In search of sanctuary

The pews grew emptier and emptier. Until at last they realized: the Congregational Church of West Medford was dying. But they were people of faith and they believed in resurrection. For two years, this is what they have looked for.

Medford

It is a bright Sunday morning at the end of September 2014. Cars whiz past a stone Gothic Revival church on High Street.

Inside the sanctuary, sunlight filters through ruby and sapphire stained glass. Twenty-eight people sit in the pews, waiting.

The minister, a woman in late middle age with tousled hair and tattooed feet, summons the congregation to the front. Those who have keys to the church surrender them, dropping them with a plink into an aluminum colander. Everyone takes an object — a Bible, a candle, a cross.

They sing a final hymn, “Now Thank We All Our God.” In the clock tower, the bells clang 11 o’clock. The people pray and then walk back down the aisle, out the front doors, into the brilliant morning.

Squinting in the sunshine, they file two blocks down the sidewalk to West Medford Square, a strip of shops straddling the commuter rail tracks. They stop at a storefront wedged between a deli and a nail salon. A banner over the door proclaims, “Sanctuary United Church of Christ.”

Inside, looking out the plate glass windows, they can see an old-fashioned hardware store across the street, a faded computer repair shop. A bus huffs by.

They share Communion, then a celebratory brunch — fruit, muffins, mimosas.

“Here we are,” someone says, raising a glass. “Hallelujah!”

This moment has been coming at them for months, years, a generation, longer.

Here they are. Hallelujah.

Now what?

The Congregational churches that shaped New England are emptying out. Built by the Puritans and their progeny, these self-governing congregations were an incubator of early American civic culture, the anchor of every town square.

In Massachusetts, the United Church of Christ, the largest Congregational denomination, saw 22 percent of its membership die or drift away in the last decade, continuing a slow collapse that began in the 1960s.

Church leaders are racing to find ways to reverse the exodus, to restore vibrancy to their brand of progressive Christianity in an increasingly diverse, secular, and polarized society. Some congregations are taking extraordinary steps to reinvent themselves.

The Congregational Church of West Medford was near death. Could it be revived?

A half-century earlier, the church, set back from the street and half covered with ivy, was packed to the balcony on Sunday mornings. The Sunday school teemed with children, 185 of them. The congregation’s life together spilled over to weekdays, filling the calendar with sewing circles and retired men’s luncheons, junior high dances and junior choir practices, meetings of the Cub Scouts and the Women’s League and the Deaconness Board and the Couples Club.

To Kim Hartnett, a shy 5-year-old with crooked bangs, the church’s gruff stone face was permanence itself. Its massive front doors looked like the entrance to a castle. The pipe organ’s groan vibrated in her ribs.

On Sunday mornings, Kim sat in the pew next to her mother, her gaze wandering among the women’s hats and up to the stained glass. The weight of the burgundy Pilgrim Hymnal felt solemn in her hands. When the minister droned on, she would flip its delicate pages to her favorite hymns: “We Gather Together,” “Faith of Our Fathers,” “All Things Bright and Beautiful.”

Sometimes during coffee hour, she would meander downstairs to the Sunday school wing. Peeking through a narrow window of a closed door, she could see men in suits sitting around a long table, smoking and counting the offering money.

Her mother, June, had married just out of college; they settled into the first floor of June’s parents’ two-family house in West Medford and joined the Congregational church in the late 1950s. They had two boys and then Kim, the baby.

The Congregationalists’ democratic polity suited June, an angular, exacting woman. In the Congregational Church, you did not take orders from bishops and priests. You voted. The minister worked for the people, not the other way around.

The church’s roots extended another century back, to 1864, when Rachel Barnes opened a Sabbath School in her house for children on Medford’s west side, as large estates had begun to be subdivided and sold for housing. Near the turn of the century, there was a congregation of 125 and a grand church building. A fire burned the church to the ground in 1903; the next year, construction was completed on a new building at High and Allston streets.

Church suppers marked the seasons as reliably as the liturgical calendar — the fall ham and bean supper, the turkey dinner on Veterans Day, the January mother and daughter banquet, the Easter breakfast, the spring lobster luncheon, the June picnic.

June’s husband drank. The marriage foundered. The young women’s group at church, Circle 5, embraced her, taking her to movies, out for walks. But June was adrift.

Her father sat her down one day: You can do anything you want to do.

And so June opened a photography business, taking freelance assignments for the Medford Mercury. She drove an old Ford Falcon, hewing to the bus routes so she could get to where she was headed if the car broke down.

Yet she always found time for church. She helped at the church fair, an elaborate event the church women prepared for all year. She was one of 12 deaconesses who visited the sick and shut-ins, and who served as a kind of congregational smoke detector, alerting the minister when someone needed pastoral attention.

The church’s membership began to shrink in the mid-1960s, slowly at first.

Still, for the next 30 years, the Congregational Church of West Medford was the “eatingest church in town.” June loved to pour coffee and talk politics when the mayor came to “June’s church,” as he called it, for a church supper.

“Luckily,” the mayor quipped years later, “I was on June’s good side.”

Kim, who by then had married a police officer, Jimmie Grubb Jr., and was raising three children, taught Sunday school. She loved to return each fall, running off new attendance sheets for the teachers, arranging the Bibles on the classroom bookshelves.

But soon, there were more Bibles than children.

Older members died or moved away. Young families would join the church and then, a few years later, leave for suburbs with better schools. Immigrants trickled in with different religious traditions.

The larger culture was changing, too. Attending a church or synagogue was now more of a choice than an expectation. You used to have to explain to the neighbors why you didn’t go; increasingly, you had to explain why you did.

June was frustrated. Church suppers were a lot of work. Where were the younger women?

Most of them found the notion of a ladies’ circle prehistoric. They didn’t have time; they had jobs as well as kids to take care of.

“So did I,” June would reply tartly.

Kim tried to follow her mother’s example. On Easter morning, she had her kids down to the church by 7 a.m., the girls in hats and gloves, her son in a tie. She would flick on the lights in the kitchen. In a few minutes, sausage was sizzling, the huge coffee pot was perking away. In those moments, she felt peace. She belonged.

But the old traditions kept fading. A favorite had been the candlelight service on Christmas Eve. At exactly midnight, everyone stood in the darkened sanctuary, holding vigil candles, and listened to the church bells ring in Christmas Day. Then they all sang “Joy to the World” together.

As the years wore on, attendance grew sparser. Ministers went on too long, talking over the bells. Something was lost.

Paul Roberts had never meant to become the church moderator. He had never intended to join a church at all.

A towering man with mirthful eyes and a disarming wit, Paul grew up in Illinois, the son of a minister whose divided congregation was known for giving its pastors heart attacks. Paul’s dad had two.

Paul wanted none of it. He came east to become a history professor. The academic job market was bleak, so when he and his wife, Julie, an elementary school art teacher, decided to start a family, he abandoned his dissertation for a corporate job.

They loved tramping through fields and woods. They began learning about the birds they saw. With Paul, interests became obsessions: Soon, he was running a local hawk-watching group, editing a birding magazine.

Religion for Paul was the shimmering afternoon at Wachusett Mountain in 1978 when he saw a river of 10,000 broad-winged hawks in migration, a twirling kettle of birds riding a warm updraft several thousand feet aloft to catch the high northeasterly winds. They were small as iron filings in his binoculars, wild, mysterious, soaring at the edge of the visible world.

He was off birding on the Sunday morning in 1984 when Julie first walked up to the stone church on High Street, 5-year-old Laura trotting along beside her, Becca bundled into a Snugli. Julie was not particularly religious either, but she wanted to feel more at home in Medford. She thought the girls should go to Sunday school. She wanted to help other people somehow.

She was surprised by how welcoming everyone was. A few weeks later, at the cleaners, a seamstress looked up with a smile.

“Oh, aren’t you coming to our church now?” she said.

The minister, a young fellow, kept asking Julie to bring her husband. One day in the late 1980s when Paul was home sick from work, the pastor came knocking. Eventually, Paul made his way over.

“You’ll either get exasperated and leave,” Julie predicted, “or overinvolved.”

Paul soon found himself on the committee that assigned people to positions in the church’s volunteer bureaucracy. When he read the annual report, he discovered the church was draining its endowment to pay the bills. The cavernous building needed repairs every year. Heat cost tens of thousands of dollars every winter. The offering could not cover it.

Max Beal, a respected businessman and church leader, warned the congregation: It could not go on like this. People seemed to understand, but there was no sense of immediate crisis. They had always managed.

Paul, though, was listening closely.

The church’s minister and his wife — who at first worked as a salaried minister, then as a volunteer — threw themselves into driving up membership, even undertaking doctoral research in church growth and trying to apply what they learned. They created a social group for divorced people after a demographic survey revealed a trove of middle-aged singletons. But deaths and departures outpaced new arrivals.

Anxiety bred discontent. In the mid-1990s, a quiet plot to oust the ministers collapsed, and the subsequent furor roiled the congregation. The moderator — the person in charge of running congregational meetings and the church council — resigned and left. Paul filled in.

Several years later, he helped lead a capital campaign that brought in more than $150,000. But the mainline church was a melting glacier, splitting and dissolving into the sea; in Medford and Cambridge and Arlington, around Massachusetts and across America, pews were emptying, churches were closing.

By the early 2000s, average Sunday attendance had slipped below 60. The West Medford church was hurtling toward financial ruin, Paul knew.

Then an elderly congregant died. Everyone thought she was a pensioner. She left the congregation more than $1.5 million.

The End of Days was postponed.

But the conflicts continued, exposing a divide between people who had been there for decades and more recent arrivals. In 2005, the church council advised the clergy couple to begin searching for a new church. They were already looking.

After they left, the infighting metastasized. An interim minister and associate minister clashed about how to lead the church forward. The congregation split into factions. Some people stopped speaking to one another, avoided one another’s eyes at coffee hour, even the passing of the peace.

Don’t go there, that’s Satan’s church, a clergy friend warned. They’ll kill you!

We’ll see about that.

The Rev. Steven Savides was in his 30s, just out of divinity school, a former journalist from South Africa who’d come of age as apartheid was crumbling. Resolving congregational conflict was his intended specialty.

He arrived at the West Medford church in 2008, preaching reconciliation. These were good people, he thought, who had fallen into discord under the pressures of declining membership and an outdated, bureaucratic structure that invited division.

He had the congregants face one another across the center aisle, lift their hands, and bless one another. He cordoned off part of the Sunday service to invite the congregation to pray out loud. If someone’s brother was dying, he reasoned, the community should know.

June would invite the young minister to lunch. Over lobster salad or chicken sandwiches, she would ask how things were going, and then move crisply through her own agenda, a mix of news and criticism. Her solution to the church’s decline was always the same: “Let’s do another dinner.”

New people arrived, like Carvina Williams and her 9-year-old twins, Tripp and Drew Hill. Her husband, Ed, had just died of a long illness. Kim Grubb, the boys’ former preschool teacher, was a friendly face.

Church gave Carvina a spiritual charge that helped her survive those early, wrenching years alone, and gave her boys a faith community of their own. The pastor helped her grieve, encouraging her to find quiet time to sit alone and experience the pain. Ed, she thought, would have liked this church.

The congregation began to knit itself back together, as Steven helped them focus on spirituality, prayer, and Bible study. In 2012, they scrambled two dozen people for a mission trip to Pine Ridge, an Indian reservation in South Dakota. The mission was like a defibrillator to the heart of the congregation, shocking it to attention: Being Christian required helping others; it meant living Jesus’ teachings in the world.

Average Sunday attendance ticked up, from 40 to about 60. But it was not nearly enough to pay the bills. Merger talks with another church failed.

By the late summer of 2012, Steven Savides felt he had taken them as far as he could. He found another job with a thriving congregation in Connecticut.

Paul heard about a program the United Church of Christ was trying. “Crossroads,” as it was called, was designed to help dying churches decide their fate and maybe reinvent themselves.

A blue Ford Escape hybrid pulled up to the side door of the church on a cold, dark evening in December 2012. The woman in the front seat — late 50s, russet-brown hair — turned off the engine.

The Rev. Wendy Miller Olapade was despondent. Recently divorced from the father of her younger son, Aaron, then 12, she was living in a friend’s three-room apartment in Needham with Aaron and her older son, Alexander, 19, who was on leave from Harvard. She had been turned down for 10 jobs in a row. To pay the bills, she was working part time for a lawyer friend in Worcester.

“Jesus is saving you for something,” her spiritual director promised.

Wendy found religion as an adult through 12-step programs in church basements, getting sober at age 32 after a wild booze- and drug-filled decade of working in corporate sales. She wandered into a Lutheran church, the denomination she occasionally attended as a child in Pennsylvania. Lutherans preached grace, the idea that the love of God is a free gift for everyone, saints and sinners alike. When she first tried Communion again, she felt it: God’s overwhelming love.

But as a seminarian at Boston University, she became pregnant with Alex. His father was out of the picture. She rejected the Lutheran bishop’s suggestion that she pause her pursuit of ordination. The United Church of Christ welcomed her in.

She married a part-time minister at Myrtle Baptist Church, a historic African-American congregation in Newton. Aaron was born in 2000. After nearly six years serving as senior minister at a large church in Reading, she became an interim minister, specializing in helping churches through transitions. But her marriage had fallen apart, and now she wanted to be settled, if only for Aaron’s sake, as his high school years loomed.

The West Medford job offered a $40,000 salary, plus health care, pension, and a parsonage in a lovely neighborhood near the church. The minister who oversaw the Crossroads program in Massachusetts thought Wendy’s comfort with multicultural ministry could be a good fit in West Medford, which was home to a storied African-American neighborhood and a small influx of immigrants. And she had a knack for drawing people in.

It would be the new pastor’s job to lead the West Medford church through a period of deep reflection, and then they would vote on their future. After that, no guarantees.

Wendy let herself imagine the possibilities.

What could she do here if she had the chance?

Inside the West Medford church, the air was stale. As she walked in for her job interview, her eyes scanned the fusty parlor.

And yet. She looked around at the faces of the search committee: Instead of denial, they were choosing exploration. They might be ready to try something interesting.

All her life, Wendy had been told she was too much, too bold.

Maybe Jesus was saving her for this.

In March 2013, a bearded church consultant flew in from Iowa. He toured the church from the boiler room to the bell tower. He met with the church’s financial officers. Then, he and Wendy climbed into Paul’s gray Hyundai for a tour of Medford.

In the evening, the congregation met to talk about what they liked about their church. Nineteen people showed up, including Kim Grubb.

She understood the financial picture. She now helped oversee the small army it took to maintain the church: the plumbers and the slate roof specialists, the electricians and the snowplowers.

When people said the church is the people, not the building, she got the point.

But to Kim, the building mattered, too. God was everywhere, but her life with God was here.

She decided not to come to any more of these meetings. She knew she would try to hang on to what was.

And her mother needed her. June had been diagnosed with bladder cancer.

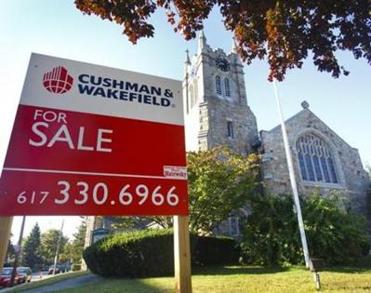

The congregation broke into three groups and began meeting in one another’s homes. Nearly everyone understood they had to sell the church. There was no time to try to grow back into it. They could survive for maybe two years with what was left in the bank.

What happened next Paul would later call “an unscheduled emergence of powerful forces.”

People talked about the mission trips to South Dakota. They talked about their love of music, art, praying together.

What if they could build a church around those things? Other progressive churches had found a way forward in a changed world. What if they no longer had to pay for the building? Wendy’s energy and creativity lifted them. They began to imagine a future.

They set a vote for November on how to move forward. By the time it came, it was a foregone conclusion: They would sell the church and try to start something new together.

But what?

They scouted nearby experimental churches, sending someone to visit a congregation that had sold its church and moved into a house, someone else to a Christian community in Boston that fingerpainted on some days and sang Gregorian chants on others. They watched a video about a church in Brooklyn that worshiped during a weekly communal meal in a storefront, and another about a Lutheran coffeehouse near Seattle that served up food, beer, and free arts events.

It was hard for Paul to imagine any of it. A Christian coffeehouse for hipsters? He looked around at the earnest collection of social workers and teachers, artists and administrators, hardly a one between the ages of 15 and 50. Not likely.

Kim was watching from a distance. June had stopped going to church almost entirely. She was ill, but she was not a fan of Wendy, either. According to what June told Kim, things went south on the day Wendy called to say she wanted to come by and visit. June said it wasn’t a good time, but Wendy had insisted.

Wendy cannot remember anything like this happening. She would never insist on talking with someone at an inconvenient time, certainly not a cancer-stricken elderly woman.

In any case, June would have little to do with the pastor after that.

A cold, wet morning in April, Palm Sunday 2014.

From inside the church office, Kim can hear murmured prayers in the sanctuary. She is tending to paperwork. The busywork comforts her, a distraction from the changes at the church and her mother’s decline, her sharpening cheekbones, her sunken eyes.

In the sanctuary, 30 members of the congregation bow their heads and pray aloud: For Brenda’s nephew, who will soon graduate from high school. . . . For Joy’s parents, who are moving this week. . . . For a man seen swimming at the Y, with the words “Drug Free” tattooed across his back . . . .

“Lord, in Your mercy.”

“Hear our prayer.”

Wendy gives the benediction. She is preparing them for Holy Week — and for a crucial meeting after church.

“The journey has to be traveled through Good Friday, through death, to get to the resurrection,” she says. “It is a violent and disturbing week, and the heart will literally be torn out of the universe.”

Afterward, the congregation lumbers into the chapel behind the sanctuary.

Wendy fires up her PowerPoint. She had gotten up at 5 that morning to finish it. Her plan came together around a discovery she made a week before, when the church’s realtor took her to see a shop in West Medford Square.

It was a florist’s shop. Just 1,000 square feet, but it had a beautiful exposed brick wall. And the location was perfect: right by the commuter rail station, with enough neighboring shops and restaurants to generate a little foot traffic. The landlord would let them have it for $1,650 a month.

Maybe this could be the perfect laboratory for all the ideas they had talked about over the last few months. Evangelicals had built thriving faith communities out of storefronts. Why couldn’t a progressive church start one here in Medford?

Wendy takes out the congregation’s newly adopted mission statement. “I’m going to preach it to you for a moment,” she says.

And then she lays out a proposal.

They would sell the Congregational Church of West Medford and move into the storefront. Develop a new website, a new sense of themselves, a new sense of what church could be.

They would rent space for Sunday worship from another church. During the week, they would be a sanctuary in the city at the storefront. A place where people could eat their lunch, use the free Wi-Fi, meet others in the community, talk with a pastor, sit in a quiet, meditative space.

The storefront would be a gallery for local artists, a gathering spot for spirituality book groups, faith and film discussions, beer-and-hymn sings, yoga.

“The possibilities are only limited by the number of hours in the week,” she said.

Building on their passion for the Pine Ridge mission, they would become a hub for local community service.

“People are desperate not to come to church, but to have meaning and purpose in their lives,” Wendy says.

Rather than burn through more than $10,000 a month keeping up the building, they would spend that money — using the proceeds from the sale of the church — on staff to help build a new congregation.

She stops. “Do you feel overwhelmed or excited?”

“Excited,” someone says.

It is true. Some remain stone-faced, but many more look as if they have awakened from a long sleep. There is nervous chatter.

They would have measurable goals, Wendy says, so that “if it ain’t working, we can stop.”

As the meeting ends, Paul looks at the faces around the room.

“I don’t think we are the church we were an hour ago,” he says.

Easter Sunday 2014 is their last one in the old stone church. They share a modest potluck breakfast. Young adults who have grown and moved away are back home visiting. The few children frisk about in the cold grass, hunting for plastic eggs hidden around the bare-limbed cherry trees.

At the end of the service, the congregation stands and sings the Hallelujah Chorus of Handel’s “Messiah.” There are more than 60 people in the sanctuary, and it is glorious.

The Gospel text the following Sunday is about Thomas, the disciple who did not believe Jesus was raised from the dead until he touched Jesus’ wounds with his own hands.

Jesus tells Thomas: Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.

After church, the congregation talks over lunch. The final offers for the church are in. The best are not from developers, as many expected, but from other churches: Seventh Day Adventist, Southern Baptist, Evangelical, Pentecostal.

Wendy says: “How are you feeling today about it all?”

The church bells ring.

The congregation assembles on the first day of June for a string of final votes.

They agree to sell the church to the Evangelical Haitian Church of Somerville for $2.9 million. The vote is unanimous.

But should they go through with their plan to move to the storefront? There is tight-throated anxiety around the terms of the lease and about how often they will reevaluate their experiment to be sure they do not squander money on a failed project.

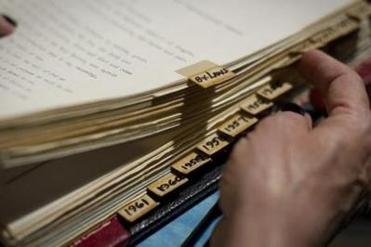

Kathy Williams, the church historian, speaks. She reminds them that the founders of the Congregational Church of West Medford had little but their faith when they started, sacrificing to build the first church building. When it burned down, they rebuilt.

“Those are our ancestors,” she says. “That’s what we’re made of. It’s been over 2,000 years since Jesus Christ was born, and there is still enormous injustice in the world. The work is still here for us, every single day.”

The vote to move to the storefront is 45 to 1. Kim does not vote. The lone dissenter, a close friend of Kim’s, leaves in tears.

The last full worship service before the move is like a wake. Everyone takes turns sharing memories.

One woman begins: “It was the people who kept me here. . . . Kim, Carol, Debbie, Julie. We could almost finish each other’s sentences.”

The congregation’s oldest member, who is in her 90s, is weeping.

“She says she loves you, but she can’t speak,” Wendy says.

They talk on and on.

I sat here and I experienced sanctuary and respite. . . . I remember my daughter twirling in her Easter dress. . . . I remember her pointing out the window: ‘There is my church.’ . . . Every year there was a play with kids, and one year Jamie was Moses. I remember him parting the Red Sea. . . . You all accepted me for who I was. You never judged me.

At last, they are silent. Wendy waits a long moment.

“And we offer You the memories we keep deep within ourselves.”

High overhead, the ceiling fans whir.

A stubby blue-and-white truck marked 1-800-GOT-JUNK? sits by the church’s side door. The new owners will keep most of the furniture. The men work quickly to load what cannot be taken along.

There are Post-It notes on everything, marking what should stay and what should go: sewing machines the church owned for the ladies’ all-day sewing circles. An ancient microwave. A broken toilet. A pine cone wreath.

Slides and film strips with neatly typed labels. A basket of used vigil candles. A painting of pilgrims, trudging across a snowy bluff overlooking an icy sea.

June’s hospital bed is in her pine-paneled den, positioned so she can look out the picture window facing the street. One wall is covered with family photos. Church women come to visit, Julie Roberts with casseroles, Brenda and Jenny Briggs with the chocolate chip cookies June always loved at coffee hour.

Kim worries about where they will have the funeral. The church sale is supposed to close Sept. 30.

She and June talked about it over the summer. Maybe the Baptist church, June said, half-heartedly.

The nights cool, and then the days, as September wears on. June is still fighting. Kim talks with Wendy about asking the new owners if they could rent out the old church. The pastor assures Wendy this would be no problem.

Kim tells her mother, It looks like we’ll have the church.

June stops eating. She stops talking. The church closing is delayed a week.

On Sept. 27, Kim leaves the house briefly in the late morning, for a trip to Rite Aid. When she returns, she hears a rattling sound in June’s lungs.

June breathes a few more times. And then the only sound is the breathing of the hospital bed, the soft hiss of the automatic mattress inflating slightly, deflating slightly.

“Mom?”

Kim adjusts the bed. June is still.

Kim cries out.

“What am I going to do without you?”

Kim needs a pastor.

She calls Wendy, who comes quickly and wraps Kim in a hug. Wendy kisses June, sits beside her, takes her hand, and prays.

June’s funeral is the Saturday after the move. The Congregational Church of West Medford’s final gathering at the old stone church.

Kim gives the eulogy. The ache is so strong in her she can barely keep her voice from breaking. She must get through it. June would not have wanted anyone but her to do it.

“I feel grateful,” Kim says, “we could be gathered here.”

Her eyes drift toward the balcony, where she used to sit as a girl under the great stained glass window with Jesus and the Old Testament prophets. She feels her mother’s presence.

June might not like to see Wendy officiating. She would be disturbed to learn about the plans for dinner afterward at Bocelli’s, where Kim had gotten a good deal on a private room. June never cared for Italian food.

But peering down on the old sanctuary, Kim knows, June can see the Wescotts. The Luongos. The Robertses. Max Beal, a fresh posy on his lapel, and his wife, Mary, June’s dear friend, and one of the last surviving members of Circle 5.

And June, Kim feels sure, is well pleased.

It is late on Christmas Eve, spitting rain. PEACE ON EARTH glows in colored lights at Medford City Hall. Down High Street, the Congregational Church of West Medford is dark and silent.

In West Medford Square, Santa and Mrs. Claus dolls rotate silently in the window of the Paul Revere Restaurant. Across the street, Sanctuary is lit up.

Wendy’s laptop, connected to the storefront’s new sound system, is blasting Christmas music: “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire. . .” In the window are poinsettias and a small creche, alongside Wendy’s deconstructed Christmas tree — a tree-shaped mobile made of sticks and string. Wendy has put out trays of cookies and cheese, and wine and hot cider on a side table.

Thirteen people show up, all familiar faces except for a tall man wearing a pea coat, a barber from the neighborhood who has just lost his shop.

He has not been to a Christmas Eve service since he was a boy. He plops down in the back corner, drinking merlot, scarfing cheese and crackers. Then, he sits back and stares into the middle distance.

“Welcome, everyone,” Wendy says. “Bless you for trying Sanctuary on Christmas Eve. It’s going to feel different. I hope it will feel like a blessing.”

The service begins, a mix of prayer and carols sung to recorded music and the whoosh of traffic outside and the clang of a passing train. Wendy tries to get the congregation to sing “Dona Nobis Pacem” in a round. She has complicated matters by adding an interfaith twist to the Latin lyrics: Asalaam alaikum ; Sim shalom, tova uvracha .

“The song in the air is a song about yearning for peace,” she says. “And pitch, perhaps.”

She smiles. Her voice warms them.

“Our prayer tonight is for peace for all people,” she says. “Between and among all peoples.”

They read from Matthew. They sing “O Come All Ye Faithful.” The prerecorded music is hard to follow. Finally, Wendy switches it off.

“Let’s try this by ourselves.”

And so they sing “Joy to the World” a cappella, holding candles in the darkness.

Wendy, bundled in a gray faux-fur coat, stands on the sidewalk near her storefront church in West Medford Square, holding a blue ceramic bowl of ashes.

It’s 7:45 a.m., near the midpoint of the snowiest winter in Massachusetts history. The temperature is in the teens. Snow smothers the rooftops, swallows garbage cans. Frozen waterfalls strangle the eaves.

“Ashes-to-go for Ash Wednesday?” she asks the few people who trudge past, offering to smear a cross in ashes on their foreheads. Most everyone keeps on walking.

Wendy would give anything right now for a real sanctuary. Lent, the period before Easter marking Jesus’ 40-day fast in the wilderness, is usually when she feels most confident as a pastor. Ashes, palms, bread, darkness. It all leads to the resurrection: Christianity’s beating heart.

She can tell that story in a church. Out here on the sidewalk, she feels ridiculous.

A few hours later, she is back at her desk at Sanctuary, staring at her computer. She is fighting tears; she does not want to go back out there. But then the Rev. Thomas Hathaway, Sanctuary’s part-time minister, materializes in his tall boots and parka, ready to join her for Ashes to Go, Round Two.

So Wendy picks her way again through the mealy snow. Pain pulses through her bad hip.

As she crosses the commuter rail tracks, a haggard man stops her. He nods toward her bowl of ashes.

“You don’t have to go to church for them, eh?”

She stops. “Would you like some ashes?”

He studies the white clerical collar peeking out from her coat. “You sure this is OK?”

She brushes her fingertips in the ashes and traces a cross on his forehead.

“Remember that you are from dust, and to dust you will return. God loves you forever.”

She inhales the icy air, the scent of wet pavement and sun-warmed snow.

At Magnificent Muffin & Bagel Shoppe, the women behind the counter regard her curiously.

“What are you doing? Ashes?” one says. “I’ll take ashes.”

Outside a bank, a woman pauses. “I haven’t in a while. Yes, please.”

Wendy is giddy with relief. She has something they want.

A sketch of Sanctuary’s proposed structure hangs in Wendy’s office, scribbled on large sheets of paper. It is a series of circles, each a small community to nurture: faith and arts. A monthly teen dinner. A group prepared to help neighbors in need.

A few events have already drawn small crowds. One blustery November night, people gathered in the storefront to sing hymns over beer and pretzels, conjuring up a rolling stream of old spirituals and solemn anthems as the wind blasted the plate glass windows.

Wendy has help — part-time ministers, consultants, advisers from the denomination. But the church secretary has quit, leaving her mired in minutiae, and Sunday attendance is slipping. There are four dozen official members, but only about 20 have come to church since the move.

“Well,” quips Paul Roberts, the co-moderator, “that’s eight more than Jesus started with.”

Many from the old congregation have left for a more traditional church. This was expected; an experimental church would not be for everyone. But their departure is like an amputation. Those who stay feel the absences acutely.

They had originally planned to borrow a regular church sanctuary for worship Sunday evenings, but the time change is too much of a metabolic shift. So they gather Sunday mornings at the storefront. The bright sunlight through the windows, the ceramic tile floor feels flat and antiseptic compared with the sanctuary in the old church. They sing to recorded music Wendy plays on the storefront’s sound system.

Children are scarce. Sanctuary has neither the space nor the energy for Sunday school. Wendy devises an alternative: a website to help families teach their kids at home. It doesn’t catch on.

So the congregation is a wounded thing, in no condition to look outward and find out what people in Medford want in a faith community.

Tensions arise over how to move forward.

Kathy Williams, who speaks with the attenuated drawl of a native North Carolinian who has lived all her adult life in Massachusetts, is worried about where Jesus fits in.

She was a vocal proponent of the congregation’s decision to sell the church and start over in a storefront. She believed Jesus did not want them to squander their resources preserving a fancy building. He wanted them to use their money — now vastly enhanced by the $2.9 million from the sale of the church — to spread the Good News and help those who are struggling.

She and Wendy don’t always agree on how to do this. Wendy thinks you don’t need to hit people over the head with Jesus right when they walk through the door, lest you confirm everything they suspected about Christians and scare them off. But Kathy feels Sanctuary must clearly distinguish itself from an art center or a social service agency.

She frowns when she sees Wendy has removed an array of nine birch crosses, handmade by a member of the congregation, from the wall in the storefront bathroom.

It was, by any measure, a lot of crosses for a bathroom. But to Kathy, taking them down was a symbolic mistake.

“It’s a Christian church,” she says.

Kim Grubb hasn’t returned to services since her mother’s death. She is overcome with grief but has also clashed with Wendy over the church’s after-school program, which Kim has overseen for years. And she’s upset when Wendy reacts angrily to the cost of the company Kim hired to plow the parsonage.

The snow finally melts. And then, a small breakthrough.

On a breezy March evening, about 60 people from Sanctuary and North Prospect Union, Medford’s other UCC congregation, gather at North Prospect for an experiment: Dinner Church.

In the church’s cheery basement, strung with white lights, they share Communion and a potluck supper, praying and singing and telling stories into the evening.

Wendy is preparing for the Maundy Thursday service, commemorating the night of Jesus’ betrayal and the final meal he shared with his disciples.

At the old church, Maundy Thursday was one of the congregation’s favorite services of the year. People seemed to need this ancient ritual evoking loss and abandonment. At the end of the service, the pastor stripped the altar, and everyone left in silence.

Wendy plans a service interwoven with a simple meal. Hours beforehand, she is at the parsonage, throwing the soup together. She rips open a bag of sliced vegetables. She grabs a butcher knife, hacks up some chicken, splits open a packet of dried noodles and chicken soup flavoring.

She dumps the lot into a crock pot, pops it into her Ford Escape, and heads to the storefront.

Every time she drives from her house to Sanctuary, she passes the old church. Today, pale light glazes its stone walls.

Should they have waited longer to sell? Maybe tried some of their new ideas in the old building? There wasn’t time, she assures herself for the 1,000th time. They had to move or die.

Nine people show up. It’s smaller than the actual Last Supper.

Instead of the traditional ritual of foot washing, in commemoration of Jesus washing his disciples’ feet, Wendy has bought hand balm. They take turns rubbing a little balm into one another’s hands. It is awkward, but tender. They eat their soup quietly.

Sanctuary’s front door opens. Kim is in the doorway. She has never missed a Maundy Thursday service. So here she is.

“Nice to see you, Kim,” says Dick Smith, a congregant in his 80s, his eyes crinkling.

“Nice to see you too, Dick.”

It’s sad, Kim is thinking. There’s almost nobody here.

Wendy snaps into hospitality mode, carrying a plate of fruit and cheese over to Kim.

Wendy asks everyone to share an experience of a memorable meal.

Kim remembers coming down to the doughnut shop in West Medford Square as a teenager, sipping coffee with her friends and talking the afternoon away.

“I thought you were going to say that the West Medford church was known as the eatingest church in town,” Paul says with a smile. “The turkey dinners . . .”

“The lobster luncheon, the finnan haddie supper,” Kim says.

Wendy interjects. June always thought it was the way to save the church, she says: “If only we could have one more dinner.”

Kim laughs a little, then looks down and sips her water.

Wendy says she realized something today: Dinner Church seems like a big innovation to them now. But how different was it from June’s beloved church suppers?

“It was easy to dismiss as something that was outmoded, that doesn’t exist anymore,” Wendy says.

“She’d be saying, ‘See,’ ” Kim says.

They share Communion and return to the Gospel.

Outside, it is dark. A bus whooshes by. Throngs of people pass outside, chatting as they leave Snappy Pattys, a restaurant on the block. Tears slide down Kim’s cheeks.

The young musician Wendy has hired to play the keyboard tonight begins to sing, in an agonized falsetto: Were you there when they crucified my Lord?

The tiny congregation joins in softly.

Wendy blows out a final candle. They sit in near darkness. The red EXIT sign throbs over the doorway.

They leave in silence. Paul touches Kim on the shoulder as he goes. Wendy kisses Kim’s cheek, hugs her. Stiffening a bit, Kim hugs Wendy back before turning to leave.

Good Friday is flat and gray. Clouds of sparrows alight on the rooftops.

This afternoon, Sanctuary is open as a meditative space. A recording plays monks chanting to acoustic guitar music. Wendy’s laptop projects images of art from across the world depicting Easter scenes.

Wendy sits outside on the sidewalk, inviting in passersby. Beside her is a wooden cross on a stand and a sandwich-board sign advertising the vigil: “Prayer, meditation, heartbreak, love.”

A lithe blond woman in expensive running gear passes, pushing a double-wide stroller. She sighs as she maneuvers around Wendy.

“Peace be with you,” Wendy says evenly.

She sees three women on their way to Snappy Pattys.

“God bless you guys,” she says. “Want to come in and light a candle before you have dinner?”

“No, thank you,” they murmur as one.

A woman in roomy linen clothes gets out of her car. She snaps a photo of Wendy with her smartphone and marches over.

“Why is there a cross on the sidewalk?” she says, jutting her chin.

“Well, we’re a church, and today is Good Friday.”

“The sidewalk is public ground,” she says. “That’s a religious symbol.”

Steadying her voice, Wendy assures the woman she will check to see whether she needs a permit for the cross.

“I would appreciate that.”

Wendy takes a deep breath as the woman stalks away.

“That pretty much pushes me over the edge for the time being.”

The congregation does not attempt to celebrate Easter in the storefront. Instead, they join North Prospect Union.

The humble, Craftsman-style church is nothing like their old one. Its sanctuary, with its polished wood and clear glass, might have been built by Shakers. Its small congregation is a blend of three churches that have merged since the mid-1980s.

Sanctuary hosts a breakfast in North Prospect’s cheery basement before the service. To some of the West Medford congregants, being there is like spending Easter with a distant relative: They are welcome, but it isn’t home. Yet many feel relieved to be in an old-fashioned church again.

Wendy has made fruit salad and French toast casserole for the breakfast. She greets people coming into the church.

She feels lonely. And worried. And jealous.

“I’m afraid that we’re going to fail,” she says.

Across town, Kim drives with her daughter’s family to the Trinitarian Congregational Church in Concord, a white-steepled church straight out of Yankee Magazine.

It is packed. Her granddaughter patters agreeably into the nursery, filled with children playing.

In the church sanctuary, Kim counts silently: 28 pews, about 20 people in each. Plus the balcony. Plus the sunrise service, plus the 11 a.m.

Everyone said the collapse in West Medford was happening everywhere. That’s clearly not true.

Gospel readings, a rousing sermon, a high school trumpet player, “Jesus Christ is Risen Today.”

Maybe the church consultants were all wrong, she thinks. Maybe the old church had died because it had slowly drifted away from — this.

“It only took us 18 minutes to get here,” her son-in-law says.

Paul Roberts, Sanctuary’s co-moderator, is standing on an observation deck at Plum Island.

A few days here each spring, migrating raptors — kestrels, merlins, harriers — fly low, their plumage set off to astonishing effect by the reflected light off sea and sky. But the weather is mercurial, the flights impossible to predict. The only way to see them is to keep showing up.

On this warm May morning, the sky is empty but for some herring gulls. But to Paul, the perseverance it takes to see the passing birds each spring is a small price for a few hours of transcendence. And so it is with church.

On a flight home from Chicago two years ago, Julie, his wife, appeared to suffer a stroke. She became incoherent, she kept folding and unfolding her boarding pass. It turned out to be toxic shock syndrome from a ruptured gallbladder. For a few days before she got better, Paul had to confront the terrible specter of life without her.

When he came home to shower and sleep, he found dinner waiting. Church people. Utterly ordinary, but to Paul, in that moment, miraculous.

What Sanctuary was trying to do was worthwhile, he thought. What it required was patience. And a will to look outward, beyond their familiar world, to see what other people in Medford needed.

Wendy feels lighter, buoyed by the warmth of spring.

The storefront feels busier. Midweek chair yoga is packed. There are gallery talks about faith and art featuring the work of local artists, coffeehouses showcasing local musicians. A Faith and Film group watches “Gravity” on a big screen in the storefront and plunges into a bracing discussion.

Wendy hires musicians for Sunday worship, a dramatic improvement; she tosses out her sermons and leads a conversation instead. One Sunday in May, she brings in an armload of forsythia and asks everyone to speak about pruning: What do they need to cut out of their lives to generate new growth? The talks are intimate and sometimes exhilarating; other times, hardly anyone shows up.

Wendy is trying to bring in new people, but it’s slow going. She baptizes the infant daughter of a couple from Medford, but the family returns only a few times after the ceremony.

Nobody signs up for Called to Care, the volunteer hub for practical help and spiritual support that Wendy imagined as a centerpiece of Sanctuary.

But the congregation remains devoted to its mission work for the Lakota Sioux Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, raffling a Lakota quilt and selling cookies to benefit the reservation.

Much of Sanctuary’s most urgent ministry happens during the day, when people wander in, looking for a pastor. One afternoon in late spring, a woman in her 60s arrives, wearing bright colors and a pillbox hat. Wendy tells her about Sanctuary over coffee.

“I could really use a prayer.”

She is desperately trying to stop smoking. Drinking, drugs — everything else she has quit. But she just can’t seem to let go of cigarettes.

Wendy grasps the woman’s hands. She prays aloud with her. For a moment, everything else fades.

“Amen.”

A thousand miles away, a white supremacist walks into Bible study at Charleston’s historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church and shoots nine African-American congregants to death.

Wendy is at the parsonage in Medford, about to sleep, when she sees the news stories on Facebook. Weeping, she sits up in bed, turns on the television.

Her boys are all she can think of: Aaron, her loving, empathetic 15-year-old; Alex, her musical, brainy 20-year-old. What horrors might await her biracial sons in this racist world? She could not protect them. As a white person, she feels somehow responsible, and compelled to help make change.

What can she do?

One of her hopes in coming to West Medford was that her congregation could become the rare faith community that is home to people of all colors and where interracial friendship feels normal. Since the Ferguson, Mo., shooting, she has attended peaceful marches and put Black Lives Matter signs in Sanctuary’s windows, but getting Sanctuary up and running has consumed most of her energy.

Now, Charleston catapults her into action.

She joins with other clergy in town in leading a vigil with the local NAACP at the West Medford Baptist Church.

Sanctuary hosts a discussion about race. The people who show up — all white — seem desperate to talk about their grief and confusion about what they can do. They stumble around. It is honest, raw in places.

Wendy prays the conversation “might be a starting point for our community.” It feels like it might be. But then her father dies of cancer, leaving her mired in grief. And she is distracted by Sanctuary’s efforts to hire a community minister to help the church grow. So the conversation about race has to wait.

Wendy’s approach leaves Kim feeling further alienated from her church. Her husband and son are police officers. The Black Lives Matter poster in Sanctuary’s window is, to her, an accusatory finger pointed at law enforcement families like hers.

Wendy’s post on the Sanctuary blog after Charleston solidifies Kim’s aggrievement: “I am done dear white friends,” Wendy wrote. “I’m done being nice-nice while nothing changes and the privileged say stupid shit like, ‘All lives matter.’ ”

Kim doesn’t see herself as privileged. She does not think her family is racist, either. She lives with the fact that the men she loves most could go to work and not come home.

Paul, who has e-mailed Kim many times hoping she will return, urges Kim and Wendy to talk. They never do.

Wendy feels that if Sanctuary is to survive, she must turn her attention outward, beyond the old congregation, to the larger community. She is involved in Medford now; she knows the arts people in town, the politicians, the health care people, the clergy.

She is becoming, she hopes, a kind of chaplain to the community.

A woman with short, purple-streaked hair drives a small pickup truck along High Street. It’s a Sunday morning, early November 2015. She makes a couple of passes between an old stone church on one side of the commuter rail tracks and a white-steepled Catholic church on the other.

Confused, she checks the address again. At last, she pulls to a stop in West Medford Square. The sign over the door of the shop confirms it: “Sanctuary United Church of Christ.”

She sinks back into her seat. A storefront church. The website hadn’t given any hint. Can she force herself to go in?

Joanna Begin needs a church. That much she knows.

She had been attending a Southern Baptist church for eight years. Between Bible study and volunteering, she was often at church-related events three times a week. She had wandered into that congregation unaware of its ideological leanings. She fell in love with the people, the mission work.

Then, at age 33, the high school math teacher discovered she was pregnant. Her boyfriend was living in California. They decided he would move in with her, and they would try raising their daughter together.

Her church could not accept it: She was not only refusing to repent for having sex out of wedlock but flaunting her lack of remorse by moving in with her boyfriend. Eventually, she was excommunicated. People she considered good friends evaporated.

She senses that if she doesn’t find another church soon, she might never go back.

She stares at Sanctuary’s storefront window. She has been looking for a nice, reliable, middle-of-the-road church. Boring. Boring would be fine.

She steels herself, gets out of the truck. She opens the door and hesitates. People are moving chairs around. Is she early? Late?

Everyone is old.

A tall man with a warm affect — Paul Roberts — welcomes her. He is wearing the same sort of plaid shirt her grandfather always wore. She decides she can survive the next hour.

As the service begins, she scans the room. There are paintings on the walls — a series of fruits and vegetables, moody portraits of families. What are they doing there? She takes an instant liking to the pastor — Wendy’s informality, her offhanded emotionality remind Joanna of a close friend.

She is moved by the way people in this church pray out loud, extemporaneously, from the heart. They seem so close. It is like worshipping in someone’s living room.

After the service, she falls into a conversation with longtime members of the congregation, and finds herself spilling out her whole sad story. And they tell her theirs.

When she gets home, her boyfriend looks up.

“So it was good?”

She feels herself smiling.

“I think I’m going to go back.”

Joanna cannot see, on that first visit, the congregation’s brewing discontent.

Wendy is overworked and exhausted, still grieving her father. She’s in constant pain as she prepares to take a six-week leave for hip replacement surgery. And some of the congregants are resisting her ideas.

Kathy Williams, an influential voice, worries Sanctuary is in danger of becoming an arts organization with a vaguely spiritual patina. She still has confidence in Wendy, but one member of the leadership circle, Karen Barca, does not. Karen has clashed with Wendy since shortly after her arrival. Wendy sees Karen as “a classic antagonist in the church” — and some of the others agree.

Karen, a social worker who joined the church in 2009, considers herself a check on pastoral authority, giving voice to those who are reluctant to speak up.

So it was that she found herself one Sunday morning in February 2014 tangling with Wendy over the Communion bread. A few months earlier, Wendy, who was trying to avoid gluten, decided the church should go gluten-free. A congregant’s loaves came out too crumbly, so Wendy quietly baked her own version; it was, to some, inedible.

Karen, who was in charge of setting up for Communion, came to Wendy’s office to show her a plate with a kind of Communion buffet, a choice of white bread, whole wheat pita, or gluten-free bread.

She vividly related her disgust with the gluten-free loaf. Wendy snapped. “Give me the [expletive] bread!” and hurled the loaf in the trash.

Wendy, mortified, hastily apologized, but their relationship remained strained.

Since the congregation moved, Karen has raised a host of concerns about Sanctuary’s offerings. She sometimes has a point: After Wendy worked with neighboring businesses to throw a Halloween block party that drew nearly 1,000 neighbors, Karen questioned what Sanctuary had to offer the children who came in droves. The truth was, not much.

But her needling makes it hard for Wendy and others in the Leadership Circle to listen to her. Karen thinks it’s time to get rid of Wendy.

They’ve been in the storefront just over a year. Kathy calls for a congregational meeting to discuss Sanctuary’s progress and plans for the future.

Wendy agrees to listen, but not speak. She feels set up: Sit there, shut up, and we’ll tell you what we’re not happy about.

Kathy isn’t happy, either. The format is not a free-flowing discussion, but rather a list of questions, with responses limited to two minutes.

They talk about what they’ve done well: incorporating communal meals and visual art into worship; provoking discussions about the intersection of faith and popular movies.

But there is a good deal of fretting: The arts events aren’t religious enough. Sometimes, it is hard to feel close to God in the storefront. There are too many events; too few help the community.

Wendy stares at the floor.

Kathy tries to say what is on her mind: They must remember, she begins, “The purpose is to build disciples, to bring people to a deeper understanding of their relationship with Jesus Christ.”

When it is over, nothing feels better, or even fully aired. Kathy wonders grimly what Joanna, on her second visit to Sanctuary, must be thinking.

Wendy looks wrecked. Her hip surgery is supposed to happen in two days, but a sudden scare about her heart requires a doctor’s attention first.

“Let me know how it goes tomorrow,” Paul tells Wendy. “We’ll be praying for you.”

This is what Joanna is thinking: That was awesome! Like going to a family wedding on the second date.

The congregation, she thinks, is asking hard questions that more established churches don’t.

In November, the United Church of Christ awards Sanctuary an $80,000 grant. The denomination sees Sanctuary as a worthwhile experiment.

But at the ground level in West Medford, the air feels dangerously unstable.

It is December now. Paul Roberts and Bruce Roberts, the co-moderators, visit Wendy at the parsonage after the church’s Christmas cookie sale.

Wendy, who is recovering from hip surgery, seems profoundly discouraged. Paul is surprised to see how fragile she looks. She draws a line: She cannot stay if Karen remains in the Leadership Circle. And the congregation needs to stick with the mission it voted for last year. She does not want to sit by the bedside of a dying congregation.

Internal strife had contributed to the congregational collapse that forced the sale of the old church. Sanctuary is too small to survive another exodus. They need to pull together, Paul thinks, and focus on the most important questions: Who are Sanctuary’s neighbors, and what do they need?

Amid all the frustration at church lately, Paul has been thinking about his parents, both gone a long time now.

His dad, the Rev. Norman Roberts, was a tall, balding man with a booming voice who hunted and fished with his congregants and gave a children’s sermon every week. Paul’s mother, Grace, led the women’s groups at church; in another era, she might have been a minister, too. They lived their faith. They were tolerant and loving of those who were not.

Their churches sometimes writhed with conflict. But they believed in church as a way of being in the world.

On New Year’s Eve, Wendy lets herself into Sanctuary’s back door. She is alone in the storefront, hoping to catch up on work.

The time off has helped her rest. She has cleared her head and gotten some of her energy back.

The glimmers of success in Sanctuary’s first year flicker in her mind. People know her around town. They like her. She has been invited to pray at the incoming mayor’s inauguration.

As she settles down to her desktop, she finds a pair of sticky notes. One is a little affirmation she had stuck to her bookshelf months before: “Being a pastor is not being a punching bag.”

The other is signed with Karen’s initials: “Being a pastor is not being a bully.”

Paul is walking to the annual congregational meeting. He has no idea what is about to happen.

As he walks, Paul sees a woman struggling down the sidewalk with her walker. She has been coming to Sanctuary since the fall. They greet one another warmly. Her effort humbles him, makes him forget his anxiety for a moment.

The tiny storefront is as packed as it’s ever been. Paul surveys the mix of old faces and new ones. Three people are joining Sanctuary this morning, including Joanna. They will have 27 voting members present, plus several more who are thinking about it.

When Kathy makes a motion to reject a $1,250 grant from the Medford Arts Council on the grounds that it could stifle the church’s ability to freely preach Christianity, Joanna, who joined the church minutes earlier, raises her hand.

She says it is possible to share your faith without squelching someone else’s.

“The reason I became a member today is because I was part of a black and white church, where it was either yes or no,” Joanna says. “And I love the gray that you guys have.”

The voices of the new people enliven the room. Longtime members seem suddenly revived.

Wendy doesn’t say much: For once, the congregation seems to be handling things.

“I love you all,” Kathy says at last, withdrawing her motion. “I have accomplished my goal, which is to stir you up for Jesus. . . . We cannot be a bunch of milquetoast believers.”

Despite opposition from Karen — and Kim Grubb, who calls into the meeting on her cellphone — the budget passes and the congregation extends Wendy’s contract for two years.

Karen resigns from the congregation two days later. But Kim cannot bear to transfer her membership to another church.

She will bide her time, read Sanctuary’s newsletter, monitor the posts on Facebook. West Medford is home. Ministers come and go.

On Easter morning, their second since leaving their grand old church behind, they gather in darkness beside the Mystic River.

Joining the handful of people from Sanctuary are people from three neighboring churches, including Shiloh Baptist Church, a once-mighty African-American congregation in West Medford. Back when it was bigger and stronger, Shiloh used to hold an Easter sunrise service along the Mystic.

Sanctuary has hired a community minister at last. The Rev. Lambert N. Rahming Jr., a young African Methodist Episcopal minister just out of seminary at Boston University, stands alongside Wendy as she tells the story of Jesus’ resurrection.

Birds chitter high overhead. Paul and his wife, Julie, can hear robins, a blue jay, a cardinal, somewhere out of sight.

They sing “In the Garden,” one of June Livingston’s favorite hymns. But Kim isn’t there.

She had planned to go to church in Concord again this year, but her infant grandson is sick, so she stays close to home in case her daughter needs help. Later on Easter morning, she thinks of going to Sanctuary, but, driving by, finds the storefront dark. She goes to sit by June’s grave for a while.

At dawn, along the river, night sky fades to low gray clouds. The air is raw. Sanctuary’s youngest members, three teenaged boys, carry torches. It is as though everyone is huddled around them, sustained for the moment by their light.

Produced by Russell Goldenberg, Elaina Natario, Laura Amico, and Lloyd Young