A driver braved knee-deep water on Morrissey Boulevard, passing another vehicle that had gotten stuck in the water in June 2006. (Essdras M. Suarez/Globe staff)

If Massachusetts can’t fix floody Morrissey Blvd., how will it keep all our roads and rails dry?

The Dorchester parkway, one of Boston’s starkest examples of climate impacts, is inundated multiple times a year.

It was time for school, and the road to get there was underwater.

Ryan Murphy’s wife, Eva, called him from the car. She and their then-7-year-old son had been stuck on Morrissey Boulevard for over an hour, she said, during what’s typically a 10- or 15-minute commute to South Boston. There was nothing she could do but wait for the gridlocked traffic to crawl or the king tide to fall — whichever came first. By the time Murphy’s son got to school that morning in 2024, they had spent three hours maneuvering through the flooded roadway.

Read more

- Water is coming for the Seaport; the whole city will be poorer for it.

- Behind the levee: The forgotten communities at risk in Massachusetts

- Small towns, high tides: Across Mass., coastal communities grapple with rising seas.

- Hull or High Water: When climate change hits home

- Interactive map: Do you live in a flood zone?

Morrissey Boulevard is one of the starkest examples of Boston’s vulnerability to climate change. With sea level rise, the 100-year-old road along Malibu Beach near Savin Hill is no longer high enough to stay above water during king tides and increasingly unpredictable storms.

A Boston Globe analysis found that the boulevard has been partially or fully closed due to coastal flooding at least once every year since 2011. Increasingly, flooding hits several times a year. In 2024, for example, the road flooded at least four times — in January, February, September, and October, according to news reports and State Police announcements.

“It’s one of our most visible signs of regular flooding and what that might look like in the future,” said Courtney Humphries, a visiting assistant professor at Boston College who has researched Boston’s climate vulnerabilities. “It’s one of the most vulnerable areas of the city.”

It’s not just Morrissey Boulevard. In an old city that hugs the harbor, there are many critical roads, railways, and tunnels that were built decades ago for a climate that no longer exists. Yet as that sea inexorably rises, projects that would protect essential evacuation routes, train stations, and commuter thoroughfares from flooding have repeatedly failed amid community pushback, regulatory complexity, and the staggering cost of constructing a more waterproof city.

In 2024, Massachusetts highways were obstructed by flooding at least 14 times, according to Department of Transportation records obtained by the Globe. In July, the Southeast Expressway was inundated by flash flooding in Milton, stranding vehicles and closing traffic in both directions during the morning commute.

The MBTA system, too, which is used by well over half a million riders every day, has seen flood-related delays and closures. In May, service on a section of the Orange Line was suspended because of flooding on the tracks from a late-season nor’easter.

Tidal flooding and storm surge spilling onto critical roads like Morrissey Boulevard pose a huge safety risk: Transportation routes become impassable for ambulances and fire trucks racing to respond to emergencies, and residents are cut off from evacuation routes if they live behind the water line.

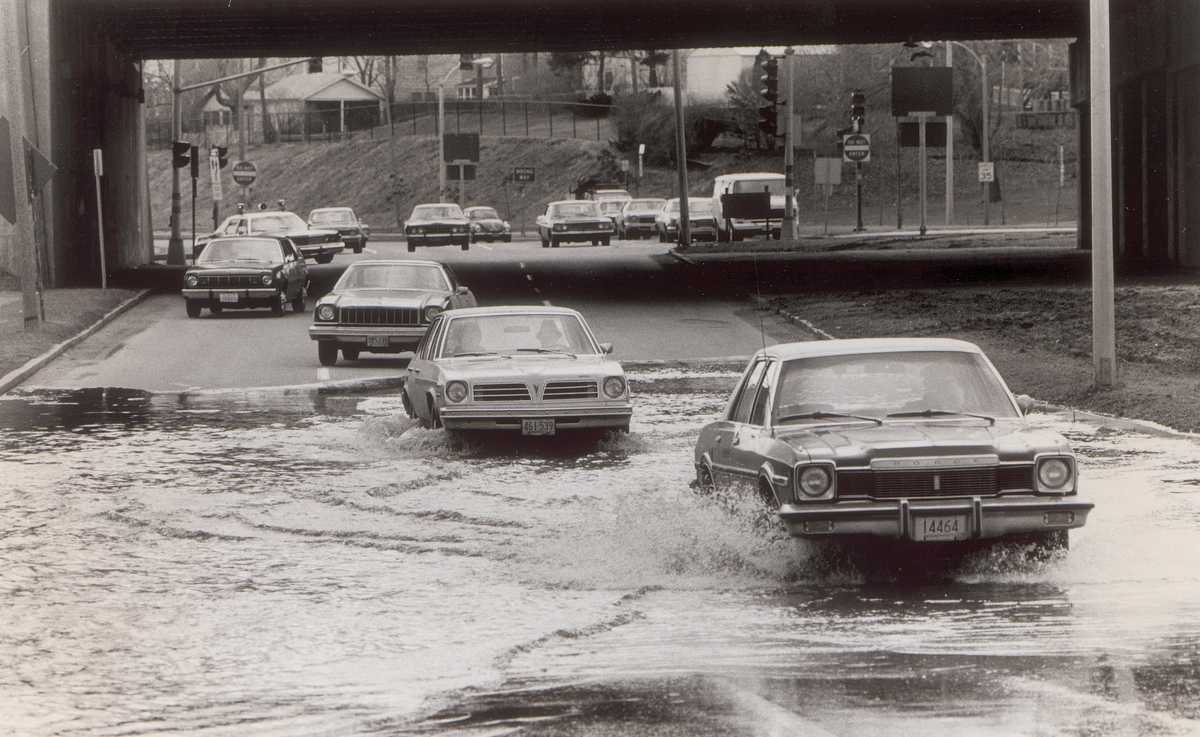

A flooded Morrissey Boulevard in 1984. (Tom Landers, Globe Staff)

Over the past three decades, local and state transportation officials have launched multiple efforts to both protect this relatively short stretch of roadway from flooding and to improve its nonsensical traffic patterns. But every time, the tangled multiagency effort has stalled, bogged down by disputes over details and a staggering price tag, most recently estimated at $300 million for just three miles of roadway.

Now, the city and the two state agencies that collectively oversee Morrissey are trying again, wrestling with how to either elevate the road or protect it from rising seas.

By 2050, some sections of Morrissey Boulevard could be under as much as 10 feet of water during severe storms, a Massachusetts Office of Costal Zone Management climate model shows. In downtown Boston, that same type of storm could bring 4 to 5 feet to the Aquarium T stop entrance. And a three-mile stretch of North Shore Drive between Revere and Lynn could be under as much as 10 feet of water.

Every closure comes with costs of its own: time lost for commuters, businesses cut off from their customers, and tourist trips not taken. A recent climate risk assessment by the state Department of Conservation and Recreation found 60 miles of parkways in the Boston metro region will be at risk of flooding by 2030. Road closures from those floods could cost $25 million per day, mostly in lost business revenue.

When floods cut off access to whole neighborhoods

Morrissey Boulevard serves not only as a critical throughway for residents and commerce — it's a vital evacuation route. Whole neighborhoods including Dorchester's Columbia Point are at risk of isolation when roads like Morrissey Boulevard are inundated.

Flood vulnerability level

- Low

- Medium

- High

- Very high

- Isolated community

By 2070, the assessment estimates that up to 92 miles could be at risk, including roads that serve as vital evacuation routes. If those roadways are inundated, it would isolate whole neighborhoods in Boston, Quincy, Hull, and other waterfront communities.

The water in Boston Harbor has already risen by about a foot over the past century, and climate scientists expect that pace to quicken. A model of Massachusetts’ climate risk suggests the seas here will likely climb by a few more feet over the coming decades, causing low-lying roads, rail lines, and tunnel entrances to easily flood at high tide and during storms.

The time to act, climate change experts warn, is now, before the water climbs even higher.

“The 2030s are going to be a tough time for Boston,” Humphries said. “This is the time to get something done.”

Advertisement

Just above high tide

Morrissey Boulevard opened in 1924 as Old Colony Parkway, a new seaside route for motorists to take from southern Dorchester up to South Boston and downtown. Like many other coastal parts of the city, the parkway was built in part on artificial land, or fill.

Roughly one-sixth of Boston, and parts of Cambridge, is artificial land — likely a higher share than any other major US city. Because it’s expensive and labor-intensive to dry out and fill tidal flats with timber, dirt, and rock, the “made” land, as researchers sometimes call it, was typically only built just above the high tide mark of that era.

By the 1990s, it was clear that Morrissey was far too low to withstand more frequent coastal flooding. In 1997, state lawmakers sought to elevate the road and lobbied the Metropolitan District Commission to create an improvement plan.

Without funding, the plan went nowhere.

A man walked down a flooded Morrissey Boulevard during the Blizzard of '78. (Janet Knott/Globe Staff)

By the 2010s, closures on the boulevard were as routine as the tidal calendar and became one of the region’s clearest examples of “sunny day” flooding — days when tidal flooding occurred even without heavy rain or storm surge.

In 2014, Owen Thomas and his wife moved into a small, gray fixer-upper in Savin Hill, their first home.

“We didn’t really know anything about Savin Hill before we moved there,” Thomas said. “Once we began talking to neighbors, very quickly we were told about the flooding.”

In 2015, the Department of Conservation and Recreation kicked off a new effort to protect Morrissey. They planned to either elevate the road, build a berm, or construct a sea wall.

The agency spent a little over $3 million to hire engineers, landscape architects, and ecological specialists. It collected traffic, environmental, and topographic data. There were public meetings and conceptual designs that included not just an elevated roadway but plans to improve traffic flow and better accommodate walkers and cyclists.

The idea to add more more bike lanes and pedestrian improvements along Morrissey proved to be a political hurdle — especially among commuters who drove it daily. Some residents and community leaders said the carbon-conscious vision ultimately sunk the project.

The effort died on the watch of then-mayor Martin J. Walsh. In an interview, Walsh said he was a big advocate for the project during his seven years in office, but didn’t want to trade car lanes for bike lanes. Plus, he said, the price tag was too big for state lawmakers to swallow.

“It was the cost,” Walsh said. “It’s not a simple project.”

Advertisement

Transportation systems at risk

Beyond Morrissey Boulevard, bracing Massachusetts’ transportation infrastructure for flooding will require an enormous amount of money and effort. There are bridges to strengthen, culverts to widen, sea walls to construct, and berms to build.

Flood protections alone for the Central Artery tunnels, which include several watertight flood gates to prevent water from entering them, will cost $243 million, according to estimates from a 2015 study.

Without mitigation measures, coastal flood damage could cost the MBTA system $39 million annually by 2030, according to Lynsey Heffernan, the MBTA’s chief of policy and strategic planning. Some efforts have been undertaken. After the Blue Line Aquarium Station on Long Wharf sustained $3.5 million in damage during a 2018 nor’easter, the MBTA made flood-proofing upgrades at the station, at a cost of $1.7 million, including a deployable metal flood barrier.

Flood barriers protected the entrance to the Aquarium Station on the MBTA's Blue Line ahead of a nor'easter in October. (Danielle Parhizkaran/Globe Staff)

Yet, even relatively small flood protections tend to cost millions of dollars, the state’s most recent transportation capital plan shows. For example, replacing a culvert to prevent clogging and roadway flooding during heavy rainstorms on Route 6A in Barnstable is estimated at a little over $1 million; another culvert project in Oaks Bluff on Beach Road will cost $6 million; and upgrading a drainage system to stop flooding on Route 20 in Worcester will cost more than $7 million.

That’s just three projects. There are more than 25,000 culverts and small bridges in Massachusetts, thousands of which are inadequate to keep up with more intense rainfall and more frequent coastal flooding.

The full cost to protect the Commonwealth’s transportation infrastructure won’t even be known for years. The state’s transportation agency is in the midst of a flood risk assessment for highways, roads, bridges, large culverts, rail lines, and public-use airports. They expect to complete it in 2031.

Meanwhile, the risk keeps growing.

On Cape Cod, for example, dozens of low-lying roads are already flooding, a 2024 analysis by the Cape Cod Commission found. Big swaths of important roadways are expected to flood frequently by 2050, including parts of Route 6 and 6A in Provincetown and in Orleans.

Sea level rise projections vary in severity depending on actions to reduce fossil fuel consumption, but climate scientists said it’s clear that flooding is only getting worse in New England.

Warming oceans are melting glaciers and expanding the water itself. The seas are rising in few places faster than they are off the northeastern United States, making Boston one of the most vulnerable major cities in the country.

Storm clouds over the Back Bay in June 2024. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

At the same time, heavy rainfall — also more common as the climate warms — compounds the problem. Since 1958, the Northeast has seen a 60 percent increase in the average number of days per year with at least three inches of rain. Extreme rainfall can devastate roads and homes, like in Vermont this summer, and can be deadly, like in the Texas Hill Country earlier this year, when heavy rain caused the Guadalupe River to overflow its banks, killing more than 100 people.

Third time’s the charm?

During a storm in 2022, Morrissey Boulevard was flooded, and traffic was halted. Thomas was at home in Savin Hill.

For years, he’d complained that the road blocked access to the water. Now, the water had come to him. He had an idea.

He grabbed his boat and paddle and asked a neighbor to follow him with a camera as he attempted to be the first person to kayak the highway.

“It was just kind of a joke to get a first descent of Morrissey Boulevard,” Thomas said.

Thomas’s stunt drew spectators and local media coverage.

“I realized people were paying attention,” he recalled. ”It felt like a good opportunity to highlight the fact that there could be more being done for climate resiliency.”

When Morrissey Boulevard flooded in 2022, Owen Thomas took out his kayak. (Eva and Ryan Murphy)

Climate change was by then becoming a larger political issue for Bostonians, with Morrissey Boulevard as one of its most poignant symbols. When she was running for mayor in 2020, then-City Councilor Michelle Wu went to Morrissey Boulevard during a king tide to highlight her plans for a “green new deal” for Boston.

“[We’re here] to mark what will be an increasingly frequent sight in our city,” Wu said during the press conference that fall. “The regular flooding on a beautiful sunny day from sea levels going up and up.”

In 2023, with Wu as mayor, a third effort to redesign Morrissey Boulevard began, led by a coalition of state and local transportation authorities called the Morrissey Commission. Soon enough, residents and civic groups were again debating cars versus bikes, as well as the impact of new traffic from large apartment buildings that had sprung up in Dorchester.

Then there was the sea wall.

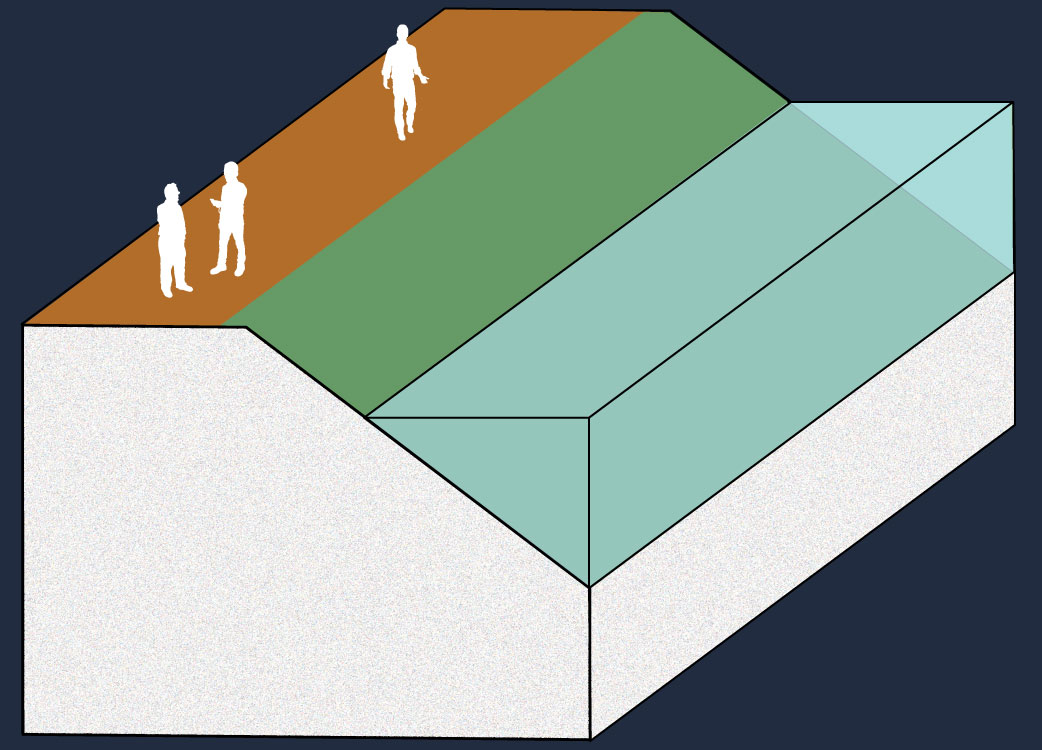

Natural elevation changes to reduce the impacts of coastal flooding. (Source: Morrissey Boulevard Corridor Study Draft Report. People illustrations by ProPublica/Wee People. JOHN HANCOCK/GLOBE STAFF)

In the spring, planners published a report contemplating several options, from raising the road several feet to adding a sea wall. The options entailed fewer car lanes, new bike lanes, pedestrian infrastructure, and some sort of berm that could serve both as flood protection and a waterfront park.

Frank Baker, a former Dorchester city councilor who recently announced he’s running for an at-large seat, said he’s heard that the berm is quickly becoming a new political sticking point among Savin Hill residents. The Morrissey Commission’s report noted that a berm, flood wall, or road elevation — depending on what is eventually built — may need to be as high as seven feet. In a neighborhood where water views are a big part of the appeal, no one wants theirs blocked.

“A high sea wall is a nonstarter for us,” longtime resident and Columbia-Savin Hill Civic Association president Bill Walczak said. (He said he would prefer a harbor-wide barrier over localized flood infrastructure.)

Then there’s the money. The central section of the project alone — which contains most of the flood resilience measures — will cost around $141 million. Separately, the crumbling Beades Bridge, which carries Morrissey over Dorchester Bay Basin, needs to be replaced at a cost of more than $100 million. On the north end of the Morrissey Boulevard, redesigning Kosciuszko Circle, a nightmarish rotary that’s long frustrated residents, is expected to cost $92 million.

With the Trump administration pulling back on federal funds, particularly projects for climate resilience, Walczak wondered: “Where are they going to come up with the money?”

The report outlining potential designs is just the beginning of a long process of design, permitting, financing, and construction. Even if all goes according to plan, groundbreaking is likely a decade off.

Chris Osgood, Wu’s director of the Office of Climate Resilience, said in a statement that Morrissey is a high priority for the city, which contributed $500,000 to help fund conceptual design.

“We have never been closer to getting a shovel in the ground,” Osgood said.

Advertisement

Morrissey today — and tomorrow

Osgood’s optimism is not necessarily shared by Savin Hill residents.

Last fall, the neighborhood civic association took a vote of no confidence in the Morrissey Boulevard Commission. And other Savin Hill residents told the Globe they doubt the Morrissey project will ever come to fruition.

The problem, they said, has been passed from one mayoral administration to the next, and they’re frustrated by being asked for community input only to see their ideas left to die in forgotten PDFs and out-of-date renderings.

Many who want to stay in the neighborhood are learning how to live next to a road that is increasingly underwater.

A warning to motorists along Morrissey Boulevard in 2018. (David L. Ryan)

Murphy, the dad whose son’s school commute can be interrupted by flooding, said that these days, if high tide is expected to be near 12 feet, his family runs their errands at low tide or makes a plan to leave their car at home and get around on the T.

“We know not to bother trying to get in the car on those days,” Murphy said.

The redesign effort is a “pipe dream,” he said.

“No one can agree on a solution.”

His hope for this Morrissey Commission’s effort?

“In some ways, I wish they wouldn’t listen to anyone,” he said. Stop with the drawn-out public input that never seems to go anywhere, he said, “and just make it so that it doesn’t flood anymore.”

Credits

- Reporters: Erin Douglas

- Editors: Tim Logan, Jason Margolis, Cristina Silva, and Francis Storrs

- Data editor: Yoohyun Jung

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video producer: Jackline Luna

- Director of video: Anush Elbakyan

- Design, development, and graphics: John Hancock

- Interactives editor: Christina Prignano

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Audience: Dana Gerber and Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC