what day that picture was taken a hundred years ago. And I don’t know if it was a full moon tide. Right. So and then the dynamics of the beaches change all the time with storms and currents.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): But the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the NOAA which is the federal department in charge of all things oceanic affecting the country… like tides, sea levels, oceanic maps and so on… and they do confirm that sea levels have risen. The Boston harbor waters that Hull sits in has experienced at least a foot of it actually, from 1921 to 2023. That’s already happened! More than a foot of sea level rise in 100 years in the area.

Even the US Coast Guard now takes sea level rise into account in their war game training.

But, despite the data of rising sea levels in charts and oceanic maps, Bart’s perception of flooding and tides in Hull don’t match up with these warning signs. It just doesn’t look or feel right to him.

And what Bart thinks matters, he’s the building commissioner. And he clearly cares a lot about keeping his hometown vibrant and economically viable, but as someone who is skeptical about the effect of climate change on flooding…his approach to the flooding problem will have real influence on how Hull responds.

Across town and inside Liz’s home in front of the breathtaking views of the water from her picture window, we all crowded into her living room: Liz, Bryan, me and producer Anne Li, climate reporter Erin Douglas, and the elephant in the room. Climate change.

Reporter Erin Douglas: Do you think it’s gotten worse since you were a kid and growing up here?

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): As familiar as Bryan is with the flooding, he stops short of blaming the worsening floods to climate change. He never actually said the words climate change, though he does think flooding is getting worse.

Bryan Fenelon: It goes in spans. Usually every five to 10 years we’ll get our worst of it. Like 2018 we got hit bad. We only had a couple of floods that year. But we had the floods all together. ‘23, ‘24 it was like nine floods. But they was spread out over a couple of months. It goes by what the tides are right away ‘cause we have two actual high tides a month. Usually the second of the two tides is the higher of the two. But yeah, around of course it’s gonna get worse.

Jazmin Aguilera: Do you come together at the town hall and talk about it or is this just you guys being really ahead of the game here?

Bryan Fenelon: One thing is that, I don’t know if people want to know, you know, and if they want to listen. Around here, and a lot of times it’s when something does happen. Then people are like, ‘okay, I need to know something.’ We do have workshops sometimes.

Jazmin Aguilera: Is there disagreement?

Liz Kay: on what to do?

Jazmin Aguilera: Yeah.

Liz Kay: Sure.

Jazmin Aguilera: Yeah?

Liz Kay: Depending on where your property is located and what, how you would wanna experience it. Of course, there’s a disagreement, right?

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): And she would know. Liz is an active member on several committees and organizations, like Hull’s chapter of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council and a citizen action called ‘save our space’ Hull. These groups and committees often weigh in on community action or local government projects, and Liz emphasized to me many times how difficult it can be to square all of the different interests involved with any kind of community or local government project.

And that kind of disagreement, even if it can be a necessary part of the process, takes quite some time.

Bryan Fenelon: I’m gonna say this and it’s, I don’t know, people can take it the way they want.

Bryan Fenelon: Unfortunately, there’s too many committees. There’s too many commissions, there’s too many things that stuff have to go through. too much red tape, that everybody has to make sure that everything isn’t gonna hurt, this isn’t gonna do, this isn’t gonna, okay. Instead of just doing something, we have to wait for this group, this group, this group, this part of the state, this part of the government, for something to transpire. That’s all well and good, but the way these things happen, it takes at least 10 to 20 years. And who knows if they’ve designed something that was actually going to work.

Jazmin Aguilera (Host): If to live in Hull is to live through floods. And to grow up in Hull is to learn to deal with them. Then what does it mean to prepare for the future in a place like Hull?

Beyond looking to the past, as Bart Kelly does with his 100 year old photos.

Beyond looking to the present, as Bryan does with his generators and sandbags.

Beyond looking to the future as Liz has done with her committees and outreach.

Beyond looking to a possible future, as Chris Krahforst does with his models and predictors.

Everyone has to figure this problem out for themselves …and together. What does that look like when no one can start on the same page?

And yet, these neighbors with vastly different perspectives still try to work together.

CREDITS:

This episode was reported by me (Jazmin Aguilera), Erin Douglas, and Anne Li. Produced by Jazmin Aguilera and Anne Li. Sound designed and engineered by Jazmin Aguilera. Edited by Kristin Nelson and Jason Margolis. Special thanks to Ken Mahan, Yoohyun Jung, John Hancock, Christina Prignano, Tim Logan, Sabrina Shankman, Anica Butler, Cristy Silva, and Catherine Carlock

Listen to the podcast for in depth reporting on Youtube, Apple, Spotify, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts

Advertisement

Credits

- Reported by: Jazmin Aguilera, Erin Douglas and Anne Li

- Produced by: Jazmin Aguilera and Anne Li

- Sound design and engineering by: Jazmin Aguilera

- Editors: Kristin Nelson and Jason Margolis

- Design and development: John Hancock

- Audience: Dana Gerber and Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Thanks to: Ken Mahan, Yoohyun Jung, John Hancock, Christina Prignano, Tim Logan, Sabrina Shankman, Anica Butler, Cristy Silva, and Catherine Carlock

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC