A stabbing in Dorchester ignites an all-out war. One family becomes the perpetrators — and the victims.

Milton DoSouto parked his car along the cemetery road and labored with his cane to walk toward the gravesite of his two slain brothers.

He looked around for signs of danger. He was vigilant wherever he went, but this place, New Calvary Cemetery in Mattapan, had been especially perilous. His enemies came to visit their own dead; he’d been shot at here before. But all was quiet now. He kept moving.

Blood on the streets

![A stabbing in Dorchester ignites an all-out war. One family becomes the perpetrators — and the victims.]()

Part 1: A stabbing in Dorchester ignites an all-out war. One family becomes the perpetrators — and the victims.

![Their brother’s death in the Cape Verdean gang war sparks another violent chapter. When would it end?]()

Part 2: Their brother’s death in the Cape Verdean gang war sparks another violent chapter. When would it end?

![‘I don’t want to fight no more’: Members of the Outlaws take stock of the destruction — and seek atonement]()

Part 3: ‘I don’t want to fight no more’: Members of the Outlaws take stock of the destruction — and seek atonement

It was 2019. He was 38 years old, trying to make it to 40. He had a child and a stable life a few miles removed from the Dorchester neighborhood where he grew up and where years before he had made himself a feared gang lord at the center of a historic conflagration of violence known as the Cape Verdean war.

The war pitted family against family, tore apart childhood friendships, and sowed fear for more than two decades in the Cape Verdean community in Dorchester where it broke out. The ferocity and pace of the killing baffled city leaders, who seemed powerless to stop it. Gunfire erupted almost daily, on street corners, from car windows, front porches, one backyard to another. Milton and , both victims and leading perpetrators of the violence, ran one of the war’s most notorious gangs. One probation official remembered them for their “cold lifeless eyes.”

Milton had groomed young friends and cousins into loyal street fighters. He led with charisma, and they followed, raining vengeance on enemies who were equally bent on killing them. In his view, they were not stone-hearted killers. They were fighting to defend themselves and their families.

The only remedy for the violence proved to be the passage of time. Some members of Milton’s crew were now dead or in prison. His immigrant parents were old and suffering after lives battered by loss and what felt like constant attacks on the home they had worked day and night to buy. His surviving siblings struggled in their own ways, too. Milton himself was tormented by guilt about the role he played and the cruel price his family, and others, paid.

Even so, he had not fully extracted himself from the war, which was greatly diminished but remained menacing. He knew he was still a target. And as he approached the grave to visit his brothers, he saw fresh evidence of an enemy’s hatred. The tombstone had been desecrated. An image of his older brother, , etched into the granite, was shattered and pocked, as though struck by a bullet. A framed photo of his younger brother lay smashed on the ground. The statue of a lion that had stood guard over the monument was destroyed.

It was a blatant provocation, an insult to Milton’s dead brothers and his entire family. He instantly knew which rival gang was responsible and felt a surge of rage, a reflex that for much of his life had spurred him and his crew to retaliate. This time, to his astonishment, he reacted differently.

Inching closer to the defiled tombstone, he steadied himself with his cane, and lowered his head.

“I started bawling,” he said. “I couldn’t wake up the devil inside me anymore.”

Milton DoSouto approached his family home (right) on Hamilton Street, where he and his brother Mike formed the Cape Verdean Outlaws during a deadly, decades-long street war. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Milton left the cemetery that day thinking about the life he had known and somehow survived. He was 13 when a dispute in the community exploded into gun violence, 15 when he first ran from bullets fired at him, and no more than 17 when he — along with his brother, a cousin, and a friend — began to shoot back.

The violence that defined his life and innumerable others in the Cape Verdean community commanded headlines and raised serious public policy questions about preventing and combating gun and gang violence in an emerging immigrant community. Today, many of the war’s combatants are dead, incarcerated, or have passed into the subdued rhythms of middle age. The conflict has largely faded from public view, forgotten except by those who endured it or tried to stop it. Death is no longer a daily headline. Boston has become a city with a remarkably low murder rate. Last year there were just 24 homicides, the fewest since 1957.

But the story of Boston’s Cape Verdean war has never been fully told or understood, in large part because the players involved haven’t talked much about it. It is a hole in the town’s history, a gap that some of the DoSoutos have chosen to close by opening up, often with stunning candor, to the Globe. They have learned the hard way that historical amnesia is dangerous. Yet as they take a first big step toward building a lasting peace, they share the fear of some community leaders that grudges born years ago still run deep and could erupt again at any moment, especially if authorities repeat the mistakes they made early on.

For years, policy makers failed to grasp that the Cape Verdean war differed in its essence from past gang violence. It was a blood feud fueled not by beefs over money, drugs, or turf but by viscerally personal vendettas inflamed by poverty and the failures of Boston’s police force, schools, and service providers to build bridges to the many Cape Verdean emigres who settled here.

“Suddenly, the Cape Verdean problem popped up, and nobody knew how to deal with Cape Verdean kids,” said Bill Stewart, the former assistant chief of probation for the Dorchester District Court who participated for decades in efforts to quell gang and gun violence. “We were culturally ignorant for the most part.”

Paul Joyce, a former Boston police superintendent who led the department’s operations against gang violence, said, “Between the community and the police, we never really were able to solve the problem.”

Mayor Michelle Wu’s senior adviser for community safety, Isaac Yablo, has studied the war and found a correlation between the government’s deficient support for the Cape Verdean community and the killing.

“As a city,” he said, “we were complicit.”

The war was propelled by violence itself, each new shooting retaliation for another in an ever-escalating cycle that spiraled beyond anyone’s control. More than 65 lives were lost. Many more people were wounded, some permanently.

“I recall that nobody seemed to remember what they were fighting about,” said Sydney Hanlon, a former longtime first justice of the Dorchester District Court who presided over hundreds of criminal cases stemming from the war. The one common thread, she said, was retribution.

In 1994, the DoSouto family bought a pale blue house on Hamilton Street in Dorchester’s Bowdoin-Geneva neighborhood, with all the hopes and aspirations of any immigrant family, for a better, more prosperous, more peaceful life. They had no way of knowing that the neighborhood was about to ignite, much less the role their family would play. And in the bloody decades that followed, their world and that of their 10 children would be altered forever by a distinct American tragedy from which city leaders continue to try to draw lessons.

Brothers, from left, Anthony DoSouto, Mike Fernandes, Steve “Nugget” DoSouto, and Milton DoSouto stood outside the Holland Community Center in Dorchester. Their parents emigrated from Cape Verde in 1982. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Advertisement

A and emigrated from Cape Verde in 1982 with their little boys, Luis and Milton, on their laps. They knew little English and labored long hours in factory and service jobs. Luisa bore an additional burden: She was pregnant almost all of those early years while they were barely scraping by. There was little time, energy, or money for nurturing. Alfredo tried to keep Milton and Mike in line by beating them for misbehaving. On Sundays, Luisa led the children to Catholic Mass at the big stone St. Peter’s Church on Bowdoin Street. Apart from that, the children were largely left on their own to navigate the world they found themselves in: a place of hardship and danger, a place where weakness could prove fatal.

Cape Verde is located off the northwest coast of Africa

They were so poor that even in a community where many people struggled to pay the rent, Mike recalled, they “stuck out like a sore thumb.”

The children wore hand-me-downs and free clothes distributed at school. They hustled for small change and handouts — tracking down grocery carts for the supermarket, or cleaning the floor at the doughnut shop. Sometimes, they went to a neighborhood center, the Dorchester Youth Collaborative, run by a well-known community leader, Emmett Folgert.

“When we were starving, we would go to the DYC because Emmett would give us a few bucks to eat,” Milton said.

Their neighborhood was notoriously tough, a place where gang violence had grown more hazardous over time. An epidemic of shootings among predominantly Black gangs that peaked in 1990 with 152 homicides in the city had been largely quelled before the DoSoutos moved in, the result of an unprecedented alliance among government, faith, academic, and community leaders that came to be known as the Boston Miracle. But even as gun violence receded, danger did not. The streets remained treacherous, especially for young men and boys.

The death toll, 1995-2021

Gang and gun violence during the Cape Verdean war claimed more than 65 lives, nearly all in Dorchester’s Uphams Corner and Bowdoin-Geneva neighborhoods. Cape Verdean gangs of all sizes operated out of at least 15 streets in Dorchester and Roxbury during the decades-long war. Some gangs have merged. Others no longer exist. Most of the dead were directly involved in the war, but some were innocent victims. The circumstances of many cases are not fully known because they remain unsolved. Explore the locations of the deaths, some of which are listed because of their proximity to gang hot spots. See the key streets by zooming in.

- Fatality (Tap for details)

- Boundary of conflict

- Streets where Cape Verdean gangs operated out of

“It was survival of the fittest,” said George Michaelidis, who ran a neighborhood pizza shop and kept an eye on the DoSouto children.

The older boys – Luis, Milton, and Mike – looked out for their siblings. Even as young teenagers, they were big and imposing and bravely faced down aggressors.

Luis, the oldest, was round and affable with a friendly face, except on the rare occasions he was angered. Milton was quick-tongued and quick-tempered, while Mike was terse and fierce. Even as a boy in school. “I hated being around people,” he said. “You couldn’t teach me anything. I didn’t care to talk to anyone.”

In sixth grade at the Dearborn Middle School, Mike was expelled for punching and karate-kicking the principal because “he wanted me to do something I didn’t want to do.” At 13, he was found delinquent in juvenile court for trying to stab a man who had insulted his friends and push the man from the Red Line’s Downtown Crossing platform into the path of an oncoming train.

Luis managed to get by in school. Milton and Mike did not. They spent more and more time on the street with two other kids – a cousin named and a friend they called . Barely adolescent, they mostly hung out, flirted with girls, played basketball, made their own rap music, and shoplifted from local stores — both for the thrill and to have something to eat before they were old enough for real jobs.

They watched each other’s backs and were quick to throw punches at anyone who tried to mess with them or their siblings. As trouble escalated, they started carrying knives.

They also developed a lucrative side hustle. Watching the reality TV show “Cops,” Milton and Mike learned a trick to thwart electronic theft detection devices by lining shopping bags with aluminum foil, enabling them to systematically rob downtown department stores. They brought home bags full of clothes for themselves and their families and sat in a corner of the pizza shop, covertly peddling CDs, video games, and other stolen goods. They made real money. They were still kids, but they felt like kings.

Alfredo DoSouto paused on the doorstep outside his home on Hamilton Street in Dorchester. He had no way of knowing when he moved there with his wife and the first nine of their 10 children that four of his sons would be shot, two fatally. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Years later, authorities trying to understand the roots of the Cape Verdean war would realize the community had been allowed to grow thick with small street crews like the DoSoutos, composed largely of the children of immigrants — brothers and cousins and close friends with deep loyalties to their families, each trying to protect themselves. Most weren’t yet dangerously violent and largely operated under the radar of police. But tensions grew ever more combustible, until a single spark ignited a decades-long war.

Advertisement

The flashpoint came on Oct. 10, 1995, when started a fight about a half mile from the DoSouto home, across busy Columbia Road near densely populated Wendover Street, where a number of Cape Verdean clans lived. A 23-year-old named jumped into the fray to defend his cousin and was stabbed fatally in the heart.

Enraged and vowing revenge, a group of Mendes’s friends who lived nearby went after the knife-wielder’s friends. The stabber, Nardo Lopes, fled the city, but his brother, , stayed to fight on his behalf. Gus would join a Cape Verdean crew based just around the corner from the DoSouto house, on Stonehurst Street, and launch attacks against the Wendover gang.

The dividing line of Columbia Road

The fight rapidly intensified, each gang attacking the other, each new shooting setting off a burst of retaliatory violence. Columbia Road, a gritty, high-traffic artery that roughly bisects the neighborhood and the nearly 10,000 Cape Verdeans who lived there, became a dividing line between the enemy camps. As the violence grew, new crews formed until no fewer than 15 street gangs with about 230 members were engaged in the conflict. Milton and Mike didn’t know it yet, but their little group — still young teenagers — would emerge as one of the most feared.

The way Milton and Mike saw it, they never wanted war, never sought to become what police would call them: “volatile impact players,” gun-slinging purveyors of lethal violence. Rather, they were drawn into it, beginning around 1996 when Milton was 15. He was standing on a corner a block from his house, on a commercial strip along Bowdoin Street, when two boys confronted him. One pulled a gun and started firing. Milton had never been shot at before. He ran home in terror, zig-zagging as bullets kept coming. His mother stood on their front porch, watching helplessly.

Then, when Mike was 16, he took a bullet while riding his bike nearby. More attacks followed, and the brothers realized why. The Wendover gang from across the divide believed Milton and Mike were aligned with Wendover’s archenemy, the Stonehurst gang based around the corner from the DoSouto home.

Under siege, Milton phoned Wendover’s leader with a message: He and Mike were not affiliated with Stonehurst and had no beef with Wendover. To further distinguish themselves from Stonehurst, Milton and Mike gave their group a name: the Cape Verdean Outlaws.

They also got guns.

Milton’s message was lost on the Wendover crew. The attacks became more frequent, and soon Milton, Mike, and the Outlaws were firing back. What’s more, had begun waging brazen retaliatory strikes on Wendover turf. They were never certain if his bullets struck anyone, but his incursions were nonetheless provocative.

To this point, none of the Outlaws had been seriously hurt. But in June of 2000, a Wendover shooter, armed with a pistol equipped with an extended clip, ambushed Milton and Mike while they were out walking, forcing them to crouch behind a truck while bullets zipped through the air. Mike tried to shoot back, but his gun jammed. The shooting eventually stopped and the assailant fled. Milton and Mike narrowly escaped, but the war was ever more violently closing in on them.

A day later came another attack, this one against Junior. He was walking through a small park in front of the white-steepled church across from St. Peter’s when a Wendover shooter burst out of a van and started firing. Junior, born Pedro Sajous Jr., was 17. He returned fire but took a bullet in his torso and died that night.

Life would never be the same for Milton and Mike. Until then, they were kids thrust into a risky game of war. Now they’d seen a friend die. They wanted blood.

“When we lost Junior, that’s when the whole war between us and Wendover got out of control,” Milton said.

A look at those involved in the conflict – and the efforts to stop it

Luis DoSouto

DoSoutos/Outlaws

The oldest of seven brothers, Luis was a chef at the former Bayside Executive Conference Center. He was shot to death in front of his family’s home in Dorchester in 2006 at the age of 25.

Through the bloody seasons that followed, the assaults on both sides became more audacious, the stakes more personal. There were shootouts outside the DoSouto house, including one when the Outlaws ran indoors chased by police and shocked Milton and Mike’s mother by handing her a pistol to hide. There was an attack outside the Madison Park prom at a harborfront hotel. And yet another, when Milton was shot in the chest in front of an auto body shop in enemy territory by a gang allied with Wendover. Miraculously, he was not seriously hurt.

Milton and Mike soon amassed an arsenal of weapons that included assault rifles. And they relied more heavily on a newer member of their gang, , to carry out armed attacks. Fernandes was a skinny kid who lived around the corner. He had arrived from Cape Verde when he was 11, unfamiliar with the English language and American culture. He had found a friend in a younger DoSouto brother, But Odair became enthralled with Milton and his aura of danger and power, and Milton had groomed him for a role in the gang.

“He gravitated toward me, and I said, ‘If you’re going to be next to me, I need you to stand with me because I don’t run,’ ” Milton said. “I would punish him. I would beat him up to the point of almost crying. I was toughening him up.”

Odair stood up to the beatings. He became ruthless — and doggedly loyal. More than once, Milton said, “he saved my life because he was that violent.”

The Outlaws came to consider every attack on them a mandate for retaliation with equal or greater force. It was a code of honor and, they felt, their only option, as though any show of weakness would only invite more violence. But there was an element of recklessness written into the code; it didn’t always matter if the perpetrator of an attack was the one targeted for vengeance so long as someone — anyone — on the other side suffered.

One day, while Milton and Mike were hanging out in front of their house with their girlfriends and brother Luis, a Wendover gunman darted around a corner and opened fire. Luis, shielding Mike’s girlfriend, took a bullet. It wasn’t a life-threatening injury but Milton and Mike were wild for vengeance.

They rushed to a Chinese restaurant in enemy territory where they knew Wendover members congregated. Mike burst through the front door, surprising several Wendover members, who bolted out the back. Milton and a cousin, both armed, then went to Wendover Street and started walking, inviting confrontation. A car pulled up. Milton began firing.

“I didn’t know who he was,” he said. “I just knew he wouldn’t stop like that if it wasn’t his neighborhood.

“I was so enraged that I wasn’t even aiming. I saw sparks from the first two bullets hitting the street, and I almost shot my cousin. Come to find out, the guy had nothing to do with Luis’s shooting. It just came down to whoever I could find.”

Milton DoSouto described a shooting he witnessed in which the victim was shot in the head. He himself barely survived seven gunshot wounds that left him partially paralyzed. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Milton’s mother had raised him in the church, and sometimes he still attended with her. At night he prayed for everyone’s souls, even those of his enemies and those he had harmed. He knew that the violent path he had taken would not please the God he prayed to and that there might come a time he would answer for it. He told himself he would rather die than spend his life in a wheelchair. And he knew, as a leader of the Outlaws, that Wendover surely was hunting him, waiting for an opportunity to take him out.

The moment came in April 2003, the day after his , angry that he had bullied a boy she had a crush on, shouted, “I hope you get shot up.”

As Milton stood around the corner in front of Odair’s house, a black car sped around the corner, tires screeching. A gunman inside had a .45 semi-automatic and a clear line of sight.

Seven rounds ripped into Milton’s body.

“I was standing there frozen,” he said. “The bullets kept coming, and my body kept twitching every time I got hit.”

He crossed himself and fell face-first onto the pavement. His family, including Christina, came running at the sound of gunfire. They wailed as Nugget and Odair held him, Odair pressing a towel against his wounds.

The last thing Milton remembered was the look in their eyes. “It told me I was dying.”

When he awoke from a coma three days later, his mother was beside him. God had come to him while he slept, he told her, and said he must reject violence. Milton promised he would.

“God told me, ‘I got your back this time, but no more chances,’ ” he said.

Milton underwent multiple surgeries at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, then spent months at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. A bullet had damaged his spine, partially paralyzing him. A doctor told him he would never walk again or have children.

At his bedside, the Outlaws tearfully vowed furious retaliation. Milton told them to stand down, but 11 nights later Odair and several others were apprehended by police in the brazen shootings of two friends of Milton’s assailant. One died instantly. The other, a cousin of Bobby Mendes, was left paralyzed from the neck down, blind in his left eye, and dependent on a respirator to breathe. He died four years later. Odair was 19 on the night of the attack. He was convicted and sentenced to prison for life without parole.

In time, the doctor’s prognosis of Milton’s future would prove to be wrong. Milton would walk again, though painfully and only with the help of a cane. He would no longer fight in the streets or inspire fear with his menacing swagger. But he continued to help rule the Outlaws. He had made an oath before God against violence. But there was a war on, unrelenting and seemingly unstoppable.

God might have to wait.

Two years passed before Milton managed to climb unassisted out of his wheelchair. By then, another of the original Outlaws, Joseph Lopes, had died in a hail of Wendover bullets. Milton and Mike were left to lead the crew in their own ways. Mike was the money man, finding methods, legal and illegal, to help support the war effort and the family. Milton worked his phone, staying abreast of action on the streets, sometimes trying to persuade enemy leaders to help him diffuse tensions. But he still held sway over the Outlaws ready to do the crew’s most violent work.

Then came a warm spring night in 2006. A half moon glowed against a black sky as Milton’s older brother, Luis, crossed the street to attend a friend’s party. Luis was 25 now, a successful chef with a recent offer to run the kitchen at a new restaurant. He had kept himself out of gang life and the war. He was known in the neighborhood for helping mothers carry groceries and for opening a hydrant for kids on hot days. Everyone seemed to love him.

Luis strode into the party with a big smile, his hair neatly braided by his sister Christina. Beer in hand, he circulated, moving to a hip-hop beat.

At 2 a.m., the music stopped, and Luis joined the crowd spilling into the night. Then a skirmish erupted. Someone drew a gun and shot Luis point blank through the heart.

Christina, hearing gunfire, bounded down the stairs of their house. Nugget knelt by Luis in the street, gripping his hand. Milton burst out of the door, limping hurriedly with his cane.

Blood spread across Luis’s white T-shirt as Christina crouched over him, desperately performing CPR. “Stay awake,” she implored him. “I’m here. Stay awake.”

Luis let out a breath. He was gone.

Milton cried out in grief.

“Not my brother!” he shouted. “Why not me? I’m about that life.”

Police were nearby and promptly arrested a teenager who sprinted from the scene, tossing away a Glock 9mm as he ran. He had no apparent affiliation with Cape Verdean gangs or known ties to Wendover. But as the hours passed and Milton and Mike listened to their grieving mother’s wails echo through the house, they thought only of revenge and the enemy they knew best. Their brother was dead. It was clear to the Outlaws that someone from Wendover must now die, too.

Advertisement

Isaura Mendes, a peace activist, stood outside her home while reflecting on the murders of her sons, Bobby and Matthew, in her Dorchester neighborhood. She painted her house green and purple because the colors to her represent courage and peace. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

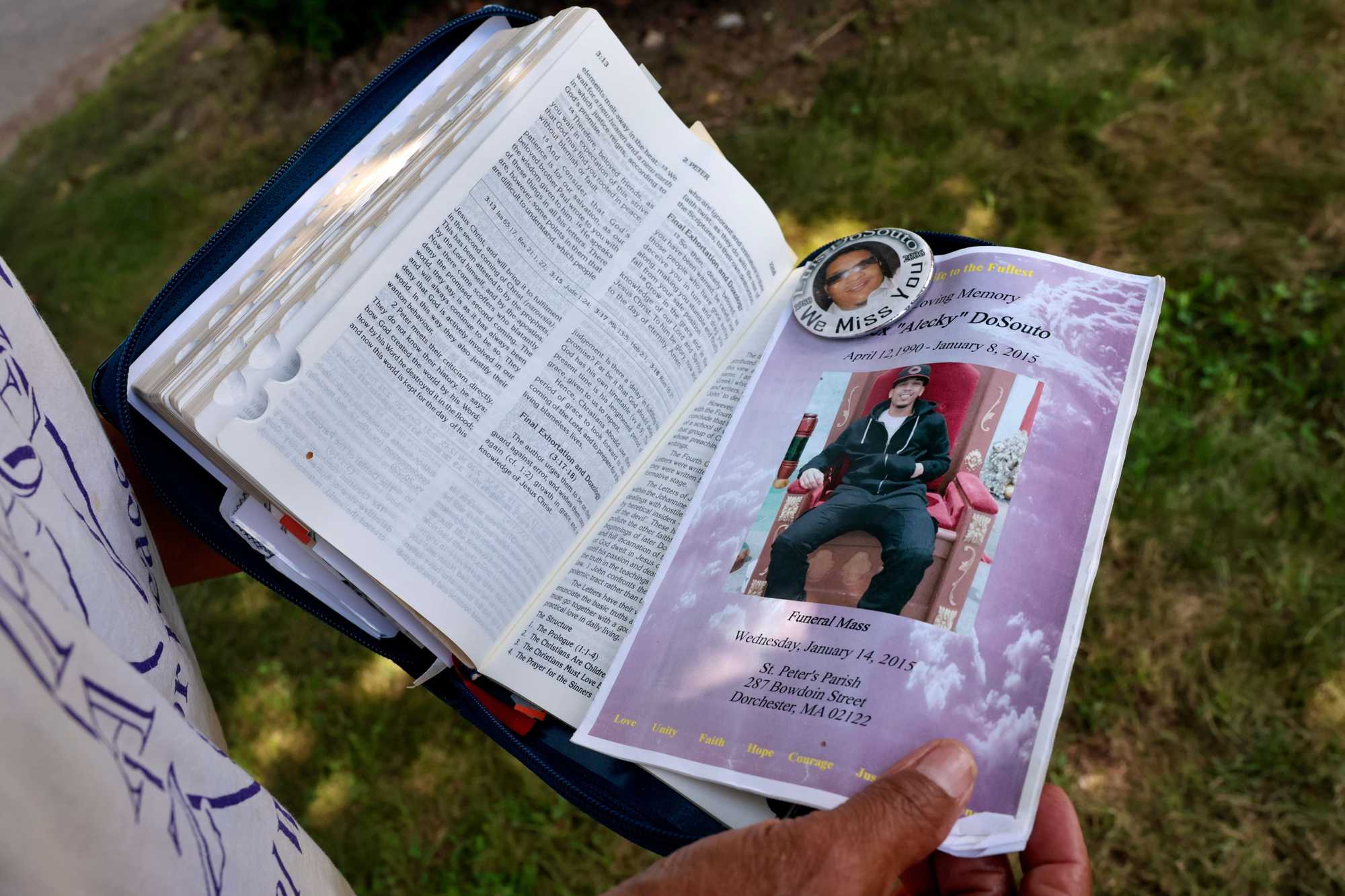

Left: Isaura Mendes keeps a Bible in every room of her house as well as her car. The Bible in her car contains a copy of the program from Alex DoSouto's funeral and a pin honoring his slain brother Luis DoSouto. (Craig F. Walker/Globe staff) Right: Mayor Thomas M. Menino consoled Mendes after her son Matthew was murdered, less than 24 hours after Luis DoSouto was slain in May of 2006. (Matthew J. Lee/Globe staff)

Just after dawn that morning, left her home on Wendover turf and ventured across the neighborhood divide to visit the DoSouto home and offer the family comfort.

She knew the DoSoutos well. They attended the same church. They were born and raised on the same tiny volcanic island of Fogo in Cape Verde. They might even be distantly related.

Isaura was also the mother of , whose murder in 1995 had triggered the war. Bobby’s death and the violence that followed had devastated her. She had loved her first son dearly, and she had cherished her life in America, immersing herself in the lively community that Cape Verdeans had made in this small corner of Boston.

Isaura loathed the fear and suspicion the war had brought. She had made it her mission to appeal for peace. Before her son’s death, she regularly visited neighbors and relatives to welcome newly immigrated Cape Verdeans and celebrate milestones. Now, she went to see the families of the dead.

She carried with her the memory of that evening years before, of a neighbor pounding on her door, of sprinting down the street and seeing her mortally wounded son on the ground. She had fainted from the shock.

She didn’t think she would ever recover. She secluded herself in grief. She bought a cemetery plot next to Bobby’s, unable to imagine living much longer without him.

When she visited families of the dead now, she offered herself as someone who had endured pain like theirs and as proof that life could go on.

Arriving at the DoSouto home, Isaura hugged mother Luisa, drew her a glass of water, and softly spoke about the shared pain of losing their first sons.

By the time she returned home, word of Luis’s murder was all over Wendover territory. Some were already bracing for an attack by the Outlaws.

“‘Mommy, we have to be careful,’” Isaura recalls telling her. “‘There might be retaliation.’”

Matthew, who honored his slain brother by campaigning with his mother against gun and gang violence, stayed inside most of the day. But the streets were quiet, and at around 10 p.m., he decided it was safe to walk four blocks to a friend’s building on Wendover Street. He was standing outside with several others when an unfamiliar white car approached.

Matthew and his friends, sensing danger, turned and dashed up the steps toward the foyer of the building. Matthew was a beat slower than the rest. A gun fired. Matthew was hit in the back. The shot pierced his heart, and he collapsed on the threshold, fatally wounded.

Once again, Isaura got word from a neighbor who came to her door, and once again she sprinted down the street, this time barefoot, to discover a son near death. Police and paramedics were already there and held her back as she struggled against them, crying out her son’s name.

Police investigated but never apprehended a killer, leaving Isaura tortured by uncertainty along with renewed grief that would haunt her.

Milton and Mike were home at the time of Matthew’s death. They deny knowing who shot him. Milton says only that Matthew was likely a casualty of an unending war with a simple emotional geometry.

“You just continue the cycle,” he said. “We follow a sense of direction. When Luis died, people were going to go to where they knew. I’m not saying that’s why Matthew died, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was because we do what we’re conditioned to do. We take our pain over there, and when they’re in pain they bring it over here.”

Correction: Due to a graphics error, an earlier version of a map in this story incorrectly listed the name of a street near the DoSouto residence. The street is called Stonehurst Street.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporter: Bob Hohler

- Editors: Steve Wilmsen, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Craig Walker, Matt Lee, John Tlumacki, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Digital editors: Christina Prignano, Katie McInerney

- Design: John Hancock

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara-Smith

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Adria Watson

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC