The promise unkept: How Congress failed America’s disabled students

Jen Fowler comforted her son Dante, 12, during an episode at their home in Wakefield in February. Jen refers to 2 p.m. as the “bewitching hour” when Dante’s outbursts begin.

WAKEFIELD — It was 10 a.m. on a Wednesday, and Dante Fowler was seated in his family’s living room for “circle time,” the official start to his school day. A children’s song chirruped from a nearby speaker: “Good morning! (Good morning!) How are you? (Just fine!).”

Dante, a 12-year old with cropped brown hair and pale skin, stared listlessly across the room, his 78-pound body swallowed by the folds of a plush gray sofa. His mother sat at his side, filling in as a makeshift teacher. She sang along with the song, longing with every note to resuscitate her once bright-eyed boy.

By this January day, more than a year had passed since Dante had been allowed to go to school with other kids. His local school said it could not educate him, because of his severe autism. Left to wait for a school to come along that would, Dante was all but educationally abandoned.

Circle time, emulating the structured carpet activity in grade school, had become part of his mother’s attempt to give her boy some semblance of a normal school day routine. But it only underscored Dante’s isolation: The solitary boy, a circle of one.

Dante, who uses a tablet to speak, finally responded to the song: “I feel,” he paused, with shoulders slumped, steel blue eyes downcast, “broken.”

The tune trilled on.

“Now that we’re together, learning‘s so much fun. The more of us the better, so come on everyone!”

Every day in the United States, disabled children like Dante are being cheated out of an education, relegated to their homes for months on end because no schools will serve them, an investigation by the Globe’s Great Divide team has found.

Their public school districts have given up on teaching them, pledging instead to pay for them to attend schools elsewhere that offer more intensive support. But other options, which often include highly sought after private schools, can be near impossible to come by, leaving kids in the lurch for extensive periods of time.

Dante Fowler, 12, peered over the gate while his mother, Jen, served dinner to his brothers, at their home in Wakefield in February. To ensure his safety, Dante is confined to the living room and the bedroom he shares with his twin brother, Nino. Jen said feels guilty she never gets to sit and eat dinner with her other children.

There is no consistent way to count these children in such educational limbo; in many cases, they are still enrolled as full-time district students as they await new placements. But they are out there, according to the Globe’s reporting, in cities and small towns, in red and blue states, some shut out of school for months, others for years — their parents frequently forced to give up their jobs to become caretakers.

The Globe spoke with more than two dozen parents across Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, Virginia, Oklahoma, and New Mexico for this story. Each described in detail the painful consequences of their child‘s prolonged isolation. Starved of school, the children deteriorated into shells of their former selves.

Part of what’s driving the crisis is a supply-and-demand problem that has devastating and far-reaching effects, not just on disabled students and their families, but on entire school communities. The population of students with complex disabilities, including autism, has grown in recent years, but there are nowhere near enough trained special educators to meet the children’s needs, experts said. What’s worse, experts and advocates argue, is the lack of urgency to fix the problem. In a world replete with disasters, disabled children like Dante are often forgotten.

“It is a tragedy,” said Arlene Kanter, founder of the nation’s first disability law program, at Syracuse University in New York.

“It’s a system that is broken.”

Registered behavioral technician Mackenzie Ansin (right) steadied Dante as he jumped on a trampoline at his home in January. The pair were taking a break from learning exercises. The Fowlers' living room serves both as a classroom and gymnasium.

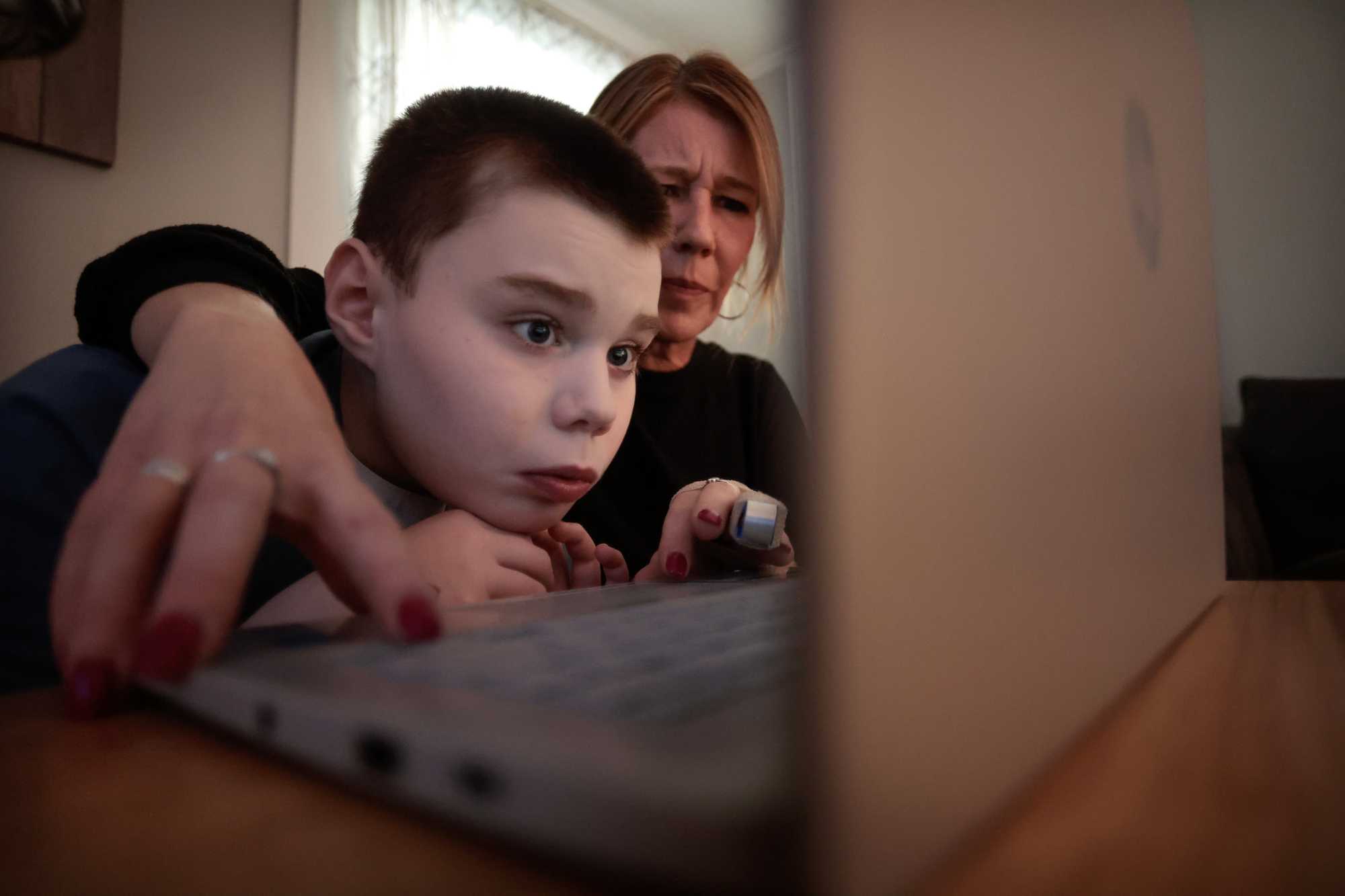

Jennifer Fowler helped her son Dante during his virtual, “morning meeting” at their home in Wakefield. Jen compared the “morning meeting” to the “circle time” he would have at school, when they discuss weather, emotions, the date, and day of week.

Jennifer Fowler (right) asked her son how he’s feeling, and he responded with a card that reads “scared,” during his “morning meeting” at their home.

Advertisement

Fifty years ago, the nation made a pledge: No child, no matter how complex their disability, would be deprived an education.

It was a sea change in American schooling. For decades, disabled students had been warehoused in school basements and state institutions, or left to languish in their homes. Under the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act (known today as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act), public schools for the first time were legally bound to educate these children, providing instruction and therapies to meet their individual needs. Robust federal funding was promised.

Not once in all these decades has Congress lived up to its end of the bargain, a promise to cover 40 percent of the extra cost needed to educate children with disabilities. Today, the US government contributes a mere 10 percent of the cost — just a quarter of its 1975 commitment.

There’s not a community in the US that isn’t grappling with the tangled web of consequences bred by this shortchanging: Larger class sizes. Teacher burnout. Cuts to other school programs. Local tax hikes.

And then there are kids like Dante, who, by no fault of their own, fall victim to a system too strapped to meet their needs.

To be sure, millions of disabled children have been helped by the 1975 law, benefitting from specialized education they otherwise wouldn’t have received. But there is much room to improve, experts and advocates agree.

With more qualified staff, schools would be better equipped to serve children with complex disabilities. Their general education peers would benefit from calmer, safer classrooms and more teacher attention.

Frustrated, Jen Fowler listened during a virtual meeting regarding Dante’s transition back to school, at her home in Wakefield in February. Jen was stressed that her son had been out of school for 16 months. She questioned, “Why is this taking so long?”

Research shows students with excessive absences perform worse than their regularly attending peers in math and reading. Those who miss more than 10 percent of school days are significantly less likely to graduate on time.

Advocates said more federal funding could keep these children in school.

This fiscal year, Congress appropriated $14.4 billion toward the education of 7.9 million disabled students — a commitment far short of its obligation. To meet its 40 percent pledge, it would need to allocate $31 billion more. (For perspective, federal funding for the Department of Defense this fiscal year was nearly $900 billion.)

Closing the gap could support more than 400,000 additional special education teachers and specialists nationwide, according to a budget note written under the Biden administration.

With President Trump focused on slashing federal funds, it seems unlikely that Congress will allocate $31 billion more to special education in the near future.

But there is a solution on the table, a 10-year “glide path” approach, giving the federal government a full decade to reach its share of 40 percent. It’s a cause that has united strange bedfellows: The nation’s largest teachers unions support full funding, as do a number of Republicans.

Critics of boosted funding, however, argue too much of Congress’ current appropriation is going to a bloated bureaucracy, rather than directly benefiting kids.

Advocates say that argument misses the point.

As one staffer for Republican Congressman Glenn “GT” Thompson put it during a February briefing on the matter: “This is not throwing money at an issue. This is something Congress committed to 50 years ago and has never done.”

Confined to his family’s two-bedroom apartment, Dante over time crumpled into a husk of his former self, said his mother, Jen Fowler.

Dante — the baby of the family, a mama’s boy from the start — had always been generous with his nuzzles; in time, such affection grew rare, Fowler said. Dante still found comfort in SpongeBob and Dora, and sensory relief while in the shower, hot water pelting his skin, dance music cranked to full blast. But sightings of the slight gap in his two front teeth became scarce, his lips rarely parting in smile.

Without school-based field trips and friendships, Dante had little to look forward to. Hemmed in his family’s living room by baby gates, Dante took his frustration out on his limited surroundings, tearing down photographs and decorations one at a time until the walls were bare. Somewhere along the way he’d lost his ability to chew, so he ate yogurt for breakfast, yogurt for lunch, and yogurt for dinner. Over time, Dante glued himself to his family’s sofa, overwhelmed by apathy.

Dante affectionately touched foreheads with his mother at their home in Wakefield in February. He had calmed down after an episode earlier in the day.

“Our fun-loving kid that used to smile all the time and look forward to everything ... just wants to sit in the house and lay down on the couch all day,” Fowler said in February, 16 months into her son’s isolation.

Dante is one of nearly 1 million students nationwide eligible for special education due to their autism. He requires extra support to be successful at school. Like many children with more severe autism, he cannot express himself verbally.

That often leaves the sixth grader — who can understand what those around him are saying — visibly frustrated. At its most extreme, that frustration can manifest in aggression and self-injurious behaviors. Other times, he may smear his own feces on his surroundings. (Many autistic children experience gastrointestinal issues.)

It was for those reasons Dante’s suburban Boston school district, Wakefield Public Schools, said in September 2023 it could no longer educate him.

“It was clear Student required greater support than the District was able to offer,” Wakefield’s director of special education wrote in an April 2024 letter to the state, after Fowler submitted a formal complaint against the district.

The district agreed to pay tuition for Dante, then 11, to attend school elsewhere, as is required under federal special education law. But months slipped by with no school, public or private, willing to take him. Some said they weren’t appropriate for Dante’s significant needs. Others said there was simply no spot for him.

Fowler has repeatedly sought help from Wakefield Public Schools to no avail. Legal documentation viewed by the Globe shows Wakefield did not provide him any educational services as he awaited a school placement, such as tutoring in his home by a special education teacher.

Wakefield said it couldn’t find a teacher available, Fowler said.

The district did not return multiple requests for comment about this story.

Fowler, who spent her own money on educational materials, said she has done her best to teach Dante. Yet she knows her limitations. She does not have the training her son needs.

Stuck at home, Dante continued to lose his spelling and counting skills.

Jen Fowler restrained Dante during an episode at their home in Wakefield in February, his 16th month without school. Jen refers to 2 p.m. as the “bewitching hour” when Dante’s episodes begin.

Phil Corriveau rested in a beanbag chair waiting for Dante to fall asleep at their home in Wakefield in February. Dante's mother, Jen, said her son will not fall asleep if he is left alone. Phil often falls asleep himself while waiting.

Advertisement

The challenge of educating children with disabilities is not new.

A generation of Americans first confronted video of the deplorable treatment of disabled students in 1972, when journalist Geraldo Rivera’s expose on the Willowbrook State School on Staten Island aired on TV. Rivera’s reports showed emaciated children living in squalor and given no education.

By the end of that year, Massachusetts passed the first law in the nation guaranteeing disabled students a right to an education. That law, known today as Chapter 766, served as a model for the national version passed three years later.

The federal law required local school districts to ensure children with even the most challenging disabilities, be it medical or behavioral, were provided an education. If districts could not do so on their own, they would be mandated to pay for a student to attend school elsewhere. In the Northeast, specialized private schools cropped up to meet districts’ needs, many of which still operate today.

In many areas elsewhere in the country, especially in rural communities, such infrastructure was never even established.

In Los Lunas, N.M., for example, there is no private special education school nearby to which Christy Schneider can enroll her son, a boy with Angelman syndrome, a rare genetic condition that causes physical and intellectual disabilities. Meanwhile, his local district has failed to appropriately support him, Schneider said.

“My son was 10 last time he went to school,” she said. “He’s 18.”

In Connecticut, Anne Distassio said her 7-year-old son who is autistic and spent seven months waiting for a school was left with “mental scarring” from the ordeal.

“It’s not fun when you feel like no school wants you,” she said.

In Oklahoma, Amber Boyer’s son was forced out of his public school district at 15 because of behaviors he couldn’t control due to his autism. Davin spent roughly nine months in 2023 at home awaiting a new school. His behavior deteriorated rapidly. He hit Boyer, pulled her hair, and cracked her ribs. He also released his frustration on the family’s home.

“We had the windows boarded up,” Boyer said. “He was just breaking everything.”

When Davin finally received a placement, it was at a psychiatric facility in rural Kansas three and a half hours from the Boyers’ home. In late 2024, he was shuffled to a new placement in Kansas City. This past March, Boyer withdrew her son from the school after he was abused by a staff member, she said.

Most recently, Davin was denied acceptance to a Texas school, which said it couldn’t accommodate his needs. He is back at home, waiting again.

Dante Fowler was pushed on a swing by Phil Corriveau at Sturges Park in Reading in March. Phil says Dante loves the swing and could stay here all day. Phil met Dante when the boy was 5, and said, "When I first met Dante, I was in awe of him, I was amazed. I thought, 'What is he thinking?'"

Phil Corriveau welcomed Dante home from school with a big hug and a spin at their home in Wakefield in April. Dante was arriving home from the Amego School, which specializes in teaching students with autism.

The Boyers live in Newkirk, a one-stoplight town of about 2,000. Amber Boyer wishes her son could receive the support he needs within his own community, but knowing the school district’s finances, she doesn’t see how.

The district receives about $175,000 annually in federal special education funding — not nearly enough to stand up its own program for children with severe autism, while also attending to other disabled students’ needs.

In the absence of comprehensive federal funding, districts across the country are largely forced to rely on local revenue to meet their legally binding special education obligations, such as providing a student with a 1-to-1 aide or arranging special transportation for a disabled student to and from school.

The consequences of this ripple across classrooms and communities. Districts, for example, may need to tap into funds that otherwise could be allocated toward smaller class sizes or art and music teachers. Special education expenses, districts increasingly say, are among the reasons they can’t give teachers raises or why local tax hikes are necessary — both frequent occurrences in Massachusetts in recent years.

Disabled children and their parents are often the ones saddled with blame by their neighbors.

“Everyone you talk to will say that they are empathetic towards the child. They’re empathetic towards the family. Everybody will say things like, ‘By the grace of God, that’s not my situation,’” said Brian Gruber, a Maryland-based special education attorney. “Behind closed doors, everybody says, ‘I think it’s unfair my kid — my smart kid — is not getting the smaller class or the more challenging or more rich curriculum, because all the money spent on that kid with a disability.’”

Jen Fowler sat with Dante at their home in Wakefield in March. Jen worries about Dante’s isolation. She said, “He’s bored, he’s depressed, he’s definitely regressing. He doesn’t know how to interact with his peers. Now he has anxiety. He used to be in a classroom, on a bus. How do you go from that to this?”

In Wakefield, needing to take care of her son 24/7, Fowler had to give up her job working with disabled adults. The financial strain on her family has been punishing; if it weren’t for her partner’s salary as an electrician, Fowler said, she doesn’t know how she’d be able to support Dante and his two brothers.

Most of all, she’s felt helpless, unable to save her son from hurt.

There was the back-to-school shopping trip for his brothers last August, when Dante, then in his 10th month at home, picked out his own backpack, only for it to sit empty and unused. Then came his 12th birthday in October, no classmates for him to celebrate with. At some point, he stopped interacting with his brothers, one of whom is his twin.

He once loved playing games at Dave and Busters or shopping with Fowler at TJMaxx. But after so much isolation, his social anxiety skyrocketed. Things came to a head this past winter in a grocery store. While trying to soothe Dante’s agitation, Fowler got her finger stuck in the wiring of a shopping cart and it fractured.

Fowler could no longer safely take Dante on outings.

Yet even in the comfort of his own home, Dante’s behavior continued to decline. Just days after the grocery store outing, Fowler, in what had become an increasingly frequent occurrence, found herself needing to physically restrain Dante to keep him from hurting himself.

As he sprawled on his bed, flailing his limbs and crying in distress, Fowler lay on top of him like a weighted blanket. After several minutes of her applying pressure, Dante calmed, finally able to rest on his Pokemon sheets.

Fowler, a slim woman with a voice rough as gravel, often wonders how Dante will be affected by his isolation in the long run — what damage may be repaired, and what will remain permanent.

Like many special education parents, Fowler eventually decided she would need to involve an attorney to spur Wakefield Public Schools into action. She found one to represent her pro bono. Finally, in March, Dante’s 17th month at home, the district came forth with a proposal. It left Fowler stunned.

Jen Fowler and her partner, Phil Corriveau, gave Dante a haircut at their home in Wakefield in March. "It took a while to desensitize him. Eventually, he didn’t cry. Now I think he likes it. He wants to wear the cape,“ Jen said.

Jen Fowler headed back to the house as her son Dante departed on a school bus outside their home in Wakefield in April. The bus would transport Dante to his first day at the Amego School in Franklin.

For months, Dante had been receiving in-home behavioral therapy for 30 hours per week. The therapists, employed by a company Fowler found and paid for through her insurance, had developed strong relationships with the boy.

The district, citing difficulties in finding its own behavior therapists, demanded Fowler give up her arrangement. The therapists who had been working with Dante, officials proposed, would become contractors for the district. But instead of the 30 hours per week Fowler’s insurance had been covering, the district said in a proposed contract it would pay for just 10 hours.

Advertisement

The Fowlers’ experience highlights one of the biggest consequences of federal underfunding: staff shortages.

The problem isn’t that college graduates don’t want to become special educators — it’s that they don’t stay. (Data compiled by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education found the number of special education bachelor’s and master’s degrees conferred from 2010 to 2023 were actually up 7 and 9 percent, respectively.)

Special education teachers and therapists typically aren’t paid enough for the training they’re expected to have or for the demands put on them. In addition to the instructional responsibilities of a general education teacher, special educators face the added pressure of legal compliance, spending extra hours on mandated paperwork and meetings. Burned out, they leave for less punishing jobs with equal or greater pay — a trend accelerated by the pandemic.

In 2021, Bryson Evans, a Durham, N.C., special education teacher, left traditional teaching after nearly 20 years in the classroom for a job supporting students with disabilities on long-term hospital stays. If her district had money to hire more teachers and support personnel, the job would have been more sustainable, she said.

“It was really overwhelming to try to keep up with the paperwork and the lesson planning and the actual instruction, just with so few hands on deck,” she said.

Advocates for full funding of special education said an increased federal investment is critical to getting more classrooms fully staffed.

There have been two glide path bills filed in Congress this year, including one in the House boasting a number of Republican cosponsors.

A spokesperson for the US Department of Education did not answer the Globe’s questions about President Trump’s position on the full funding of special education, but noted in a statement that his budget does not make any cuts to special education funding and said the administration “recognizes that the one-size-fits-all education system simply isn’t working — especially for American families and students with disabilities."

Dante Fowler ran back to class with speech pathologist Marley Dutcher after a break on the playground at the Amego School in Franklin in April. After completing a series of lessons Dante is rewarded with a recreational period.

Case coordinator Kelsey Sundin (left) and behavioral therapist Mackenzie Burke worked to calm Dante during an outburst at the Amego School in Franklin in April.

One early April morning, Fowler was up before dawn, scurrying about the apartment.

The backpack Dante had so excitedly chosen for himself those many months ago sat on the kitchen counter ready to be used for the first time. Fowler tucked spare changes of clothes inside. On the refrigerator’s dry erase calendar, she had written a note marking this moment, one she was starting to think would never come: ”Dante’s first day of school!!!"

Finally, after 17 months at home, the Fowlers had received good news: The Amego School, which specializes in serving children with autism and other developmental disabilities, had an opening. The school saved the spot for Dante.

It wouldn’t be easy. The commute to the Franklin-based school would take an hour and a half each way. Still, Fowler felt she could finally breathe.

“I thought we were ending the story without a happy ending,” she said. “I truly did.”

On this morning, Dante, dressed in blue jeans and a long sleeved Abercrombie & Fitch T-shirt, spun in a circle as Fowler’s partner, Phil Corriveau, spritzed him in cologne.

And when Fowler tied the laces on Dante’s new Adidas sneakers, bruised shins peeked out from beneath his jeans — the injuries, self-inflicted, a reminder of all he had endured.

At 7:15, Fowler and Dante walked hand-in-hand to the sidewalk, where she helped buckle him into the backseat of a waiting van. Sloppy snowflakes, too wet this time of year to maintain a crisp pattern, soaked into Fowler’s hair as she waved her boy away.

A school staff member would later tell Fowler over the phone that Dante was covered in his own feces by the time he arrived at Amego. For the staff there, though, it was no big deal. They helped him shower. He put on a fresh set of clothes. And off to class he went.

When Dante arrived back home at the end of the day, he was all smiles and cuddles and kisses — a Dante his family hadn’t seen in months. Proud of himself, Dante used his tablet to summarize his day: “Good job school,” he said, his tooth gap on full display.

After all they’d been through, though, Fowler couldn’t help but feel anxious still. She knew from experience that one good day could be followed by dozens of bad ones. What if Dante, after all his time in isolation, proved too difficult to educate?

Other families, she knew, would be waiting to take his spot.

Other children, she knew, just as deserving as Dante.

The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide. Sign up to receive our newsletter, and send ideas and tips to [email protected].

Dante watched his mother prepare a peanut butter and jelly sandwich when he returned home from school in April. Jen Fowler said Dante is now obsessed with having a peanut butter and jelly sandwich every day when he gets home from school. She cuts it into small pieces and serves it with milk, as he's still working on his ability to chew.

Credits

- Reporter: Mandy McLaren

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Cristina Silva

- Photographer: Craig F. Walker

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Design and development: Daigo Fujiwara-Smith

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Video producers: Olivia Yarvis, Julianne Varacchi

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC