Single-family

Single-family homes have been the predominant form of housing across most of the country for more than a century. Zoning rules in many places generally encourage the construction of these homes, while banning most apartment buildings.

LA MESA, CALIF.

It doesn’t take much for a life to fall apart. Tim Taylor can attest to that.

Taylor’s last eight or so years have gone like this: He got divorced and was forced to sell his home. He got sick and lost his job. He nearly died of congestive heart failure and blew through his savings to pay off medical bills. He found himself, entering his 50s, suddenly needing a fresh start, some space to turn his life around.

And he found it, in a friend of a friend’s converted garage, tucked into the rolling hills of this city just outside San Diego.

The apartment is just 400 square feet, with a modern kitchen big enough for one person to stand, and space, barely, for a full bed, a small dining room table made of imitation marble, and a medium-sized flat screen TV on a shelf. From outside, the place looks like an addition to the low-slung, brown-paneled single-family it was built onto. From the road you wouldn’t even notice it.

But it’s charming, even if the noise from the freeway nearby never quite subsides. Taylor has hung shelves in the corners for extra storage space, and he proudly displays keepsakes from his time in the Navy. A pair of windows reveal the San Diego sun as it sets into the hills each evening.

And for $1,695 a month — far less than the typical rent for a one-bedroom around here — it’s a rare affordable slice of suburbia that has helped Taylor get back on his feet in the community where he’s lived for over a decade. It’s cheap enough that the 53-year-old can sock away savings from his two jobs and hope to buy a condo where he can eventually retire and rest his heart.

“It is a blessing,” Taylor said on a recent morning. “And trust me, I’m not particularly religious, but I needed a blessing.”

Accessory dwelling units, more commonly known as ADUs or granny flats, have become an essential strand of the fabric in this suburban city of 60,000. Tucked among the single-family houses that pepper the landscape here, they house college students and nurses, aging parents and still-at-home 20-somethings, providing badly-needed homes in what has long been one of the most expensive places to live in America.

Indeed, this new kind of home within a home is sprouting in garages and backyards all over California, with tens of thousands of ADUs built here every year, putting at least a small dent in the state’s massive housing crisis. They have also helped facilitate a broader shift in how some Californians think about housing.

Massachusetts could do it, too.

The state, as the Boston Globe Spotlight Team has chronicled in this series, has a housing crisis to rival California’s. Here, as there, restrictive local zoning has long squashed new construction. And, here, as there, a massive shortage of homes has severely distorted the market, driving prices and rents far beyond the reach of so many.

The difference is that California, the poster child of 20th century suburbia, is starting to do something about it, passing a series of laws in recent years that take aim at a foundational pillar of the American way of life: the single-family neighborhood and the zoning that created it.

The result has been a wave of new homes in a state that is starved for them, from backyard ADUs to corner duplexes to mid-rise apartment buildings in suburban downtowns. It is finally providing some cheaper housing and giving more people like Tim Taylor a chance to stay in communities where they’ve built their lives.

La Mesa, Calif., features a growing variety of housing types, including backyard ADUs and denser mid-rise buildings downtown.

“People love the places where they live,” said Colin Parent, a La Mesa city councilor and housing advocate. “Sometimes those places have to change to preserve the things we love about them.”

Change is a hard sell, though.

As in Southern California, most towns in Massachusetts have long devoted the vast majority of their land to housing relatively few people on large lots, locking in single-family zoning through decades old laws and freezing denser housing out.

Many like it that way, but the consequences are undeniable. The typical single-family home in Greater Boston now costs about $900,000. Houses are impossibly scarce. Renters are struggling. People are leaving.

And unlike in California, the response by Massachusetts lawmakers has been relatively timid at best.

That could finally change next year. As part of a recently filed housing bill, Governor Maura Healey is pushing to legalize ADUs on every single-family lot in the state. If it passes, the rule would represent the most direct override of local land-use control in Massachusetts in recent memory.

While the cultural change would be big, the opportunity would be too.

ADUs do get built in Massachusetts, like these (clockwise) in Concord, Mattapan and Abington. But they remain few and far between, thanks largely to a maze of permitting rules that can vary widely from town to town. Now Governor Maura Healey is proposing legalizing them statewide, as California has.

Roughly 950,000 homes in Massachusetts have large enough yards to accommodate at least one ADU in their backyard, according to an analysis for The Boston Globe by Bequall, a California-based ADU builder, which relied on property records and parcel data. The city of Peabody alone could build nearly 8,000, Bequall estimated. Weston has space for around 3,000.

That’s 8,000, or 3,000, or however many homes for the Tim Taylors of the world, people for whom the current housing market makes no room.

“My last couple of years have been about learning to be happy again,” said Taylor. “This place is a big part of that.”

Advertisement

Zoning may seem boring or innocuous, but it is the DNA of a community.

It dictates what kind of buildings can go where, how tall they must be, even how much parking they must provide. It can spark growth or snuff it out, and make a place exclusive or diverse.

For decades, land-use rules in the vast majority of Greater Boston communities have overwhelmingly favored single-family housing. In most of the region, the default is big plots of land neatly divvied up for individual homes, each with their own yard and driveway.

More than half of cities and towns in Eastern Massachusetts mandate that some lots for single-family homes be at least one acre, according to a Globe analysis of local zoning codes. Some require a baseline of two acres, one and a half times the size of the playing field at Gillette Stadium, per house.

This is the legacy of decisions made in the decades following World War II, when suburbs around Boston rewrote their zoning to block many multifamily buildings — and the newcomers they feared would follow. It froze those towns in place, no matter the waves of growth that have transformed the region’s economy and housing market in the half-century since.

It persists because Massachusetts, with its centuries-old legacy of town meetings and local governance, leaves zoning almost entirely up to communities themselves. Three hundred and fifty-one cities and towns decide what can, and cannot, be built within their boundaries, a process that gives existing residents enormous say over whether towns should change or stay the same. No surprise, they often choose the latter.

“It’s a big struggle here to overcome that perspective,” said Marc Draisen, executive director of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, Greater Boston’s regional planning agency. “One of two things would have to happen to end single-family zoning. Either communities would have to come to that decision on their own, which seems highly unlikely. Or something even more magical: the Legislature ordering them to do so.”

Recently, though, the dynamic has begun to shift. Six states — from California to Maine, Vermont to Oregon — have enacted laws that aim to rethink single-family zoning, typically by permitting a wider range of uses on single-family lots. Details vary, but each allows modestly denser housing in any residential neighborhood, no matter its current zoning.

The idea is to allow the kinds of denser housing that fit easily into single-family neighborhoods and caters mostly to the middle class — the “missing middle,” in housing policy parlance. That could be something as small as an ADU or as large as a six-plex, or six connected units on one lot.

Vermont’s rule, which permits duplexes anywhere in the state and four-plexes in areas served by water and sewer, was passed earlier this year. Legislators see that as the beginning of their reform efforts. Maine’s law is very similar.

And it’s not just politically blue states: Similar reforms have been debated by lawmakers in Texas and earlier this year, the Montana Legislature voted to legalize duplexes in cities with more than 5,000 residents. Even they have seen the warnings from their neighbor to the west of what happens when modest housing is systematically banned.

“The driving force behind it was that nobody here wants our state to end up like California,” said Kendall Cotton, CEO of the Frontier Institute, a conservative think tank in Montana that helped drive the new rules. “It also just so happened that when we looked at the data, we saw what they’ve apparently seen, which is that zoning is the problem.”

Advertisement

Just a few blocks from La Mesa’s historic downtown, an unassuming alleyway is at the center of this city’s subtle shift from California’s suburban tradition.

The alley slopes up a leafy hillside, between two streets lined with pastel-colored single-family homes. Behind them, garages and sheds line the alleyway.

Over the last few years, those worn-down garages have been replaced by homes. At least ten “granny flats” have sprouted just on these two blocks, with color and design that echo the homes they’re built behind.

They house ailing relatives who need to be close to family and young couples seeking refuge from San Diego’s sky-high rents. For instance, near the front of the alley is 37-year-old Blaine Whisenhunt, who has shared a two-bedroom ADU atop a garage with his family for the last few years.

Every year brings more newcomers to the neighborhood seeking affordable refuge in these little homes. A couple moved into the two-story granny flat across the street that was completed two years ago. Before that, another unit went up just two houses down. A newly completed unit about a block away is empty, waiting for its first residents. Some of the units are cheap. Others are definitively not. Whisenhunt, who works in real estate photography and lives in a unit with his wife and kids, pays $2,500 a month, $800 of which is covered by a roommate who lives in the second bedroom. But he makes it work.

“It’s a nice neighborhood that we might not have been able to afford,” Whisenhunt said as he worked in his garage one recent afternoon, San Diego’s Orange Line trolley humming in the distance. “At this point, we’ve accepted a lifetime as renters if we want to live here.”

That’s what places like La Mesa are becoming. An old farming town that is fast absorbing newcomers from the ever-pricier city to its west, La Mesa offers streets — dotted with palm trees — that look straight out of 1960s California.

Across the country, cities and states are rethinking the concept of single-family zoning by allowing moderate-density housing types to be built on lots traditionally reserved for suburban-style homes. Policymakers hope those units will be cheaper than traditional single-family homes.

Single-family homes have been the predominant form of housing across most of the country for more than a century. Zoning rules in many places generally encourage the construction of these homes, while banning most apartment buildings.

When Parent arrived on the La Mesa City Council in 2016, California’s housing crisis had reached a breaking point. Home prices, for the first time, were double the national average. A surge in homelessness was unavoidable.

Parent, a 43-year-old former state housing appointee, is a self-described YIMBY (that’s “Yes In My Backyard”), and the only renter on the City Council in a city where 58 percent of households rent.

He helped prod La Mesa to adopt what was then one of the most progressive ADU ordinances in the nation, allowing them to be built “by right,” and with no additional parking.

There was worry that the new units would just simply become Airbnbs or radically alter the quality of neighborhoods. But after the City Council voted, the rules took effect relatively quietly and the controversy ebbed; La Mesa even expanded its program a few years later.

Today, La Mesa permits around 60 ADUs, often known in the Golden State as casitas, a year. Across California, nearly 25,000 were approved last year, outnumbering single-family home permits in some areas and accounting for roughly one-fifth of all new housing in the state. California has permitted more than 80,000 ADUs since the first law took effect in 2016.

Of course, not everyone loves them. One man who owns a charming yellow home on that alley in La Mesa, with a swimming pool in the backyard, misses the neighbor who used to sell popcorn out of his garage. Today, that garage is a new ADU.

But by and large, the units have become popular, so much so that an entire new industry has sprung up to build them.

Drive through any California suburb these days, and you won’t just see an ADU, you may well see a billboard for a company offering to build one in your backyard. Dozens of new companies compete to build the cheapest, most efficient models. Some mass-produce them on an assembly line; others build ground up in a backyard or experiment with two-unit models where allowed.

Zoning rules are relatively consistent from town to town, so developers know they can operate anywhere in the state. That predictability also lowers the cost.

John Arendsen, a manufactured home developer in the San Diego area, can build an ADU on an assembly line in about two weeks; his one-bedroom models sell for between $200,000 and $300,000.

“For a long time, the big cost was in the permitting process — entitlements and environmental impact fees and other hoops you had to jump through,” said Arendsen. “Now we can build an ADU in two weeks … then we can install it in two to four weeks.”

The units are generally small, but there’s a reason they’re in such high demand.

When Lynn O’Shaughnessy moved to La Mesa in 1991 with her then-husband and daughter, they used a small room in their garage as a temporary rental unit — a sort of makeshift ADU — and the rent helped pay off her mortgage.

After permitting got easier, she turned the whole garage into a bigger one bedroom with glass doors and big support beams across the ceiling in 2019. From the outside, it looks like a small guest house, and because it’s bigger and can be listed legally, O’Shaughnessy can use it as a rental or an Airbnb and command enough rent to supplement her income as a freelance journalist.

She admits watching La Mesa change is bittersweet. She also sees why it is necessary.

“Before I had this built I could understand why some of my friends were against the ADUs,” said O’Shaughnessy, who is 67. “But I think this is the kind of thing more people are going to need to get used to.”

At a certain point, though, changing something so ingrained as single-family zoning gets harder.

In 2021, the California Legislature ripped off the Band-Aid, passing two landmark bills — SB9 and SB10 — which, respectively, enabled as many as four units on a single-family lot and made it easier to build medium-density housing in key areas.

This time the reaction wasn’t so measured. Communities devised every imaginable workaround. (One particularly wealthy town near San Francisco declared itself a mountain lion habitat in an attempt to avoid zoning for duplexes.)

But California has amassed an arsenal of very real punishments for cities and towns that try to avoid housing rules — chief among them the threat of letting developers simply ignore zoning in defiant communities — and so most eventually went along.

It’ll take time for all that new zoning to result in actual homes, and San Diego remains one of the most expensive rental markets in the country. But over the last year, rents have edged downward, falling 1.4 percent, according to Apartment List.

“Is it working?” asked David Garcia, policy director for the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California Berkeley. “My very simple answer to that question is ‘Not yet, but maybe.’”

Advertisement

This sort of change in Massachusetts faces a tough road.

As soon as Healey announced her ADU push last month, prominent opponents countered that overhauling zoning from Beacon Hill was unacceptable.

Chief among them was the Massachusetts Municipal Association, which lobbies for cities and towns and has long been the state’s most powerful advocate for local zoning control. The organization said it supports ADUs, and has even crafted recommendations for local policy, but opposes statewide legalization on principle.

“We start this conversation with being opposed to preempting local zoning,” said executive director Adam Chapdelaine.

That stance is likely to resonate with legislators who hear it loud and clear from local officials and longtime homeowners in the towns they represent, and who have typically declined to take up any statewide housing reform.

Through 100 years of growth, decline, and growth again, the state has almost never stepped in to press municipalities to loosen rules and allow more housing.

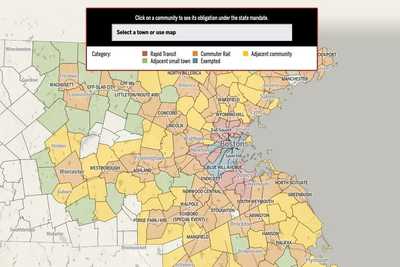

A rare exception came two years ago, when the Legislature passed the MBTA Communities Act, requiring towns and cities served by transit to designate some land for denser housing. It’s the most ambitious housing law Massachusetts has enacted in decades and it could open the door to tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of new homes.

But passing MBTA Communities took something of a political tightrope walk, not easily replicated. Then-Governor Charlie Baker — himself long an advocate of local control — was keen to tackle housing before leaving office and pushed a bill that would make it easier for communities to pass zoning changes.

Joe Boncore, a former state senator who was then chair of the Legislature’s housing and transportation committees, saw an opportunity. Baker’s bill had been added to a broader economic development bill, and Boncore managed to tack on the MBTA Communities provision in the closing hours of a COVID-delayed legislative session.

The Mass. Municipal Association was aghast and urged Baker to veto it; he declined. And enough legislators were brought on board to make it law.

“Everyone understood that the supply issues were the consequence of outdated zoning laws, too much local control, and that something needed to be done,” said Boncore. “But it’s another thing entirely to actually do something about it.”

To do something, that is, about the patchwork of town-by-town rules that serve more to squelch development than to speed it.

ADUs have been one casualty. Many municipalities allow them in some form, at least on paper. But a 2018 study by zoning researcher Amy Dain found that even the communities that do only produced an average of 2.5 per year — thanks to a thicket of rules and permitting that kill most proposals before a shovel hits the ground.

How does that work? Just ask Chris Lee.

Lee owns Backyard ADUs, one of the few companies that builds ADUs at scale in Massachusetts. He recently proposed an 840 square-foot backyard cottage in Concord, which allows ADUs by-right if they are 750 square feet or smaller.

Lee’s client wanted the cottage for their mother, so she could live nearby as her grandchildren grow up. It would go behind a sprawling house with a white picket fence and marble columns on a full acre of land, in a neighborhood full of big homes on spacious lots.

That additional 90 square feet meant the unit required approval from the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals and public meetings, where neighbors could object. Complaints poured in, from a Harvard-educated lawyer who lived next door, from a CEO, and from other neighbors who worried the building would be visible from the street and cause “substantial detriment” to their historic neighborhood. The ZBA delayed its vote for a month, then two. Lee and his clients were stuck in limbo.

“We’re talking about a small house in a backyard,” said Lee. “We have neighbors arguing over every minute detail. ... That’s why it’s so damn expensive to build in Massachusetts.”

Even harder to build is the kind of middle-density housing that other high-cost states are looking at and that was common in Massachusetts — such as the region’s trademark triple-deckers — until it was largely banned in the early 20th century.

Since then, Massachusetts has mostly built two kinds of housing: larger multifamily buildings big enough to withstand the costly permitting process, and single-family homes. Only 5 percent of housing built in Massachusetts in the 2010s came in the form of two-, three-, or four-unit buildings, according to a Globe analysis of Census data.

That has left behind a severe shortfall of new middle-income housing, the type that can free up older apartments that rent at lower rates.

There are basic economics at work here. One unit of smaller, middle-income housing is less expensive to produce than a single-family home on the same lot. Two years ago, Brookings Institution housing researcher Jenny Schuetz and the think tank Boston Indicators studied land use in four Greater Boston suburbs. They came away with what is perhaps an obvious finding: the denser a small development, the cheaper it is for people to live there.

In Wellesley Hills, they found, a single-family home on a typical lot cost around $1.9 million. Five townhouses on the same lot would be more expensive to build, but cost around $830,000 apiece.

That is still not cheap, but it is closer to attainable, Schuetz said, at least in a town where the median household income tops $225,000. In less-affluent suburbs where land is cheaper, the cost of building those units declines further.

“What we are missing from the market today is housing that you can build cheaper, that will naturally rent cheaper,” Schuetz said. “There is tremendous demand for this. And the main reason we don’t have it in abundance is because politically powerful suburbs have prevented its construction.”

That can change, as La Mesa shows.

The city has its own history of exclusionary zoning rules and has managed to balance its old-time charm — its downtown features an antique mall and an old service-station-turned-old-timey-diner — with finding places for more people to live.

But as San Diego has continued to boom, La Mesa is changing, getting younger and more liberal, home to more people like Colin Parent who are looking for homes to build a life there.

When Parent strolls that alleyway in La Mesa, there is a certain sense of pride in his voice.

“This,” he says, “is what a city should look like.”

Andrew Brinker can be reached at [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Illustrations by Guillaume Kurkdjian

People in and around Boston are being challenged, in ways never before, to address the region's unprecedented housing crisis. The Globe Spotlight Team probed this question and found yet another crisis: One of consensus and will.

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC