Coventry, R.I. — When 12-year-old Zacheri Lorenzen smelled smoke from his room in the basement of his father’s house, he climbed to the top of the stairs and opened the door. Before him was a terrifying sight: his 2-year-old sister Penny standing alone, staring up at a rising wall of flames.

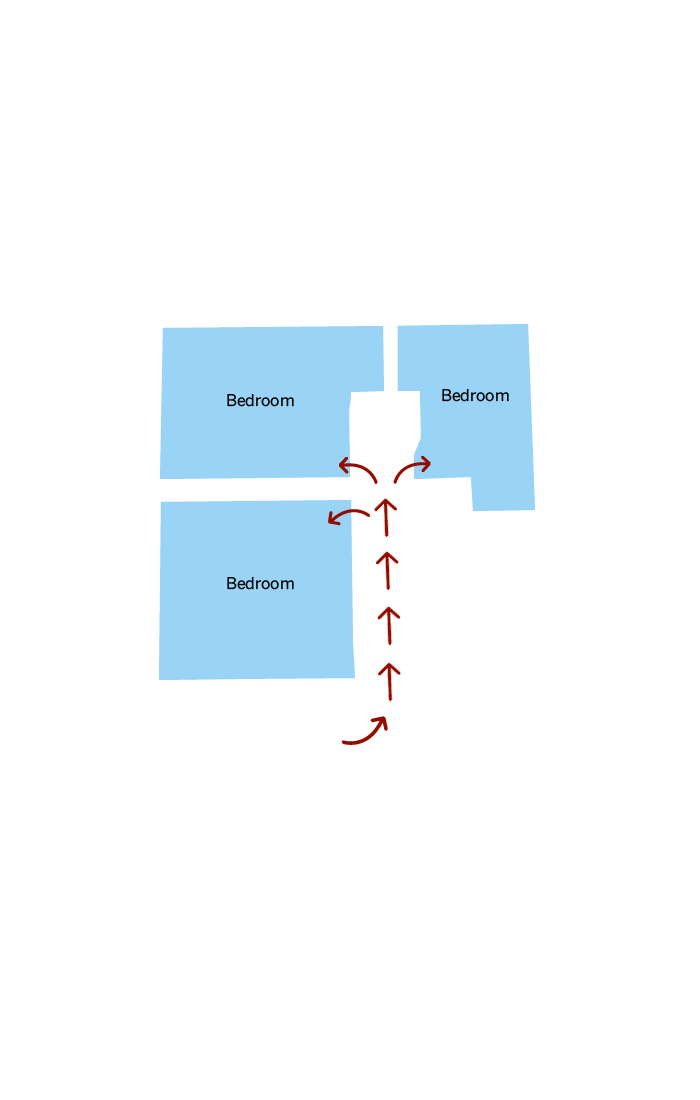

Known for his unflappable demeanor — he was slow to rattle when he pitched for his youth baseball team — Zacheri moved quickly and decisively. He grabbed the toddler in front of him and turned to run back down the stairs, taking care to close the basement door behind him.

Before he did, he shouted a warning to the two family members he did not see anywhere — his father, Ed, and his 4-year-old brother, Michael:

“Get out of the house!”

There was no answer, and no sign of them outside when Zacheri emerged from the basement with his sister in his arms, through the rear bulkhead door into the backyard. As the blaze lit up the chilly January evening, licking through the windows and the roof, the boy dialed 911 on his cellphone and knocked on a neighbor’s door for help.

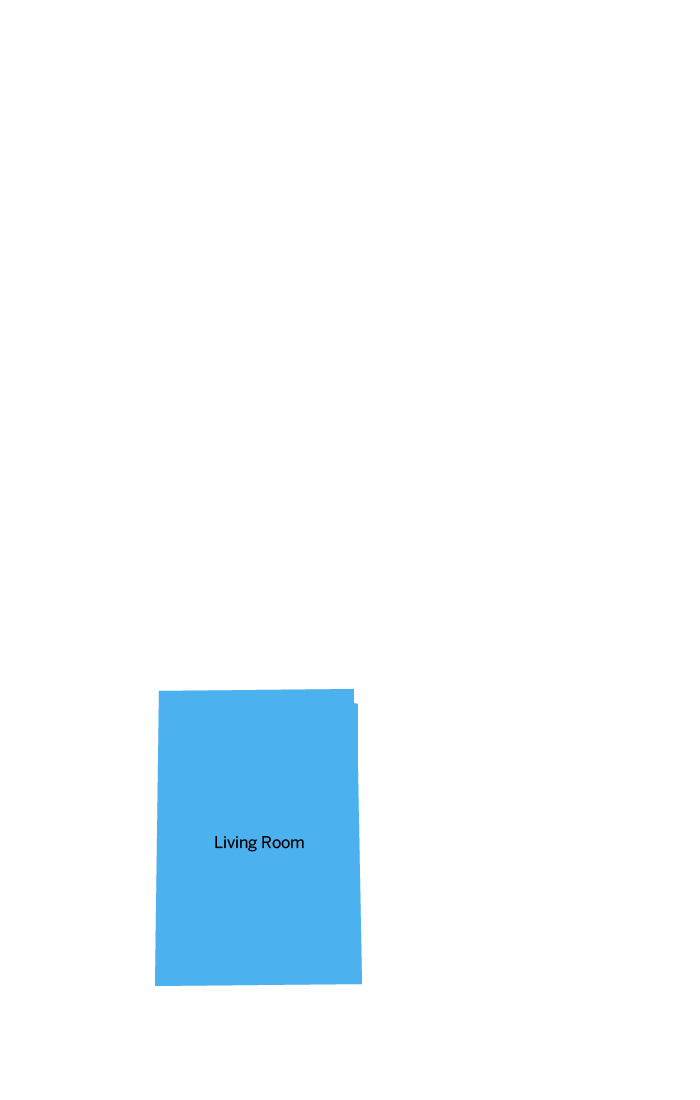

It took firefighters just four minutes to arrive. They rushed into the living room, where, in heavy smoke, they fought to bring the raging fire under control.

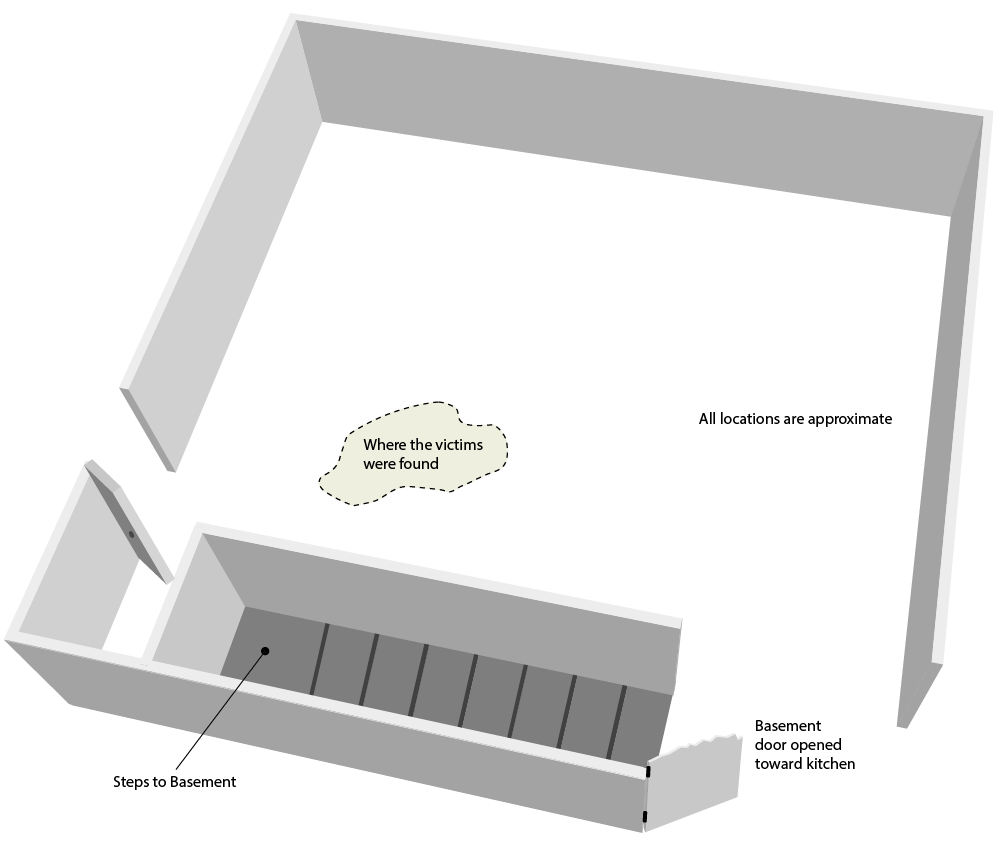

After it was out, as the smoke began to clear, firefighters made the discovery they had dreaded: Edward Lorenzen, 47, a brilliant and beloved policy analyst in Washington, D.C., and 4-year-old Michael were dead, their bodies close together in the living room, a few feet from the front door.

The deaths sent rings of grief rippling outward from the small yellow house south of Providence. Friends and loved ones struggled to understand. It had been dinnertime when the fire erupted, not the middle of the night. And it was a small house, where most every room had easy access to the outside. What could have kept Ed Lorenzen and his son from escaping?

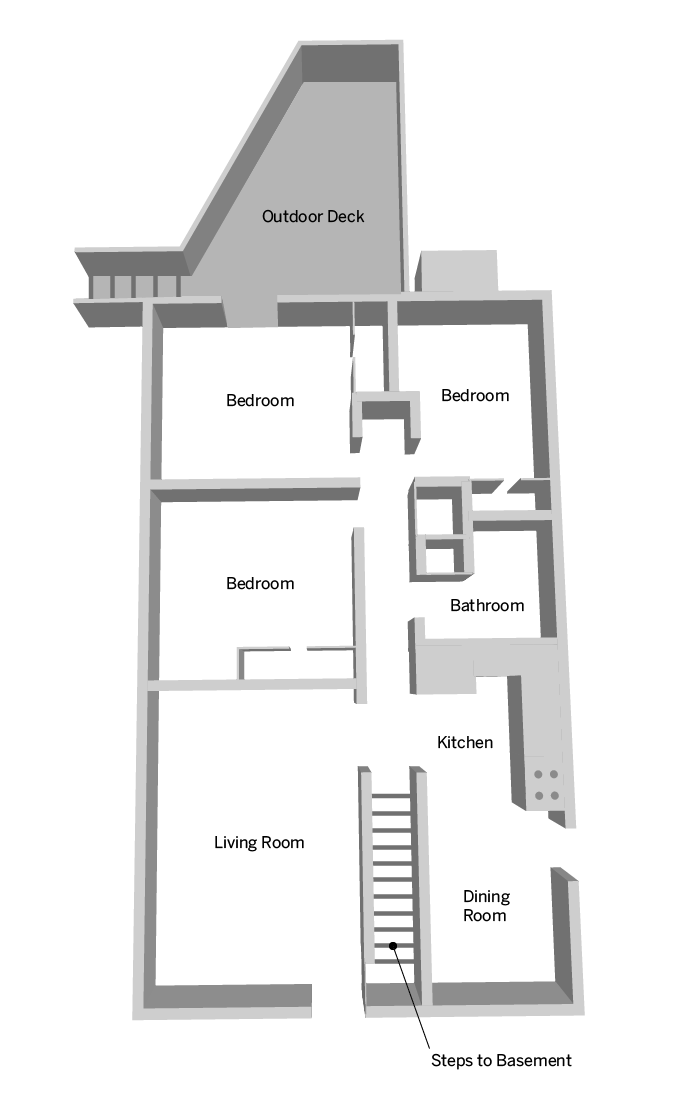

State and local fire investigators would spend months sifting through the wreckage, examining smoke patterns, broken windows, the electrical system and appliances, and the charred remains of furniture. They finally concluded in a report issued late last month that the cause of the fire could not be determined. But in more than 20 pages of detailed findings, the report begins to sketch a hazy picture — with a few clues, and some confounding questions — of those terrifying minutes inside the house on Colonial Road on the evening of Jan. 26.

A dedicated father

It was Ed Lorenzen’s devotion to his children that had brought him to the house in Coventry.

He purchased it in 2015, soon after his marriage ended and his wife and three children left Maryland and moved to Rhode Island. By necessity, he continued to live near his job on Capitol Hill. But he was determined to remain a presence in their lives.

The Rhode Island house was small and in a modest neighborhood. It was near a lake with a beach, and it wasn’t far from where the children lived with their mother. Once a month, Lorenzen made the long drive north and stayed there for 10 days, working remotely while spending time with his kids.

It couldn’t have been easy, balancing a high-pressure career and three young children 400 miles away, but friends and colleagues said Lorenzen rarely spoke of the strain. Indeed, he stood out on Capitol Hill as an unusual breed, known both for his encyclopedic knowledge of budget policy — which made him an essential resource for legislators, aides, and journalists — and for his tireless patience.

“The hours he put into helping people understand the issues was kind of unheard of,” said Marc Goldwein, who worked closely with him at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the nonpartisan think tank where Lorenzen had been a senior adviser since 2011. “People came to rely on him, and I don’t think we even knew all the things he did. . . . The same attention he was giving me in the course of a day, he might have been giving 20 other people.”

His willingness to help reflected a deep kindness, those who knew him said, that infused everything he did. He was often the smartest person in the room, but he didn’t need credit or attention, and he was never condescending, said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

“He would ask the question that cut to the heart of the issue, or offer the technical explanation that eluded the group — and he did so in the most laid back, unassuming way, so as not to embarrass anyone,” Riedl wrote in an e-mail.

After years of undivided focus on his work — and years of quiet longing for a family, according to several people who knew him well — he had come late to fatherhood, in his 40s. He relished the role, and he reveled in his children.

He had adopted his wife’s son Zacheri after they married. Now the 12-year-old was a typical preteen, busy with video games, but he shared Ed’s love of baseball, and played skillfully. He was a gentle and indulgent older brother to the two young siblings who had come along: Penny, who delighted Ed with her sass, and Michael, fondly known as “Bug.” Michael, named for Ed’s father, had recently made great strides. The boy’s speech had been delayed by autism, his mother said, but now he was learning to ask for what he needed — saying “more milk, please” instead of simply pointing.

On the last Friday in January, Ed was wrapping up a week in Rhode Island. He would enjoy one more weekend with the kids before heading back to Maryland. That morning, Michael had a therapy session, and Ed went with him. Zacheri spent time at his mother’s house after school, and then, around 6 p.m., she dropped him at his father’s place in Coventry. He headed downstairs, to his bedroom in the finished basement. The 12-year-old had been there only about 30 minutes, watching TV, when he smelled smoke and heard banging upstairs, where he’d left his father and two siblings.

After he climbed to the top of the stairs and scooped up his sister, after he called out to his father and brother, fled the burning house and dialed 911 about 6:30 p.m., Zacheri Lorenzen called his mother, a family friend said. She sped back to Coventry from her home, approximately 30 minutes away, and arrived around the time the fire was extinguished.

It was about that time that firefighters found Ed and Michael in the living room, on the floor, six to eight feet from the open front door. The state medical examiner would determine that their deaths were caused by smoke inhalation and burns. The firefighters also found one more survivor: The children’s small brown dog, Muppet, was alive, having sheltered through the blaze in another room.

The fire was out. But the grieving, and the quest for a cause, had just begun.

What we know

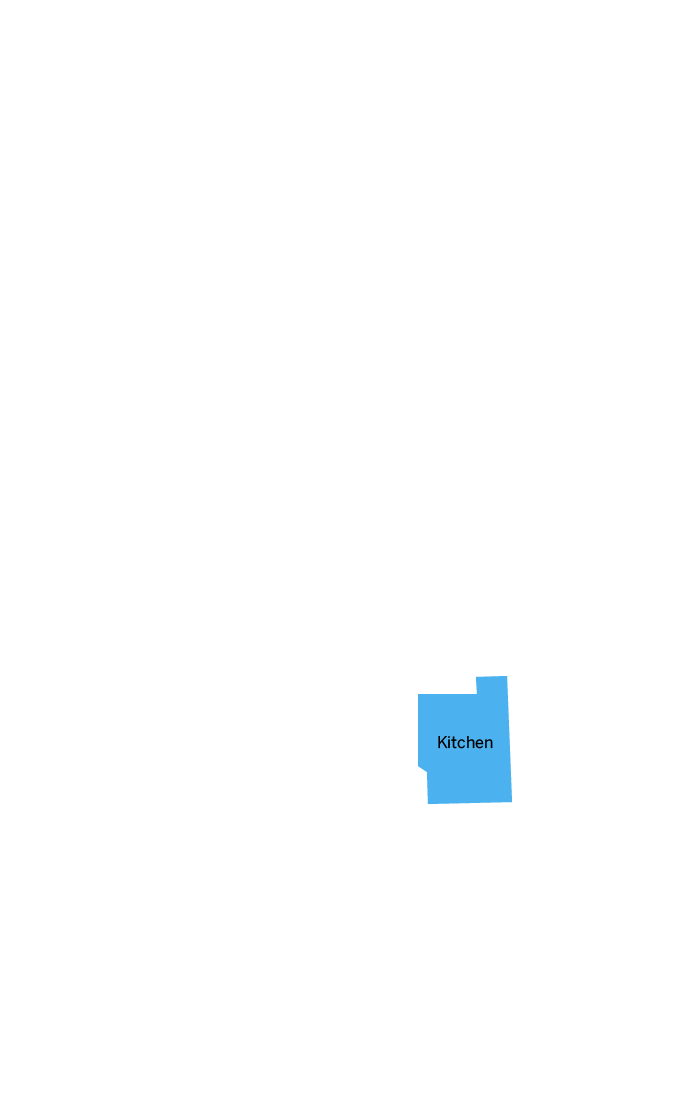

Studying the path of damage in the home, it did not take investigators long to determine that the fire had started in the living room and then spread into the adjacent kitchen. Extinguished before it could consume more of the house, it left heavy smoke damage in the hallway that cut through the one-story structure, and in the three small bedrooms.

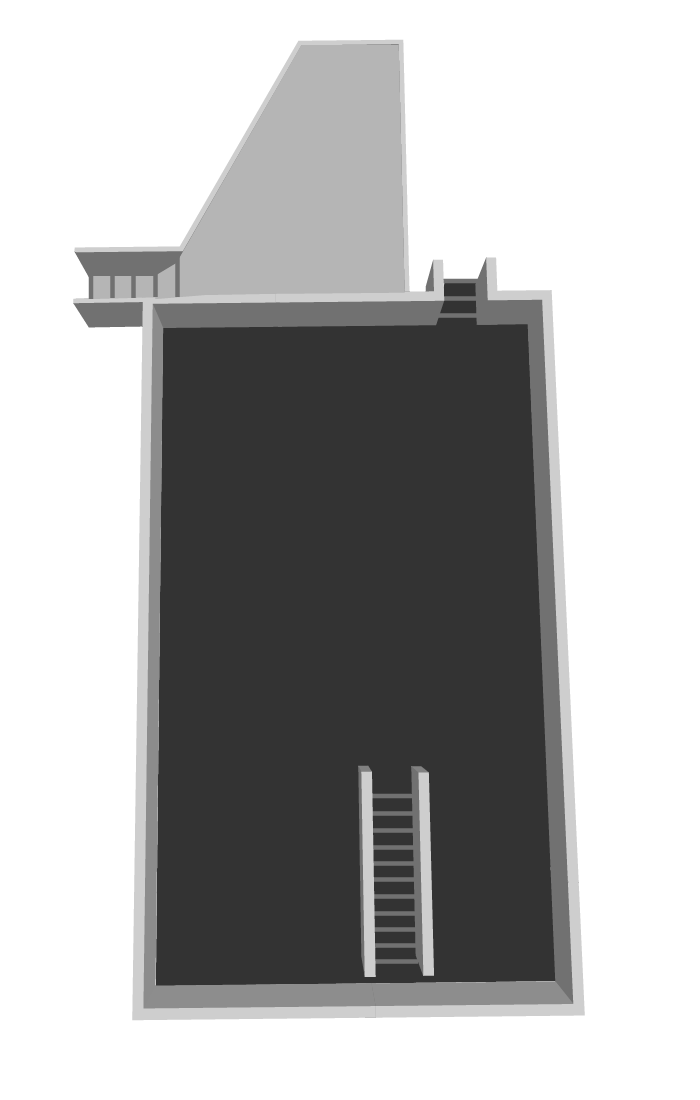

The path Zacheri took to escape the fire led down the basement steps, through the basement, and out the bulkhead at the rear of the house.

According to the fire marshal’s report, the living room was furnished with a couch and a recliner, two lamps, a TV, a coffee table, and an end table. A laptop computer likely rested on the end table next to the recliner, plugged into the wall. Children’s toys were scattered on the floor.

Here, in the ashes of a father’s last hours with his children, investigators tried to understand what had gone wrong. There was no fireplace, no woodstove, no Christmas tree to blame. Ed Lorenzen did not smoke, eliminating the most common cause of fatal house fires. Investigators brought in dogs trained to detect accelerants, but found no evidence the fire had been set. They ruled out the lamps, the TV, and the cable box as sources of ignition. But when it came to the laptop, their findings were less clear.

When investigators found the device, it was on the floor near the upended coffee table. It, like everything else in the room, had been damaged by the fire. But investigators could not tell for sure if the fire had attacked it from the outside or erupted from within it, due to a possible battery defect. The damage to the battery compartment was extensive; two of the computer’s battery cells had ruptured, and internal parts were found scattered nearby. In hopes of learning more — and pinpointing a cause — they sent the laptop for further tests, which could take months.

The laptop “is the last piece of the puzzle,” said John Dean, the chief deputy state fire marshal. “But right now it’s only a hypothesis.”

Investigators had other nagging questions.

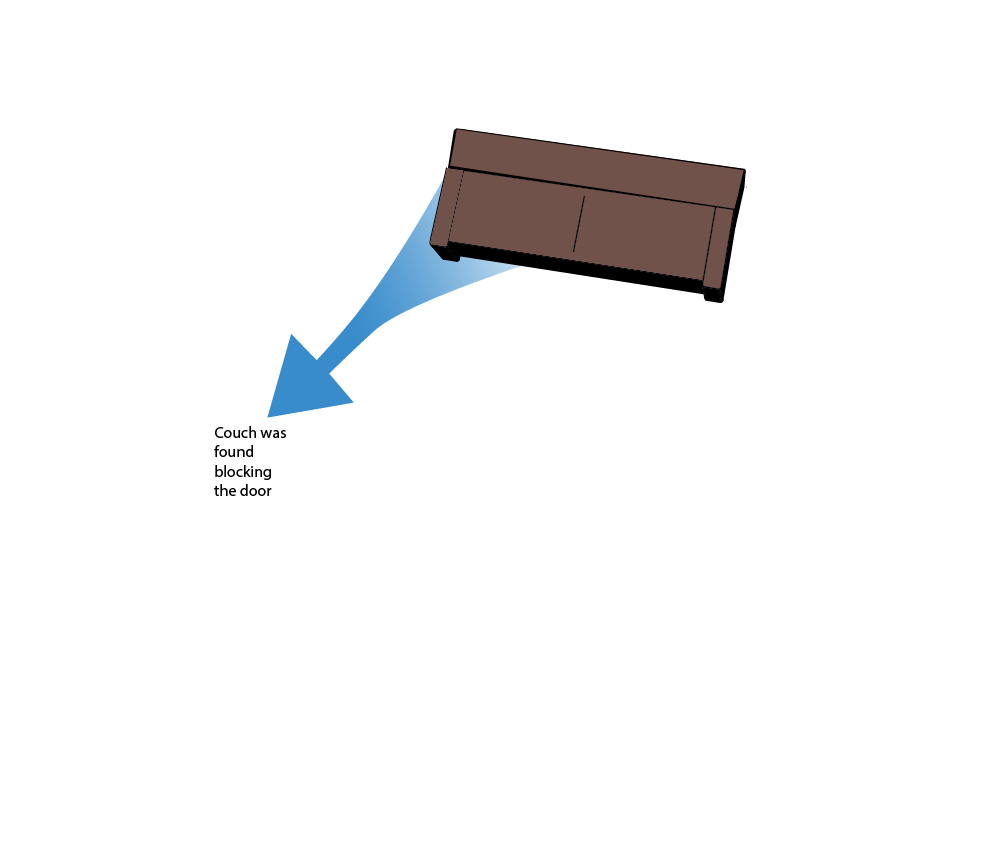

Why was the front door to the house open? It was that way when firefighters got there, either because someone had opened it or because it had been consumed by fire. And then there was the couch. It was blocking the front door when firefighters tried to enter. They would later determine, through interviews with witnesses, that the couch was normally placed across the room, against a wall.

Exactly when — and why — someone moved it, they have been unable to determine.

“Without an eyewitness,” Dean said, “any reason we could give would be speculation.”

Was it the laptop?

When the battery inside a laptop catches fire, it can send flames shooting outward, said two experts, one a chemistry professor at Northeastern University, the other a mechanical engineer at a forensic consulting company, ARCCA. If a couch sat close enough nearby, that initial burst of flame could ignite it, said the experts.

Once a couch or other furniture is burning, the window for escape diminishes rapidly. Modern home furnishings are made of materials that burn much faster and hotter than the furniture of the past, experts said, and they are more likely to emit toxic, black smoke capable of producing blackout conditions in a room and quickly overcoming those who breathe it in.

Laptop Safety Tips

- Always use approved chargers or charging systems intended for use with your device or battery pack. Non-approved chargers or systems may not work properly with lithium-ion battery packs and can damage the battery or device, or cause a fire.

- Follow manufacturer’s instructions for charging. Don’t overcharge devices or leave them unattended for long periods of time. Overcharging can lead to a fire.

- Don’t charge or use lithium-ion batteries in extreme temperatures. Cold temperatures can cause a battery not to hold a charge while high temperatures (or prolonged exposure to sunlight) can cause a malfunction and lead to a fire.

- Replace and properly discard damaged batteries. Using damaged batteries may lead to thermal runaway which can cause a fire.

- Don’t place charging devices or devices in use on soft and/or combustible surfaces. The heat produced by the charging or use of the battery can get trapped around the battery and if left untouched, can damage the battery or device, or cause a fire.

SOURCE: Massachusetts Department of Fire Services

“It used to be you had 15 minutes to get out of a house fire,” said Jennifer Mieth, a spokeswoman for the Massachusetts Department of Fire Services. “Today, it’s about three.”

Some misread the urgency when spotting a fledgling fire and make a fateful decision to fight it themselves — a leading cause of fire injuries, and an impulse seen more often among men, said Mieth.

The fire experts who spoke to the Globe offered general observations, not in-depth analysis of the fire in Coventry. It is impossible to know how Ed Lorenzen reacted to the fire in his home. But it is not uncommon for a panicked resident, suddenly confronted with flaming furnishings, to try to get them out of the home. State fire officials said people often react to burning mattresses that way, wedging them in doors and windows as they try to shove them out.

The logic seems sound: Push the fiery object out of the house; solve the problem. But in the act of opening a door or window, the homeowner only makes the problem worse.

“Fire is a breathing entity, and requires air to maintain and grow,” said Daniel McDonough, an engineer with ARCCA. “If a fire is in the growth phase and there is plenty of fuel, opening a door would provide more air and allow the fire to grow more rapidly.”

Friends of Ed Lorenzen, left yearning for answers after his death, said there was one thing they were certain of: The father who had waited so long to know his children would stop at nothing in his efforts to save them.

And when he could not, his son Zacheri stepped in. Hailed as a hero for saving his sister that night, the 12-year-old said it was a simple act of love.

“Ever since she was born, I’ve loved her with all my heart,” he told a Rhode Island TV station. “I would never let anything bad happen to her.”

Tragedy upon tragedy

Ed Lorenzen had known tragedy since he was a child. His father, Michael C. Lorenzen, took his own life when Ed was young. Years later his mother, Barbara Houghtaling, was permanently disabled in a car accident. Ed shouldered responsibility for her care, driving back and forth from Washington to Pennsylvania.

He carried his burdens without fanfare, his friends said, and tried to use his experience for good. After his mother’s accident, he testified before Congress about the importance of federal aid for disabled people. He helped raise money for suicide prevention, and tried to ease the stigma around mental illness, talking openly about his father’s death and the importance of mental health care.

When the opportunity to have his own family came, he did not hesitate. He proposed to his wife, Kellie, and her young son, Zacheri, together, on a baseball field, friends said. As his new family grew, with the births of two more children, he tempered his workaholic habits.

Lorenzen’s leap into fatherhood “was like the fulfillment of a long quest,” his close friend Chuck Blahous said. “Ed was a family guy for a long time before he had a family of his own.”

Fire investigations, though increasingly advanced, are often no match for a fire’s destructive force. In Massachusetts in 2016, according to the most recent data available, investigators were unable to pinpoint a cause in nearly one-third of all fatal residential fires, according to the state Division of Fire Safety. In 2015, 40 percent of fatal house fires had no determined cause.

To some who pine for clarity, the lingering questions in Coventry feel like an affliction. But to Kellie Lorenzen — grieving for her little Bug, who loved to snuggle — the cause of the fire never seemed important.

“No matter what they find and when they find it, it won’t bring my baby back,” she wrote by e-mail.

Jenna Russell can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @jrussglobe.

To learn more about efforts to support the family, go to this page.

Submit a comment for this story

Credits

Design by Amanda Erickson

Development by Kevin Wall

Story edited by Steven Wilmsen/Globe Staff

Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel/Globe Staff

Audience Engagement: Heather Ciras and Katie McLeod/Globe Staff