Dr. Jamie Adler and her newborn, Coco, in their Needham home. SUZANNE KREITER/GLOBE STAFF

Parking lot drug exchanges. A $300,000 baby. In Massachusetts, fertility coverage shortfalls cost patients dearly.

Massachusetts is known as the promised land for fertility coverage. So why are so many women left out?

It was midday when the nurse pulled her car into the Market Basket parking lot in Hanover and sidled up to a black SUV.

She said hello to the SUV driver, a suburban mom she’d connected with in a private Facebook group. The driver got out and handed the nurse a plastic bag. Inside, nestled in ice, were drugs worth thousands of dollars.

“Good luck,” the woman said, then vanished into the grocery store to buy food for her family.

The nurse sighed with relief — she had enough hormone shots for today. But tomorrow, she’d have to drive to Waltham to pick up another shot from another stranger, this one a licensed pharmacist.

Even though no money changed hands, she knew the whole thing might look sketchy.

But when you’re struggling to have a baby in Massachusetts these days, you do whatever it takes.

An embryologist worked in the IVF lab at the Brigham & Women's Hospital in Boston in 2024. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

The nurse hadn’t expected in vitro fertilization to work this way. She had been trying to get pregnant with her husband for well over a year, but her husband didn’t have insurance coverage for IVF or any assisted reproductive technology through his job. She did, through her employer, South Shore Hospital, but her specialty drug benefit maxed out at $15,000. With her first box of medication, she had already exceeded the limit.

Soon, her fertility clinic called to say she might need more of one drug — at a cost of $2,500. In desperation, she turned to Facebook.

“It’s very stressful,” said the nurse, who spoke on condition of anonymity because exchanging prescription drugs is illegal. “Do I order it? And bite the bullet? Or spend my day off traveling here, there, everywhere hoping someone has this med?”

Massachusetts has long been seen as a promised land for people struggling with infertility, and in many ways it is. In 1987, the state became the second in the nation to require insurers to cover fertility treatments, including IVF, which can cost between $15,000 and $25,000 per cycle without insurance. Today, it’s still one of only 16 states requiring insurance companies to pay for IVF.

The Massachusetts mandate has helped tens of thousands of people have children. But for an untold number of others, it has not been nearly enough.

The law only applies to a subset of the market — people with commercial insurance purchased individually or by their employers. Most glaringly, it does not cover individuals on MassHealth, the state’s Medicaid program, which insures approximately 2 million people. That gap in the mandate blocks access to fertility services for poor and working-class people as well as thousands of individuals with disabilities and has a disproportionate impact on certain minority groups. A Globe analysis found that after adjusting for population, a Massachusetts baby born after IVF was 2.6 times more likely to be white or Asian than Black or Hispanic.

Other groups are left out, too. Active or retired members of the military have some coverage for IVF, though most other federal employees finally gained it this year.

Coverage is also not mandated at “self-insured” companies, where employers pay health care claims directly. While most employers elect to voluntarily provide such benefits, a growing portion do not.

Add up all of those carveouts and this state doesn’t look like such a promised land after all: more than 1 in 4 Massachusetts women of reproductive age — a group numbering in the hundreds of thousands — don’t have fertility coverage. That’s according to a Globe analysis of records from the Division of Insurance and a 2022 study of the then most recent available data, compiled by researchers from the University of Connecticut and Harvard, Tufts, and Brown universities.

“Our goal would be 100 percent access for all patients who are in need of fertility care,” said Dr. Katherine G. Koniares, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist who co-authored the study of the 2019 data. “There has been an increase in the number of states with mandates. We are making progress, but we still have a long way to go.”

US Senator Tammy Duckworth, an Illinois Democrat and a recipient of IVF treatment, held a photo of her family as she joined fellow Democrats at a press conference outside Capital Hill last year on paying for IVF treatment. (Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

How many would-be parents want children and don’t have a chance to conceive them because of barriers to access? In Massachusetts, around 4,000 mothers give birth after fertility treatments in a typical year. That suggests that if all residents had equal access to such treatments, roughly 1,300 more mothers would give birth each year.

The hurdles persist despite angst at the national level over a declining American birthrate and repeated promises to improve access from President Trump. In February, he signed an executive order to make fertility treatments cheaper and more available, and last week he announced that one fertility drugmaker had agreed to cut costs on expensive IVF medications.

Even Massachusetts residents with fertility benefits can find themselves at the mercy of exceptions, limitations, and a dizzying array of hurdles. Entire swaths of care are neither covered by typical insurance nor addressed in the Massachusetts law — such as universal coverage for donor sperm or eggs. Some plans offered by self-insured companies have spending caps or don’t cover fertility drugs at all.

A view of a cryo solution during embryo prep seen with a microscope at an IVF lab at the Brigham & Women's Hospital in Boston in 2024. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

Treatments are particularly expensive for LGBTQ+ couples and single parents. The law defines infertility as an inability to conceive after 6 to 12 months of trying. This means lesbian couples and women who are single by choice often must pay additional costs to prove their infertility before they can access some treatments.

The Globe has spoken to more than 60 people over two years who have sought treatment for infertility. The vast majority encountered challenges navigating insurance and treatment, and affording some of the costs — burdens that come on top of high emotional and physical demands.

The holes in the system leave people struggling to find any pathway to parenthood. Some juggle multiple jobs to access benefits. Some buy drugs from overseas, or take risks to connect with internet acquaintances here, striking deals for everything from unused meds to embryos. Others rack up tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in bills, draining retirement accounts and trying to pay off credit cards for years — sometimes without a child to show for it.

“Building a family for many people is existential,” said Dr. Neel T. Shah, chief medical officer at digital health company Maven Clinic.

Advertisement

State action, yet not enough

Inequality in access to fertility treatment has been part of the Massachusetts health care landscape for decades. On Dec. 28, 1981, the first “test tube baby” in the US was born to Judith and Roger Carr of Westminster, north of Worcester. But the science was then so new, and the political and religious climate around IVF in Massachusetts so fraught, that the procedure and birth took place at a research university in Virginia.

Judith Carr held newborn Elizabeth on Jan. 4, 1982, the nation's first baby conceived with IVF. (George Rizer/Globe Staff)

The news of baby Elizabeth Carr — 5 pounds 12 ounces and ‘’perfectly healthy” — made worldwide headlines, and within a few years, IVF clinics sprouted. By 1987, 158 were open across the US, including private centers in Brookline and Newton. But the new procedure didn’t come cheap. “Patients at one leading IVF center say most of the women there are so visibly wealthy that the waiting room has a ‘country club’ ambiance,” a Globe reporter observed that year.

The Massachusetts mandate was in large part designed to address the inequity. “If we are going to have this kind of technology,” a Boston physician advocating for the bill said at the time, “it’s not fair that some people should have it and others should not.”

Maryland was the first state to require coverage of IVF, in 1985, but Massachusetts went further two years later, including all aspects of infertility diagnosis and treatment. And Massachusetts has added to the mandate in the decades since. In 2010, lawmakers improved access for women over 35 and required insurers to count miscarriages toward the length of time a woman had been trying to conceive. In 2024, another law required coverage of fertility preservation when “medically necessary,” such as when a cancer patient needed chemotherapy that could render them infertile.

But nearly four decades on, the exclusion of Medicaid members persists.

Medicaid is the primary reason people lacked infertility coverage in Massachusetts. Approximately 21 percent of women between the ages of 20 and 44 residing in the state — or 247,569 people — lacked fertility coverage in 2019 because they had MassHealth insurance.

These gaps primarily affect working-class families and individuals with disabilities and disproportionately impact people of color. Nationally, Black and Hispanic people make up under a third of the total population, but nearly half of the people using Medicaid.

The mandate also doesn’t apply to most large employers: Companies are exempt if they pay their own claims. Though many “self-insured” employers provide fertility benefits anyhow, some don’t, and available state data show fewer are doing so every year. In 2019, federal employees also did not have coverage.

As a result of these carveouts, more than a quarter of Massachusetts women of reproductive age likely had no fertility coverage in 2019. Though federal employees have since gained coverage, self-insured employers have been cutting back, and the overall coverage numbers have thus likely worsened.

Another 5 percent of women of reproductive age in Massachusetts had limited coverage in 2019.

The number of Massachusetts residents without coverage is likely even higher than these estimates. The data looked only at women, but other would-be parents – including same-sex male couples and transgender people – also encounter fertility challenges and require treatment.

While Massachusetts was a trailblazer in its day, it has fallen behind other states in broadening access for those on public insurance. New York, Utah, and Washington, D.C., cover some fertility treatments for Medicaid patients. And Illinois, Maryland, Montana, Oklahoma, and Utah all offer Medicaid users some form of fertility preservation.

“One of the most obscene [issues] we still debate is the Medicaid [exclusion],” said Marjorie Clapprood, one of the original sponsors of the 1987 law. “That means if you are poor and can’t afford it, you don’t get access to IVF.”

Advertisement

The MassHealth gap

In some ways, MassHealth has offered Olaide Adekanbi freedom.

Now 30, she has lived her whole life with sickle cell disease. The genetic mutation, which primarily afflicts Black people, transforms her red blood cells into crescent moons, which feel like tiny knives as they work their way through her bones.

“I open my eyes and it’s pain that says good morning,” she said.

At times, the pain is a dull ache, lingering in the background. Other times it can explode into a flare so excruciating it demands her full attention.

The symptoms, which worsen with age, led Adekanbi to leave college in her final year and move to New York to live with her mom. Now living in Dorchester, she has given up her dreams of being a molecular biologist, focusing when she can on entrepreneurship and advocacy work for people with sickle cell.

A measure of hope for those with the disease arrived in 2023, when two different gene-editing therapies were approved to treat it. The grueling treatments last 12 to 18 months and include chemo and a bone marrow transplant.

The idea of a life without pain is enticing, but there’s a catch. Ninety to 95 percent of patients who undergo the new treatments are rendered infertile. And though MassHealth will pay for Adekanbi’s gene therapy, which costs in the millions of dollars, it will not pay to preserve her eggs ahead of it — which without drugs costs less than $10,000.

For so long, Adekanbi was just focused on staying alive. But she’s now in a serious relationship and wants a future that includes a family. The choice she confronted didn’t feel fair.

“They ask us, ‘What are you willing to give?’” Adekanbi said. “What is ethical? What is right for people to ask you to give up? Your chance of starting your own family?”

Olaide Adekanbi, shown at the Massachusetts State House, has had to debate between being a mom, or exploring gene therapy to treat her sickle cell disease. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

To Massachusetts residents with commercial insurance, this isn’t a choice. They can typically freeze their sperm or their eggs at the expense of their insurers, thanks to the state’s new fertility preservation law, largely pushed by the Massachusetts Sickle Cell Association. Government insurance still has no such requirement, though a pending bill could change that.

For now, Adekanbi has decided to forgo gene therapy. There are few long-term studies on it, and the sacrifice feels too great. And even if she did find a way to freeze her eggs, MassHealth would not pay for the IVF she’d need to eventually use them. What does it mean to have an improved quality of life if it didn’t include the possibility to have the full pieces of life? she wondered.

The risk of infertility has been a major stumbling block for many sickle cell patients weighing the new treatments, said Dr. Sharl Azar, a hematologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. There are about 600 sickle cell patients of reproductive age on the state’s Medicaid plan.

Adekanbi is confident she’ll make a great mom one day, even with a debilitating condition. Her voice cracked as she talked about it. “We should be able to have human dreams, and execute them, in the way the society we live in and contribute to has already made available – but not available to us,” she said. “We’re just asking for barriers to be removed.”

What MassHealth covers — and what it doesn’t — communicates a message, said Nicole Lomerson, a research associate at the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy at Brandeis University. She notes, pointedly, that state insurance will pay for procedures and drugs that prevent pregnancy, from birth control to tubal ligation.

“I’m not accusing MassHealth of engaging in eugenics,” Lomerson said. “However, these policies have larger implications. The policies we make say something about what we as a society value.”

Most people qualify for Medicaid because their income is below a specific threshold, which in Massachusetts for most adults is 133 percent of the federal poverty level. In addition, Medicaid is the primary insurer for people with physical, developmental or behavioral disabilities.

The state, however, doesn’t collect data showing how many individuals with disabilities use assisted reproductive technology, which is telling in its own way, advocates say. Gathering this information “would require recognizing that people with disabilities are sexual beings who want to reproduce,” said Robyn Powell, senior research associate at the Lurie Institute.

The limits on Medicaid come on top of systemic and structural inequities that make it harder for individuals with disabilities and people of color to access infertility care. Studies show Black women wait longer than white women to see specialists and encounter higher rates of physician bias. Individuals with disabilities confront a host of hurdles as well, and they are twice as likely to live in poverty.

The current state of fertility coverage in Massachusetts “feels like an ethical quandary to me,” Lomerson said. “It feels like we’re picking winners and losers in the quest to have a child.”

A promised land for some, but not all

The Massachusetts mandate has undeniably helped many people with their fertility challenges. In 2022, the most recent year with available data, about 3,900 of the nearly 69,000 infants born to Massachusetts residents were conceived with the help of assisted reproductive technologies. That’s 5.6 percent, more than double the national average, and the highest rate of any state.

The mandate has also encouraged broader adoption of benefits among employers who aren’t required to provide them. Most self-insured employers here offer fertility treatment; it is widely seen as a necessary benefit to attract top employees. There are signals that may be changing, though.

“It feels like we’re picking winners and losers in the quest to have a child.”—Nicole Lomerson, research associate at Brandeis University

Nationally, self-insured companies are increasingly offering IVF coverage, but available Massachusetts data show the opposite trend. In 2017, 82 percent of the nearly 3 million people working for self-insured companies that filed reports with the state had full IVF benefits, according to the Division of Insurance. By 2024, that had dropped to 78 percent.

Even so, women in many other states tend to look at their counterparts in Massachusetts with envy. Just over two-thirds of states require no IVF coverage at all.

When she was going through IVF, Michelle Mani of Dedham recalled seeing women on Facebook sharing their challenges and considering herself lucky to be here. She remembers calling her insurer six years ago to verify her coverage and gasping when she was told the news — there were no limits to her plan. Almost everything would be covered.

She gave birth to her second baby in March. Both arrived with the help of IVF.

But even with excellent fertility coverage through her husband’s insurer, the process was by no means free. Over five years, Mani’s out-of-pocket bills totaled more than $9,600. Still, she feels fortunate. Her co-worker with less robust coverage, going through the same journey with the same doctor, has already spent over $10,000 just for genetic testing and still hasn’t gotten pregnant.

Without insurance coverage, the costs for fertility treatments can be astronomical.

What is assisted reproductive technology — and why is it so expensive?

Fertility treatments can cost patients without adequate insurance coverage tens of thousands of dollars. Here's a look at common scenarios and how much they cost.

- Initial consultation: $300-$500

- Fertility testing: $1,500-$3,000

- Ultrasound monitoring: $1,500-$2,500 But it doesn’t end there.

- IVF (blood work, clinic visits, ultrasound, anesthesia, sperm preparation, egg retrieval, fertilization, and fresh embryo transfer): $15,000-$20,000

- Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection, or ICSI: $1,500-$3,000

- Medication: $3,000-$8,000

- Embryo freezing: $1,000-$2,000

- Annual storage fees for unused embryos: $600-$1,200

- Frozen embryo transfer: $4,000-$6,400

- Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT): $4,000-$8,000

- Sperm acquisition (doesn’t include storage costs): $1,000-$2,000 a vial, plus $100-$300 for shipping

- IUI (monitoring with ultrasound and blood tests, sperm preparation, insemination): $2,000-$3,000

- Medications (if needed): $500+

- Donor egg acquisition (typically in batches of six to eight eggs): $14,000-$47,000+

- Gestational carrier (Agency compensation, screening and selecting the carrier, legal fees, and medical costs): $10,000-$150,000+

One national study found that IVF put more than 30 percent of surveyed individuals into debt of more than $20,000, even though roughly half of them had some fertility coverage.

Some pay far more than that, like Dr. Jamie Adler of Needham.

In July, Adler looked at the sonogram and considered what it had taken to get to that point. So far, this baby – still a fetus, really – had cost her nearly $300,000.

Adler was 34, single, and fresh off an emergency-room residency in 2018 when she realized she should start thinking about her fertility. She’d been putting her prime child-bearing years on hold to care for patients. Her insurance didn’t cover freezing her eggs without a medical reason, so she decided to pay $36,000 for two rounds of the retrieval procedure. Storage of her eggs cost another $110 a month.

When Adler’s mother died three years later, her desire to start a family intensified. As a single parent, she had to pay $8,000 for donor sperm to fertilize the eggs she froze. It cost another $6,000 for genetic testing of the embryos she created.

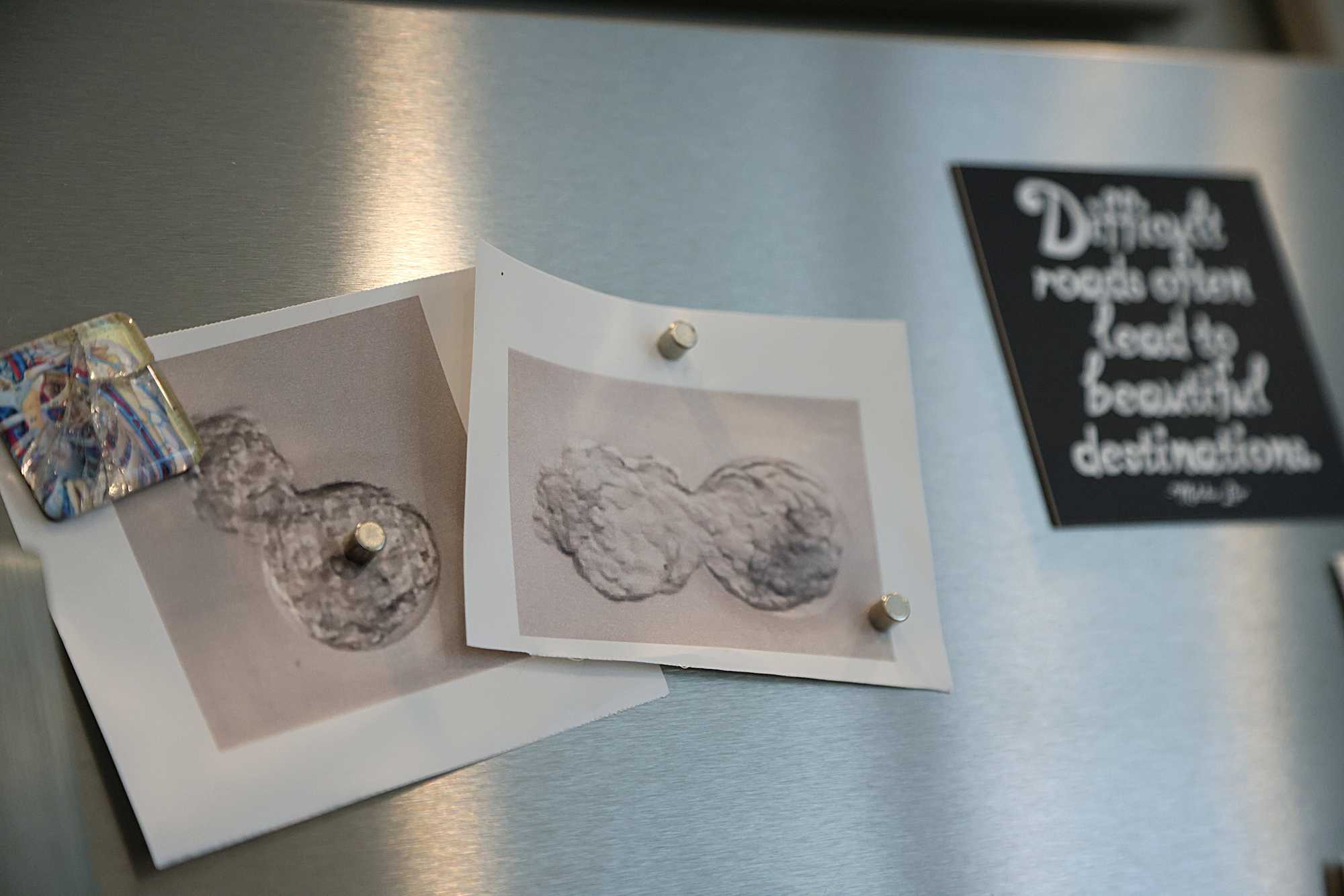

A photograph of Dr. Jamie Adler’s daughter, Coco, when she was an embryo on the day of transfer to a surrogate. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

A year earlier, Adler had been diagnosed with endometrial cancer. But with the cancer in remission, Adler chose a date in November 2023 to transfer the embryos, the culmination of years of planning. Then a precautionary biopsy discovered something alarming: The cancer was back. On the day she had scheduled her IVF procedure, she instead had her uterus removed.

After her surgery, Adler was still determined to have a child — now with a surrogate carrying her baby. Like most insurers, her health insurer would pay nothing toward that $200,000 cost. She borrowed money and started working extra shifts in the emergency department to save.

In late June, Adler flew to Minnesota, where her surrogate lived, to await the birth of her daughter. She hung a strip of 3D ultrasound photos in her hotel room, the baby’s round cheeks already visible. She’d named her Coco.

Adler is grateful to have the sort of job and resources that have allowed her to afford all this. She recognizes none of her patients with MassHealth, and relatively few with private insurance, would be able to do what she’s done. She also cannot afford to do it again.

“She is the best thing in my life. I would pay any amount of money to be her mom and have her here," Dr. Jamie Adler says of her newborn, Coco, in their Needham home. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Guests at Adler’s shower signed diapers for her 2-week-old daughter. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Was it all worth it?

“1,000 percent,” Adler said. “She is the best thing in my life. I would pay any amount of money to be her mom and have her here. There is no limit to what I would have paid for her.”

A ‘heterocentric approach’

Hannah Connor and her wife, Kara, are used to taking big leaps of faith, trusting their instincts and resolve. That’s how it was when the couple decided to start trying for a baby — they both come from big families and always knew they wanted children.

“It’s funny, because the little things we take forever to decide about, we’ll argue about it,” Hannah said. “But the big things were like, ‘Yep, let’s do it.’”

The decision to start a family was easy, but trying to get pregnant hasn’t been. Under Kara’s insurance, the couple needed to “prove” their infertility before they could access IVF. The insurer required five rounds of intrauterine inseminations first, in which sperm is placed in the uterus by a clinician during ovulation. It would be up to the couple to pay for the sperm.

Kara and Hannah had been working second jobs, but the $8,000 they set aside didn’t go far. One donor they had been using upped his price from $1,250 a vial to more than $2,000.

Kara and Hannah Connor, at their home in Fall River, have spent more than $25,000 on fertility treatments. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

The state’s two largest insurers have recognized that their policies create additional financial burdens for LGBTQ couples and single people who want kids. Starting almost two years ago, Harvard Pilgrim began providing coverage for donor sperm for intra-uterine insemination (IUI), IVF, and reciprocal IVF — in which one partner contributes the eggs and a different partner carries the pregnancy.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts said that, starting next year, it plans to offer benefits for donor sperm for single women and same-sex female couples, for example, and allowing lesbian couples doing reciprocal IVF to skip the IUI process.

While the insurers’ updated policies might help patients afford the cost of sperm, it would often still require them to go through IUI to prove they cannot get pregnant.

Insurers say the process is designed to achieve a pregnancy in the easiest and cheapest way. “If you don’t have any infertility issues, and the issue is you aren’t exposed to sperm, you might have a good chance of conceiving with IUI,” said Dr. Monica Ruehli, medical director at Blue Cross.

But Davina Fankhauser, executive director of the advocacy group Fertility Within Reach, said it doesn’t necessarily save money to have women go through multiple rounds of IUI before they can qualify for IVF.

Efforts are underway for a more holistic change, with multiple bills this legislative session proposing updates.

Codifying rules is critical to ensure broad access, Fankhauser said. “When things are voluntary, it’s inconsistent,” she said. “When a patient is denied, if it isn’t part of statute, it isn’t part of the insurance regulations, then the Division of Insurance can’t really step in and help people. By having things in a clear statute, they are then able to better protect patients when they are wrongfully denied.”

State Senator Julian Cyr has a pending bill that would update the definition of infertility to be more inclusive of LGBTQ families. The legislation would also require MassHealth to cover some fertility treatments and put timelines on how long insurers must pay for fertility preservation storage.

The issue is personal for him. A family member and their spouse used a friend as a sperm donor and chose to be inseminated at home to avoid the clinic process. Cyr himself was a sperm donor for friends.

“When it comes to family building, the medical care, insurance coverage, entities that help you conceive have this deeply hetero-centric approach,” Cyr said. “In a world where about 20 percent or more of Gen Z are identifying as LGBTQ in some way, and families look different, things seem woefully out of date.”

Changing the definition of infertility to one that is more comprehensive of those needing medical intervention would put Massachusetts in line with the best practices set out by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. It would also bring it in line with other peer states, including Illinois and California.

The burdens of IUI have only been the beginning for Kara and Hannah. After three years of trying IUI — and spending more than $25,000 — they could theoretically move on to IVF. The IVF process could allow Kara to donate eggs, and Hannah to carry any resulting embryos, though they would still need to pay for sperm out of pocket.

As an alternative, they are looking at doing insemination at home or at a hotel using sperm from someone they found online.

Hannah was talking to three potential donors on Facebook. She kept things professional. Have they had success with other women? How many times would they be willing to donate in a given fertility window?

“It feels like I’m on the black market for body parts,” Kara said. “Some guy is sending us sperm in the mail. It’s ridiculous saying out loud.”

Though typically decisive, Kara was waffling. Unlike going through a sperm bank, there were no genetic tests done when you met up with donors informally.

But by meeting up with a potential donor in a hotel, using a syringe to inseminate, the couple could try multiple times in one fertility window. They could try to get pregnant basically for free.

The costs had already affected the couple’s lives. It took them longer to buy a house. They had to get rid of their second car.

Hannah got a second job at Starbucks, rising as early as 2 a.m. some mornings to work a shift before her regular 9-to-5 job. It brought in a bit of extra money, but it was also an insurance backup plan. Starbucks offered robust fertility benefits to employees who hit certain hours. If Hannah worked more, the insurance would be there.

Kara and Hannah Connor still have a wrapped baby blanket they had placed under their Christmas tree three years ago. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

When they first started trying to get pregnant, the couple bought a baby blanket and placed it under the Christmas tree — as if manifesting the child they longed for. Wrapped in cheerful “Let It Snow” paper, the gift has now made an appearance for three Christmas seasons.

Kara sometimes slipped into daydreams of what might have been if any of the pregnancies had stuck. They might have had a 2-year-old by now.

The pair looked around at the life they had built — they owned a house, they both loved their jobs, they had supportive families. There was so much to be grateful for.

And yet.

“I’m getting triggered a little bit when I see 2-year-olds out and about,” Kara said. “I’m like, ‘That could be us. It should be us.’”

Kara and Hannah Connor are trying to decide what steps to take next -- and how to pay for them. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporter: Jessica Bartlett

- Editors: Gordon Russell, Francis Storrs

- Photographers: Suzanne Kreiter

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video producer: Jackline Luna

- Director of video: Anush Elbakyan

- Development and graphics: Kirkland An

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Illustrations: Luis G. Rendon

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC