Teaching a driverless car to turn left

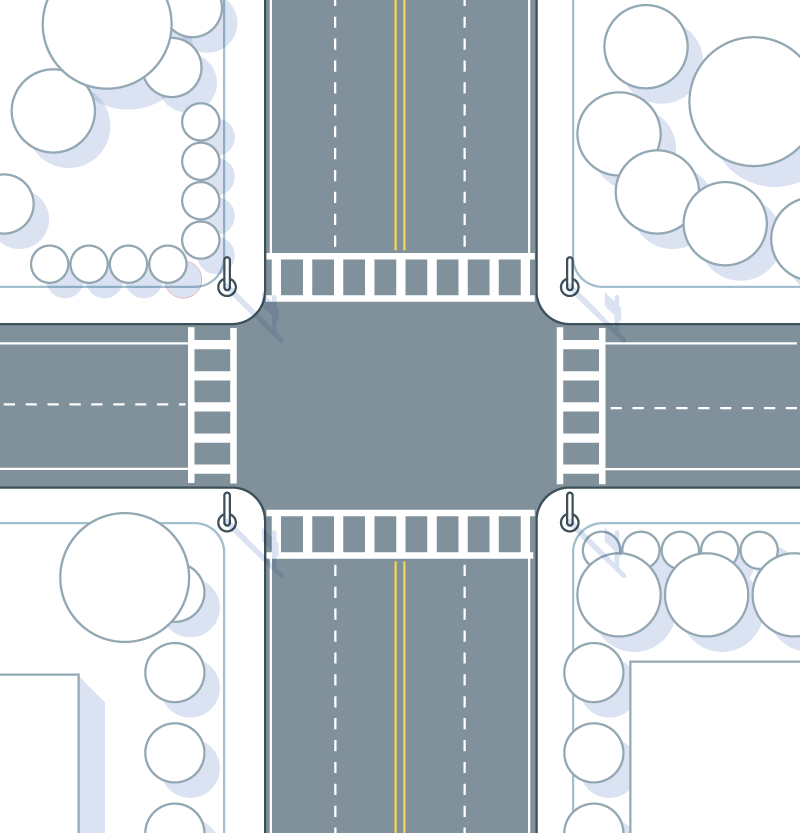

In a perfect world, cars and trucks would never turn left. Left turns waste time, gas, and are dangerous for drivers, oncoming traffic, and crossing pedestrians. So imagine teaching a machine to turn left — in Boston's infamous traffic, no less? A driverless car has to read human psychology — the subtle signals from other drivers and pedestrians — to navigate one of the hardest maneuvers on the road.

As engineers race to build self-driving cars, they’ve found that making them safely turn left is one of their toughest problems. “I see a lot of challenges every day, and left turns are near the top of the list,” said John Leonard, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who specializes in self-driving vehicles.

Left turns are so tough because they involve psychology as well as technology. Drivers and pedestrians read subtle signals from each other as they approach an intersection. We’ve come to learn how to read those signals to make pretty good guesses about when it is safe to turn left in a variety of traffic conditions.

“Human beings are remarkably good at that because we’re social beings,” said Gill Pratt, chief executive of the Toyota Research Institute, an organization founded by Japanese carmaker Toyota Corp. to solve critical problems in automotive and robotic technology.

AdvertisementContinue reading below

But today’s automated cars don’t know how to read people — and people don’t know how to read them. As a result, said Pratt, building cars that can safely negotiate all kinds of left turns will take years — perhaps more than a decade.

Turning right at an intersection is easy. You just steer into the right-hand lane of the intersecting road. It’s so simple that, at many intersections, drivers are allowed to turn right even when the traffic light is red.

”

31: The percentage of accidents with claims of at least $100,000 at Arbella Insurance in 2013 involving left turning vehicles

A host of complications may arise. Traffic may be backed up in the lane that the driver wants to enter. Should he begin the turn and hope a space opens up, or wait till he’s sure he’ll get in? Is there a car in the opposite, oncoming lane? How far away is it? How fast is it moving? Can he complete the turn in time? Are there pedestrians crossing into the path of the car’s turn?

People manage this complex process millions of times every day, but all too often, we get it wrong. A 2010 US Department of Transportation study of over 2 million US car crashes found that vehicles making bad left turns caused 22.2 percent of the accidents, compared to just 1.2 percent caused by right turns.

AdvertisementContinue reading below

“Basically, a left turn is the most complex thing we humans do in the complex world of driving,” said Tom Vanderbilt, author of the bestselling book, “Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do.”

“What makes this particularly hard — particularly as we get older — is that we are not very good at judging the speed and distance of objects coming from straight ahead,” said Vanderbilt. “We only begin to exactly discern the speed and distance of the approaching car when it’s very close to us, which is often too late.”

For an automated car, judging speed and distance is the easy part. Adorned with GPS navigation gear, video cameras, 3-D laser rangefinders and radars, these vehicles can precisely measure the relative speed and location of everything in its path. What they can’t do is reliably predict what those cars and pedestrians are going to do next.

Even so, the sensors aren’t perfect. Consider what happened in March in Tempe, Arizona, where Uber has been testing one of its self-driving cars. An Uber car was passing straight through an intersection when it was hit by a human-driven car turning left. The human didn’t see the Uber car. But the self-driving vehicle’s sensors also failed to spot the human driver.

In a more tragic case from Florida last year, a Tesla electric car running in semi-autonomous mode plowed into the side of a tractor-trailer that made a left turn into the car’s path. The car’s sensors should have applied the brakes. But according to Tesla, the car failed to spot the white-painted side of the truck against a background of bright, sunny sky.

But even when sensors perform perfectly, self-driving cars can’t reliably predict what human-operated cars and pedestrians are going to do next.

Scientists call it “theory of mind.” It’s the human knack for guessing what other humans are going to do based on subtle hints like tone of voice, body movements, even the look in someone’s eye. Theory of mind is why people instinctively get out of each other’s way in a crowded subway station or at a baseball game.

Theory of mind also kicks in whenever drivers and pedestrians approach a busy intersection. Instantly and sometimes unconsciously, people begin exchanging visual clues that reveal whether it’s safe to proceed. “Some of the information is transmitted with incredible subtlety,” said Pratt.

”

108: The number of deaths among pedestrians and bicyclists in New York City between 2010 and 2014 involving left turning vehicles

But today’s self-driving cars aren’t nearly this smart. They can’t recognize the body language or glances that would tell them that an oncoming car is slowing to make room or that a crossing pedestrian plans to keep on going.

The self-driving cars won’t slam into oncoming traffic or drive right over pedestrians. When one of them can’t decide what to do, it will simply stop. But that could lead to traffic jams at busy intersections. It could also cause accidents, as frustrated human drivers try to cut around a hesitant autonomous car, only to plow into oncoming traffic.

And the theory of mind problem cuts both ways. Humans also can’t understand what a robot car is “thinking.” If a pedestrian makes a last-second dash through the crosswalk, will a turning car keep turning, or will it pause? With no driver behind the wheel to nod his head or wave his hand, how will anyone know?

Pratt said carmakers will have to develop additional signaling systems to indicate a self-driving car’s next move. Future drivers and pedestrians will have to be trained to recognize these signals in much the same way we teach children about traffic lights and stop signs.

Left turns will get easier when our cars start talking to each other. Vehicle-to-vehicle radio systems, similar to the transponders found in commercial aircraft, will communicate with other nearby cars, whether automated or driven by people, so each vehicle will know what the others are doing. Late last year, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration proposed a new rule that would require all cars to have these systems in about five years.

Self-driving cars may also adopt a tactic made famous by package delivery giant UPS, which routes its 110,000 vehicles to avoid left turns wherever possible. Fewer left turns mean fewer accidents and less waiting at intersections for traffic to clear. The trucks burn less fuel and can make more deliveries per shift. Self-driving cars could save themselves a lot of trouble by using the same strategy.

Pratt predicted the industry would develop self-driving cars capable of handling most driving situations. But such cars are five to 10 years away. And Pratt said that even such a vehicle would probably require human assistance for a complex task like turning left in downtown rush hour traffic. So a car that could flawlessly make all kinds of left turns is a long way off.

“Some driving is really hard,” said Pratt, “and the hardest of those hard cases involves predicting what other human beings are thinking.”