Beyond the gilded gate:

Brookline broadcasts an ethos of inclusivity, but it has become a preserve for the privileged. This is no accident, but the fruit of decades of exclusionary actions. Now facing a state mandate to allow more multifamily housing, Brookline faces a choice: What kind of town does it want to be?

AN IDENTITY

CRISIS

COMES TO

TOWN

Brookline

Brookline has always considered itself special. And, in many ways, it is.

Originally a rural retreat for Massachusetts’ ruling class, the town sprang to life when a Gilded Age speculator brought a trolley line to Beacon Street and invited famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to transform what had been a country lane into a fashionable boulevard.

Then as now, convenient transit was a draw. Brownstones and apartment buildings rose up to accommodate early commuters, and generations of young professionals followed. With three branches of the Green Line, Brookline became a streetcar suburb like no other, providing easy proximity to the region’s top colleges, hospitals, and the Financial District.

It is a vibrant and varied community, one that broadcasts an ethos of inclusivity: Outside Town Hall, a rainbow-striped crosswalk leads to a “Black Lives Matter” sign so enormous, it might be the name of the building.

But the town’s history on zoning has long broadcast a very different message — one of exclusion. Brookline has become a preserve for the privileged, with homes priced out of reach for many who want to live here, including children raised in town and hoping to make their adult home here and many of its municipal employees. Housing built to be affordable is also in short supply; the local inventory fell slightly below the 10 percent threshold set by the state anti-snob zoning law for part of this year.

And, notwithstanding that big Town Hall sign, there are comparatively few Black people who live in Brookline — just 2.5 percent of the population. That is the second-lowest percentage of any community that borders Boston — and Brookline doesn’t just border Boston; it is enveloped by the city.

Brookline, like many suburbs, has been fending off multifamily housing construction for decades, exacerbating a regional housing shortage that has spiraled out of control, with many more jobs created than houses built. That puts huge upward pressure on prices, which have far outstripped the means of most buyers. It’s an opportunity gap with deep roots and far-reaching economic effects — a crisis hard for existing homeowners to feel, much less worry about, as their own properties grow ever more valuable. The journey on Zillow seems only to go up.

In Brookline, a town of about 63,000 residents, data show that residential construction plunged 50 years ago, after residents balked at the density of new apartment complexes being developed and dialed back height limits for new buildings.

In the ensuing decades, those who already lived in Brookline effectively kept others out by creating historic preservation districts, filing lawsuits against developments, and endorsing zoning changes that limit growth and preserve value.

This sort of exclusionary playbook has been used throughout much of Massachusetts, where home prices have risen faster since 1980 than in any other state. The median selling price for single-family homes in Greater Boston climbed to a record $910,000 in July, according to the Greater Boston Association of Realtors. That would barely buy a condo in Brookline, where the median price hit $927,500 this summer. For single-family homes, the number was more than double that — $2.5 million, data from The Warren Group show.

Brookline offers a striking case study in the depth of suburban resistance to change. But it is no cookie-cutter suburb. The northern part of Brookline has a decidedly urban feel, filled with apartment buildings built decades before the town reined in housing development. Though its southern portion is dominated by luxe mansions and lush lawns, this is the rare suburb that has more multifamily units than single-family homes. Brookline also stands out nationally for its liberal reputation, with leaders often making pronouncements related to climate change and social justice.

It is, in short, the kind of community one might think would welcome a historic new state law requiring more multifamily homes to be allowed near transit lines to help relieve the region’s dire housing shortfall. But over the past year, the state law has spurred intense resistance in Brookline as in some other towns facing the same pressure. Opponents here resented both the imposition of a rigid mandate by the state and its judgmental implication: That Brookline, no ordinary suburb, is part of the problem.

“We have mad, mad, crazy amounts of multifamily housing. We’re not Sprawlsville,” said Linda Olson Pehlke, a resident and urban planner who led much of the early opposition.

“We have mad, mad, crazy amounts of multifamily housing. We’re not Sprawlsville.”—Linda Olson Pehlke, Brookline resident and urban planner

A competing faction of housing advocates is pushing for Brookline to welcome as much housing as possible. One of their rallying cries: Many of the people who protect and serve Brookline can’t even live here.

The local schools are a well-earned source of pride, but then there’s this: Only 14 percent of Brookline teachers live in town, according to municipal data provided to the Globe. The median salary of a public school educator doesn’t come close to what homeownership in Brookline demands.

Similarly, only 21 percent of Brookline’s police officers and 22 percent of firefighters reside here.

Not even the fire chief lives in Brookline.

“I would have moved to Brookline if it was economically viable,” said John F. Sullivan, who lives in Worcester, where he worked for three decades. When he took over as chief in 2018, Sullivan recalled, only one of Brookline’s department heads lived in town, and that was someone who had inherited a family home.

Struck by the changing demographics, many renters and young parents are pushing Brookline to be part of a regional housing solution by embracing more development at all price points to alleviate demand. Those advocates have been showing up to enthusiastically support proposals at zoning meetings and offer a seldom-heard “yes-in-my-backyard” message.

Their intense, coordinated campaign has led to a potential compromise with the opposing side that, if it holds, could lead to hundreds of new housing units in the years to come.

With a key town vote expected as early as this month and a state deadline at the end of this year, Brookline has become a litmus test of suburbs’ willingness to help reckon with the regional crisis.

“I know that the world is watching Brookline,” said Judi Barrett, a planner who consults for the town.

Advertisement

A history of exceptionalism

An air of exceptionalism has always hung over Brookline, a suburb described as “an island of privilege surrounded on three sides by Boston neighborhoods” in one book chronicling its development.

“Brookline had a sense of its otherness, its specialness, from really the late 18th century onward,” said Keith N. Morgan, lead author of “Community By Design” and a Boston University professor emeritus.

Brookline refused to be annexed by the city of Boston 150 years ago this year, distinguishing itself from Roxbury, Dorchester, Charlestown, Brighton, West Roxbury, and Jamaica Plain. That left the town an island of Norfolk County floating between Suffolk and Middlesex counties. On the map, it makes no sense, but the town chose to remain apart.

One of the nation’s first streetcar suburbs, Brookline was early on dubbed the “Garden of Boston,” and “the richest town in the world.” Olmsted, who designed Central Park and Boston’s Emerald Necklace, was among the wealthy notables who set down roots here, along with his friend and collaborator Henry Hobson Richardson, the architect who designed Boston’s Trinity Church; art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner; and financial publisher Henry V. Poor — the “P” in Wall Street’s “S & P.”

Harvard Street was built as “the road to the colleges,” and the town has always attracted intellectuals and academics. Today, educational attainment is so high here that a bachelor’s degree is just an appetizer. More than 40 percent of residents over 25 have master’s or professional degrees (like M.D.s and J.D.s). And over 16 percent hold PhDs – a share higher than any community in the state, except the college towns of Amherst and Williamstown, according to census surveys.

For all of its prosperity, extreme inequality was evident early on in Brookline, as were exclusionary tactics. One of the nation’s earliest examples of a racially restrictive covenant comes from an 1855 deed for a property near the Longwood Mall, a park near the Riverway, that prohibited the buyer from renting it to tanners, butchers, “negroes,” or “natives of Ireland.”

In the early 20th century, after the state permitted communities to do so, Brookline joined many Greater Boston towns in banning triple-decker wooden homes — that trademark New England structure so often occupied by poor immigrants. The campaign against triple-deckers was led by anti-immigrant Brahmins like Joseph Lee and Prescott Farnsworth Hall, a Brookline resident who cofounded a national group called the Immigration Restriction League, which condemned the mixing of races and the influx of immigrants they deemed racially inferior.

Hall also led the Brookline Civic Society, the group credited in historic records for petitioning the town to adopt a zoning code in 1922. Two years later, Town Meeting unanimously voted to create a district where only single-family homes would be permitted. It encompassed most of the town’s acreage.

By then, many of Brookline’s apartments had already been built and the gatekeepers of good taste were trying to ward off other urban incursions. A movie theater, then considered risqué, was repeatedly rejected by town leaders and by voters. The Brookline Chronicle predicted in 1915 that with the influx of moving pictures, “the future of these streets will be doomed.”

It would take over two decades for Brookline to accept a local theater, which opened in a former Universalist church in 1933. Now, the Coolidge Corner Theatre is widely viewed as a regional treasure.

Advertisement

Residents halted apartment construction

The full arc of America’s approach to middle-class housing – from embrace to abandonment – can be neatly told in the story of one postwar housing development in Brookline called Hancock Village.

Construction of moderate-cost housing flourished in the years immediately following World War II, as communities tried to accommodate returning veterans and their families — the famous Baby Boom.

Hancock Village sprang from a partnership the town of Brookline formed with John Hancock Insurance Co. Built between 1946 and 1949, the garden-style development of 789 units stretched into West Roxbury and was marketed to veterans at below-market prices.

Six decades later, the appetite for low-cost housing had passed. The town of Brookline rebuffed a developer’s proposal to expand Hancock Village by building more townhouses and an apartment building. Fierce opposition came not just from neighbors, but from the town Select Board, which joined residents in fighting the project in court.

What had changed during those decades? Plenty.

Urban renewal had plowed down two entire neighborhoods of Brookline in the 1950s and 1960s, demolishing tenements to make way for modern buildings including Town Hall, the sprawling Brook House condominium complex, and public housing developments. The early 1970s brought a surge of proposals for apartment buildings such as Dexter Park, a nine-story complex of over 400 units in the Coolidge Corner area that residents tried to block.

Rattled by the pace and scale of the changes, Brookline Town Meeting members voted to scale back apartment density in 1973. First, they temporarily banned construction of buildings with six or more units, while notably exempting public housing. Then they imposed strict height limits and design review standards along the town’s main corridors, where the largest apartment buildings were being built. At the same time, they reduced maximum building heights in “local” districts along Harvard Street. They also decided that no multifamily buildings with 10 or more units could be built anywhere in Brookline without a special permit.

Those decisions instantly stunted residential growth around the town just as tumultuous societal changes, propelled in part by the Civil Rights Movement, were reshaping the development patterns of cities and suburbs. Boston would soon erupt into violence over court-ordered busing to integrate schools, and white flight to the suburbs would accelerate.

Brookline’s effort to squash apartment construction within its borders 50 years ago was remarkably successful: Only about 3,700 housing units have been built since then, assessing records show. In comparison, Brookline saw far more robust development in the previous decade, building about the same number of units in just 12 years.

Today’s pro-housing activists look back at the restrictive zoning decisions made 50 years ago with a jaundiced eye.

“While the folks who downzoned Brookline in 1973 did not draw a race-based red zone ... they clearly wanted to make it difficult for anyone new to move into this community,” Katha Seidman, a board member for the pro-housing group Brookline for Everyone, said at a public hearing in September.

Fast forward to 2011, when the owner of Hancock Village proposed a major expansion, including an apartment building with some affordable units. Neighbors were adamantly opposed, citing concerns about increased traffic, more students for the already crowded elementary school, and the need to protect a nearby nature preserve.

Apartment complexes — so common in the northern part of Brookline — are an anomaly in the southern portion of the town, below Route 9.

South Brookline is zoned almost entirely for single-family homes, in some spots with minimum lot sizes of 40,000 square feet. The neighborhood is characterized by open space, country estates, and golf courses, notably The Country Club, one of the first and most exclusive golf clubs in the nation.

When residents of South Brookline wanted to stop the expansion of Hancock Village, town leaders took an ironic tack: They exalted it as an example of a postwar housing development so unique it should be preserved as historic and protected from change.

Brookline Town Meeting crafted a bylaw that would allow the town to create so-called Neighborhood Conservation Districts. Then, Town Meeting members voted to create such a district around Hancock Village, limiting future changes to the landscape and capping building heights at 2.5 stories.

The developer, Chestnut Hill Realty, fought back and returned with an even larger plan that included more affordable housing units. Even after some town leaders negotiated a compromise, Town Meeting members voted it down.

It was a protracted legal battle, which the town ultimately lost. Four years ago, a Massachusetts Land Court judge invalidated the Hancock Village Neighborhood Conservation District, calling it “impermissible spot zoning” that was clearly designed to block the development.

Hancock Village got its permits. Much bigger now than when it was first proposed, the development will add 461 units, including a six-story apartment building called Puddingstone.

With 250 apartments, Puddingstone won’t be the largest building in Brookline. There were already 28 residential complexes in town with 100 or more units. But it’s the largest built in this century. Except for Hancock Village, Brookline hasn’t permitted a project with 100 units or more since 1984.

Advertisement

The anti-change Town Meeting

The tradition of local control over zoning has tended to empower opponents of new apartments and condos in Brookline and beyond.

A few years ago, Boston University researchers published a study documenting what was anecdotally evident to anyone who has ever attended a zoning board meeting: Development proposals draw overwhelmingly negative feedback. They concluded this by tracking public participation in planning and zoning board meetings in 97 Massachusetts cities and towns.

“While voters in these towns supported affordable housing construction in the abstract,” the researchers wrote, a significant majority of those attending meetings opposed specific project proposals.

In many Massachusetts towns, residents can do far more than voice their complaints at zoning meetings. They can cast deciding votes against housing proposals.

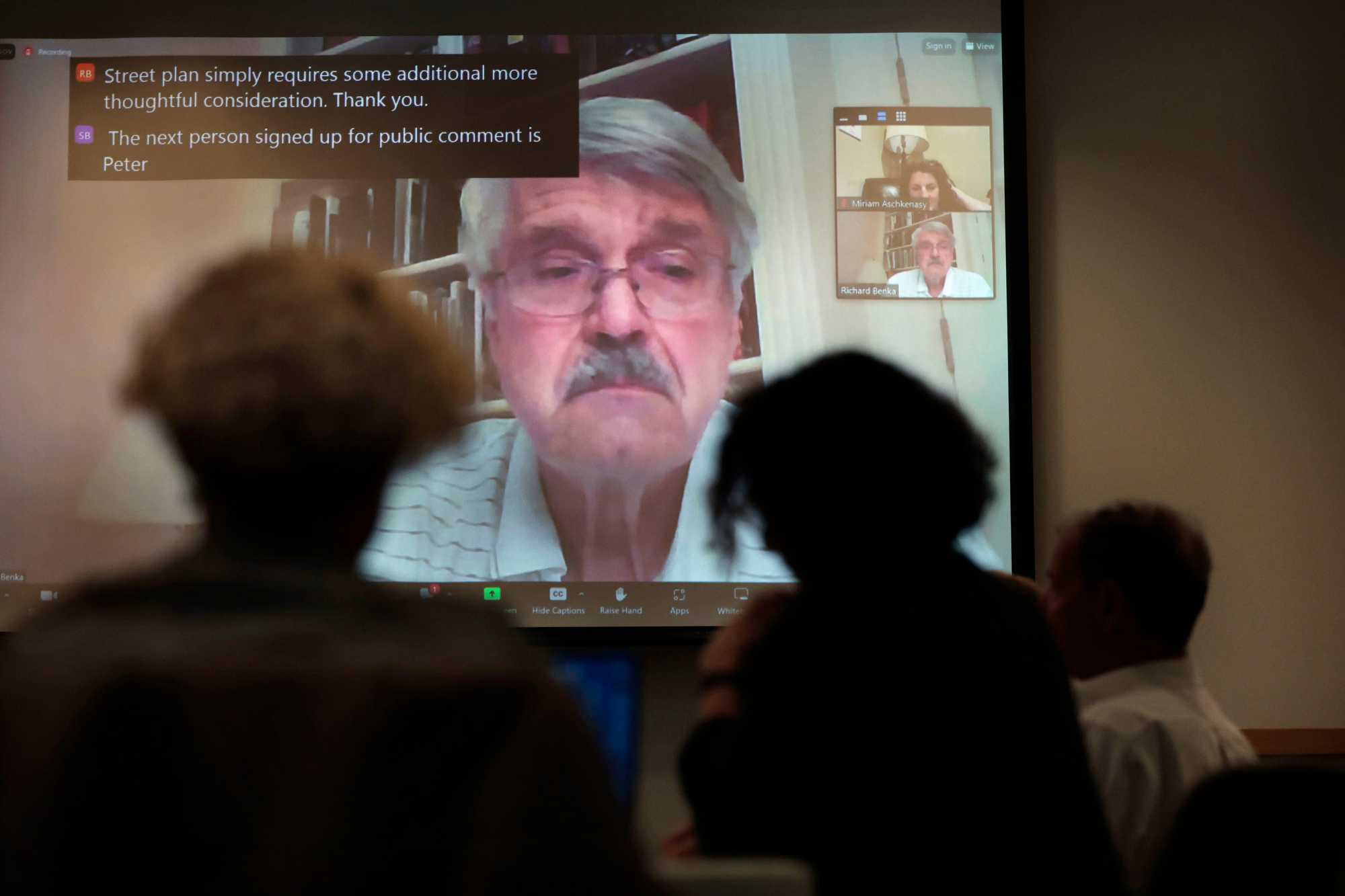

At a September public hearing, Select Board member Michael Sandman, left, talks with David Pollak, a member of a committee studying Brookline's rezoning efforts, as Select Board Chair Bernard Greene and members John VanScoyoc and Paul Warren prepare for the session to start. Richard Benka, shown on Zoom, later addresses the hearing. After many residents opposed Brookline’s initial rezoning plan, the Select Board appointed Benka to head a committee to come up with an alternative. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Town meeting, that quintessentially New England form of deliberative democracy, has the final say in town zoning changes, giving participating citizens hyper-local control over land use. Most Massachusetts towns have an open town meeting, where any resident can show up and vote. Brookline has a representative town meeting, which requires members to run for election to participate.

Town meeting is often viewed as the truest form of representative democracy. But the 255 members of Brookline Town Meeting are dramatically unrepresentative of the town’s population on two points — age and levels of homeownership, a Globe review found.

After the election in May, the median age of Brookline Town Meeting members was about 60 — far older than the median age of all Brookline residents, which is about 35. Though Brookline’s population skews young — with 30 percent millennials — only about 13 percent of Town Meeting members are millennials or younger. A majority of Town Meeting members, nearly 55 percent, are either baby boomers or members of the generation before them, the Globe review found.

Most strikingly, in a town where more units are rented than owner-occupied, the people elected to Brookline Town Meeting are overwhelmingly homeowners, the Globe found. Eighty-five percent of Town Meeting members own their own homes or live in properties owned by their spouse, partner, parents, or other relatives. Only about 15 percent of Town Meeting members are renters, the Globe found.

That concerns housing activists, who worry that the town leaders who control the valve of the housing supply through zoning have a vested interest in closing it.

“They have acted, time and time again, to keep supply low so that their property values go up and up and up,” said Amanda Zimmerman, a 40-year old neuroscientist and mother of three who cofounded Brookline for Everyone.

Or, as former Select Board member Raul Fernandez described Town Meeting: “It’s a homeowners association with a few renters.”

Advertisement

The limits of inclusivity

Brookline residents will be the first to tell you that they support affordable housing. And, by some measures, they really do.

Brookline has an “inclusionary zoning” policy that requires developers of four or more units to set aside 15 percent of them as affordable. The town is home to a significant number of public housing units built by the state and federal governments decades ago and has directed local funding toward much-needed renovations to keep them open. The town even built an affordable housing development on Fisher Hill, a picturesque neighborhood designed by Olmsted where the earliest settlers signed deeds with covenants promising to never allow apartment houses in.

But these few compromises have only produced a smattering of affordable units compared to all the high-end housing here.

From 1990 through 2020, Brookline added 8,473 people and just 2,608 housing units, according to data from the federal Census. Brookline’s housing inventory increased 10.3 percent during that time. Predictably, the median price of a home skyrocketed — 459 percent.

For people like Chima Ikonne, a 45-year-old father who teaches in Brookline, the local housing market has proved to be impossible.

“They have acted, time and time again, to keep supply low so that their property values go up and up and up.”—Amanda Zimmerman, neuroscientist and mother of three

“You put in an offer, you’re competing with people who … are willing to pay cash for everything, willing to offer $20,000 over asking,” he said. “These are people I can’t really compete with.”

Meanwhile, a community that prides itself on diversity is changing. Though its Asian, Latino, and multiracial numbers are on the rise, Brookline’s Black population has declined from 3.4 percent in 2010 to 2.5 percent in 2020, data show, and there is a $50,000 gap in median household incomes between white and Black households, the Brookline Community Foundation found.

A recent report from the Partnership for Financial Equity and the Chicago-based Woodstock Institute documented how very few Black homebuyers there are in town. Of the 575 buyers who got residential mortgages in Brookline in 2021, only 11 of them were Black.

A penchant for preservation

The preservation instinct is especially acute in a place as steeped in history as Brookline, the birthplace of President John F. Kennedy.

The Beals Street house where Kennedy was born was preserved as a national historic site after his death and restored to look as it had in 1917. Even today, his name is often summoned to ward off change to the neighborhood.

Six years ago, one resident unsuccessfully beseeched the town to preserve an out-of-use gas station from being replaced by housing, calling it an example of the architecture of Kennedy’s childhood. “The building at 455 Harvard Street is a quaint, early gas station – probably used by the Kennedys for their new motorcar,” she wrote, without providing evidence.

Reverence for Kennedy was most famously leveraged by Brookline residents who tried to preserve the shuttered church where he was baptized from being demolished for affordable housing.

St. Aidan’s Catholic Church was in a leafy but already dense neighborhood about halfway between Boston University and Coolidge Corner.

Still, neighbors erupted with opposition in 1999 when the Archdiocese of Boston proposed replacing the closed church with a six-story, 140-unit apartment building. Few of the opponents were parishioners, the Globe reported at the time. But their sophisticated efforts included outreach to the Vatican, hiring an expert in canon law, pleading for the creation of a historic district, and, eventually, filing a lawsuit in Superior Court.

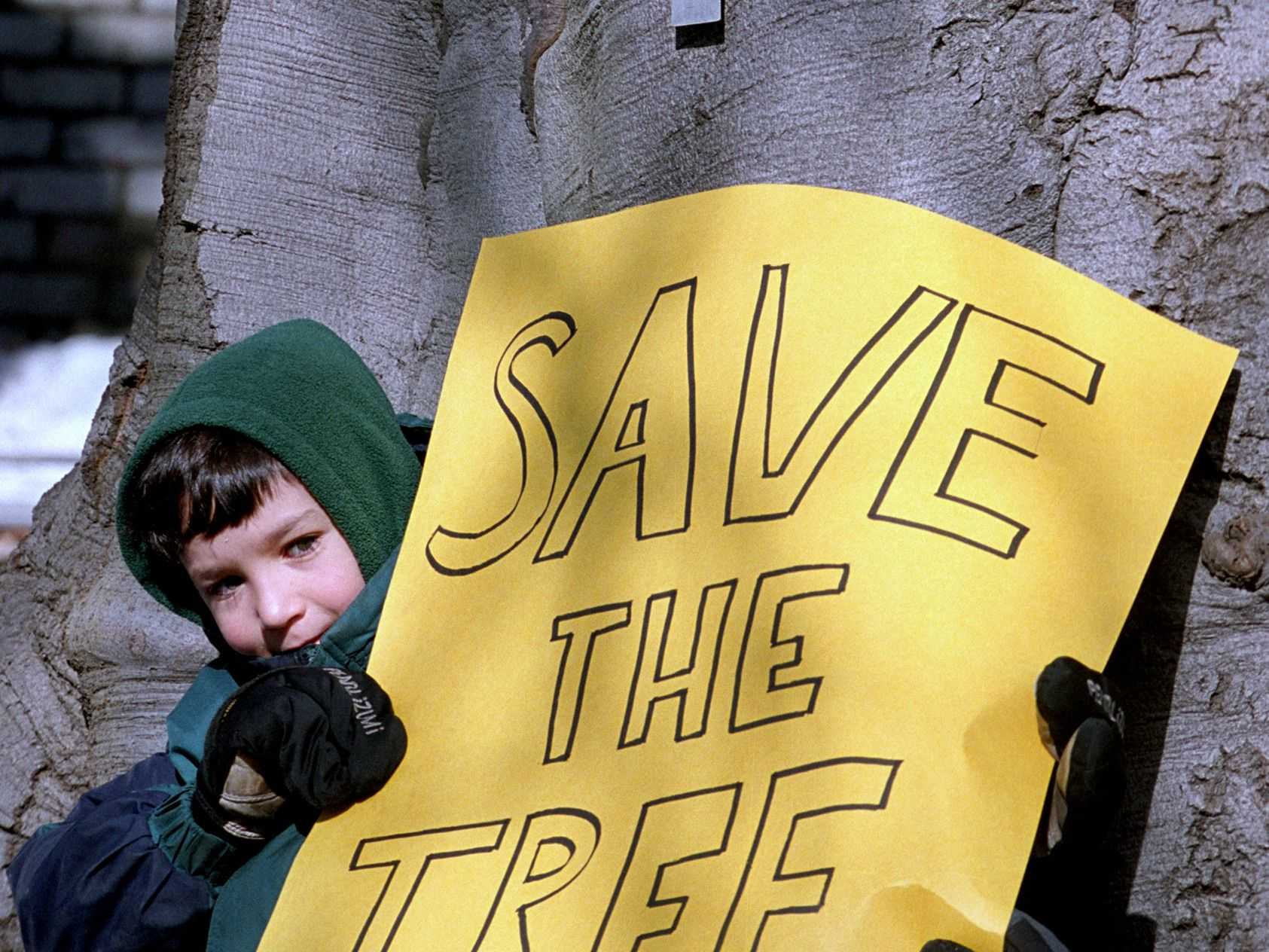

Clockwise from top: The site where the “The Million Dollar Tree” stood outside St. Aidan's Church in Brookline, where a housing project was scaled back, in part, to save a tree. The tree died and had to be removed last year. A child joined a protest to save the 150-year-old copper beech tree from destruction in 2003. Members of the steering committee of the campaign to preserve St. Aidan's stood outside the church in 2001. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff, Amy Newman for The Boston Globe)

The archdiocese dialed back and agreed to preserve part of the church. Opponents then shifted their mission to protecting a 150-year-old copper beech tree in the path of construction. The tree inspired so much fervor — prompting letters to the editor and poems to the Zoning Board — that the planners decided to preserve it, too, though not without sarcasm. Town leaders took to calling it “The Million Dollar Tree.” One church official told the Globe that although it was a “very nice tree … if it comes down to housing 10 more families in need or keeping the tree, I’m going to vote for the 10 families in need.”

Brookline did not. When the St. Aidan’s development opened after an 11-year saga, it had only 59 units — 42 percent of the original proposal — and only 36 of them were affordable. When the first 20 low-income apartments were advertised, 500 people applied, the Globe reported.

The “Million Dollar Tree” was saved, but only for a time: It succumbed to beech leaf disease and had to be removed last year.

Deborah Brown, president of Brookline’s Community Development Corporation, is no longer surprised by her town’s resistance to change. At a public hearing in October, she challenged residents to consider if racism plays a role in their reluctance to allow more multifamily housing. She also noted that her 2018 proposal to rename a public school, which had been named after a slave owner, faced strong opposition before it ultimately passed.

“If people fight that hard for a name,” said Brown, ”what are they willing to do if they think their real estate values are in jeopardy?”

A fight for the future

Colorful yard signs that dotted Brookline lawns in May illustrated the divisive political fight between two factions in one of the most hotly contested local elections in recent memory.

“Let’s Make a Plan,” said the blue-on-white sign of Brookline by Design, the group that wants to limit development.

“We’re for Housing. Transit. People,” said Brookline for Everyone’s sign, featuring a silhouetted image of a streetscape.

The dueling groups were campaigning to get allies elected to town government to shape Brookline’s response to the state’s new housing law, known as the MBTA Communities Act. That law requires communities to change their zoning to permit more multifamily housing near transit lines, though there are no requirements that they actually be built or limits on what developers can charge.

Yard signs from two competing housing groups dotted neighborhood lawns in Brookline before an emotionally heated local election last May. (Jonathan Wiggs /Globe Staff)

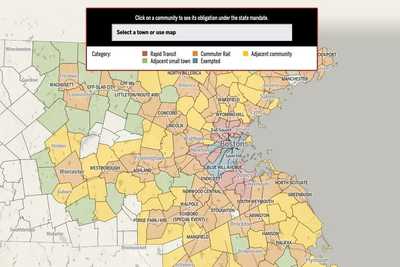

Specifically, Brookline is being asked to rezone 41 acres of land near the Green Line to accommodate a potential 6,990 multifamily units.

At the upcoming Town Meeting, the members will have to settle on the specifics of a plan.

The focus of the fight has long been the bustling commercial districts along Harvard Street.

Town planners had proposed rezoning the thoroughfare from Brookline Village to Coolidge Corner, an area that’s densely developed but seen as underutilized. Originally expected to rise to four stories, the streetscape is now dotted with storefronts of only one or two, due to zoning restrictions. With plenty of room for above-the-shop residential units, Harvard Street could accommodate hundreds more apartments in the area of town most accessible to transit, the town estimates.

That notion appeals to young people like 27-year-old Kevin MacKenzie, a Brookline teacher who doesn’t have a car and who shares a Cleveland Circle apartment with roommates so he can afford to live in town.

“It makes sense to build more housing in areas that already are more dense anyway,” said MacKenzie. “Because one of the issues we often run into in Brookline is, when you try to build housing in areas that are less dense, you get more pushback.”

Map: See how the state’s rezoning mandate affects Brookline and other communities

Click on a community to see its obligation under the state mandate.

But many north Brookline residents resent being asked to fit more housing on their crowded streets. The neighborhood is already a living illustration of the smart growth the state is demanding, they say. Why not explore south Brookline?

“I just want it spread out,” said Fran Perler, a 72-year-old Town Meeting member who lives in north Brookline near Kennedy’s birthplace. “I feel north Harvard Street, this area, has been burdened by a tremendous amount of development.”

Whatever the outcome of the debate, even if the state law does generate more housing across the region, its opponents doubt that it would bring down prices in Brookline.

“We don’t buy it. The demand to live in Brookline is basically infinite,” said Olson Pehlke last spring. “We have good schools and the entire world wishes they could live here.”

In the past month, however, a compromise between the two sides emerged. Select Board member Paul Warren — who had been among the founders of Brookline by Design with Olson Pehlke — brokered a deal between the two groups. Brookline by Design appeared to concede some significant ground in allowing multifamily development along Harvard Street.

Still, significant challenges remain. Though the new state law called for a simple majority to approve rezoning in these matters, the latest Brookline compromise contains special provisions that require a two-thirds majority. If the town fails to produce a rezoning plan by the end of this year, it could lose some state funding and the town could face legal action from the attorney general.

That means New England-style democracy — along with this suburb’s capacity for change — will be tested when Town Meeting convenes beginning on Nov. 14.

Warren is hopeful that the members of Town Meeting will open the door to change in Brookline.

“But there’s 255 Town Meeting members,” he said. “And they’ll decide.”

Stephanie Ebbert can be reached at [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Beyond the gilded gate

People in and around Boston are being challenged, in ways never before, to address the region's unprecedented housing crisis. The Globe Spotlight Team probed this question and found yet another crisis: One of consensus and will.

Preview: Data

Graphics: Why it’s so hard to afford housing in Boston

Part 1: Milton

In towns like Milton, home prices are a threat to prosperity. But they don’t have to be

Map

How will the state’s historic rezoning mandate affect your community?

Part 2: Generations

One house, one family, and the fading dream of homeownership

Part 3: Luxury towers

Reckoning with Boston’s towers of wealth

Part 4: Brookline

An identity crisis comes to Brookline

Part 5: Single-family zoning

Reimagining an American ideal

Part 6: The renters

A Boston building, scattered souls, and rent control revisited

Part 7: Construction costs

The $600,000 problem. Why does it cost so much to build housing in Boston, and what can we do about it?

Calculator: Construction costs

Calculator: Penciling out a project

Credits

- Reporters: Mark Arsenault, Andrew Brinker, Catherine Carlock, Stephanie Ebbert, Diti Kohli and Rebecca Ostriker

- Editors: Patricia Wen, Tim Logan, Mark Morrow

- Photographers: Lane Turner, Jessica Rinaldi, Erin Clark, Craig F. Walker, Pat Greenhouse, David L. Ryan, Jonathan Wiggs

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and Bill Greene

- Video producers: Olivia Yarvis, Randy Vazquez, and Dominic Smith

- Video director: Anush Elbakyan

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development, graphics, and data analysis: Daigo Fujiwara

- Development: John Hancock, Andrew Nguyen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanac and Jenna Reyes

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC