Boston

John Thibault fell in love with the Four Seasons One Dalton, a soaring tower in Boston’s Back Bay, the first day he saw it.

“The views are amazing,” Thibault said of the city’s tallest residential building, hailed as a pinnacle of Boston’s luxury building boom when it opened in 2019. “The amenities, the restaurants, the service — it’s to die for.”

The retired high-tech executive and his wife, who live in Chelmsford, paid $5.25 million for a 2,200-square-foot flat with floor-to-ceiling windows on One Dalton’s 32nd floor. Like many who own condos in this 61-story tower, they stay there only some of the time.

It’s no ordinary pied-a-terre. Perched above a five-star hotel, One Dalton’s residences promise a “curated lifestyle” with Four Seasons attractions — spa, swimming pool, room service — and sell for up to $34 million. Buyers have included billionaire car dealer Herb Chambers, a former Saudi spymaster, and enough corporate CEOs, venture capitalists, and other one-percenters to fill several boardrooms.

His neighbors in the building have been very friendly, Thibault said. As for the high-performing staff, “We get to know people by name.”

But there are dozens of other names Thibault doesn’t know — people who are also closely linked to One Dalton. Under other circumstances, they might have been his neighbors, too.

Their lives are the other side of Boston’s luxury housing story, the one that sits in the shadow of the tower.

One and a half miles away, Alonzo White, a cook with a peddler’s license, lives in a spartan beige brick building in Roxbury’s Nubian Square – the former Tropical Foods grocery store, now rehabbed for housing. When he pulls back the blinds in his living-room window, he can easily see the gray-glass pillar of One Dalton soaring into the sky.

White, his mother, and a younger brother pay about $1,600 a month to rent a three-bedroom apartment here. It’s one of 28 affordable units whose creation was funded by One Dalton’s developer, as part of a set-aside agreement mandated by the city.

In such agreements, income-restricted units are sometimes created in the developer’s original building. One Dalton’s developer funded their construction off-site.

“We were happy to get the apartment,” said White, whose mother, a health care analyst, won an affordable-housing lottery to secure the space. They’re glad to be there, they said, despite the cracks in one wall and the denizens of nearby Methadone Mile they’ve seen hanging out near the front entrance.

These two families living far apart on the housing spectrum embody one of the biggest challenges facing city and state leaders: Just who is the city of Boston being built for?

As an unprecedented housing crisis grips the region, finding an affordable home has become tougher for Bostonians than ever. Costs just keep rising: The median sales price for single-family homes in the city hit a record $908,000 in June, while the median condo price set an all-time high of $775,500 in May, according to the Greater Boston Association of Realtors.

To afford that, a household would need an annual income of almost $300,000 for the single-family home, or more than $255,000 for the condo, to cover mortgage and other costs, said Daniel McCue, senior research associate at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. That’s around three times what the median Boston household actually makes, about $86,000, Census figures show.

Yet alongside this grim picture of housing out of reach, Boston is experiencing an unprecedented luxury high-rise building boom. Gleaming towers for the ultra-rich have sprouted across the skyline, from the Fenway to the Seaport. Thousands of condos have hit the market in high-end developments, with many selling for $2 million, $5 million, $10 million, and more.

For most people, such price tags are mind-bendingly out of reach. In fact, as the housing gap widens, the sheer scale of Boston’s luxury boom has become increasingly conspicuous. What may have been a source of pride and delight for city leaders in the past — evidence of Boston’s burgeoning economy and “world class” status — now prompts a more uncomfortable set of calculations.

On the one hand, leaders know these glittering towers generate needed jobs, tax revenue, and — through government mandates — some affordable housing. On the other, they know that these opulent units serve only a tiny sliver of the population, and that many super-wealthy buyers don’t really call them home. Rather, such condos are often second or third residences, or simply investments — many purchased by anonymous shell companies, sometimes by buyers abroad.

A closer look at the luxury building boom also reveals a blunt reality: Developers disproportionately chase profits at the highest end of the Boston market. A Boston Globe analysis found that by one measure, developers built about five times more luxury condos per household for the ultra-affluent in recent years than affordable units for those of lower income.

To put it more bluntly, Boston is massively better at housing the rich than those who really need a home.

With so many residents struggling to pay for housing, Boston now faces a moment of reckoning, one that raises urgent questions about the city’s social and economic priorities — and its future.

How much should deep-pocketed developers and the super-rich, at the highest tier of the real-estate market, now be asked to contribute to help Boston residents at lower tiers? And how forcefully should leaders wield the levers of power to compel them to do more?

In her first two years in office, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu has pushed forward a host of policies to support affordable housing, including some that would directly affect luxury real estate: a boost in the affordable set-asides required of residential developers, and a new fee on multimillion-dollar property sales. Her approach aims to be at once progressive and pragmatic, a calibrated balance of equity and opportunity.

Some of her initiatives have already provoked fierce opposition from developers and real-estate groups.

Wu’s plans will harm investment and “dampen already depressed housing production in the City of Boston,” said Tamara Small, chief executive of NAIOP Massachusetts, a real estate trade group, via email.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu has made housing a priority of her administration. Left: Wu speaks next to new homeowner Gisselle Jimenez and her son at a ceremonial home closing in June. Jimenez received help from programs that provide assistance for first-time home buyers. Right: Wu attends a ribbon-cutting at Raffles Boston, a new luxury hotel and condo tower, in September. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff, Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

At the same time, many housing advocates think Wu’s plans don’t go far enough. “We had hoped for more,” said Kathy Brown, executive director of the Boston Tenant Coalition, of the affordable set-asides. “People are being pushed out of the city.”

Ultimately government leaders’ actions — or inaction — could shape Boston’s identity for decades, experts say.

“The next generation is in trouble, unless they have wealthy parents who can help,” said economist Barry Bluestone, professor emeritus at Northeastern University.

“We have some housing for the very poor,” built with the help of state and federal subsidies, Bluestone said. “And there’s more than enough for the very wealthy. But everybody in between — the working and middle class — is just being priced out of the city at a faster and faster pace. And those are the people who, let’s be honest, make the city.”

Advertisement

In a luxury building boom, One Dalton stands out

In the summer of 2000, placards went up in the marble lobby of the just-opened Trinity Place condo building in Copley Square, making an astonishing claim about what life there would bring: “Total Fulfillment of Needs.”

The signs touted a new full-service, ultra-indulgent lifestyle for Boston’s new-century multimillionaires. The tower offered not just meal deliveries and valet parking, the Globe reported, but staff who could walk your dog, arrange for your car to be serviced, and even help you plan a party.

Since then, luxury developments have marched across the cityscape at an intensifying pace — monumental symbols of Boston’s growing wealth gap.

Downtown there’s Millennium Tower, where a wealthy buyer spent $35 million for a 13,000-square-foot penthouse in 2016. In the Back Bay, a $25 million listing at the Mandarin Oriental Boston showcases a late art collector’s lavish collection. In the Seaport, Boston’s all new, straight-from-the-drafting board neighborhood, one shiny condo building has followed another, culminating in the St. Regis Residences, a harborside high-rise designed to evoke a ship’s billowing sails.

Since 2000, more than 50 sizable developments featuring multimillion-dollar condos — both new construction and renovations — have opened in Boston, according to a Globe analysis of city and state records. In a flurry of activity in the seven years from 2015 to 2021 alone, that included more than 1,000 new condos now worth $2 million and up.

Who can afford such pricey real estate? Less than 2 percent of the Boston population.

To buy a $2 million home generally takes an annual household income of almost $660,000, based on calculations by Harvard’s McCue. Only 1.7 percent of Boston households clear that high bar, according to Census data examined by Evan Horowitz, executive director of the Center for State Policy Analysis at Tufts University.

Yet in the seven-year span, luxury developers built about one condo worth $2 million or more for every four such super-rich households.

Compare that to affordable housing: In the same timeframe, developers created just one affordable unit through various city programs for every 21 middle- or low-income households.

To be sure, there were, in raw numbers, more affordable units built: about 4,700, the city says. But such units are designed to serve a vastly greater share of the population. They are typically restricted to households making 30 to 100 percent of the area median income. That is, the poor and the middle class — more than 37 percent of Boston residents.

Meanwhile, the parade goes on: This year brought Raffles Boston, a luxe hotel and condo building with penthouses topping $10 million, and Winthrop Center, with all manner of amenities, including a wellness spa for “Very Important Pets.” Under construction is the South Station Tower, with Ritz-Carlton-branded condos and a pool deck hundreds of feet in the air.

Clockwise from top: The South Station Tower, a mixed-use development now under construction, will feature Ritz-Carlton-branded condos and a pool deck hundreds of feet in the air. Luxury towers that opened this year include Raffles Boston, where Kristian Vasilev, general manager of the Amar restaurant, sets the tables, and Winthrop Center, an office and residential building with plentiful amenities. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff, Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

Still, Boston’s tallest residential tower — and perhaps the most exclusive — remains the Four Seasons One Dalton.

Every effort is made to cater to owners’ needs. An army of concierges, bellmen, food servers, housekeepers, spa attendants, and managers of all stripes labor to create environments of faultless, full-service pleasure.

Staff aim to keep track not just of residents’ favorite drinks and the names of their dogs, but of personal details like birthdays and anniversaries, former staff told the Globe. “We know everything about them,’ said Janet Shaw, a former One Dalton assistant director of finance. “What they like, who’s visiting, what this person is to them, if they want to avoid this person they don’t like.”

One resident with special cause to be pleased is Richard Friedman, One Dalton’s developer. The CEO of Carpenter & Company, who previously developed the Charles Hotel in Cambridge and Liberty Hotel in Boston, Friedman has moved into a condo in the tower.

“I am very proud of One Dalton and my family and I are delighted to live there,” said Friedman in a statement emailed to the Globe. He declined interview requests.

Other One Dalton residents who spoke with the Globe are thrilled with the experience.

“The view is incredible,” said Chambers, who previously lived in Boston’s other Four Seasons, on Boylston Street. “The people who work there are so special.”

Barbara Krakow, a longtime Boston art dealer with a condo on the 48th floor, said she loves the building’s “cultural and lifestyle coordinator,” who curates special events for residents.

“The service is extraordinary,” Krakow said. “There are some people who always bitch. I sometimes feel like saying, ‘Why don’t you write your pen-pal in Haiti, and tell them how hot it is here?”

Advertisement

In the shadows of the towers

Boston’s luxury high-rises have long had boosters among city leaders. The late mayor Thomas Menino was especially proud of his development legacy, and his successor Marty Walsh, a former building-trades union leader, touted the benefits of such buildings for job creation and affordable housing.

“Oftentimes people will talk about luxury buildings, saying that, you know, we’re not building for the poor,” said Walsh at One Dalton’s topping-off ceremony in 2018. “But what this building actually does, it’s creating opportunities and revenue for middle-class and low-income housing in the city of Boston.”

Boston’s residential building boom has indeed generated many benefits: thousands of construction jobs, many millions of dollars in annual property taxes, and nearly 8,000 new affordable housing units since the year 2000 through the developer set-asides and cash payments mandated by the city’s “inclusionary development policy.”

One Dalton, for example, produced more than $11 million in residential property taxes in fiscal year 2023, according to Justine Griffin, a spokesperson for One Dalton’s developer. The project created an estimated 750-900 construction jobs and 250 permanent jobs, according to documents filed with the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

But is that enough? Not nearly, critics say.

One Dalton and other “swanktuaries” are symbols of a “grotesque wealth inequality,” said Chuck Collins, a local author and program director at the progressive Institute for Policy Studies, whose research team published an in-depth report on Boston’s luxury building boom in 2018. Analyzing property records for a dozen buildings, they concluded that many buyers were part-time residents or investors, and that many multimillion-dollar condos were likely to be vacant much of the time.

Lots of these condos aren’t homes, Collins told the Globe. “These are safety-deposit boxes in the sky.”

Development for the super-rich has also diverted construction resources and bid up the cost of land, critics charge. Construction workers have indeed been in short supply during what officials have described as the biggest building boom in city history – and construction labor costs have risen. One 2018 study found that Massachusetts had the worst construction worker shortage in the country.

When labor costs go up, so does a building’s price. “The cost continues to climb, and the rent has to climb,” said John Tocci, CEO of a local construction management firm.

Yet all this construction has generated far too little housing that most Bostonians can afford. Some 42 percent of Boston households are already housing “cost burdened,” according to official city figures, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. People in financial straits must sometimes choose between needed health care or paying for rent, and many middle-income and working-class residents have left the city for less expensive areas.

In our current emergency, local leaders say we can — we must — do more.

“We are in a very dire moment,” Mayor Wu told the Globe. “We need to create more housing. And we need more affordability. And we need more housing that is appropriate for families.”

She also shot down the common contention that “‘no matter what you create, even if you only create luxury housing, it will somehow trickle down and have a positive impact.’ That is not what I’m saying.”

The needs are particularly great for “our working-class residents, our Black and brown residents,” said Boston City Councilor Ruthzee Louijeune. “The housing boom has generated record profits for companies. How do we share that, especially with folks who too often get the short end of the stick?”

“The housing boom has generated record profits for companies,” said Boston City Councilor Ruthzee Louijeune (left). “How do we share that, especially with folks who too often get the short end of the stick?” Right: At a rally outside the State House in March by the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization, attendees called for housing initiatives including legislation that would enable municipalities to adopt real-estate transfer fees. (Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff, Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Advertisement

Empty shells, and a vacancy tax

One summer evening, picnickers lounged on the lawn of the Christian Science Plaza, as the sun slowly set.

Above them, the Four Seasons One Dalton rose into the sky, and hotel lights began to wink on. But many windows of the residences on the upper floors were pitch black — and they stayed dark all night.

The sight raised an obvious question: Are many condos in such ultra-luxe towers empty much of the time?

It is often hard to tell who owns high-end US real estate, as affluent people frequently buy property through shell companies that protect their transactions’ confidentiality. It’s even harder to know how many buyers actually reside in such residences.

At One Dalton, about 15 percent of the building’s 171 units remain unsold, four years after the building opened, according to city and state records as of Sept. 25. Griffin, the spokesperson for One Dalton’s developer, said that although numerous units are unsold, some are not being marketed at this time.

“These are safety-deposit boxes in the sky.”—Chuck Collins, author and program director at the Institute for Policy Studies, whose research team published a report on Boston’s luxury building boom

Meanwhile almost two-thirds of One Dalton buyers are limited liability companies, trusts, or other entities that can enable owners to obscure their identities.

There is no definitive way to tell how many residents sleep there, or for how many days a year. But there is this suggestive indicator: Only 16 percent of One Dalton’s units have owners who filed for a residential tax exemption, affirming that it was their primary home, city records show.

Because so many condos appear unoccupied, local real-estate broker and analyst Andrew Haigney has even given One Dalton a playful nickname: the “Prince of Darkness.”

“The people who can afford it have a lifestyle where they’re not in Boston all the time,” Haigney said of One Dalton and other luxury buildings. “I’m not sure long-term if that’s great for the city.”

Indeed, the Back Bay tower is not an anomaly. The Globe examined records for 10 of the city’s most expensive buildings, containing more than 1,400 condos. The average assessed value of these units tops $3 million — about 36 times the city’s median household income.

Only around a third of these units have owners who took a residential tax exemption, according to a Globe analysis of Boston Assessing Department records. Almost half the market-rate units in these buildings are owned by LLC’s, trusts, or other entities.

Many buyers in these buildings are no doubt wealthy executives and empty-nesters from around the region. But quite a few are also foreign buyers. Years ago, Boston joined the likes of New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Miami as a mecca for global investors in luxury real estate.

One evening at One Dalton

“Very wealthy people have diversified their portfolios, so they’re not just in stocks and bonds. They have bought real estate that they assume is going to appreciate at least as fast if not faster than the stock market. That includes foreign investors,” said Bluestone, the economist.

When Millennium Tower opened in 2016, buyers came from multiple countries, snapping up condos there in bulk, the Globe found, including a Chinese investment group that bought 22 units for a total of $21.5 million cash — or 5 percent of the whole building.

Since 2015, international buyers have spent about $695 billion on US residential property, according to the National Association of Realtors. In the 12 months ending March 2019 — the year One Dalton opened — Chinese buyers alone spent $670 million on Massachusetts residential real estate, the association reported.

Friedman, the developer, initially predicted foreign buyers would purchase 30 percent of One Dalton’s condos; he has also said that most owners are local.

Left: Richard Friedman, developer of the Four Seasons One Dalton, observes its construction in March 2018. Right: Friedman is joined by Boston Mayor Marty Walsh at the topping-off ceremony for the tower in August 2018. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

“Many of them moved into the city from the suburbs,” he stated via email. “Our buyers are major contributors to the economy, many of them own businesses and hire large numbers of people. They support local restaurants and shops and are major donors to Boston charities.”

When asked recently what percentage of buyers were international, Friedman declined to answer.

Whether properties are bought by investors here or abroad, concerns have grown about real-estate speculation pushing prices up and owners leaving their properties unused in a super-tight market.

Other cities have started to use tax incentives to address the problem. Voters in San Francisco and Berkeley, Calif., last year approved new taxes on vacant residential property to tame investment speculation and prod corporate landlords and other owners to rent unused units.

One vacancy tax cited as a model is Vancouver’s, which generated more than $115 million for affordable housing in 2017-2021, according to official figures. The number of vacant properties also dropped by 36 percent from 2017 to 2021.

Real-estate groups generally oppose vacancy taxes — and some even argue that empty investment properties can be a plus for society: “If they’re vacant,” said Theresa Hatton, CEO of the Massachusetts Association of Realtors, “they’re not using the schools, contributing to the traffic problem, putting extra burdens on the resources of the city. Why would you want to disincentivize that?”

When Wu ran for mayor in 2021, her campaign materials said Boston should “[p]ursue a vacancy tax on those who buy housing without ever intending to live there.”

But as interest rates have soared and dampened construction, Wu’s administration has recalibrated, focusing for now on more urgent priorities, such as housing production and affordability. “We are in a very different economic moment now,” Wu said.

Advertisement

Tapping dollars from high-end sales

Another city plan would tap a fraction of the dollars flowing from high-end real-estate sales to support affordable housing. But that can’t happen without State House approval.

Wu signed a home-rule petition last year, seeking to introduce a “transfer fee” of up to 2 percent on real-estate sales of $2 million or more, paid by the seller. The plan would exempt the value of the first $2 million of any home.

If this fee had been in force from 2019 to 2022, it would have produced almost $384 million for affordable housing, according to city officials’ estimates.

Similar requests have gone nowhere on Beacon Hill before, including one from Walsh in 2019.

Real-estate groups strongly oppose such measures. “Transfer taxes will only increase the cost of housing … while dissuading needed new investment,” said Small, the trade group leader.

But momentum has built across the state, with about a dozen cities and towns requesting their own transfer fees and state lawmakers introducing bills that would let any municipality do so.

Boston also recently gained a powerful ally: Governor Maura Healey.

The Healey administration’s Affordable Homes Act, unveiled in October, would let municipalities across the state adopt their own transfer fee of 0.5 to 2 percent on real-estate sales above $1 million or the county’s median home price, whichever is higher, to support affordable housing. The fee would only apply to the part of the sale that exceeds those levels.

A transfer fee would make a huge difference for families and seniors in need of homes, said Sheila Dillon, Boston’s chief of housing. The fee, she said, would double Boston’s housing budget to help them.

“It’s a fabulous idea, and one that the state should pass tomorrow.”

Advertisement

The lucky few

Wu’s plan to increase what developers set aside for affordable housing would expand a benefit already being felt by Bostonians — though far too few.

Denise Delgado is one of those Bostonians. A writer and artist with two masters degrees, Delgado serves as executive director of the nonprofit Egleston Square Main Street, which works to revitalize that Roxbury/Jamaica Plain neighborhood.

Four years ago, as a single mom with a salary around $50,000, Delgado was also struggling to pay market-rate rent.

She started applying to affordable-housing lotteries and finally got good news: She won a lottery to buy a new condo in Nubian Square. Then came what she describes as a “white-knuckle” six-month process to qualify and purchase the unit she now calls home — a two-bedroom condo decorated with tropical wallpaper, tucked in a neat gray mixed-income building across from a police station and a small park.

Built by the nonprofit Madison Park Development Corp., it is one of seven affordable condos funded by the One Dalton deal, in addition to 21 affordable apartments in Madison Park’s rehabbed Tropical Foods store.

Because Delgado’s income was less than 80 percent of the area median income, she paid just $221,900. (If she sells the condo, deed restrictions require it to be sold at a below-market price to an income-eligible buyer.)

“It feels amazing,” Delgado told the Globe. “I feel very, very fortunate.”

There are two key things people don’t know about the program, Delgado said. “First, they think affordable housing is just for low-income people, and they think it’s something you’re just given. It’s not. It’s so much harder and more labor-intensive than somebody who is able to afford something market-rate has to go through.”

Boston’s inclusionary development policy currently requires developers of market-rate housing of 10 units or more that seek zoning relief to give back to the city: They can typically make 13 percent of their units affordable, create such units elsewhere, or make a “cash-out” payment to support affordable housing.

The resulting affordable properties, often made available through lotteries, are in tremendous demand.

“For the families that win the lottery it can be life-changing,” said Intiya Ambrogi-Isaza, director of real estate at Madison Park Development.

Boston’s inclusionary development policy has, since its inception in the year 2000, produced almost 4,000 affordable units, while developers’ cash payments under the program have funded the creation of almost 4,000 more, according to a spokesperson for the Boston Planning & Development Agency. That adds up to nearly 8,000 new affordable units in 23 years.

Around 350 a year. Nowhere near enough, housing advocates say.

The two housing lotteries connected to the One Dalton deal underscore the scale of the need. Thousands of people applied for those 28 units, Ambrogi-Isaza said. Delgado was one of the lucky few.

Looking ahead, there are more than 700 affordable units under construction through the inclusionary development policy, plus more than 3,300 that have been approved by the Boston Planning & Development Agency, the agency spokesperson said.

“For the families that win the lottery it can be life-changing.”—Intiya Ambrogi-Isaza, director of real estate at the nonprofit Madison Park Development Corporation, on affordable housing opportunities

But Mayor Wu is seeking to pick up the pace.

Wu’s plan would require most new buildings to have 17 percent affordable housing, with another 3 percent offered at market rates for Section 8 voucher holders. It would also reduce the size of buildings required to comply from 10 units to seven.

To take effect, the plan now only needs approval from Boston’s Zoning Commission. It was approved by the Boston City Council, even after several city councilors joined neighborhood and housing advocacy groups in saying it didn’t go far enough.

Developers had also voiced opposition, and the mayor had faced criticism for keeping them at arms’ length. But there have been signs of warming in her relationship with the business community. In September, Wu said her administration is “strongly considering” tax incentives to accelerate housing production — an idea the business community has embraced — and she joined developers at a festive ribbon-cutting for Raffles Boston, the new luxury hotel and residential tower.

“We have been working with them even more closely than before,” said Arthur Jemison, Boston’s chief of planning and director of the Boston Planning & Development Agency, referring to developers.

A luxury glut, and a view ahead

After years of development, the top of Boston’s real-estate market is softening — at least for now. Luxury sales have slowed nationwide, in part because of higher mortgage interest rates.

With hundreds of expensive units hitting the Boston market and more in the pipeline, developers are sitting on scores of unsold condos in high-end developments across the city, worth more than a billion dollars, according to a Globe analysis of records. There is a housing crisis on the ground, but a surplus in the sky.

Still, there are plenty of profits to be had in that rarified sector. And among One Dalton’s affluent residents, some endorse — to varying degrees — proposals to help those in need of affordable options.

Thibault, the retired high-tech executive, said increasing developers’ affordable set-asides is “a great idea,” as long as affordable units are not inside luxury buildings.

Krakow, the art dealer, solidly backed Wu’s plans. It’s in everyone’s interest, she said, to have housing workers can afford, so they aren’t forced to leave the city.

“There’s a cliche — ‘not in my neighborhood’ — that becomes a real struggle,” Krakow said. “I say, ‘The day you don’t have a gardener or cleaning woman show up, maybe you’ll rethink the issue.’”

Rebecca Ostriker can be reached at [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Beyond the gilded gate

People in and around Boston are being challenged, in ways never before, to address the region's unprecedented housing crisis. The Globe Spotlight Team probed this question and found yet another crisis: One of consensus and will.

Preview: Data

Graphics: Why it’s so hard to afford housing in Boston

Part 1: Milton

In towns like Milton, home prices are a threat to prosperity. But they don’t have to be

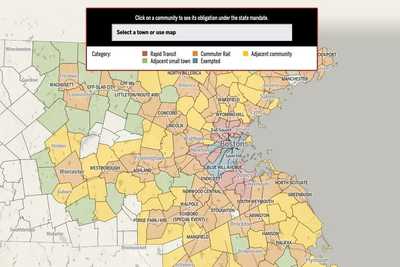

Map

How will the state’s historic rezoning mandate affect your community?

Part 2: Generations

One house, one family, and the fading dream of homeownership

Part 3: Luxury towers

Reckoning with Boston’s towers of wealth

Part 4: Brookline

An identity crisis comes to Brookline

Part 5: Single-family zoning

Reimagining an American ideal

Part 6: The renters

A Boston building, scattered souls, and rent control revisited

Part 7: Construction costs

The $600,000 problem. Why does it cost so much to build housing in Boston, and what can we do about it?

Calculator: Construction costs

Calculator: Penciling out a project

Credits

- Reporters: Mark Arsenault, Andrew Brinker, Catherine Carlock, Stephanie Ebbert, Diti Kohli and Rebecca Ostriker

- Editors: Patricia Wen, Tim Logan, Mark Morrow

- Photographers: Lane Turner, Jessica Rinaldi, Erin Clark, Craig F. Walker, Pat Greenhouse, David L. Ryan, Jonathan Wiggs

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and Bill Greene

- Video producers: Olivia Yarvis, Randy Vazquez, and Dominic Smith

- Video director: Anush Elbakyan

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development, graphics, and data analysis: Daigo Fujiwara

- Development: John Hancock, Andrew Nguyen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanac and Jenna Reyes

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC