Beyond the gilded gate:

A BOSTON BUILDING,

SCATTERED SOULS, AND

RENT CONTROL REVISITED

The end of rent control three decades ago helped push many working people out of a Fenway apartment building — and out of Boston. Their stories speak to one of the causes of the current housing crisis, and to the increasing demands that rent caps return.

Boston

Nearly 30 years ago, Holly Bartel gazed up at the antique brass ceiling lamp in one of the best apartments she’d ever had in Boston, and thought: Yeah, I’m taking that.

“I borrowed a ladder and I freed it,” Bartel said recently of her sentimental theft, long after any statute of limitations had expired.

Over the past three decades, she has carried the lamp like a talisman to every place she’s lived. It is mounted today in her little house in Bellows Falls, Vermont, where she moved for a lower cost of living.

The keepsake from her old apartment building, then known as Hotel Hemenway, is a reminder of an exciting time in her life, when people like her, who did not make much money, could afford an apartment in Boston, right in the thrumming heart of city life.

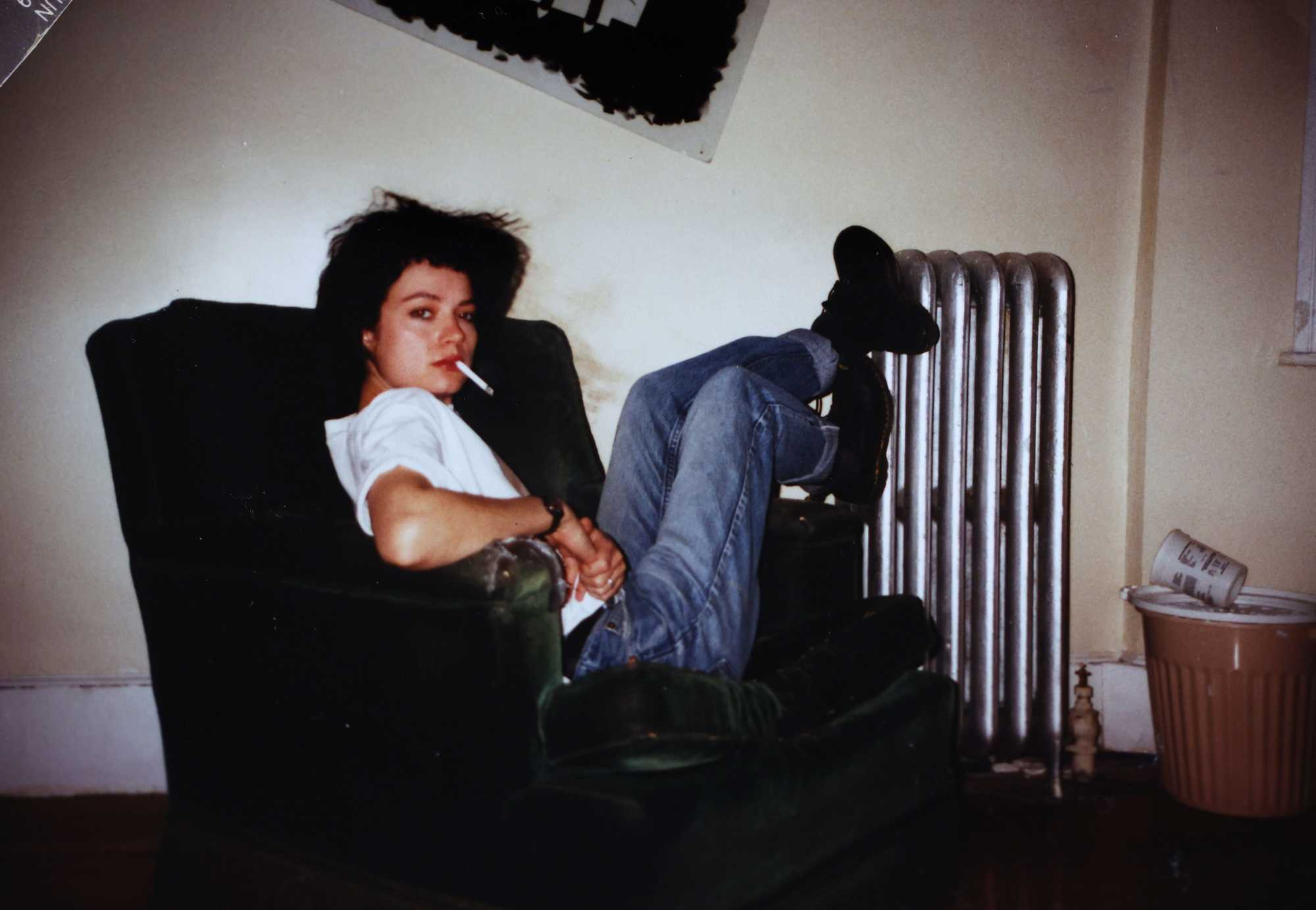

Holly Bartel in her Hotel Hemenway apartment in the early 1990s (left) and today, at her house in Bellows Falls, Vt. (Provided by Holly Bartel; Jonathan Wiggs/Globe Staff)

That was before the state voted in 1994 to abolish rent control, and sharply rising rental costs forced Bartel and dozens like her out of her beloved building in the Fenway neighborhood, and ultimately out of Boston. Back then, Bartel paid $561 for a one-bedroom, and when rent control ended, the landlord proposed to roughly double that amount for her unit, she recalled.

“I had a nice little apartment that was affordable, in a building with a really diverse mix of people, which describes the Fenway before rent control got voted out,” said Bartel, 63, one of a number of former tenants of that building whom The Boston Globe tracked down. “Then everybody left but the wealthy students and the upwardly mobile people.”

A one-bedroom unit in her old building recently listed for $3,400. Even after adjusting for inflation, that is still three times more than her old rent.

The story of the Hotel Hemenway is the story of a city transformed, and also of the state’s on-again, off-again history with rent control. And that story continues, with intensity, today. Twenty-nine years after Massachusetts voters ended rent control in a ballot initiative, there’s an escalating political battle over resurrecting government controls, a response to the region’s unprecedented housing crisis that has pushed costs out of reach for many working people.

“Everywhere across our city and region, people are at a breaking point when it comes to housing costs,” Boston Mayor Michelle Wu told the Globe.

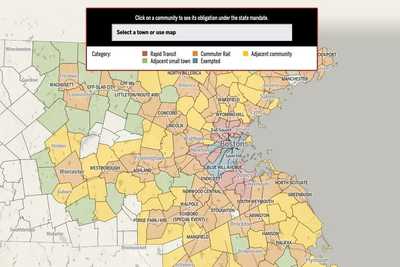

Wu has sent a home-rule petition to the Legislature seeking permission to limit rent increases under a formula tied to inflation, a more flexible version of rent control being adopted in other states and often called “rent stabilization.”

Wu’s plan has been met with fierce opposition by members of the real estate industry, who say Boston should instead focus on encouraging more housing construction. The mayor’s plan would limit annual rent increases to no more than 10 percent, with many units exempted from the cap, including newer construction and owner-occupied smaller buildings. Somerville City Council voted last week to seek a home-rule petition to regulate rents, and Brookline Town Meeting has asked its Select Board to do the same.

Meanwhile, with desperate renters demonstrating in front of the State House, lawmakers have filed bills to repeal the statewide ban, enabling cities and towns to adopt their own rent regulation without seeking additional permission from the Legislature.

Any of these initiatives would require state approval. And while polling indicates strong statewide support for rent control, legislative leaders have not yet shown the appetite for allowing municipalities to control rents.

Amid a broad search for solutions to Greater Boston’s housing crisis, the present and future fight over rent control in Massachusetts is, in part, about the past — about what was gained when government limits on rents were phased out starting in 1995, and what was lost.

Bartel lived for about five years in the early 1990s at the Hotel Hemenway, a stately, turn-of-the 20th century apartment building at 91 Westland Ave. Oh, those magnificent high ceilings, she recalled, and the shining hardwood floors. She had marble tile in her bathroom, along with the original clawfoot tub and pedestal sink.

All that old elegance made the building attractive. It was the tenants, however, who made it interesting.

They were a grab bag of creative types, former Hemenway tenants said. There were writers and artists, guitar strummers trying to make it as professional musicians, and a classically trained opera singer, who did. There were old hippies and eccentric characters — the hoarder who lived like a mole among piled junk, the male stripper and porn star who kept a pet boa constrictor.

Among these free spirits were retirees on fixed incomes — the former merchant mariner, the retired Avon lady — as well as blue-collar and service workers struggling to keep their nostrils above water at the lower end of the income pool: secretaries and salespeople, busboys and bartenders, handymen and hair stylists.

What they represented, together, was a Boston that no longer exists.

“Once rent control was gone, a lot of the families had to leave as well as the single people who didn’t have a lot of money,” Bartel said. “That’s a lot of musicians and artists. It’s like Boston just slapped all the interesting people in the face and said ‘get out.’ "

With demand for housing outstripping supply, and no caps on increases, rents have exploded. Massachusetts is one of the most expensive states in the nation for renters. To afford a modest two-bedroom apartment at $2,165 per month in the state, a renter would need to earn almost $42 an hour, or about $87,000 a year, according to a recent report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Only California and Hawaii are more expensive for renters.

In Boston, apartment listings often run much higher than that. The median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the city was at least $3,400 in early December, according to both Zillow and Zumper, which regularly gather such data. To afford that, a household would need an income of about $136,000 — more than twice the median income of Boston renter households, around $61,000, according to Census figures.

Rental costs are particularly daunting for lower-income households: Less than 1 percent of Boston’s advertised rental listings in 2021 were affordable to households making $50,000 or less, yet 48 percent of all Boston renters had incomes under $50,000, according to a city report. More than half of renters in Greater Boston are now “cost-burdened” by housing, spending over 30 percent of their income on rent — the highest rate in the last 17 years, according to a Boston Foundation report.

The eclectic mix of characters at the old Hemenway building is mostly gone, largely replaced by college students subsidized by their parents.

Bartel’s former landlord, Jeffrey Libert, still works at the company that manages the 152-unit building, now called the Parkside. Libert, 68, is chairman of the Cambridge-based residential property firm Forest Properties Management, and an affiliated company bought the old Fenway building in 1994.

Many landlords hate rent control with the flaming passion of a thousand suns, and Libert has opposed it in the past. In 2002, as then-president of the Rental Housing Association, representing owners and managers of more than 100,000 rental units statewide, he wrote a Globe op-ed criticizing a proposal to reinstate rent control and saluting new construction as “the best long-term solution to the need for more affordable rental housing.”

Back in the mid-1990s, the Parkside became a flashpoint in the city’s transition away from rent control, when Libert and a group of tenants tangled over rent increases.

“They picketed my house on my birthday,” Libert recalled of former tenants who showed up at his then-home in Newton. (Bartel, who was there, remembered that day more fondly than Libert does.)

Three decades after rent control was lifted, Libert agrees Boston has changed — but he says it’s gotten better.

“There’s been a lot of housing production, a lot of cranes in the sky, you can see them, adding apartments left and right,” Libert said. “From my perspective, it’s a much more exciting city than it was then. At that time, going down Westland Ave., you’d be seeing signs in windows, ‘Please don’t burn my building.’ That’s what the city was like then.”

Now, he said, a thriving economy and vibrant cultural scene make this a place where people want to be.

“If you really believe capitalism adds wealth and prosperity, which I strongly believe, you can see it working in Boston,” he said.

Advertisement

At the dawn of the 20th century, a stately Georgian revival brick building rose at an eastern gateway to Frederick Law Olmsted’s Back Bay Fens. The eight-story apartment hotel was built on reclaimed marshland in a new neighborhood soon filled with handsome institutional and residential buildings.

Advertised on postcards as “just a little different,” the building near Symphony Hall would become home to numerous classical musicians, including composer Igor Stravinsky for a time, and a future Massachusetts governor.

The building has been around for three major versions of rent control in Massachusetts. Over the decades, governments have imposed price controls on rents and other necessities, including utilities and insurance.

After World War I, with troops coming home and the economy in a recession, the state’s rental market was tight. Access to affordable housing became a political crisis. The Legislature responded in 1920 by passing bills to give tenants more rights, including protecting them from profiteering by prohibiting most annual rent increases of more than 25 percent. Some landlords took the law as an invitation to hike rents 25 percent a year, or evaded restrictions by pushing out tenants and jacking up costs on the next renter, a state analysis concluded. The law expired around 1923, the Globe reported.

During World War II, the Roosevelt administration feared inflation would wreck America’s war-supply production. To control rising costs, Congress in 1942 authorized the Office of Price Administration to set maximum prices for goods and services, including rents. Congress extended rent control to 1953, and Massachusetts lawmakers extended controls in-state through 1955. Governor Christian Herter, a Republican, vetoed additional extensions, the Globe reported at the time. “To shackle one segment of the economy while the other segments remain free is not justice for all,” Herter said in his veto message.

Fast forward to 1969. Boston rents had increased at the second fastest rate among major US cities over the prior decade. Residents in Cambridge that summer staged an elaborate “funeral” outside City Hall to mourn the lack of action on rent control.

“Some feel rent control is the only answer,” the Globe wrote in June 1969, “but the very mention of it brings forth bitter debate.”

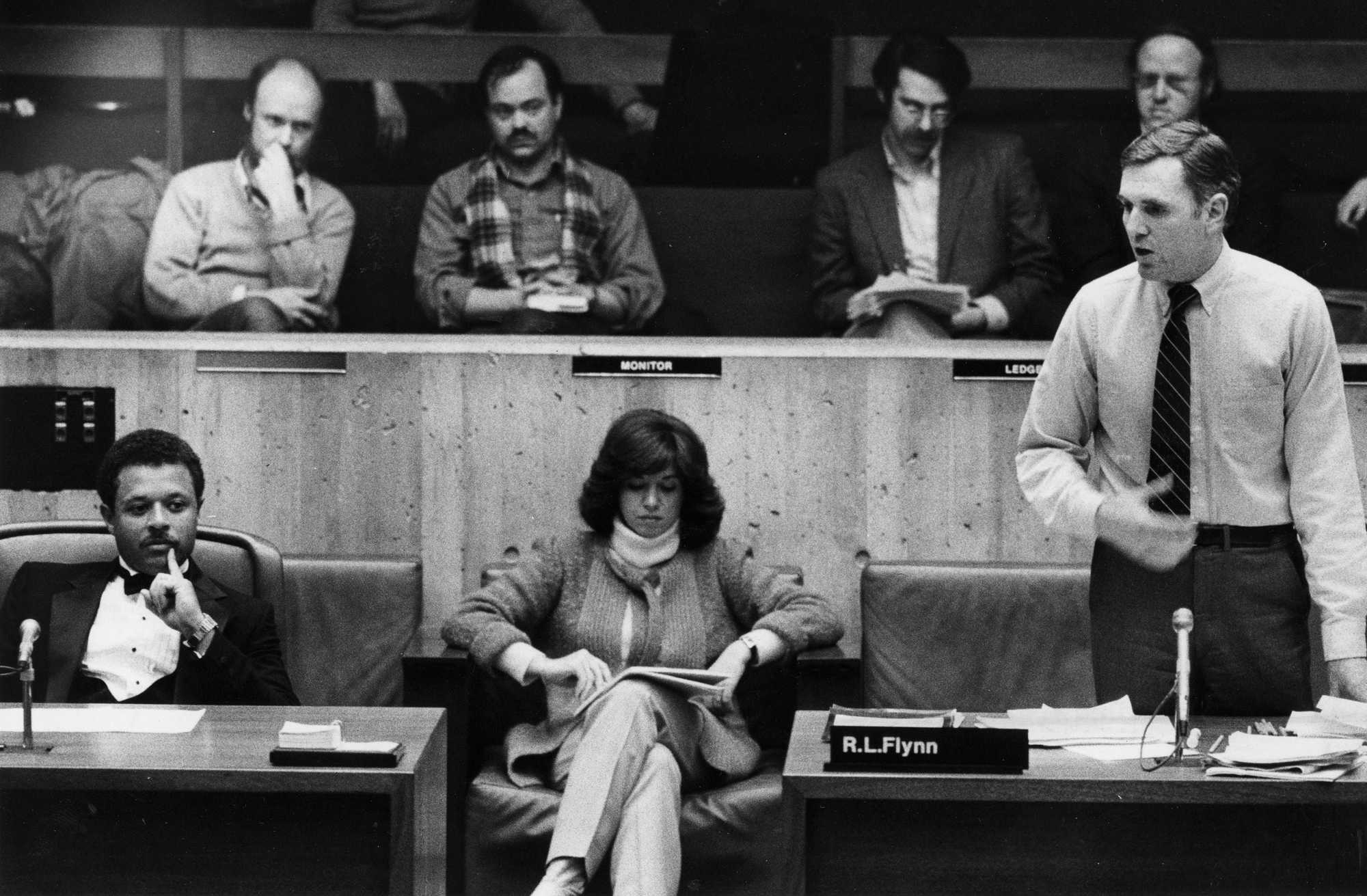

Boston Mayor Kevin White, a Democrat, pressed for permission to control rents, which the Legislature granted the city in 1969. The next year, Republican Governor Francis Sargent signed a series of bills to strengthen rent control in Boston and extend permission to control rents to more than 40 other communities, the Globe reported.

The early 1970s were an unsettled time of protests and social upheaval, and rent-control rules tilted strongly pro-tenant. Boston landlords were forced to justify rent increases individually to a municipal board. But by 1976, Boston was already transitioning away from stringent controls. The city instituted a “vacancy decontrol” policy that let landlords reset rents to market rate when tenants moved out.

Rent control was a contentious political issue in Boston until a 1994 statewide vote to abolish it. Left: On New Year's Eve 1982, members of the City Council, which included Ray Flynn (speaking), voted to extend the city's rent-control ordinances for 15 days after a dispute with then-mayor Kevin White. Right: A candlelight vigil supporting rent control at St. Paul's Cathedral on the Sunday before the November vote. (Janet Knott/Globe Staff, Kuni Takahashi for The Boston Globe)

By the 1980s, time had taken a toll on the Hotel Hemenway. It included dozens of single-room-occupancy units and sheltered an assortment of older tenants, workers, students, and artists who briefly set up a fringe performance space there. Drug dealing and prostitution in the area led the mayor’s office to order pay phones removed from outside the building, the Globe reported. In the early 1990s, the live-in superintendent even faced criminal charges himself, after police discovered at least 800 bags of heroin in his apartment, according to Globe stories.

William Fritzer, who moved to the Hemenway in 1984, loved the building for its characters. “There were all kinds of interesting people,” he said. He recalled an antiques dealer, numerous musicians, and an elderly woman who “got a little daffy” and fed the building’s mice.

"It was the deal of the century,” said William Fritzer, now a butler and house manager in East Hampton, N.Y., recalling his old loft space at Hotel Hemenway. Fritzer, who lived there from 1984 to 2003, outfitted the apartment's tall windows with elaborate curtains and maintained flower boxes outside his ground-floor unit. (Gordon M. Grant for The Boston Globe; William Fritzer)

Fritzer, who worked as a room-service captain at the nearby Marriott Hotel, Copley Place, also remembered how little he paid when he moved in: “The rent was $412, it was just fabulous,” said Fritzer, who had clouds painted on the ceiling of his one-room loft. That’s the equivalent of about $1,240 today. “All utilities were included; that’s what made it so sweet living there. It was the deal of the century.”

Rob McCausland, now 71, fondly remembers the views from his high-floor Hemenway apartment in the 1990s. “In terms of the tenants, we were like a collection of family,” he said.

Part of that family, Kevin Maloney and his partner, Barry Adams, arrived at the Hemenway in early 1994, attracted by its beautiful architecture, gay-friendly atmosphere, and diverse mix of residents. But certain things couldn’t be ignored: “There were streetwalkers at night along the perimeter of the hotel,” Maloney said, as well as syringes sometimes left in the elevator.

Libert’s company bought the building in September 1994, during the campaign leading up to the rent-control repeal vote.

By then, just Boston, Brookline, and Cambridge maintained any form of rent control in Massachusetts. Still, the Massachusetts Homeowners Coalition promoted a ballot question to ban it statewide.

In the campaign that followed, rent-control opponents focused on Cambridge, which had the strictest policy. A sizable majority in the three communities with rent control wanted to keep it, but the state result took rent control away. The abolition passed statewide, 51 percent to 49.

Rent control in Massachusetts was dead yet again, though it never seems to stay that way.

Advertisement

The way Jeffrey Libert remembers it, the old Hotel Hemenway needed to be rescued.

“Why did I want to buy it? It was a blight on the neighborhood, and I felt I could turn that property around,” said Libert during an interview at the headquarters of Forest Properties, the family company he started decades ago. The building was hurting nearby properties in his portfolio, he explained.

There was a mountain of work to do. “The building itself was in deplorable condition,” he said. “There was so much drug-dealing taking place there, when we put a doorman in the building, the company that supplied the doorman called back the next night and said, ‘We won’t put a doorman there without a gun.’”

Libert, now semi-retired, recalled many residents were happy with Forest Properties’ improvements.

It is difficult to quantify how much Massachusetts property owners overall benefited from rent control’s demise. According to a study of Cambridge by MIT economists, eliminating rent control increased the value of that city’s residential real estate by about $2 billion between 1994 and 2004, a boon for property owners and city tax coffers.

Libert’s investment in the Parkside certainly paid off: The building’s assessed value is now more than $28 million, seven times higher than when he bought it. It has produced millions in revenue for his firm, which has about 125 employees and manages around 500 apartments in Boston and 5,200 elsewhere along the East Coast.

One reason Libert’s firm diversified outside Boston, he explained, was the threat under former mayor Thomas Menino that rent control might return. “Why do you want to be in a place where there’s this shadow or clouds over your head all the time?”

Libert said his company provides housing for “middle-class people. They’re not the super rich.” As of last year, his buildings’ cash flow was two times debt service, he said, so if there’s a recession, “we have a lot of cushion for bad things to happen.”

Bartel remembers the letter slipped under her apartment door, not long after the rent-control vote, she said. She was an administrative assistant at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at the time.

The note said her rent would roughly double, she said. “I can’t even tell you what I said at that moment because you would not be able to print it.”

In response to the rent increases, some of which were much lower, members of the Hemenway Tenants Association took action, led by a Unitarian minister and political agitator named Susan Starr. “She was an old-time rent activist from Oakland,” Maloney, the former resident, recalled. “So she knew how to mobilize people. And she was the one who mobilized us.”

The Globe tried to locate Starr, knocking on doors in Acton, where records suggested she had once lived. Ultimately, Starr’s former sister-in-law said she had moved to Mexico, then died in 2018. “She practiced activism almost as an occupation for most of her life,” Andrea Starr said.

The Hemenway Tenants Association deployed various tactics to pressure Libert’s firm and buy time. Some tenants threatened with eviction went to court, and many of them were represented by lawyer Robert Shapiro.

“The tenants were no better than in other buildings, and the landlords were no greedier or worse, I don’t think,” Shapiro recalled recently. “It was a pure economic fight.”

Ultimately, a deal was struck. Some elderly tenants were allowed to stay without major rent increases, and Libert’s company paid settlements to members of the tenants association to move out.

Residents scattered to the four winds. Maloney, a civil engineer, now lives in Tucson with Adams. McCausland, who is retired, lives in Virginia Beach, Va. And Fritzer, who loved the building so much he didn’t leave until 2003, works as a butler and house manager in East Hampton, N.Y.

Bartel, who left earlier, said she got a settlement of roughly $5,000. She moved to California, then back to Boston before decamping for Vermont around 2015.

“I could see the Boston housing market would price me out,” she said.

Most US states ban rent control. But steep price increases in recent years have brought a drumbeat of calls to embrace it anew, often in coastal states with high rents and progressive politics.

Rent regulation is now in effect in around 200 jurisdictions in seven states: California, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon, as well as Washington, D.C.

Rather than freezing rents or imposing inflexible low caps, many newer programs tie rent increases to inflation. Many policies also exempt new construction to avoid discouraging development.

Mayor Wu’s plan is considered relatively modest in scope, though it is still opposed by the real estate industry. It would limit annual rent increases in Boston to 6 percent plus inflation, up to 10 percent. It would cover about 55 percent of Boston’s rental units, according to city data, with exemptions for properties including owner-occupied buildings with six or fewer units and any new construction for the first 15 years. Between tenancies, landlords would be free to raise rents as much as they want.

“Every single day,” Wu told the Globe, “whenever I ask our residents what’s on their minds, housing is at the top of the list.” She cited seniors “worrying about how to stay close to the communities they helped create” and “young families who are slapped with a sudden, egregious rent increase and are frantic, having nowhere to go.”

Economist and housing specialist Barry Bluestone, professor emeritus at Northeastern University, called Wu’s proposal “as close to the perfect rent control bill as possible. It should not have any impact on new housing construction, but it would possibly reduce some of the dramatic increases in rents.”

It’s an “anti-gouging” plan, said Chris Herbert, managing director of the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, noting that “it does protect tenants from displacement because of astronomical increases in any one year.”

Yet the proposal has taken flak from both sides.

The Boston community organizing group City Life/Vida Urbana has been working to build support for rent control for years. Mike Leyba, its co-executive director, said the city’s bill isn’t strong enough. “We didn’t feel like it was meeting the need or meeting the moment,” he said.

Annual rent increases of up to 10 percent would be too much, he said. For someone paying $2,500 a month, rent could rise $3,000 in one year. A more reasonable cap would be 3 percent, as in some other states, he said.

Meanwhile the Greater Boston Real Estate Board, a trade group that launched a six-figure campaign against rent control this year, argues that it generally inhibits housing production, discourages apartment maintenance, and drives down tax revenue.

MassLandlords, a trade association for property owners and managers, is concerned that Boston’s plan would permit an unelected municipal board to deny some rent increases based on tenant complaints, said Douglas Quattrochi, the group’s executive director.

And many individual landlords are deeply suspicious of any form of rent control, seeing it as a slippery slope. Libert described Wu’s plan as “very gentle.” The trouble is, he said, “It’s like a Trojan horse. They could start putting in more regulation over time. That can happen.”

Designing a rent control program

Here are some of the main factors localities consider

CHOICE OF RENT CAP:

First-generation rent control programs imposed severe rent ceilings. Newer programs typically limit annual rent increases to a certain percentage, often tied to inflation, sometimes with a maximum cap. Oregon, which capped rent increases at 7 percent plus inflation, saw rents soar early this year before adjusting its plan to cap total increases at a maximum of 10 percent.Advertisement

The former Hotel Hemenway — the Parkside — is a very different building now than during rent control. For one thing, a 268-square-foot studio, smaller than two parking spaces, was recently listed at $2,550 a month.

For another, the Parkside is now dominated by college and grad students, a population that floods the housing market each fall and is often blamed for squeezing out other residents and pushing up prices.

Some students living there are just as gobsmacked by high rents, saying they only manage with the aid of family.

“Oh my God, it’s insane,” said Alejandra Floripe, 21, a Suffolk University psychology student who pays $2,200 a month for a studio apartment. “I get help from my godparents and my parents.” According to a Parkside leasing agent, a student renter must have a cosigner with an income four times the annual rent. In Floripe’s case, that’s over $100,000.

Resident Jack Walsh, 24, a Northeastern graduate student in journalism, said he has financial help from his mother and grandparents. His one-bedroom costs $3,000 a month. “I don’t know anyone my age who can pay $36,000 a year,” he said.

Like many apartment buildings around Boston, the Parkside is marketed as “luxury,” though there are few frills. The bones of the grand old hotel may be intact, but some surfaces are faded and showing their age. (Libert said the hallways are getting new carpets, lighting, and paint next year.)

“This isn’t a modern building. It’s a convenient building,” said Walsh, whose apartment includes a galley kitchen and a view of the Fens.

The 27 colleges and universities that attract students to Boston provided less than half the housing needed to accommodate them in 2022, according to a city report. Over 38,000 students lived off-campus — and not at home — in Boston last year, the report said.

The effects are evident at the Parkside, a short walk from Northeastern, Berklee College of Music, and Boston University, the three Boston colleges with the largest numbers of undergraduates living in private housing.

The building, like much of Boston, has become a place for people of means.

“Boston, New York, and San Francisco have become ginormous resort economies,” said Shapiro, the tenants’ former lawyer. “What do resort economies do? They either provide affordable housing for people who clean hotel rooms, or they have them live 30 miles away and they commute in and commute back.”

Eventually, he said, you end up with just the richest people living there.

“That makes for a boring community, and a boring world.”

Reporters on this story can be reached at [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Beyond the gilded gate

People in and around Boston are being challenged, in ways never before, to address the region's unprecedented housing crisis. The Globe Spotlight Team probed this question and found yet another crisis: One of consensus and will.

Preview: Data

Graphics: Why it’s so hard to afford housing in Boston

Part 1: Milton

In towns like Milton, home prices are a threat to prosperity. But they don’t have to be

Map

How will the state’s historic rezoning mandate affect your community?

Part 2: Generations

One house, one family, and the fading dream of homeownership

Part 3: Luxury towers

Reckoning with Boston’s towers of wealth

Part 4: Brookline

An identity crisis comes to Brookline

Part 5: Single-family zoning

Reimagining an American ideal

Part 6: The renters

A Boston building, scattered souls, and rent control revisited

Part 7: Construction costs

The $600,000 problem. Why does it cost so much to build housing in Boston, and what can we do about it?

Calculator: Construction costs

Calculator: Penciling out a project

Credits

- Reporters: Mark Arsenault, Andrew Brinker, Catherine Carlock, Stephanie Ebbert, Diti Kohli and Rebecca Ostriker

- Editors: Patricia Wen, Tim Logan, Mark Morrow

- Photographers: Lane Turner, Jessica Rinaldi, Erin Clark, Craig F. Walker, Pat Greenhouse, David L. Ryan, Jonathan Wiggs

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and Bill Greene

- Video producers: Olivia Yarvis, Randy Vazquez, and Dominic Smith

- Video director: Anush Elbakyan

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development, graphics, and data analysis: Daigo Fujiwara

- Development: John Hancock, Andrew Nguyen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanac and Jenna Reyes

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC