Boston. Racism. Image. Reality. Seaport

A brand new Boston, even whiter than the old

The series was reported by Andrew Ryan, Nicole Dungca, Akilah Johnson, Liz Kowalczyk, Adrian Walker, Todd Wallack, and editor Patricia Wen. Today's story was written by Ryan.

Imagine a fresh start — a chance for Boston to build a new urban neighborhood of the future, untouched by the bigotry of the past.

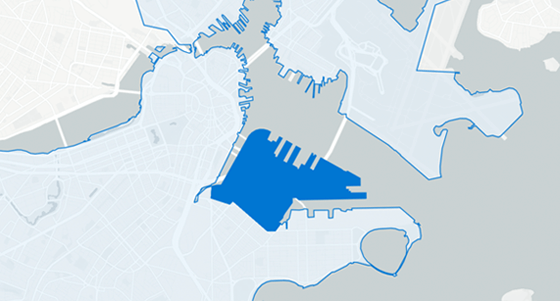

Start with a swath of nearly 1,000 acres, where rotting railroad piers and asphalt parking lots had lain fallow for generations. Invest more than $18 billion in public money to create some of America’s most valuable property. Envision a seaside neighborhood that city planners said would be for all Bostonians.

And what happened? One of the city’s whitest neighborhoods was born.

In Boston’s thriving Seaport, the pre-dawn joggers are almost all white. The morning rush of commuters — lawyers, accountants, scientists, and financiers — includes very few black faces. The same whiteness dominates night life at the Envoy Hotel’s roof-top bar, such restaurants as Strega Waterfront and Babbo Pizzeria e Enoteca, bowling at Kings Dining & Entertainment, and the yoga and exercise classes out on Seaport Common.

How white? This white: Lenders have issued only three residential mortgages to black buyers in the Seaport’s main census tracts, out of 660 in the past decade. The population is 3 percent black and 89 percent white with a median household income of nearly $133,000, the highest of any Boston ZIP code, according to recent US census estimates.

But what happened in the Seaport is not just the failure to add a richly diverse neighborhood to downtown. It is also an example of how the city’s black residents and businesses missed out on the considerable wealth created by the building boom. This is a city in which blacks are almost a quarter of the population, and their tax dollars were part of what helped jump-start the new Seaport.

“It is a brand-new neighborhood and it’s not diverse,” said Darryl Settles, a real estate developer and restaurateur, who is African-American. “I don’t know one person of color that has made any money from the development of the Seaport. Not one.”

The Spotlight Team scrutinized the Seaport in its examination of whether Boston still deserves its reputation as an inhospitable place for blacks. Despite the vision decades ago by the city’s top development official as a place “for all Bostonians” to reconnect with the waterfront, the Seaport has become like an exclusive club created, frequented, and populated almost exclusively by the white and the wealthy.

The Seaport offered the potential to do more than build glass towers with harbor views. After decades of government investment, it offered a chance to build something not just new, but different. It offered a chance to make inclusivity a real priority by pushing for diverse development teams and businesses that reached beyond the clubby world of Boston’s traditional powerbrokers to share prosperity.

Consider the predicament faced by a prominent local black investment manager when Boston hosted the National Association of State Treasurers’ conference in September. He wanted to show off the city’s hot new neighborhood to a diverse contingent of officials from across the country, but he did not want them to be the only people of color in a restaurant or bar.

“I asked around to my younger friends and I couldn’t find any place” in the Seaport, said Ron Homer, a former chief executive officer of the Boston Bank of Commerce, who ultimately took the group to Slade’s Bar & Grill in Roxbury. “That wouldn’t happen in New York or Chicago or [Washington,] D.C. or Atlanta. The Seaport reflects where the wealth and demographics of Boston are.”

Diversity was never a real priority, and now some black leaders say the neighborhood has perpetuated the racial and economic segregation that have always bedeviled Boston. The Seaport’s whiteness is not the result of overt prejudice, they say, but rather a symptom that indicates Boston has not addressed systemic issues involving race. Billions of dollars in public investment offered leverage to push harder for inclusion, but some believe government officials squandered that chance to enrich all Bostonians, including black residents.

“You want people to have opportunities to literally create wealth so they aren’t just working down there, they are buying down there, they own the businesses that are down there, they are part of the DNA of the place,” said M. David Lee, a prominent African-American architect. “They add interest and fresh ideas and music and cuisine. It would be richer because of the racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity.

“It could be,” Lee said, “a whole new way of thinking about Boston.”

A pricey neighborhood

There is more than one explanation for why so few black people are seen on Seaport Boulevard.

The Seaport is a hard-to-reach peninsula far from the region’s black populations. Lousy public transportation there exacerbates the problem in a neighborhood served predominantly by the Silver Line hybrid bus.

Parking in the Seaport can cost $30 for three hours when shoppers can park for free, for example, at another new development, Somerville’s Assembly Row, which is often more diverse than the Seaport.

The dearth of blacks in the Seaport also reflects the jobs that have taken root in the new district. Boston’s traditional industries there, including investment services, law, and accounting, all struggle with diversity. Black workers may be even scarcer in such life science and high-tech firms as Vertex Pharmaceuticals and LogMeIn that give the Seaport cachet as the “Innovation District.”

In those booming industries, diversity is often marked not by blacks, but by international workers. Cambridge’s Kendall Square, the region’s first innovation hub, faces the same challenge. Nationally black employees account for 7 percent of high-tech workers and they are more likely to be technicians at the lower end of the pay scale, according to 2014 data from the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Another explanation for the Seaport’s lack of diversity is economic. Condominium and apartment prices are sky high. Blame expensive land, high labor costs, new construction, often breathtaking city and water views, and the proximity to Logan International Airport, which imposes strict limitsblocking construction of taller buildings in the Seaport that could pack in more units.

Do you think a lack of diversity is an issue in the Seaport?

Read the discussionBoston does push big developers to build affordable housing, but there are nuances. Developers can satisfy the requirements by writing checks to a housing fund or building lower-priced apartments and condominiums in nearby neighborhoods where land costs less. In the past decade, 9 percent of the about 5,800 new units in the Seaport were designated for people with moderate incomes.

A two-bedroom apartment in the Seaport can rent for more than $5,000 a month and cost more than $2 million to buy. That’s far beyond the reach of most people in Greater Boston, especially the region’s black residents. A 2015 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and a Duke University researcher found that home equity and other assets — minus mortgages and other debts — gave white families a median net worth of $247,500. For African-American, non-immigrant households, the figure was $8.

Bostonians of all races have been priced out of the new neighborhood, said Mayor Martin J. Walsh, who added that he was “not defending the Seaport.”

“The Seaport is this glaring area” that lacks diversity found elsewhere in the city, Walsh said. “There are some black people that feel that they just haven’t been part of it.”

Government can exert influence through zoning, tax breaks, and other incentives, though officials say they had limited control over the evolution of the Seaport as market forces took hold. The city’s top development official, Brian P. Golden, said the Seaport had originally been envisioned as a more residential neighborhood, but investors showed strong interest in commercial development.

“Do I wish that was a more diverse neighborhood reflective of the city and society as a whole? Absolutely,” said Golden, director of the Boston Planning and Development Agency. “But we’ve been using our limited tools to nurture economic development over there for the last 20 years to make sure those benefits are felt in lots of direct and indirect ways throughout the city.”

He noted that while the $18 billion in public investment has not created a racially inclusive waterfront, it has brought jobs, tax payments, and other benefits to “a huge swath of Bostonians.”

Even for blacks who have the money, the Seaport seems to have a clear target audience in marketing pitches that feature few black faces. Advertisements for the luxury condominiums and apartments target empty nesters from the suburbs and often feature well-tanned, graying white men standing on a balcony, relaxing on a sailboat, or urging potential residents to come “live with distinction.”

The Seaport’s identity as Boston’s new luxury brand marks an extraordinary turn for an industrial expanse where it seemed for decades that development would never take hold. Court battles scuttled grand proposals, large landowners let seaside plots sit idle as parking lots, and the Great Recession a decade ago stopped construction cold.

“On a superficial level, what are you complaining about? There are nice shiny buildings, jobs are being created, and taxes are being paid,” said Armando Carbonell of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. “But it raises an important question for any city that is in the Boston, San Francisco, New York mode of success right now. That is, how is that success being shared with the entire population of the city?”

A history of public investment and a long wait

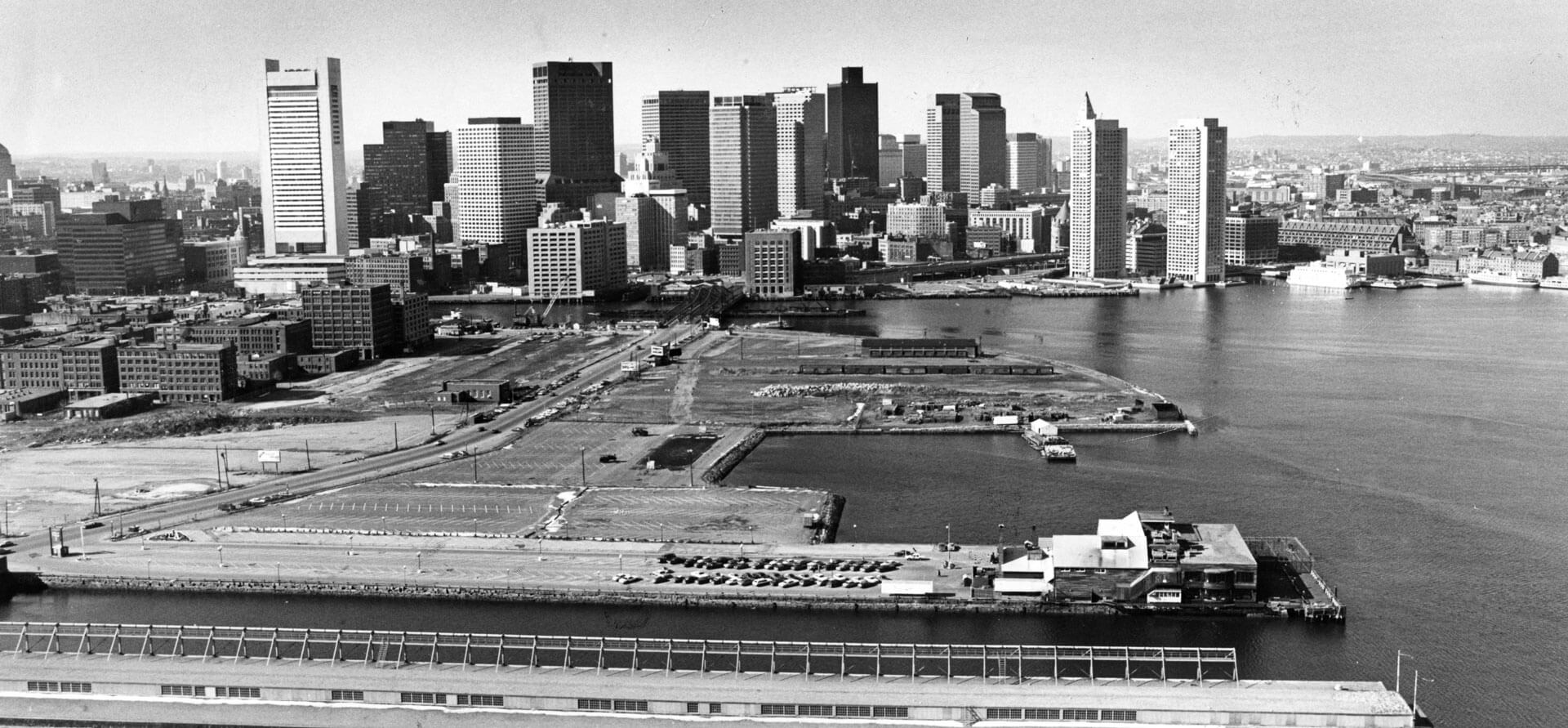

Capitalism may have fueled the current demand for million-dollar condominiums, but the Seaport’s history is more complicated than free market prices. Like so much of Boston, a large share of the land began as clam flats and tidal marshes, and public money was used to transform it.

In 1869, the state Legislature voted to commit $5 million -- in what today would be an estimated $97 million -- in government bonds to subsidize an effort by railroad companies to fill clam flats and build wharves. It eventually became a sprawling railroad yard that moved primarily coal from ocean liners to freight trains bound for Hartford, New Haven, New York, and Philadelphia.

A decline accelerated after World War II, and by the early 1960s, the land became home to Anthony’s Pier 4, a popular waterfront restaurant. It sat in an empty expanse of parking lots and rotting wharfs that became known for failed real estate deals and gangland shootings.

Government interceded again. Taxpayers cleaned the filthy harbor ($4.7 billion), constructed a tunnel through the neighborhood to the airport ($12 billion), built a sprawling convention center ($850 million), extended the Silver Line ($601 million), and built a federal courthouse ($223 million). At least $200 million more in property tax breaks and other financial incentives encouraged construction of office towers and hotels.

Two decades ago city planners envisioned a vibrant Seaport evolving “into a true neighborhood with families,” according to a July 28, 2000, letter from the Boston Redevelopment Authority to the Fan Pier Land Company. They described the new Seaport as “a vibrant urban waterfront.”

“The BRA is committed to making the South Boston Waterfront the city’s next great neighborhood,” read the letter from the redevelopment authority director, Mark Maloney, who described the creation of “residences, offices, hotels, and shops as well as open parks and access to the waterfront for all Bostonians.”

It may now be flourishing, but for a long time the Seaport was no sure bet. Buildings took decades to rise. In 1986 the World Trade Center became a pioneer. More than a decade later came the Seaport Hotel and the new federal courthouse. Other buildings followed slowly, from Manulife tower to the Institute of Contemporary Art.

The surge of construction offered promise, but the financial crash of 2008 halted almost all optimism. Projects were delayed. City Hall then allowed Fan Pier developer Joseph Fallon to postpone a $4.5 million affordable housing payment because Fallon said, according to a December 2010 letter, “the housing market has collapsed, and financing for new construction of condominium units has disappeared.”

But as the economy emerged from the Great Recession, the Seaport regained momentum. Tax breaks continued at developments like a Fan Pier headquarters for Vertex.

Vertex’s 2011 groundbreaking epitomized black Bostonians’ experience in the Seaport. The two-tower project was spurred, in part, by millions in state and city incentives. At the time, it was the largest private sector construction project in America.

Then-Mayor Thomas M. Menino hailed it as a historic step in creating a dynamic waterfront because, “for too long this piece of land was just an aspiration.” A photograph taken that day shows 18 people hoisting a shovelful of dirt for the ceremonial groundbreaking. Only two people in the photograph appear to be black. One is former governor Deval Patrick, who described the project as a symbol of the transformation of Massachusetts’ new economy.

But there were few black people involved in the development of the building or the leadership of the company — a common story across the Seaport. Management at the Fallon Company does not appear to include any blacks or African-Americans, according to a review of trade publications and online employment profiles. The Fallon Company declined to comment and did not disclose demographic data for its employees.

None of the 21 companies on the development team — engineers, curtain wall consultants, architects, elevator specialists — had black ownership or black executives in leadership, according to a November review of company websites.

Vertex did not appear to have any black executives on its 18-member leadership team or serving on its nine-member board, according to a review of the company’s website, trade publications, and online employment profiles. Vertex declined to provide detailed demographic data, but a spokeswoman said last week their web site does not reflect a black executive who was promoted in October.

Seaport developers acknowledge that the new neighborhood would not exist without billions in public investment, but they contend that sky-high costs for land, materials, and construction labor necessitate the neighborhood’s luxury prices. Inadequate public transportation has required underground parking garages, pushing prices even higher.

Projects carry tremendous financial risk, developers said, and investors demand that architecture and engineering firms have proven track records. The building boom, they also said, has created tens of thousands of jobs that have benefited African-Americans and other people of color.

Developer John B. Hynes III put the neighborhood’s diversity on par with other tony neighborhoods like the Back Bay but said it was “not an unfair observation” that the Seaport lacked blacks.

“There’s not intent or any of that,” said Hynes, who initiated the massive Seaport Square project. “Why aren’t there more minorities buying into the area? The short answer is because they’re priced out. Why don’t we get them to different [income] levels? Well that’s a question I don’t have an answer for.”

Creating wealth predominantly for whites

Development nationally is an overwhelmingly white industry, but high-powered black developers do exist in other cities. Some of the best known are New York’s R. Donahue Peebles, Chicago’s Quintin E. Primo III, and Harvard Business School graduate Kenneth Fearn of Los Angeles.

In Boston, the teams assembled by Fallon and the other big builders are overwhelmingly white — engineers, land surveyors, traffic consultants, lawyers, realtors, interior designers, public relations firms, commercial brokers, and permitting specialists. Almost no blacks hold leadership roles in Boston’s construction unions or at the general contractors that have built the Seaport.

Look, for example, at the Watermark Seaport, a $126 million development completed in April 2016 on Seaport Boulevard with 346 luxury rental high-rise apartments and modern lofts. The project owners — Skanska and Twining Properties — have no black people on their management teams, according to the companies.

The corporate leadership of the architecture firm is entirely white men. There are no black faces in leadership pictured on company websites at the project’s five engineering firms.

The Globe could not find a single black senior executive at any of the 14 firms on the project team. That included the landscape architect, acoustic consultant, elevator consultant, and lighting consultant.

John Moriarty & Associates, a construction firm, has built a significant part of the Seaport. The firm’s namesake, John Moriarty, said he cares about diversity and has forged a recent partnership with Greg Janey, the black owner of a smaller construction firm. But Moriarty said he also understands why Seaport investors return to the same firms for project after project.

“If you’re going to spend $500 million, are you going to do it with somebody who has done it before? Or are you going to do it with somebody who is just learning?” Moriarty asked. “Of course you’re going to do it with somebody who has a track record and your investors can feel comfortable with.”

Boston City Hall often tussles with developers over design, height, open space, and parking. But the Boston Planning and Development Agency — which has no black staffers in leadership — does not make a point of pushing for inclusive development teams. Often the same firms get tapped for project after project.

“None of us have really gotten any work down there,” said Lee, the architect, although his firm did help design the Manulife building nearly 20 years ago. “There’s no pressure for it. No one is saying, ‘Where’s the diversity on your team?’ Without that kind of pressure, it doesn’t happen.”

The city has achieved some success in diversifying the building trades, although the ironworkers, electricians, and other construction workers still skew disproportionately white. For more than three decades, a Boston law has required that at least 25 percent of construction hours on major developments go to people of color — a standard Mayor Walsh increased in January to 40 percent. Contractors can face financial penalties for failing to comply, although the city has not levied a fine since 2011.

A mayoral spokeswoman said the new law makes it easier to institute penalties, but the city’s ultimate goal is to work with developers and contractors to create “a more diverse and equitable workforce.”

In the Seaport, construction workers have logged nearly 9 million work hours since 2006, earning hundreds of millions of dollars. On average, contractors met the old minimum of 25 percent for construction workers of color who were black, Latino, or Asian, according to a Globe analysis of data collected by the city.

But even the 25 percent minimum threshold still left an imbalance in a city where white residents make up less than half the population but perform 75 percent of the construction work. A Globe analysis found that for every hour of employment for a black construction worker, a white construction worker got nearly a full day’s work.

Some signs of potential

Massport and L. Duane Jackson are trying to make a difference in the Seaport.

He is a black real estate investor with advanced architectural and city planning degrees from MIT. Despite his local stature and the fact he’s lived here for nearly a half century, Jackson still does not consider Boston his home. He travels — New York, Miami, Philadelphia — to get his cultural fix because, he said, “there isn’t an affinity for me here in Boston.”

Too often he has felt the sting of prejudice, most painful when the targets were his sons, both of whom were wrongly detained years ago in separate incidents by local police, Jackson said. Both of his boys are grown and have forged successful careers far from Boston.

![Massachusetts Port Authority board member L. Duane Jackson initiated a new policy that made diversity a component of scoring for contract and development bids. “The more we change the public perspective and perception of Boston, particularly as a place to do business...African-Americans and Latinos [will] feel more welcome here,” Jackson said.](/spotlight/boston-racism-image-reality/assets/methode/walker-04738_apps_w_placeholder.jpg)

Jackson serves on the board of the Massachusetts Port Authority, which owns big swaths of land in the Seaport. He initiated a sweeping new policy that won unanimous support: Alongside design and financing, diversity now represents 25 percent of an evaluation score for contract and development bids. Instead of setting a minimum benchmark for construction workers, the agency emphasized firms owned by women and people of color.

“You’re talking about a city that has a history and legacy of racial bias, but I believe that there are a fair amount of good businessmen who want to work collaboratively and collectively to achieve goals larger than just a return on investment,” Jackson said. “The more we change the public perspective and perception of Boston, particularly as a place to do business . . . African-Americans and Latinos [will] feel more welcome here.”

The first project won approval this spring: a $550 million, 1,000-plus room Omni hotel with a development team brimming with black investment teams and firms. The emphasis on diversity pushed executives outside their normal networks and formed new alliances. One partnership has already led to new deals between the Moriarty and Janey construction firms.

“There’s only one bullet in the chamber,” Jackson said. “That is the public sector’s willingness to take this on as a fight for economic parity. That’s the game changer.”

Black Bostonians have found welcoming corners of the Seaport. The Venezuela ceviche bar La Casa de Pedro draws a multicultural crowd and so can the Lawn on D and special events at the Institute of Contemporary Art. A black-owned barbershop recently opened. In a neighborhood still pockmarked by undeveloped parking lots, potential remains to infuse the Seaport with the diversity reflecting a modern Boston.

“It has to be a real priority on the side of owners and decision-makers,” said Daren Bascome, who is black and founder of Boston-based Proverb, a company that helps cities, cultural institutions, and commercial real estate firms create a sense of place. “If you want something that feels hip and urban and cosmopolitan, you really do want a broad cross-section of occupants in those buildings.”

Like all of America’s largest cities, Boston has become less segregated in recent decades. But growing Western metropolises like Phoenix, San Diego, Seattle, and Houston have become even more integrated as the urban area expanded and new neighborhoods formed, according to census data analyzed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Geography makes Boston’s Seaport unique, and national comparisons can be difficult. In Washington, D.C., District Wharf draws a diverse crowd to the banks of the Potomac River. Mission Bay in San Francisco has large shares of apartments for low- and moderate-income residents. In Newark, the Powerhouse Arts District has struggled to retain its identity and remain affordable because of its proximity to Manhattan.

“A lot of cities like Boston that consider themselves global cities are competing for the global 1 percent,” said Penn Loh of Tufts University’s Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning. “Boston could lose its soul as a place for regular, working people of all colors.”

On a summer-like night in late September, the Boston Pops Brass Quintet readied their instruments on a small stage in Seaport Common. The new public space had finally come to life as people gathered on blankets spread over patches of grass. The crowd numbered roughly 175 and only six appeared to be black. An announcer on stage introduced the quintet and said, “Thank you to WS Development for turning this mud flat into a beautiful neighborhood.”

The next night, guests sipped sparkling rosé and India pale ale as music echoed from dueling DJs on two expansive, fourth-floor decks. It was the grand opening for the Seaport’s two new apartment high rises: The Benjamin — as in Boston native Benjamin Franklin — and its hipper next-door neighbor, the VIA.

The side-by-side luxury buildings — which house 832 apartments, including 96 for moderate income renters — offer residents expansive fourth-floor common areas that are like private clubs above the city. Picture a swimming pool, outdoor fire pits, and more.

The white-gloved concierges were predominantly black, but almost all attendees at the opening were white. At the Benjamin’s roof deck party, a reporter counted 12 black people among 185 guests.

One of the black attendees was David Brown, a 24-year-old Army reservist from Hyde Park who has watched the buildings take shape from his job across the street at Capital One.

The modern look of the buildings impressed Brown, who said he liked the posh amenities and sweeping skyline views. One touch particularly struck Brown: three hip-hop dancers performed outside the buildings as guests arrived. It made the event feel more inviting, Brown said, like nobody was stuck up.

“I can see myself living there,” Brown said a few days later. “The prices are kind of crazy, but with a lot of hard work and dedication, someday.”

To contact the Spotlight Team working on this project, write to [email protected] or contact the writer of this story at [email protected].

Do you think a lack of diversity is an issue in the Seaport?