Once a shining beacon, White Stadium has a history marred by violence and neglect. What legacy does it leave?

White Stadium, nestled inside Boston's Franklin Park, has been the home of the city's public school athletes since its opening in 1949. But it has become an eyesore, left to decay as teams play in front of sparse crowds. A renovation aims to restore the former glory by the time the NWSL's Boston Legacy take the field in 2027. (Evan Richman/Globe Staff)

As it is overhauled to host professional women’s soccer, the 76-year-old venue has become a political football. Turns out, that may have always been the case.

IIt took decades to achieve with heaps of political squabbling along the way.

When the George Robert White Fund Schoolboy Stadium finally opened in 1949, it was a gleaming gift to Boston’s high school boys, in a time when they were the only young athletes society championed.

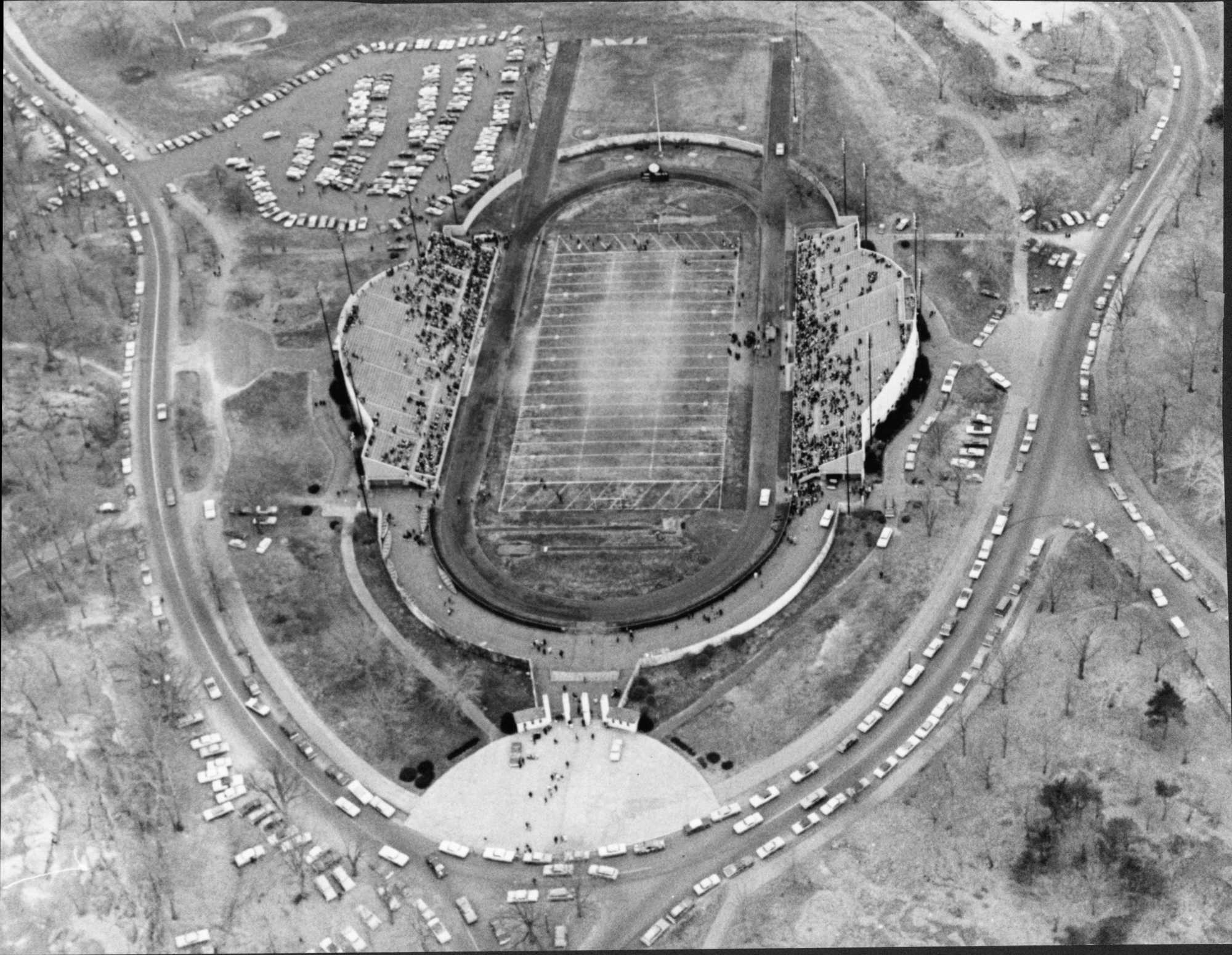

The new clamshell structure in Boston’s largest public park, at the intersection of Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, and Roxbury, was hailed as the finest school stadium in the nation. Football doubleheaders drew from all corners of the city in the 1950s and ’60s.

But the magic didn’t last.

As locals ran, played, and watched events there, White Stadium began to crumble. It has spent its last 60-odd years neglected by the city and ignored by everyone else.

“I mean, it was beat down,” said Terry Cousin, a longtime youth football coach for the Dorchester Eagles.

The name carved into White Stadium’s Art Deco facade was rendered obsolete when girls first took the field. Soon, it will become just the second stadium built primarily for a women’s soccer team, when the NWSL’s Boston Legacy FC begins play there in 2027.

The proposed public-private partnership, ushered through — with some controversy — by Mayor Michelle Wu and the City of Boston, will also allow significant access to Boston Public Schools athletics programs, including high school football.

The Legacy’s new home will build on a history that is long, proud, and at times violent, with rock-and-knife fights interspersed with some fantastic football.

There were Eisenhower-era Thanksgiving battles between intercity rivals, where the stadium would overflow its 10,000-plus capacity. And a 1991 game between East Boston and South Boston, both teams 9-0 and a state Super Bowl berth on the line. White Stadium also produced its share of track standouts, such as Dorchester’s Calvin Davis, a bronze medalist at the 1996 Olympics.

“It was the mecca,” said Clarzell Pearl, a football star at English from 1986-90. “You were the show. You were talked about all week if you played at White Stadium.”

Clarzell Pearl, English High football player, 1986-90

East Boston fans celebrate a touchdown against South Boston during their 1998 Thanksgiving Day rivalry game. (John Blanding/Globe Staff)

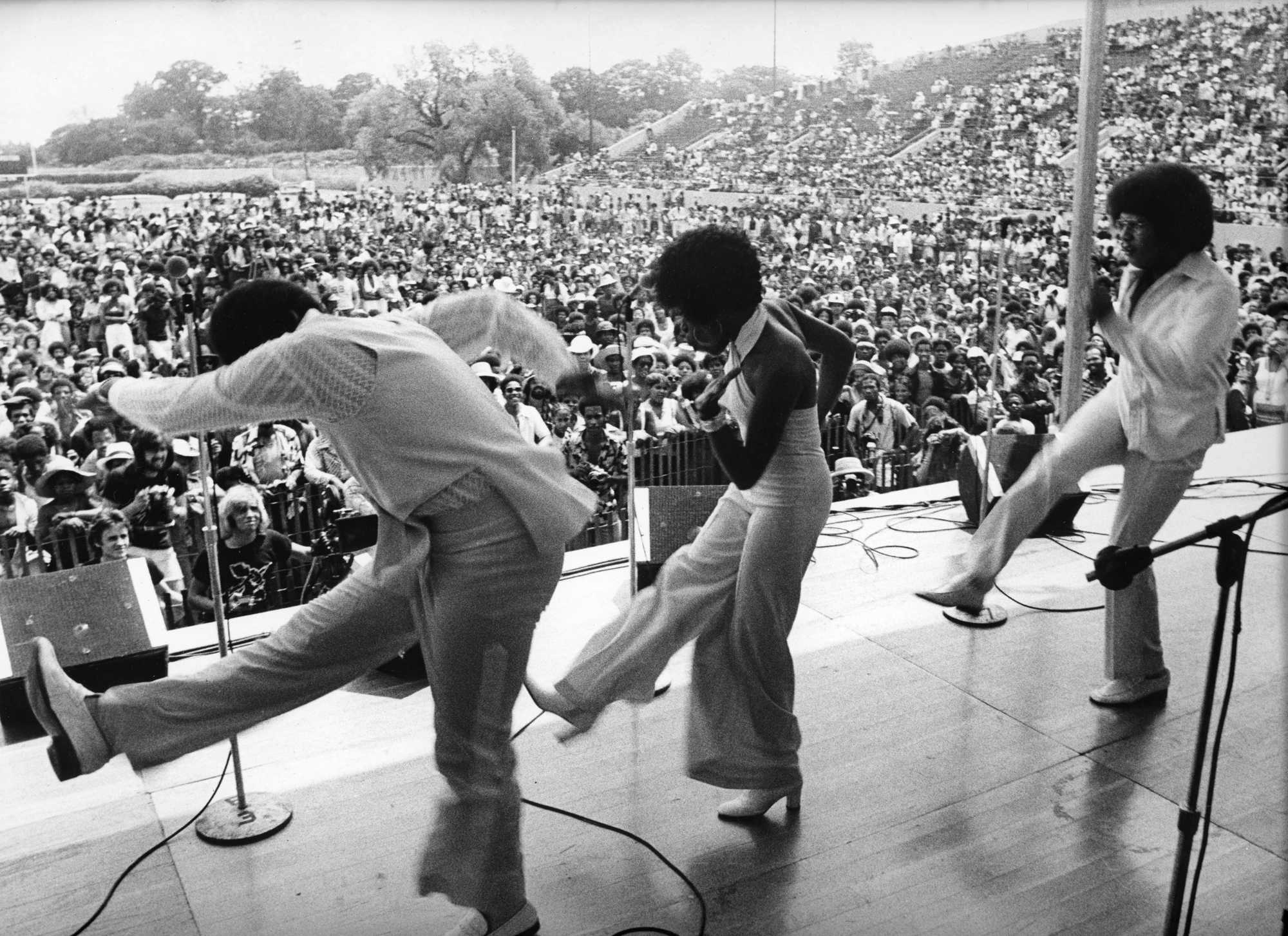

People who have loved White Stadium for generations still talk about the Uptown in the Park concert series in 1974. Held to benefit the arts school run by the indefatigable Elma Lewis, it turned out an estimated 55,000 over two shows.

On July 7, Sly and the Family Stone headlined, supported by Tower of Power. Richard Pryor, realizing his considerable might as a performer, did a comedy set. On Aug. 25, it was Funkadelic along with the Isley Brothers, Gil Scott-Heron, Mandrill, and the Bar-Kays.

“There was nobody home in Dorchester and Roxbury,” said Rickie Thompson, a lifelong neighborhood resident and president of the Franklin Park Coalition, who ran track there while competing for English High. “We filled that whole stadium to the top. We covered the whole football field.”

Advertisement

A few weeks later, the busing crisis threw the city into discord. That year, for the first time, White Stadium didn’t host a Thanksgiving game. Mayors throughout the 1980s and ‘90s sought substantial funding to revitalize the field, and the city’s youth teams, with little success.

Now, demolition on White Stadium is nearly complete, its renovation delayed by lawsuits from neighbors concerned over noise, parking, and disruption.

As it enters a new chapter, what is the legacy of this place?

The answers have changed over the years. And they have always depended on whom you ask.

A civic battle to build

Long before White Stadium existed, it was used as a political football.

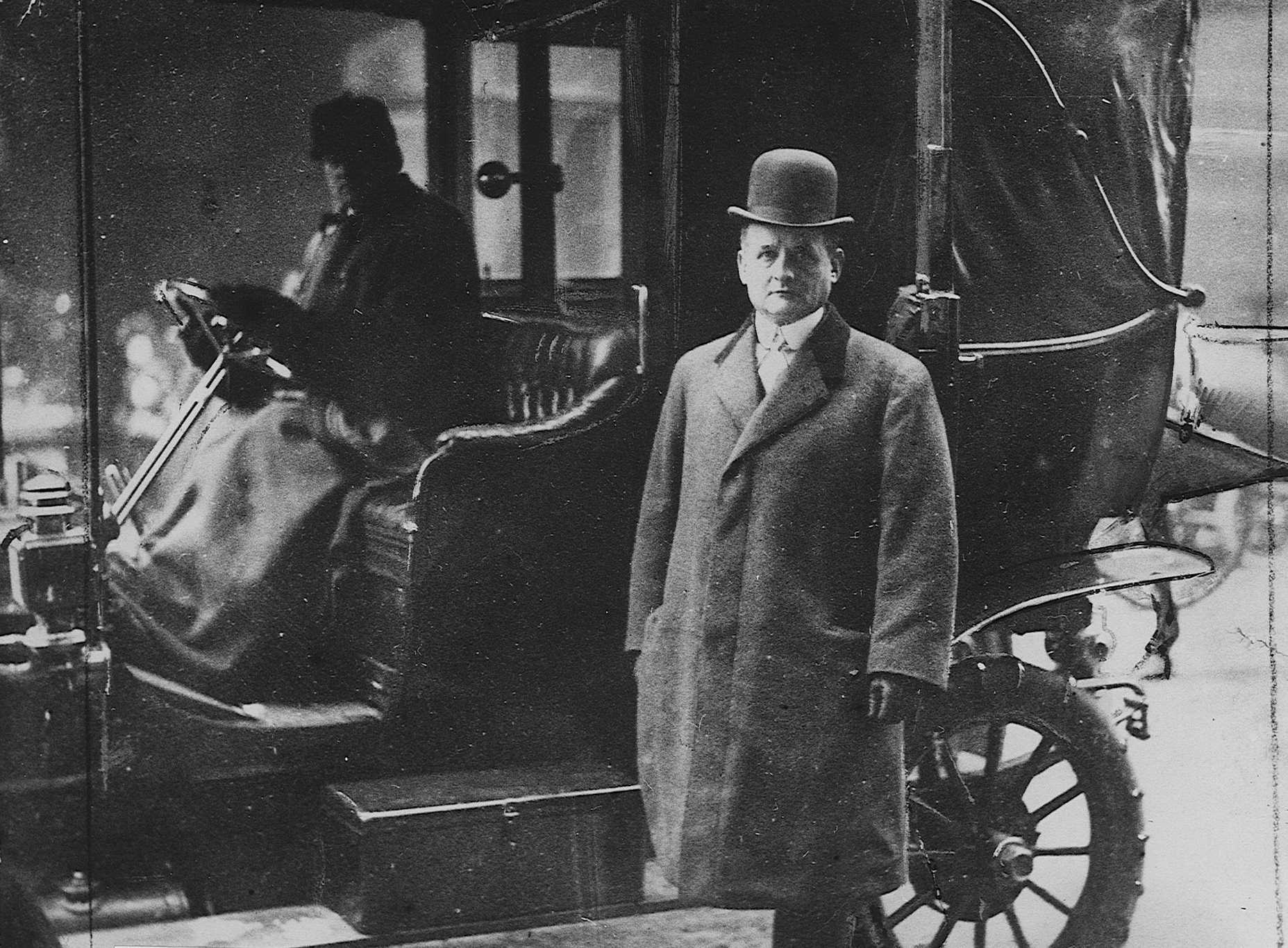

Circa 1907, Mayor John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald supposedly proposed a new stadium for high school football. Politicians batted around the idea for decades.

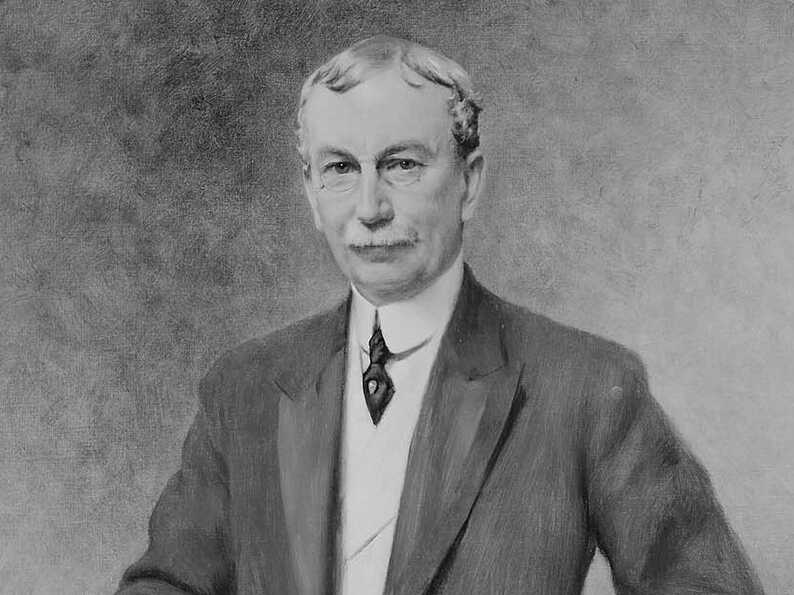

George Robert White, who died in 1922, left $7 million to create “works of public utility and beauty” for Boston residents. Several proposals were shot down, but resistance to fund a sports stadium waned amid the postwar boom, as families and cities rapidly expanded.

Boston Mayor John F. "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald in 1910. (Globe File Photo)

The story of White Stadium through the Globe’s archives

In 1907, a half-century before White Stadium opened, Mayor John F. Fitzgerald proposed a schoolboy stadium while attending the Latin-English game at the Locust Street grounds in South Boston, near what is now Moakley Park.

Jan. 27, 1922

George White dies at 74, leaving a permanent fund for Boston residents. Born in Lynnfield to Irish immigrants, White went to Acton public schools and abandoned plans for college after his father died in the Civil War. He became a partner at Weeks and Potter, a Boston drug company, and made a fortune with a medicinal soap. White left $7 million ― more than $91 million in today’s dollars ― to the city of Boston.

July 25, 1947

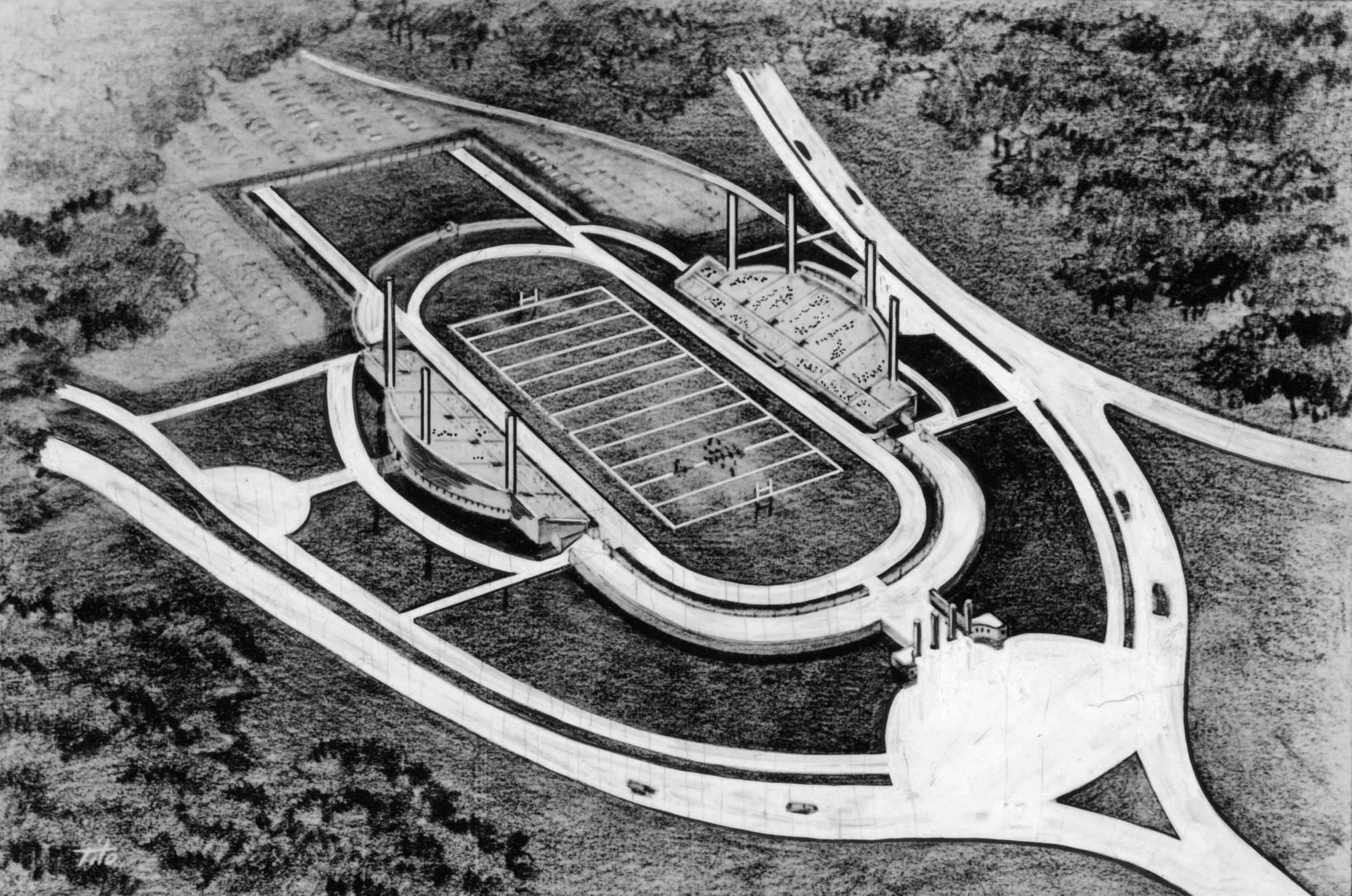

A proposal for three stadiums on public playgrounds ― Healy Playground in Roslindale, Fens Stadium, and Strandway Stadium in South Boston ― became one. Temporary Mayor John Hynes said the city was prepared to move forward with a single stadium in Franklin Park, seating 12,000-15,000, at a $300,000 cost.

By 1947, Boston had college and professional teams of all kinds but was the only major city in the country without a proper high school football stadium. When they weren’t blinded and coughing in the dusty Fens, the city’s dozen teams were tearing up Fenway Park and Braves Field and battling for playing time with collegians and pros.

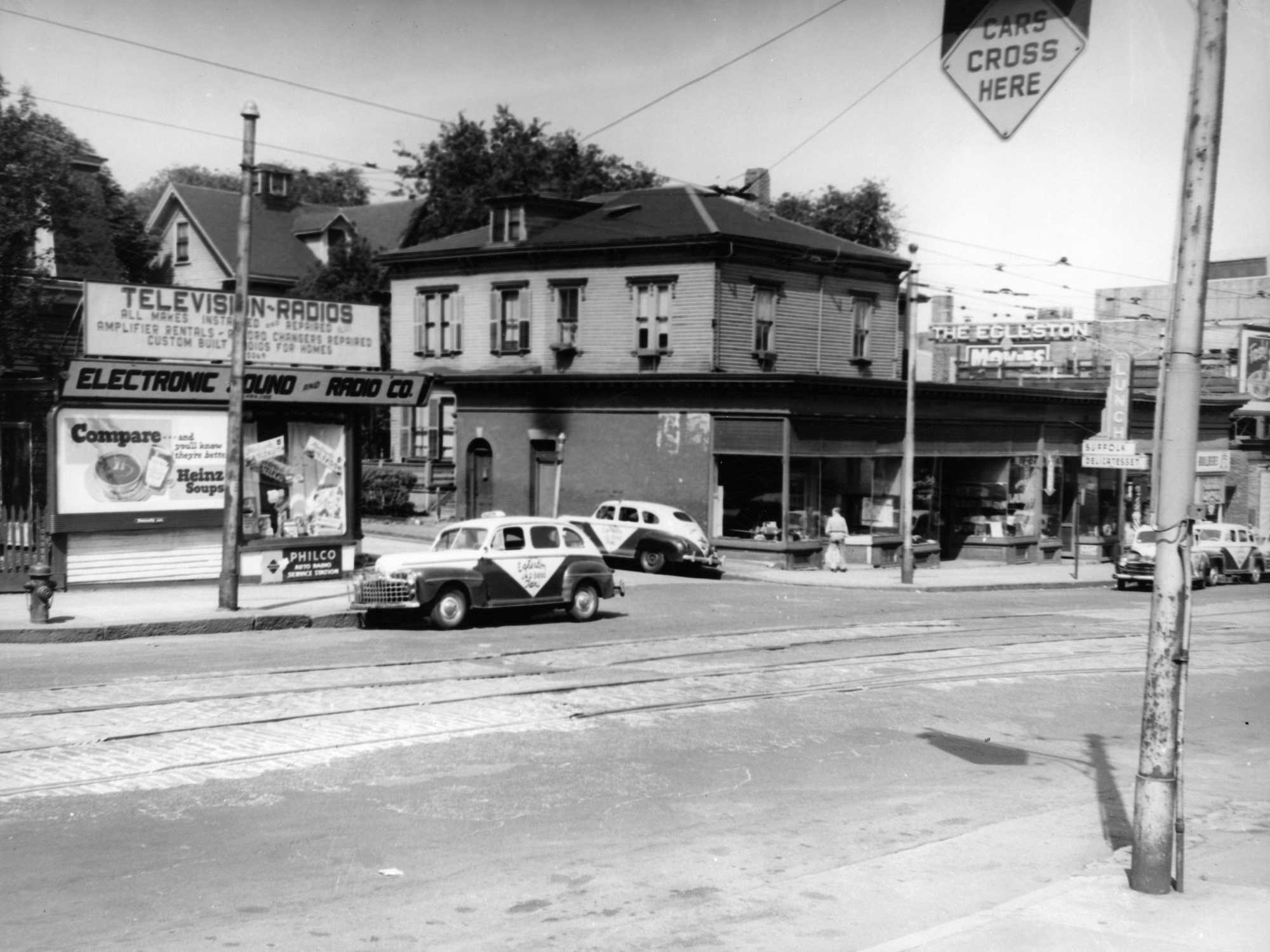

The city settled on a high-sloped hollow bordering Egleston Square, surrounded by electric street trolleys on Seaver Street and Blue Hill Avenue and the elevated railway on Washington Street.

The stadium, designed by Desmond & Lord, was originally said to be ready in the spring of 1948, but it wouldn’t open until the fall of 1949. Plans called for a larger and cheaper stadium than what was actually built: 10,000 seats, at a $1 million cost.

Late, lacking, and over budget. As usual, politicians bickered over the blame. Sound familiar?

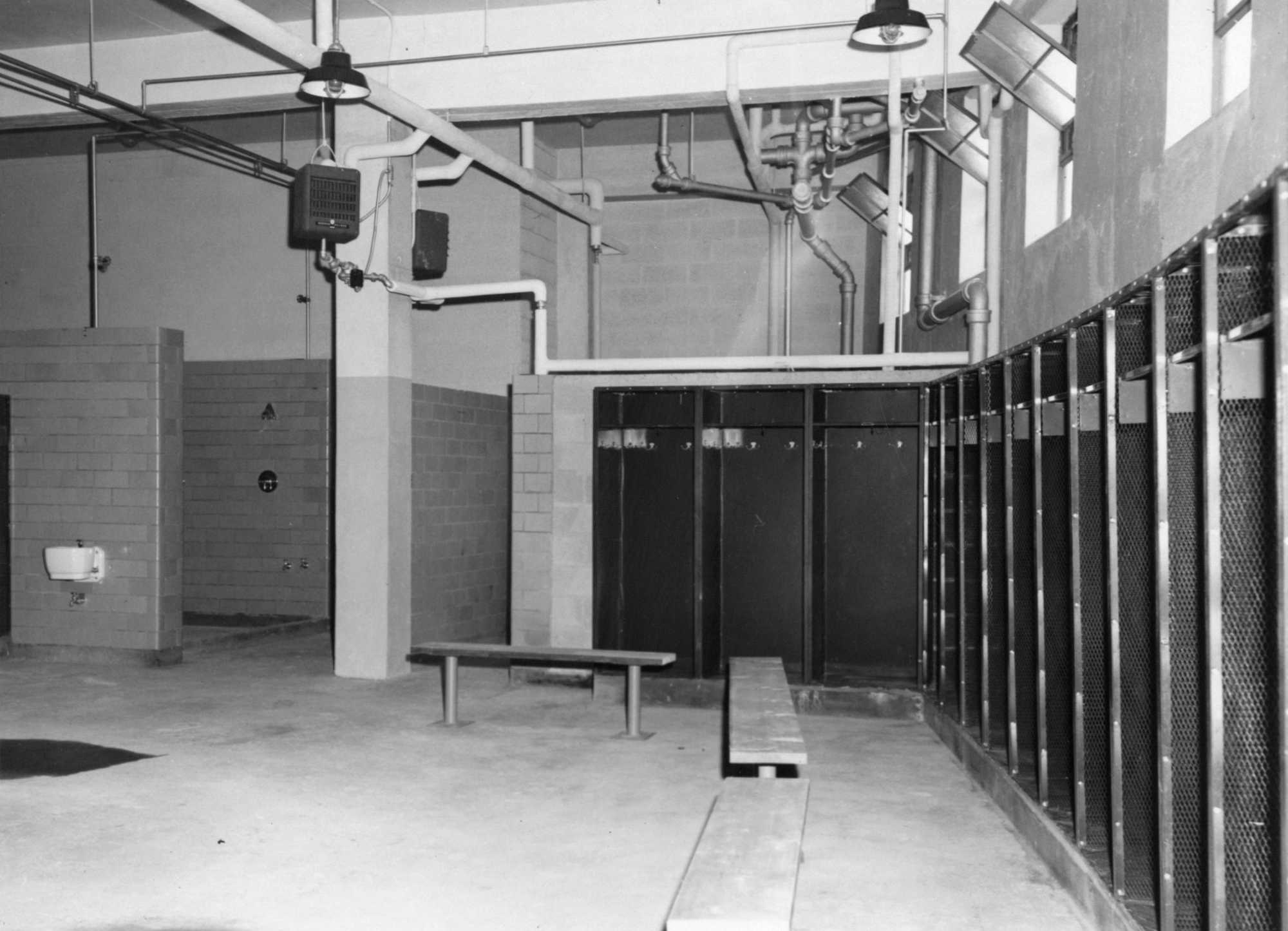

The city spared no expense for White Stadium, building a professional locker room modeled after the one at Yankee Stadium. Here is a look inside in September 1949, right before the venue opened. (Boston Globe Archive)

Feb. 5, 1949

The White Fund trustees said that when the stadium is completed and turned over to the city in April, they would recommend that it be rented for “commercial sports exhibitions” to offset an annual $100,000 maintenance cost. “Unless such a program is followed,” one official said, “this project will become a white elephant for the city.”

Feb. 8, 1949

Nope, said Mayor Curley. There would be no “other attractions” at White Stadium ― only sporting events, and schoolboy contests would have priority. A week later, the White Fund trustees agreed to rent the stadium to defray upkeep costs. Days later, Globe sports editor Jerry Nason wrote in a column he agreed with Curley’s protecting the grounds for kids. Nason called it “the single greatest contribution to scholastic athletics in this city during the past 50 years … a lot of lip service and little else is paid to the Boston schoolboy.”

Sept. 14, 1949

Opening a campaign to oppose Curley, John B. Hynes called the sitting administration “the most wasteful and extravagant in the city’s history.” Hynes, who was temporary mayor when the million-dollar project was launched, said it was his idea — and it was originally supposed to cost up to $400,000. It was now pegged at $1 million. He beat that drum for a month in newspaper stories, even though Curley, who served four terms as mayor from 1914-55, had long talked about the need for a schoolboy stadium.

Well before the ribbon-cutting, everyone wanted a piece of White Stadium. As 1949 turned from spring to summer, vandals were all over the construction site. Children were “running wild,” and had tried to rip out the plumbing. Officials made pleas for a 24-hour watchman.

But for those who longed for a stadium, victory was in sight.

No more doubleheaders every afternoon of the football season, or track championships having to yield for baseball games at BC’s Alumni Field. No more rainouts in moderate weather. Night football games, the best track in New England, and sparkling locker rooms.

For those allowed to use it, it was a breath of fresh air.

Advertisement

A magnificent wonder

“Ouch!”

Globe schools editor Ernie Dalton asked readers to excuse him, as he pinched himself.

“Why shouldn’t I?” he wrote triumphantly in the Sept. 15, 1949, editions of the Globe.

Dalton was crowing about the new era, having played football at South Boston for four years and wrote about schools sports for 25. He walked miles, “in dust, rain, heat and cold,” at the old Walpole Street grounds, at “that transplanted Kansas dust bowl, Fens Stadium,” at the old McNary Playground in South Boston, Rogers Field in Brighton, World War Memorial Park in East Boston, old National League Park off Walpole Street, and frigid Strandway Stadium by the water.

This place, Dalton wrote from a heated press box, left nothing to be desired.

White Stadium borrowed elements from famous fields of the time: the “turtleback” design of Brown’s Aldrich Field, where the center of the field was its highest point; the IBM scoreboard from Notre Dame, track specs from Harvard, irrigation system from Yale and grass grown in Rhode Island. The dressing rooms were patterned after Yankee Stadium.

There were program booths under the stadium (“Programs at Boston games!!!” Dalton wrote). Four booths, actually. Five light towers for night contests. Six concession stands, with a kitchen to keep them supplied.

It was large enough to hold 10,519. It had 16 turnstiles emptying into 24 gates with 10 ticket windows. The parking lot could hold 2,000 cars. It was a three-minute walk from Egleston Station, and a half-minute walk from the nearest trolley stop.

There were four flagpoles, one at each corner, to fly the flags of each school in a football doubleheader, which would be held on Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays.

What else? An electric scoreboard and clock, a public address system, rooms for officials, trainers, and first aid, and office space for management; four dressing rooms with 33 lockers, eight showers and toilets in each.

The facade of White Stadium, built in the Art Deco style, features a sculpture of its intended use: schoolboy football. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

The field had a built-in sprinkler system, ample bench space, and a practice field on the other side of the scoreboard. The stadium was circled by six cinder racing lanes — according to Dalton, the “only genuine track in the city.”

Every inch of the grounds, inside and out, was well-lit.

“I never thought the day would dawn,” he wrote, “but it has.”

Advertisement

Opening day

After a two-day rainout (Latin-Commerce and English-Roxbury Memorial was the first canceled bill), it was game on.

Defense won opening day at White Stadium, on Sept. 30, 1949. The first scores:

· Roslindale over Charlestown, 19-0

· East Boston over Brandeis Vocational, 13-0

· Hyde Park over Brighton, 13-7

· South Boston over Jamaica Plain, 12-0.

Admission for students was 25 cents (about $3.27 today), and 50 cents for adults for afternoon games, $1 for night and holiday games ($6.55 and $13.10).

Folks were gushing about the place.

In October 1949, the school committee hosted a group that wanted to build their own version in Japan. Five years later, a delegation from Dallas visited White Stadium to study the state-of-the-art amenities.

The view of White Stadium from the press box at its opening in September 1949. (Boston Globe Archive)

Sept. 30, 1949

After rain delays the festivities on Sept. 16, eight teams gather to open White Stadium. A month after its opening, a Japanese visitor came to observe and document the venue as his country began plans to build sports stadiums after the war. By November, a school committee member was pleading to make the stadium self-supporting and another wanted it open to the public.

November 1950

The Boston school football physician, Dr. Joseph Burnett, reported that the number of football injuries — “frightfully high” at previously used fields — were down. “Find me a school or college setup that compares with it,” Burnett said. “You never will. Not even if you travel all over the country. Best there is.” The level of play had improved as well. “The reaction alone of the players makes White Stadium the greatest thing that ever happened to us,” Boston schools athletic director Joe McKenney said.

April 19, 1953

School buildings aren’t as sparkling. Amid the postwar baby boom, Boston’s school population exploded and its building stock was aging. The school committee asked Harvard to study all 221 public school buildings, and nearly all of them needed major work. A third were at least 50 years old. They were mostly steam-heated, using coal shoveled by hand, and poorly lit and ventilated. Harvard recommended 57 of the 221 buildings be shuttered. But White Stadium was shining.

On Thanksgiving Day 1950, the Latin-English game made its White Stadium debut. An estimated 500,000 people watched it on WBZ, the first TV broadcast of the oldest high school football rivalry game in the country.

The level of Boston school football had improved considerably, observers said. “The reaction alone of the players makes White Stadium the greatest thing that ever happened to us,” said Joe McKenney, then-head of BPS athletics and the driving force behind the project.

There were no more bystanders on the field. No cuts from shattered glass. No broken legs from holes in the turf. After every game, cleat marks were brushed out and the field was rolled and freshly marked.

In track, all 14 Boston schools — English, Latin, Tech, Trade, Roxbury Memorial, Dorchester, South Boston, East Boston, Hyde Park, Jamaica Plain, Roslindale, Charlestown, Brighton, and Boston College High — practiced together at White Stadium under the direction of four coaches, and competed for their schools during meets. By 1957, track surpassed baseball as Boston’s No. 1 spring sport for boys. Some 1,000 girls participated in intramural spring track.

They had weekly meets, field on Tuesdays and running on Wednesdays and Thursdays. Before White Stadium, they had one meet a year.

It was high time. But times were changing.

Advertisement

Violence begins

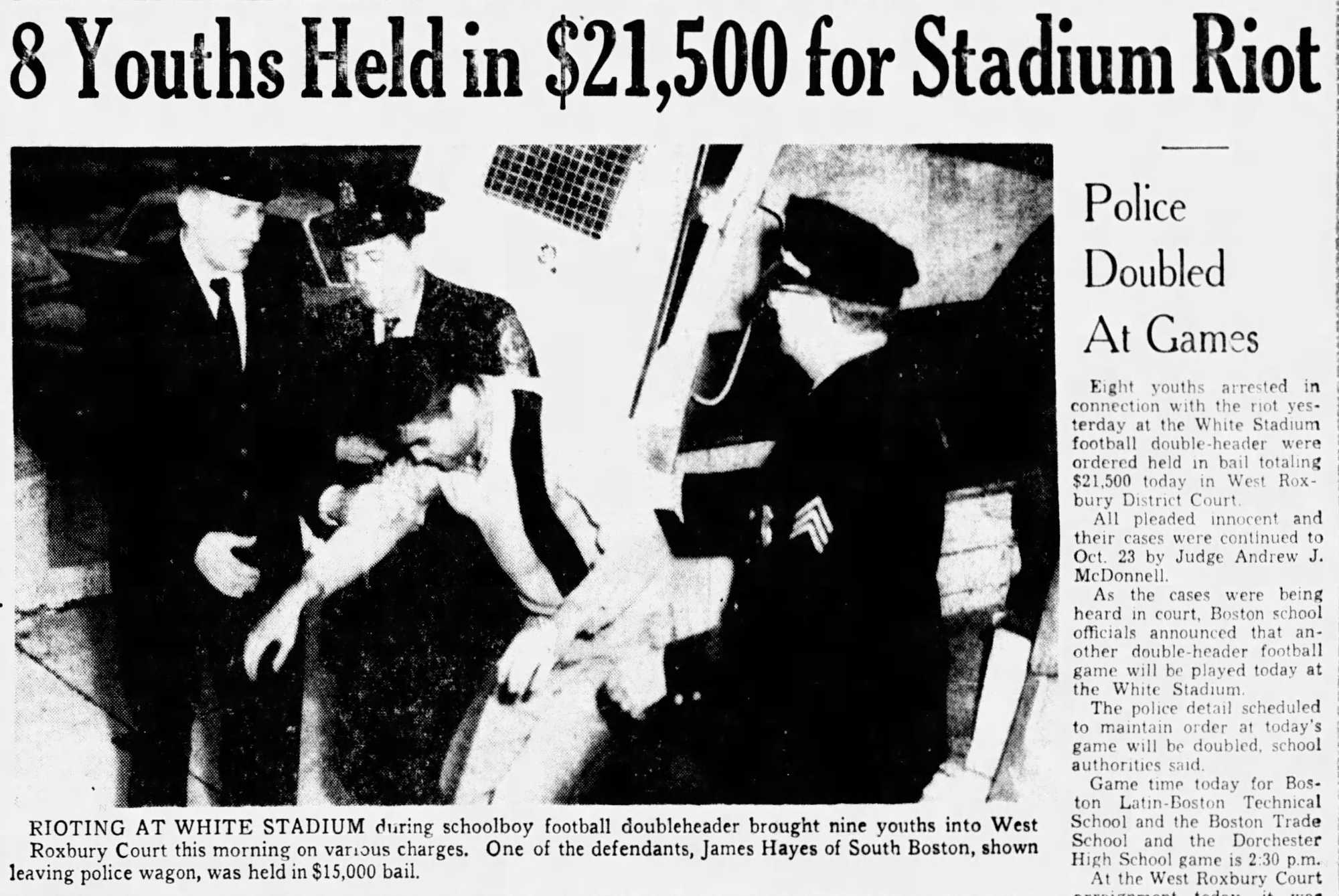

On Sept. 24, 1958, two boys were stabbed after a football game. Two weeks later, schools superintendent Dennis C. Haley declared there would be no more Friday night games at White Stadium. The ban lasted until 2004.

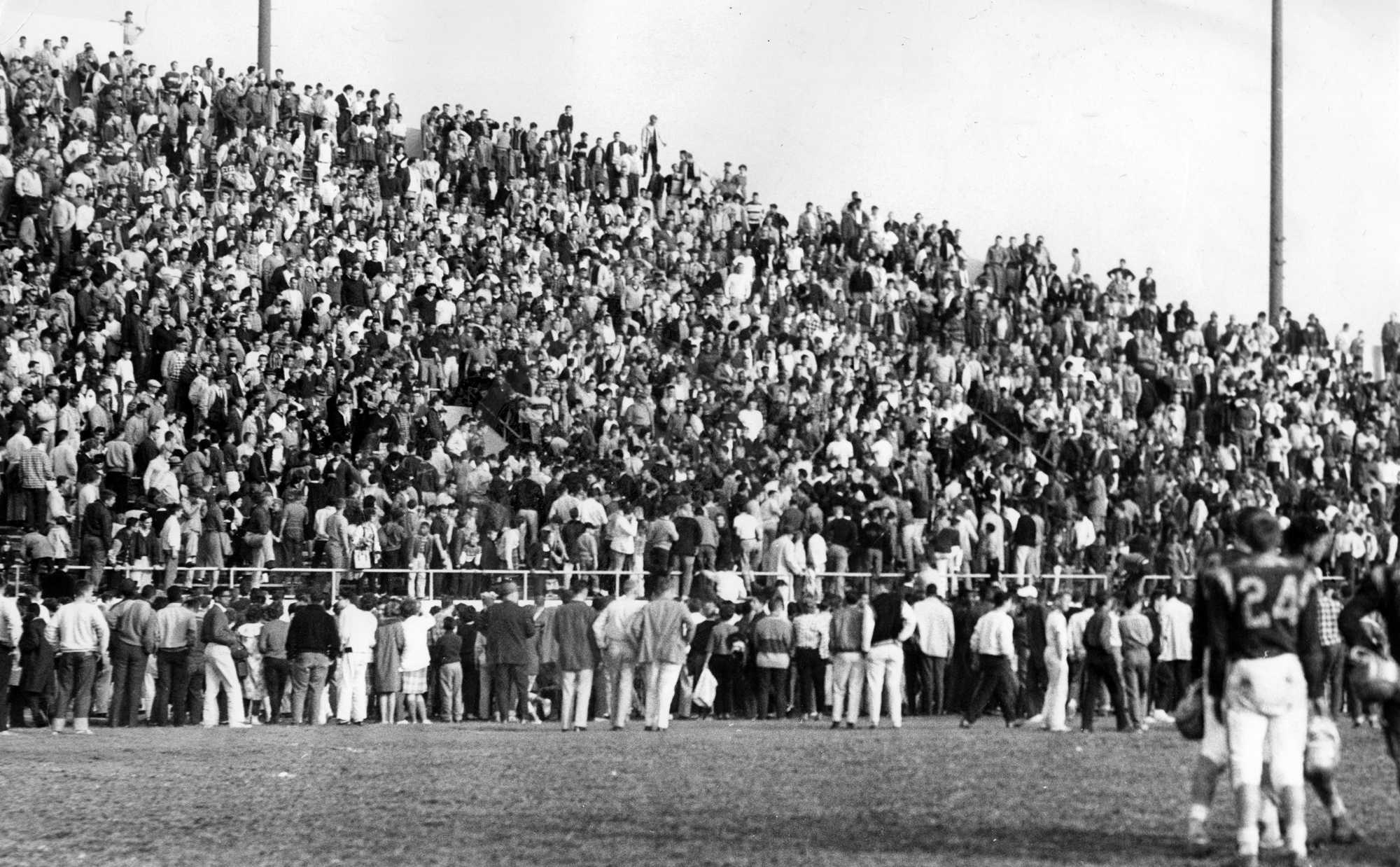

Still, for years, brawls and riots happened semi-regularly. One of the worst occurred on Oct. 12, 1961.

Two boys were critically stabbed, 20 others were hospitalized, and scores were hurt during a race riot between 250 white and Black students during a doubleheader between English-BC High and Charlestown-South Boston.

Officials and players look to the stands at White Stadium on Oct. 12, 1961, as violence breaks out. (Boston Globe Archive)

Fall 1961

Less than 15 years after White Stadium opened, it became a hub for the community — the good and the bad. In 1958, Boston Public Schools superintendent Dennis C. Haley banned Friday night games after two boys were stabbed. The violence reached an apex three years later with an incident the Globe called a “race riot.”

Oct. 12, 1961

Two boys were stabbed and 20 people were hospitalized after a riot at White Stadium. Teenage gangs terrorized the area for hours afterward. Police said it had no connection to a game, and that it started when a Black boy attempted to protect his girlfriend from insults from a white man. Young men above high school age were deemed the main instigators.

Oct. 14, 1961

The Globe wrote in an editorial two days after violence that the City of Boston must act, portending what would come 15 years later with the busing crisis: “A far more dangerous time-bomb now hanging over Boston may explode.” The city boosted police presence at White Stadium going forward.

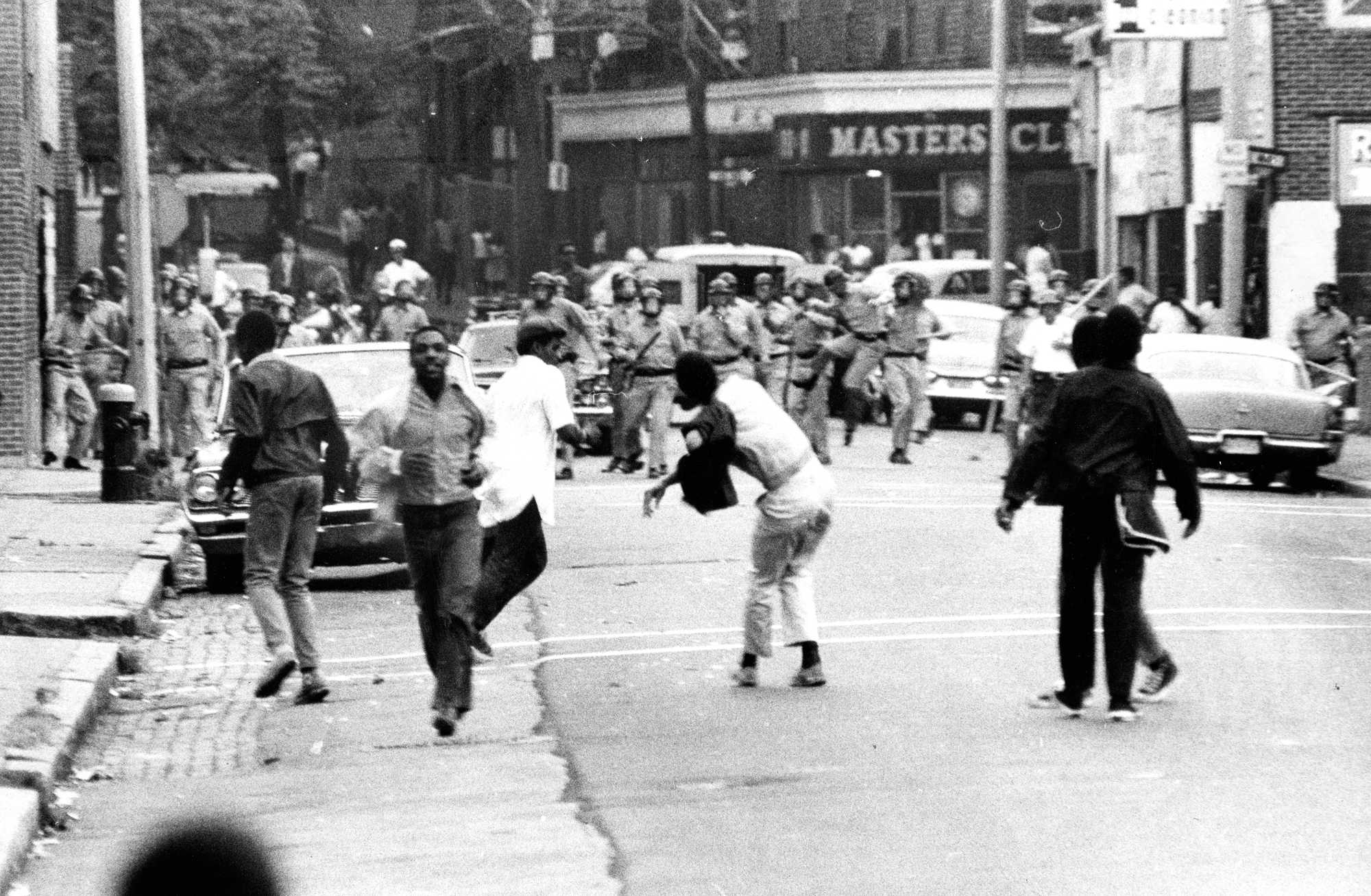

In June 1967, the state track meet was postponed by three days of violence in Roxbury. Rioters smashed some 15 blocks of Blue Hill Avenue and caused hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage from Grove Hall to the South End. More than 75 people were injured and 60 arrested.

Black leaders blamed police for the riot, which reportedly started with a sit-in of Roxbury mothers demanding changes to the city’s welfare program.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, leading to nationwide unrest. With Boston’s fury bubbling, White Stadium hosted several ceremonies to mourn King.

That September, safety concerns postponed, canceled or moved a week’s worth of games at White Stadium. Franklin Park was a central spot of protest, as was the stadium.

Police took over White Stadium in early June 1967, forcing the city to postpone the state track meet. (Ollie Noonan Jr./Globe Staff)

June 3-5, 1967

The state track meet was postponed by three days of violence in Roxbury. White Stadium was used as a staging area for police. “Not since the stadium opened,” the Globe wrote, “has there been such a bleak day.” Later that month, civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael led a rally from Carter Playground on Columbus Avenue to White Stadium. He told a peaceful crowd there that property rights in America “mean more than human rights,” and that Black Americans wanted “in on the profits, not the handouts.”

April 1968

White Stadium hosted several ceremonies to mourn Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., killed in Memphis on April 4. At one, the American flag was taken down, and an Afro-American flag of brotherhood was raised in its place. At another, demands from one section of the Black community for all-Black personnel at schools, police stations, and for Black-owned businesses and Black contractors.

Sept. 26, 1968

More unrest postponed, canceled or moved a week’s worth of games at White Stadium, as Franklin Park was a central spot of protest. The canceled activities included the first soccer planned for the stadium: a halftime exhibition between the newly formed English and Tech teams.

April 1969

White Stadium falls into decline, with the parking lot littered in trash. That summer, the indefatigable Elma Lewis was determined to clean up Franklin Park. “This is Boston’s major park,” she said. “It is Boston’s Central Park. How can we abandon it because it is in this neighborhood?”

Around this time, Boston coaches began noting the lopsidedness between Boston’s teams and suburban teams, which had risen amid white flight out of the city. City schools were suffering from long travel, poor facilities, and low numbers. White Stadium was starting to show its age.

But the pros were interested. Harvard kept saying no to Patriots owner Billy Sullivan, who was looking for a home for his young team, so he turned his attention to White Stadium. In 1970, the Boston Redevelopment Authority proposed an overhaul: It could be enlarged to 50,000 seats for less than $5 million. It would be a mix of public and private financing, the Patriots leasing it from the city.

The stadium, 20 years old, would receive an Astroturfing, so “the schoolboys, colleges, and pros” could use the stadium without fearing the surface’s ruin. Schools would have access Monday through Friday during the football season, and colleges would have it Saturday. The Patriots would play their seven home games on Sunday.

Again … sound familiar?

It was billed as a win-win: “the greatest schoolboy facility in the country,” and the Patriots would stay in the heart of Boston.

Lawmakers stalled. The Patriots wound up in Foxborough.

The city — and its sports — fractures

The 1974 busing crisis canceled the Southie-Eastie game — Southie players boycotted classes — leaving White Stadium without a Thanksgiving Day game for the first time since its opening in 1949.

The following year, city football was fractured and decimated by the chaos, punctured by a rock-and-knife fight that injured four and required 100 police officers to end it.

The Boston teams mostly played suburban teams with more coaches, better resources, newer equipment, and playing fields. Teams played in front of just hundreds.

“Mothers tell their kids, ‘Don’t go to White Stadium,’ ” city councilor Larry DiCara said at the time.

It had become “a battleground for white and Black schoolboys in the city,” said Rep. Ray Flynn, who at the time represented South Boston.

The Eastie-Southie Thanksgiving game was moved to Boston University’s Nickerson Field. Southie and Charlestown stopped playing at White Stadium after just 84 fans showed up.

In front of a crowd of 30,000 on July 7, 1974, The Hues Corporation — most famous for their single "Rock the Boat" — perform at White Stadium. (Bill Curtis/Globe Staff)

Summer 1974

Uptown in the Park, a three-part series of concerts to benefit the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts, brings major acts to White Stadium. On July 7, 30,000 watched Sly and the Family Stone along with Tower of Power, Hues Corporation, Donald Byrd and the Blackbyrds, as well as Richard Pryor. On Aug. 25, 25,000 saw Funkadelic along with The Voices of East Harlem, The Isley Brothers, Gil Scott-Heron, Mandrill, and the Bar-Kays.

October 1974

The busing crisis throws the city into disarray. White Stadium is nearly empty during games. “It’s crazy,” Leigh Montville wrote from the stands. “The schools are in turmoil and everybody is afraid and you sit in the sunshine and watch football and nobody else is there. It is a strange, sad feeling.”

October 1975

There are as many police as spectators at some games. The city league is gone. At White Stadium, “the buses are lined up next to the end zone now, and five police motorcycles are parked at midfield … Administrators shrug in dismay.” An Oct. 24 game between Southie and Dorchester is marred by rock-and-fist fights between Black and white spectators, four people injured, 100 officers needed to stop it. More fights occurred the next day at Southie High, closing the school for the day. Fifteen students were arrested.

The worst of the racial violence came in September 1979, not at White Stadium but at Charlestown High, when Darryl Williams was shot by a rooftop sniper and paralyzed during a game. The 15-year-old wide receiver would spend the rest of his life as a quadriplegic and died in 2010 at the age of 46. He was a Roxbury resident assigned to Jamaica Plain High, playing for an all-Black team. Charlestown did not play another home game for nine years.

Sixteen-year-old Darryl Williams (right) was shot by a rooftop sniper during a game at Charlestown High in September 1979. He was paralyzed from the neck down. Days later, on Oct. 3, Boston's deputy mayor Clarence "Jeep" Jones addressed the hundreds of students who walked out of class in protest. (Left: Joe Dennehy/Globe Staff, right: Stan Grossfeld/Globe Staff)

In 1980s, the Globe chronicled the bleak state of city football. White Stadium went unpainted, and half the lights didn’t work. The city athletics budget left enough to buy grass seed and fertilizer, and little else. So few people were attending games that the city stopped charging admission — it would lose money paying the ticket-takers.

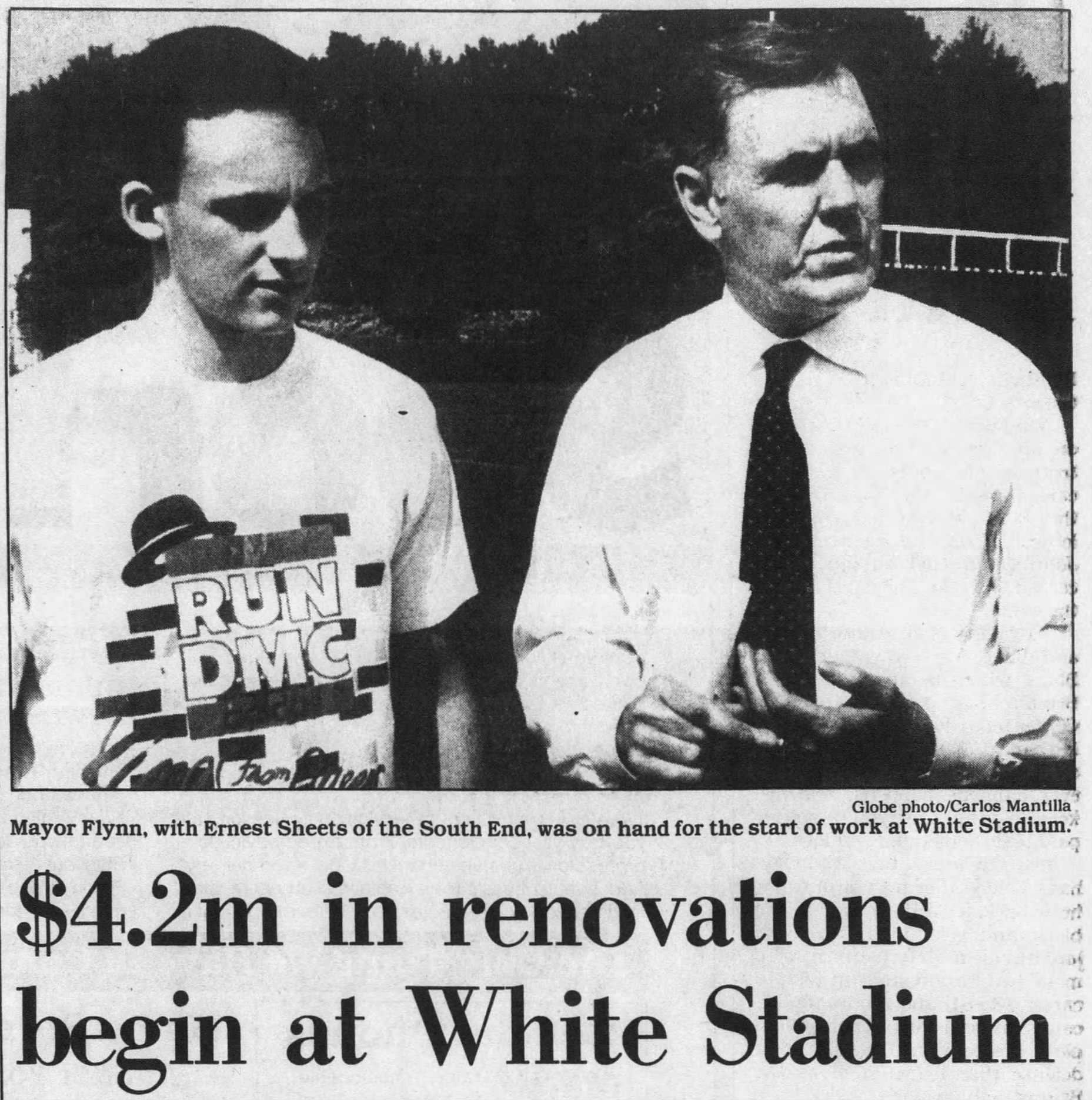

In 1984, Flynn, the newly elected mayor, planned between $2 million and $3 million in renovations for the shoddy stadium.

“The scoreboard is broken, a victim of vandalism; time is kept by an official on the field,” wrote the Globe’s Marvin Pave. “Benches are rotted and some are missing. Paint peels from the sideline walls. Most locker facilities — showers, toilets and water coolers — don’t work.”

A bill to provide necessary funding sat on Beacon Hill for more than two years. The project was scaled down. Sound familiar?

Finally, some progress

The wooden bleachers at White Stadium are shown broken in July 1986. In the early 1980s, the city planned between $2 million and $3 million in renovations for the stadium but progress took nearly a decade. (George Rizer/Globe Staff)

1988

Bids go out for renovations. The plans for athletics department headquarters and a trainer’s room are scrapped, but the city hopes to get a grass field, a track, and new stands. “People wonder why the Boston schools are so bad. The White Stadium project has been in the works for five years and there is still no guarantee anything will ever happen,” the Globe wrote.

Sept. 8, 1989

Mayor Flynn holds a groundbreaking at 40-year-old White Stadium as $4.2 million in renovations begin. Due up: a six-lane rubber track, replacing the six-lane cinder track; aluminum seating, new jumping pits and weight event areas, new goalposts, locker rooms and showers in the West stands, and masonry and paint repair work. The work was expected to take a year.

Sept. 16, 1990

White Stadium reopens as players from various teams pack the grandstands. West Roxbury beat Latin Academy in the first game back.

The renovation was completed in 1990, ushering in a brief era of prosperity.

White Stadium hosted one of its most memorable games ever on Thanksgiving 1991. Both Eastie and Southie were 9-0; a playoff berth was at stake. It held the World Cross-Country Championships the following year — said to be the first world championship to be contested in Boston — and city and state soccer championships.

In 1995, Boston schools AD Rocky DiLorenzo, who worked out of a small office at White Stadium, oversaw what the Globe called “tremendous success” in all city sports — “many areas are on par with suburban schools.”

But the empty seats remained. In 2003, Kenneth Still took over as Boston schools AD, hoping to fill them. “I would like to bring back this,” he said in a Globe story, pointing to an old black-and-white shot of a packed stadium. The 1967 English grad could remember “this whole side of the stadium, I’m talking 500 people here … cheering on a track team, never mind football.”

As Boston’s pro teams entered a golden age in the 2000s, however, its school sports again fell into poor shape, wrote Bob Hohler of the Globe.

Even on a beautiful, 60-degree fall Friday afternoon, noted Paul Duhaime, Burke assistant football coach, “you turn around and there are only 10 people there.”

The O'Bryant sideline rejoices during a second-half play in its win over South Boston Education Complex in the first Friday night game at White Stadium in decades. (Bill Greene/Globe Staff)

Sept. 17, 2004

Friday night high school football returns after 46 years. A brawl in Egleston Square in 1958 after an exhibition game at the stadium led city officials to ban Friday night games with a few exceptions. O’Bryant in Roxbury beat South Boston Education Complex.

June 2009

A Globe series by Bob Hohler explores the pitiful state of Boston school sports. The athletic departments are chronically underfunded and overwhelmed. Mayor Thomas M. Menino, in response, says he will create a charitable nonprofit spearheaded by former athletes and business leaders. The plan set a $4 million goal over 18 months.

2013-15

In June 2013, Suffolk Construction head John Fish unveiled a $45 million plan to turn White Stadium into a year-round athletic and academic hub. By spring 2015, the plan is shelved by Mayor Marty Walsh — another public-private partnership unfulfilled.

Fall 2021

Scholar Athletes, a program created by John Fish in the wake of the Globe’s 2009 series, quietly shuts down. Fish cites the COVID-19 pandemic. “I’m shocked because I thought the program was soaring,” said Cassandra Teneus, one of its early beneficiaries as an All-Star basketball and volleyball player at Jeremiah Burke High School in Dorchester, where she graduated at the top of her class in 2013. “I’m super grateful that Scholar Athletes was part of my life, and I’m very sad that it won’t be there to give future students the kind of hope and help that we all received.”

After the Globe’s Bob Hohler in 2009 reported an award-winning, multi-part series on the many issues plaguing Boston high school sports, the political winds blew favorably for White Stadium for the first time in decades.

Mayor Thomas M. Menino had a plan for a Northeastern University-funded overhaul in 2009 that would have Northeastern’s football team play its home games there. That didn’t happen; Northeastern dropped football that fall.

TechBoston players leave the locker room at White Stadium for a game against Chelsea in November 2023. (Barry Chin/Globe Staff)

In 2013, Suffolk Construction head John Fish — before diving headlong into the failed Boston Olympics 2024 effort — unveiled a $45 million plan to turn White Stadium into a year-round athletic and academic hub.

But as weeds were growing through the track surface, Mayor Marty Walsh in 2015 shelved that renovation and expansion plan, citing budget concerns. Another public-private partnership went unfulfilled.

But then in 2022, Boston Unity Soccer Partners, an all-female investment group, launched a bid to bring the NWSL to Boston. White Stadium was their top choice for a venue.

A fresh start

Generations of people in Avery Esdaile’s position have had to make excuses for White Stadium’s condition. No longer — at least for now.

“We were doing the best with what we have,” said Esdaile, the city’s athletics director since 2014. “Now we’re stepping into a facility where we won’t have the same concerns.”

He doesn’t doubt that BPS athletes will have a year-round space to train, compete, and grow. The historic architecture will remain, but refreshed. The women’s soccer team will create energy for fans and opportunities for city residents.

“It’s a connector,” Esdaile said. “When you have that space that’s so unique, different generations in a city, that’s something we should be proud of and use moving forward. We want people to have experiences in there that they’ll talk about throughout their lives.”

What will White Stadium mean for future generations of Boston school athletes?

“I hope it’s a starting point, a springboard, an incubator, an igniter,” Esdaile said, “for a city that embraces youth sports, and that we’re seeing kids out participating and playing.

“We’re excited. We’re happy. We’ll be great stewards. But we shouldn’t forget the history.”

Demolition was underway at the White Stadium site in August. (Danielle Parhizkaran/Globe Staff)

Credits

- Reporter: Matt Porter

- Editors: Katie McInerney

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and Colby Cotter

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Andrew Nguyen

- Copy editor: Robert Fedas

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC