Their brother’s death in the Cape Verdean gang war sparks another violent chapter. When would it end?

A priest prayed over the casket of Luis DoSouto, the murdered chef. The pallbearers wore white. Rain had fallen, and gray morning light filtered through the church’s stained glass windows.

In the pews, mourners wept. Milton DoSouto was inconsolable, rocking back and forth, chanting the name of his older brother, “Luis! Luis!”

Blood on the streets

![A stabbing in Dorchester ignites an all-out war. One family becomes the perpetrators — and the victims.]()

Part 1: A stabbing in Dorchester ignites an all-out war. One family becomes the perpetrators — and the victims.

![Their brother’s death in the Cape Verdean gang war sparks another violent chapter. When would it end?]()

Part 2: Their brother’s death in the Cape Verdean gang war sparks another violent chapter. When would it end?

![‘I don’t want to fight no more’: Members of the Outlaws take stock of the destruction — and seek atonement]()

Part 3: ‘I don’t want to fight no more’: Members of the Outlaws take stock of the destruction — and seek atonement

It was May 2006, five days after Luis was shot outside the DoSouto home in Dorchester. His death was the latest amid the Cape Verdean gang war that had torn apart the community and along with it the DoSouto family. Milton, whose Cape Verdean Outlaws gang was drawn into the war and had become its own engine of violence, had been shot up so badly he could not walk without a cane. Gunfights had erupted outside the family’s door. And now Luis.

None of it made sense, and there was no apparent way to stop it. The city had failed to focus effectively enough on the lethal potential of a dense cluster of warring youth gangs until it was too late.

It was a lesson for the future; there was no time to look for lessons now.

The slaying of triggered more killing — first, the shooting of a young man who lived in enemy territory but had played no role in Luis’s murder. Now some of the Outlaws at his funeral carried guns under their clothes, anticipating a retaliatory strike, the next turn in the unabating cycle of violence.

No one at the funeral realized it yet, but Luis’s murder had set the stage for another deadly chapter of the war, one that would end with another indelible loss for the DoSouto family.

The casket of Luis DoSouto, the oldest of 10 children, was carried from St. Patrick Church in Roxbury after he was shot to death in front of his family's home in 2006. A popular chef, he died at age 25. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

Sixteen-year-old had no interest in gangs. His older brothers had tried to make sure of that. He spent all his free time on the basketball court, dribbling and shooting until he ached. He was good, and getting better.

“The kid could play,” said Steve Drayton, a youth worker and basketball coach hired by the city to address violence in the Cape Verdean community. “When I took him to tournaments, people were talking about, wow, this kid can go places.”

Alex had the makings of a high school star bound to win a college basketball scholarship. Of all the DoSouto kids, he was the one seen with the best shot at making something big of himself.

and had done their best to shield him from the war. had stepped up too. Six years older than Alex and a talented ballplayer himself, Nugget had taken Alex under his wing, coaching him, pushing him. Alex had been happy, outgoing. But that day at the funeral, while others wept, Alex sat rigid and mute, staring ahead stone-faced.

It soon became apparent to his siblings that something terrible had happened inside him.

“Alex was going to be good,” Milton said. “He was going to do his basketball and everything, but Luis’s death crushed him. We all saw the change in Alex then. It was like a light switch went off.”

Of all the DoSouto siblings, Nugget was closest to Alex. They had forged a relationship through the sport they loved. Quiet and a bit of a loner, Nugget believed basketball saved him from the chaos and violence around him. As a young boy, he had lashed a wooden crate to a utility pole outside their house and played alone for hours. It disciplined his mind and his body, gave him something to reach for.

He loved and respected his brothers, Mike and Milton, but their gang life also brought him pain. His boyhood friend Junior had joined their group and wound up dead. Another childhood friend, , also joined, becoming a violent soldier for the Outlaws. He was now gone, too, in prison for life.

To escape his brothers’ orbit when he was 14, Nugget convinced his parents to let him move out of the section of the two-family house where the rest of the family lived and into a room in the apartment upstairs. But the war followed him there. Because that apartment carried a different address from their family’s, Milton and Mike began to store their growing arsenal of guns in Nugget’s new room because any search warrants likely wouldn’t cover it.

Conflict area of Cape Verdean War

“I saw every kind of weapon my brothers went to war with before I was 15,” he said.

Through it all, basketball was Nugget’s constant companion. He had become a standout player in high school. As Alex grew older and showed similar promise, Nugget wanted to give that chance to him, too. The two played almost every day, drilling, practicing, thinking through the game. They became close, almost like father and son.

After Luis died, it all changed.

Alex later wrote in a college admissions essay that his brother’s violent death had forced upon him a frightening realization, that in a single, capricious instant everything Luis was and had worked to become was simply gone. “And in that moment,” he wrote, “I felt a part of me slip away like the smoke that quickly rises and disappears after the flame on a candle has been put out.”

He broke away from Nugget and “started missing school and hanging out with tougher kids,” their sister, , said. “He became tough, too, and started expressing his pain like Milton and Mike did. He learned by watching them.”

Alex DoSouto, at English High School, where in 2010 he drew praise from the academic and athletic staff as he tried to overcome his troubled past. (Jonathan Wiggs/Globe Staff)

Left: Steve "Nugget" DoSouto visited the grave at New Calvary Cemetery shared by his slain brothers, Luis and Alex. Right: Alex DoSouto's basketball trophies symbolize the hope his family had for his future. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

The trouble Alex got into was small at first – trespassing, marijuana possession, disorderly conduct. But he took a more ominous turn. He formed his own gang and, with that crew, seemed hungry to inflict fear and pain. They prowled at night, hunting for victims and robbing them at gunpoint, sometimes with what would seem unnecessary cruelty.

On a February night in 2008, he drove three others to Quincy and waited in the car while two of them accosted a man walking home from the T. One held a gun to the man’s head. The other told him they would pull the trigger if he didn’t hand over his money. The group allegedly robbed two others that night before police caught up with them, discovering a chrome-plated gun, a victim’s wallet, and cash. Alex and the others were locked up on felony charges.

Out on bail by summer, Alex was arrested again, with two accomplices, for beating and robbing two men at gunpoint in the Back Bay.

In May 2009, Alex was free again on bail and sitting on his family’s front stoop with a member of Mike and Milton’s gang who had been instructed to protect him. At dusk, a car rolled by and two shooters opened fire. One bullet struck Alex in the leg. Many others struck the house. Alex would recover, but the attack was a wake-up call. With a kind of introspection that can seem rare on the street, he told himself, “I can’t keep living like this.” And he did something about it.

Advertisement

With the help of a community street worker, Alex enrolled in the fall of 2009 at English High School, whose new Scholar-Athlete program helped last-chance kids like him.

A teacher, Rene Patten, picked him up every morning at 6:20 to make sure he reached school safely, then tutored him. Almost overnight, he became exuberant and optimistic again.

“Whatever happened in his life, Alex is filled with buoyancy,” English headmaster Sito Narcisse said at the time. “We’re very excited about his prospects.”

“If it wasn’t for Alex mentoring me, I wouldn’t have graduated from high school.”—Alex Almonte, Alex DoSouto's classmate

Alex had done poorly in school earlier in life. But now he excelled not just in entry-level classes but advanced courses. In honors English, he coached classmates through challenging literary works including “Oedipus Rex.”

“If it wasn’t for Alex mentoring me, I wouldn’t have graduated from high school,” one classmate, Alex Almonte, said.

Alex was leaning on Nugget again, too. They went regularly to the neighborhood Marshall Community Center to train for the upcoming season. One day, they rushed to the aid of a young friend who had been shot in the gym, a brazen ambush that would forever alter Nugget’s life. From that moment on, he would dedicate himself to trying to save the community’s youth, Alex among them, from violence.

Nugget helped Alex become a team captain at English, one of the city’s top playmakers. Alex scored as many as 30 points in a game and led English to a 13-7 record and the state tournament.

Steve "Nugget" DoSouto, coaching and officiating a game during the Lil Rim basketball program at the Holland Community Center in Dorchester, has dedicated his life to saving children in the community from violence. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Left: Steve "Nugget" DoSouto's nonprofit Beantown SLAM runs programs throughout the summer at Ronan Park in Dorchester for youths at risk of violence. Right: Milton DoSouto's son, Alex, named for Milton's slain brother, went up for a practice dunk in his uncle Nugget's program for preschoolers at the Holland Community Center. (Craig F. Walker/Globe staff)

“Thank God for that young man,” said Barry Robinson, the head coach. “I don’t think we would have won too many games without him.”

Alex was named the team’s most valuable player and selected to play in the Boston City League All-Star Classic. His dream of getting away to college, which once seemed lost, was now tantalizingly close; he committed to play at West Virginia’s Potomac State College, a two-year institution, intending to move on to North Carolina A&T State University, a historically black college with a Division 1 basketball team.

It was a triumph. But his adversaries continued to stalk him. Before a semifinal game in the city championship tournament at Madison Park High School, Mike – who, along with Milton and Nugget, attended all of Alex’s games – spotted members of an enemy gang following him into a bathroom. Mike entered behind them and drew a knife.

“One of the kids was getting ready to stab Alex,” Mike said. “I felt guilty stabbing the kid first, but they had Alex cornered and would have done something horrible if I didn’t start stabbing him.”

Mike snuck out through the lobby amid the ensuing chaos. Alex returned to the court and finished the game. But it wouldn’t be his enemies’ last attack.

Relocating far away to college was Alex’s best hope of removing himself from danger. Now, only one major roadblock remained. He awaited trial for the Quincy robbery after a jury had found him not guilty in the Back Bay case. His family hoped that the fact he was just the driver that night would help persuade the jury to acquit him.

Just days before his trial, while Alex was held in the county jail, two members of his Homes Avenue gang, with which he remained involved, shot and killed an innocent 14-year-old boy, Nicholas Fomby Davis, mistaking him for his older brother. The crime set off an outpouring of anger.

Boston police, under pressure to crack down, launched a self-described “shame campaign,” distributing a flier resembling a wanted poster in Alex’s neighborhood and to the media. The flier displayed the mugshots of 10 suspected members of the gang, including Alex. It went out on the first day of his trial.

Alex DoSouto, applying defensive pressure during an English High game against Hyde Park High in 2010, was his team's most valuable player and a Boston City League All-Star. (Matthew J. Lee/Globe Staff)

“The Boston police should be ashamed of themselves,” Lefteris Travayiakis, Alex’s lawyer in the Back Bay case, said at the time, suggesting the campaign was an attempt to sway the jury.

Whether the campaign had any impact, the jury returned a guilty verdict.

As Alex awaited sentencing, support flowed from many corners.

A Globe editorial urged the judge to “opt for a lighter sentence” that would not derail Alex’s college plans. Alex “should be allowed to pay his debt to society and move on,” it read.

, the English High headmaster, ached with disappointment. “It’s very painful for a lot of us at the school because Alex changed his life,” he said. “We’re hoping the judge allows him to go to college, out of Boston and out of the neighborhoods.”

Alex’s supporters filled the courtroom at his sentencing. Judge Janet Sanders rejected both the prosecution’s recommendation of a five- to seven-year sentence and Alex’s request for probation. She imposed a sentence of two to three years in state prison, driving a nail into his chance to reach West Virginia.

“The fact was that for several years he was running with a very bad group of people and was convicted of a serious crime, and he will have to pay for it,” Sanders told the courtroom.

The Rev. Richard “Doc” Conway, at St. Peter Church in Dorchester in 2024. Conway led the funeral Mass for Alex DoSouto at the church in 2015 and appealed for an end to gang and gun violence. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

When Alex was released from prison in 2013, Nugget was waiting to drive him home. Starting life again, Alex reunited with a young woman he had dated in high school, . She had spent a year at St. Michael’s College in Vermont while he was in prison but was now back home on Bowdoin Street.

She took him to see the Los Angeles Lakers and his hero, Kobe Bryant, play the Celtics at TD Garden. They imagined a future together. On Christmas, he gave her a Tiffany infinity ring. She gave him his favorite Kobe sneakers.

“When I pass away,” he told her, “bury me with my Kobes.”

Alex enrolled at Roxbury Community College, played on the basketball team, and posted good grades.

“I was falling in love with watching him do everything he needed to do for himself in sports and academia,” said the team’s coach, Kwami Green.

But Alex was still in Boston, still facing danger. And it came for him again on Jan. 8, 2015. That day, as usual, he was the first to report to the Roxbury college gym for practice. Afterwards, he went home and proudly showed Milton his new team shoes, bright orange. Then he visited Aissa, who was washing his uniform and cooking dinner.

She sent him off with a plate of shrimp and rice. He drove to pick up a couple friends and then went to Roxbury to get another. They were idling in front of the friend’s building when gunfire erupted. Glass shattered. Alex was hit again and again, including in the head.

A text appeared on his phone from Aissa: “Where are you?”

Advertisement

Milton’s phone rang.

“Come see me at the hospital,” the voice on the other end said.

“I asked him what happened, and he hung up,” Milton recalled. He knew something was very wrong.

Milton, Mike, and Nugget raced by car from hospital to hospital, trying to find their brother. By the time they located him at Boston Medical Center, a police cruiser had arrived at the DoSouto home. Their younger brother rose from bed to find two officers at the door. Their parents were sobbing. A cop was crying, too.

Alex, the officers said, is dead.

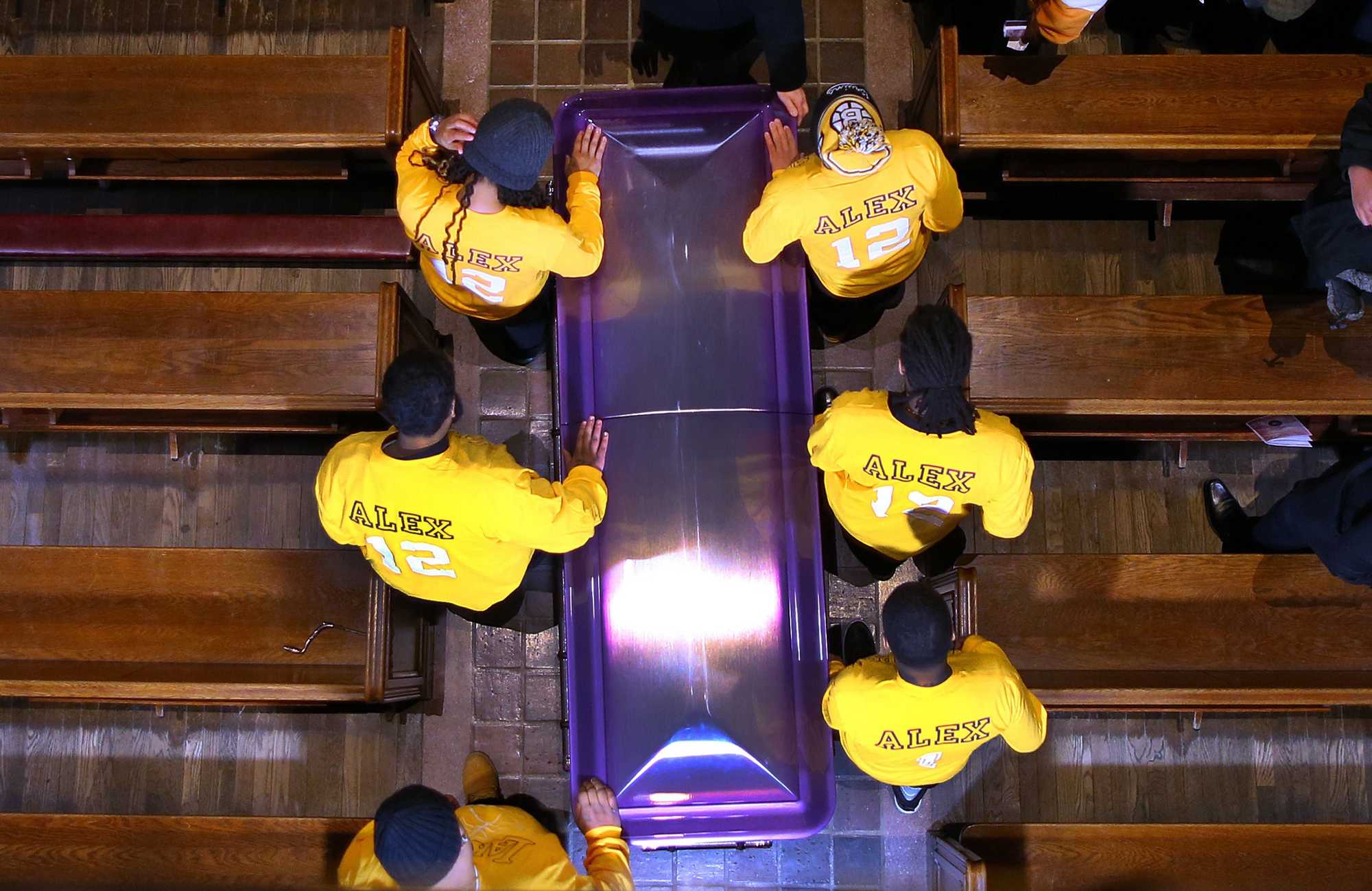

The funeral Mass for Alex DoSouto reflected his adoration of Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant. At the family's request, a casket the color of Lakers purple was found in Texas and shipped to Dorchester for them. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

As Mike walked out of the hospital, he punched his car window, shattering it.

Milton began making calls, trying to identify Alex’s killer. And Nugget phoned someone he once knew. For the first time in his life, he wanted a gun.

By 4 a.m., he was gripping a pistol. He pulled a hoodie tight around his head and donned baseball gloves, known to some as murder gloves because they keep incriminating fingerprints off a weapon.

“I was ready to kill,” he said.

He didn’t know who yet, but he aimed to find out. He eavesdropped on Milton’s phone conversations and made a couple of his own. Hours passed until his vigil was interrupted by a call from the medical examiner about identifying Alex’s body. Nugget went with Christina. They stood in a brightly lit waiting room before someone emerged with a photograph. It showed the unmarred side of Alex’s face, sparing them the sight of the part they would no longer recognize.

At the funeral home, there were decisions to be made about a casket (they chose the Lakers color purple) and what to bury with Alex along with his Kobes. Christina and another sister braided Alex’s hair. It was then, in the presence of Alex’s body, in the bleak silence of the undertaker’s parlor, that Nugget broke down.

As he sobbed, he realized his murderous rage was dissolving into another feeling, of a bottomless grief that nothing could salve, not even revenge.

“Killing somebody wasn’t going to bring my brother back,” he said

Hundreds came to the funeral at the big stone church where Luisa DoSouto had brought her children when they were small. , the peace activist who had also lost two sons to the war, came. She knew Alex’s parents and their pain. One of the Outlaws tried to turn her away at the door but she pressed on.

Outside the church walls, police were preparing for the possibility that Alex’s death would trigger a wider eruption of violence. Inside, the priest, the beloved Richard “Doc” Conway, who had worked for years with young Cape Verdeans involved in the war and had learned to speak their native Creole to better reach them, spoke of gun violence tearing apart families and communities. “Why did this have to happen?” he said.

And, he asked, when will it end?

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporter: Bob Hohler

- Editors: Steve Wilmsen, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Craig Walker, Matt Lee, John Tlumacki, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Digital editors: Christina Prignano, Katie McInerney

- Design: John Hancock

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara-Smith

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Adria Watson

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC