Catherine Gonzalez with her son, Kyrie Cortez, 8, and daughter, Paula Cortez,16, stood atop the levee that is a few houses away from her home in the Willimansett neighborhood of Chicopee. (Barry Chin/Globe Staff)

Behind the levee: The forgotten communities at risk in Massachusetts

People living behind inland levees are facing a climate-fueled risk that is often overlooked, but which could soon bring disaster.

CHICOPEE — Catherine Gonzalez knows the water always wins.

She remembers being 5, riding on her father’s shoulders as he trudged through chest-high water to escape to higher ground in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico. As Hurricane Hortense barreled through in September 1996, the river overflowed its banks, taking her home and belongings, but thankfully not her family. Others weren’t as fortunate. After 20 inches of rain, flash flooding, and mudslides, at least 18 people were dead.

In the wake of the devastation, Gonzalez and her family followed relatives to Chicopee, a town defined by its relationship to two rivers — the Chicopee and the Connecticut. A place less prone to hurricanes. A place that was supposed to be safe. But Gonzalez worries it brings dangers of its own.

Read more

- Water is coming for the Seaport; the whole city will be poorer for it.

- If Massachusetts can’t fix floody Morrissey Blvd., how will it keep all our roads and rails dry?

- Small towns, high tides: Across Mass., coastal communities grapple with rising seas.

- Hull or High Water: When climate change hits home

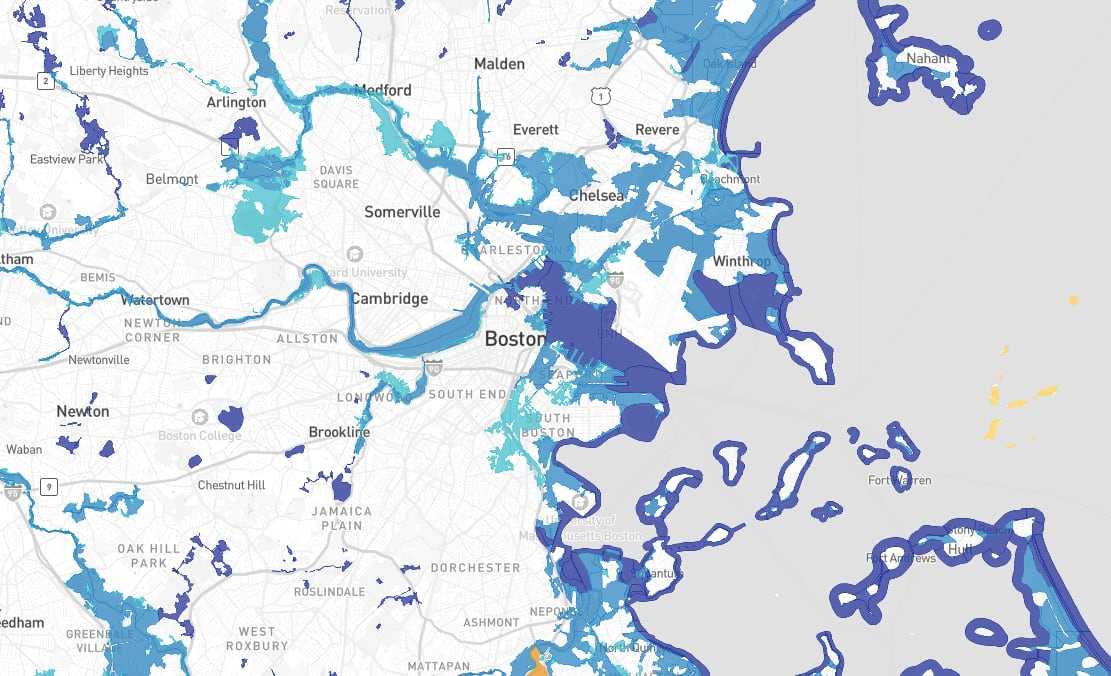

- Interactive map: Do you live in a flood zone?

Gonzalez, who is 34, lives in the Willimansett neighborhood, six houses up from a levee along the Connecticut River. The levee is meant to protect her and roughly 9,000 of her neighbors, she knows, but she fears the river will one day spill over, swallowing whatever stands in its way.

“It’s a little scary that it’s there, to be honest with you,” said Gonzalez, who, like many others in Massachusetts, ended up living near the levee after being priced out of other areas.

Should the levee near Gonzalez’s home fail, a 26-foot deluge could inundate the tight-knit neighborhood of single- and multi-family homes, warns the the US Army Corps of Engineers. People could die, the Corps warns, and more than $450 million in damages could occur in this area.

An Army Corps report indicates the levee should be able to withstand water rising to the top without breaching, but points out that it’s never really been tested beyond 50 percent of its height. “It is important to note that breach is possible,” the report warns.

Far from the rising seas that threaten the coast, people living behind inland levees are facing a climate-fueled risk that is often overlooked but which could soon bring disaster to their doorstep.

Gonzalez and her family are among the 330,000 people in Massachusetts living in the shadow of levees — built decades ago and often relying on World War II-era pump stations to move water from the neighborhoods to the river. These levees, sometimes 20 or 30 feet high, are there to hold the river back and protect the people and businesses built up along the water’s edge. But the climate has changed, and so, too, has the risk of living beside the water.

A view of the levee near the Paderewski Street Flood Control building in Chicopee. Massachusetts' levee system was built for a different time with more predictable rainfall and fewer extreme events. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

The Depot Street Flood Control area in Chicopee. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

With increased precipitation and more extreme events that dump several inches of water at once, the risk is now twofold. First, the river could overtop the levee or cause it to fail, pouring into adjacent streets. Second, extreme rainfall could cause a flood along the side of the levee, with aging pump stations unable to quickly move the water from the roads into the river.

Nationwide, 23 million Americans live and work behind levees, which protect $2 trillion worth of property. But the levees are aging. Earlier this year, the American Society of Civil Engineers issued its annual infrastructure report card: The nation’s levee system got a D+.

In Massachusetts, levees protect nearly $10 billion worth of property, according to a Globe analysis, and yet town managers and operators of levees have said they are largely without the needed funds to upgrade, replace, or repair their aging systems. What’s more, recent research indicates that Massachusetts, more so than most states in the nation, has a major disparity in who is most likely to live behind levees. Here, those people are most likely to be Hispanic, in poverty, disabled, uninsured, lacking access to a vehicle, and without high educational attainment.

“Massachusetts has a lot fewer levees than some other places, but those that we do have are in far more inequitable locations,” said Farshid Vahedifard, an engineering researcher with Tufts University who has studied the demographics of those living near levees.

Disasters are rare, but catastrophic when they occur. And they’re already happening elsewhere in the United States.

Two kayakers tried to beat the current pushing them down an overflowing Brays Bayou in Houston in August 2017. (Mark Mulligan/Houston Chronicle via AP)

Levees along the Black River in Arkansas and Missouri have failed or been overtopped repeatedly over the years — most recently in April — forcing mass evacuations and necessitating rescues. Pump stations in Texas were overwhelmed by the massive rains of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, contributing to catastrophic flooding there that killed 89 people and caused the widespread loss of homes and businesses. And when levees in New Orleans failed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, 80 percent of the city was submerged, killing roughly 600 people.

“We’ve always referred to levees as a two-edged sword,” said Nicholas Pinter, a geologist and the associate director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California, Davis. “They do protect people and infrastructure — until they don’t."

Advertisement

The trouble with pumps

If something goes wrong with Chicopee’s levee, Chris Owsiak — a goateed, motorcycle-driving Phish-head — is the guy you call. And if nothing goes wrong, which is most often the case, it’s likely thanks to Owsiak, too.

A longtime Chicopee public works employee, Owsiak is now the city’s flood control supervisor. He tracks incoming rain storms, watches for increased river flow, and makes sure the levees and pump stations are maintained at all times.

They have to be maintained just-so, because, in addition to keeping people safe, as long the levees meet the Army Corps of Engineers’ requirements, the people living behind them are not required to buy flood insurance, which can cost $1,142 on average for a single-family home in a flood zone.

Chicopee is one of many Connecticut River communities with aging levee systems, including Holyoke, Springfield, and West Springfield. They are in other places, too, such as North Adams, Lowell, and Haverhill. In each place, there are people like Owsiak — people whose job it is to work behind the scenes — averting catastrophes that most people never even knew were possible.

On a recent day, Owsiak’s massive keyring rattled as he pried open the doors of one of eight pump stations he maintains and operates along the levee system in Chicopee — five stations on the Connecticut River and three on the Chicopee.

By 2050, flood risk is expected to nearly double in Chicopee

Both the streamflow and heavier rainfall would contribute to heightened flood risk, a climate research firm's analysis shows.

- Flood/stream overflow (2050)

- Levees

- Pump stations

He entered one known as the Broadcast Center Flood Control Pump Station — formerly called Bertha, for the avenue that was here before the highway came in. Similar to many other pump stations, it’s a tidy box of a building with its construction date — 1940 — displayed on a sign near the entrance.

Walking down echoing stairs, he revealed curving blue pipes, each like a giant snail shell plugged into either side of the building’s lower level.

“These pumps are original — 1940," he said, looking around. “Well, everything down here is original.”

Chris Owsiak, Chicopee's flood control supervisor, looked over pumps installed in 1940 at the Broadcast Center Flood Control building in Chicopee. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

Five of the city’s eight pump stations have gotten electrical and plumbing upgrades at some point, and in the late 1980s and ’90s the diesel motors were updated. But pumps are tricky.

“Our biggest problem is that some of these pumps, the companies that make them have been out of business since like the ’70s and ’80s,” he said. “So where do you get parts?”

Sometimes he turns to local vocational schools for help fabricating replacement parts. Other times he just figures it out, leaning on what his predecessors taught him.

No matter how effective and vigilant Owsiak is, pump stations like these are “generally one of the more vulnerable parts of a levee,” said Douglas Garman, a spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers. Most in Massachusetts and elsewhere are beyond their estimated 50-year design life, he said, though with proper operation, maintenance, and testing, they can often perform longer.

Adding to the challenge is that many parts of the city still use aging water pipes that combine storm water runoff and sewage. When there’s a storm, the system diverts the untreated overflow to pumps that can send it into the rivers.

And there’s nothing automatic about it.

It’s a massive volume of water to oversee. Add extreme weather to the mix, and the will of nature could surpass what Owsiak and his peers up and down the Connecticut River and along levees in Massachusetts can do on their own.

In nearby Holyoke, former interim public works director Mary Monahan has faith in her city’s levees — especially after the state provided a $777,000 emergency grant this year to repair damage to them. But that doesn’t mean the risk is gone.

“The waters will come,” she said. “The challenge with climate change is to make sure that the recovery is addressed ... because you can’t design your way out of that great big flood.”

Or, as West Springfield’s director of public works Trevor Wood put it: “Every time it rains, I don’t sleep a lot.”

Advertisement

It’s a different climate today

The levees in Chicopee were built to withstand a 100-year storm — the kind of event that, in this area, amounts to 8 inches of rain.

Now a storm that size can be expected every 42 years, according to analysis by First Street, a nonprofit that develops property-level climate risk data.

Every increment of global warming means the atmosphere can hold more moisture — about 7 percent more for every degree Celsius of warming.

The planet has already heated up by roughly 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.3 degrees Fahrenheit) since pre-industrial times, and it’s poised for a lot more. A 2023 report from the United Nations Environment Programme found that, if the world’s nations made good on their existing climate pledges, Earth would see roughly 2.9 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of this century — and that was before President Trump canceled the nation’s climate commitments and doubled down on fossil fuels.

The Northeast is especially vulnerable. The region has already seen a 60 percent increase in annual precipitation from major storm events since 1958 — the largest increase anywhere in the United States.

All that is to say: A lot more warming — and a lot more moisture and precipitation — is in store.

Last year, Chicopee’s planning director, Lee Pouliot, reached out to The Woodwell Climate Research Center and asked them to work up a climate risk assessment for the city.

The results affirmed what Pouliot was worried about: Chicopee’s residents are facing significant flood risks, beyond what the Federal Emergency Management Agency has predicted.

The Woodwell report found that FEMA’s flooding projections left out huge portions of at-risk properties because the agency only takes into account flooding from the river — not from rain storms. FEMA also relied on data that is several decades old (the Connecticut River analysis was conducted in 2006; the Chicopee River analysis was done in 1978).

The high water gauge at the Depot Street Flood Control area in Chicopee. (David L Ryan/ Globe Staff)

A lot of levees weren’t designed to consider “pluvial flooding” — flooding caused by rainfall — said Dominick Dusseau, a research associate at Woodwell, where he analyzes climate models to help decision makers better understand risk. When data on pluvial flooding is factored in, Dusseau said, it’s clear: “Pump stations are generally quite underprepared.”

One of the challenges, he said, is that people are largely unaware they’re facing any risk at all.

“The government says, ‘This levy is certified for the 100-year or 500-year event.’ Why would you question it, right?” Dusseau said. “But in many cases ... dams have failed, levees have failed. So it’s not a matter of if, but generally when, unfortunately.”

Advertisement

So, who pays?

City leaders and public works officials along the Connecticut River can point to any number of upgrades that need to happen to mitigate the risk.

Electrical upgrades, pump replacements, levee repairs, sewage system upgrades. Where do you start? And how do you pay for it?

And in the face of a catastrophic failure or rush of water, would any amount of planning and money be enough?

Pouliot, of Chicopee, has been wrestling with that. There’s no solid number for what all of the levee-related upgrades might cost, but he said it’s likely in the “many hundreds of millions” of dollars.

The trouble is, there are also so many other needs in this city of 55,000 people where the income level is two-thirds the state average — better schools, roads, sidewalks.

“They’re all a priority. It’s really difficult to say that one outranks the other,” he said.

What’s more, there’s no clear place to ask for help, especially given the Trump administration’s rollback of the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act, which had made available billions of dollars for resilience-related infrastructure upgrades.

Earlier this year, Governor Maura Healey proposed legislation that offered some hope. Her Mass Ready Act — a sprawling, $3 billion bond bill — includes the proposed creation of a Connecticut River Valley Resilience Commission to bring communities together to develop a regional strategy for addressing flood risks along the river.

“Step one is really just understanding the needs, prioritizing them, and coming up with the roadmap,” Katherine Antos, state undersecretary of decarbonization and resilience, said in an interview when the act was announced in July.

It’s welcome news to Patty Gambarini, chief environmental planner at the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission. She and her colleagues in the planning world have been wrestling with where to even start tackling the problems facing Connecticut River communities.

“There are just so many projects that could be done,” she said.

“How we pay for critical projects in these times is perhaps our greatest challenge,” she added.

Bracing for the worst

Sitting on her back porch on a late-summer afternoon, Catherine Gonzalez grabbed her cellphone and checked the time. She was in between her two jobs — finished for the day as a property manager and headed soon to her shift as a home health aide.

Catherine Gonzalez worries about the risk of living near the levee. (Barry Chin/Globe Staff)

Her kids, ages 16, 13, and 8, occasionally popped out of the screen door, asking about snacks and plans for the afternoon — the typical thrum of a busy family.

The thing about Chicopee, Gonzalez said, is that she loves it here. Her husband, who owns a barbershop nearby, is her high school sweetheart. Her kids have good friends and strong ties to the school.

She just wishes she could shake the fear that living so close to the water means tempting danger — means risking repeating the trauma that forced her family to leave Puerto Rico.

“When there’s tropical storms going on, or hurricanes in other places,” she said, her thoughts turn to the river beyond the levee, just six houses away. “I think storms are happening more now than they ever did. So we should expect the worst, right?”

Credits

- Reporters: Sabrina Shankman

- Editors: Jason Margolis, Cristina Silva, and Francis Storrs

- Data editor: Yoohyun Jung

- Photographers: Barry Chin and David L. Ryan

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video producer: Jackline Luna

- Director of video: Anush Elbakyan

- Design, development, and graphics: John Hancock

- Interactives editor: Christina Prignano

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Audience: Dana Gerber and Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC